In “A WAY OF LIFE,” Elaine Cameron-Weir’s solo show staged earlier this year at Lisson in New York, the artist presented a series of sculptures centered around The Book of Revelation. While the aesthetics evoked the apocalyptic aura of the very subject matter it addressed — the New Testament’s closing script, infamously redolent of death and end-times — the exhibition didn’t claim nor suggest we have arrived at such a scenario. Rather, the sculptures-cum-installation questioned how human beings have long sought to ingest our circumstances in times of chaos, often turning to comforting narratives despite their spurious validity. This thinking is evident in the artist’s emphasis on the concept of the theater of history, which frames history not as a strictly factual or objective record, but instead as a story produced in response to our need to understand change as it unfolds before us.

Approached from this angle, The Book of Revelation is stripped of its power. Contemporary scholars, including Princeton professor of religion Elaine Pagels in her 2013 book Revelations, have indeed argued that the mystic John of Patmos penned his text as an anti-Christian screed and fantastical metaphor for events occurring in his day. Given the centuries’ worth of handwringing it has since inspired, one might accurately call The Book of Revelation the most successful urban legend of all time – a propaganda-infused horror story co-opted by the church to instill fear and control under the guise of divine prophecy. Thus, works such as Cameron-Weir’s pupil of couture / 4horsemen hairshirt (SS 2024 apocalypse collection) (2023), made from military surplus–sourced leather trench coats, stainless steel, dyed calf leather, and studs, point to the same phenomenon at play today, underscoring the enduring power of rhetoric born from dubious origin and intention.

In looking at The Book of Revelation as a contorted tale of history later adapted by religious institutions to exercise power, “A WAY OF LIFE” continues the artist’s ongoing concern with the ways in which larger power structures dictate our perception of the world, and, by extension, warp our understanding of ourselves. The particular systems include organized religion, scientific or other purportedly “objective” inquiry, and propaganda; these coalesce in shaping the concept of identity, an arguably shoddy schema and flimsy framework for defining the self.

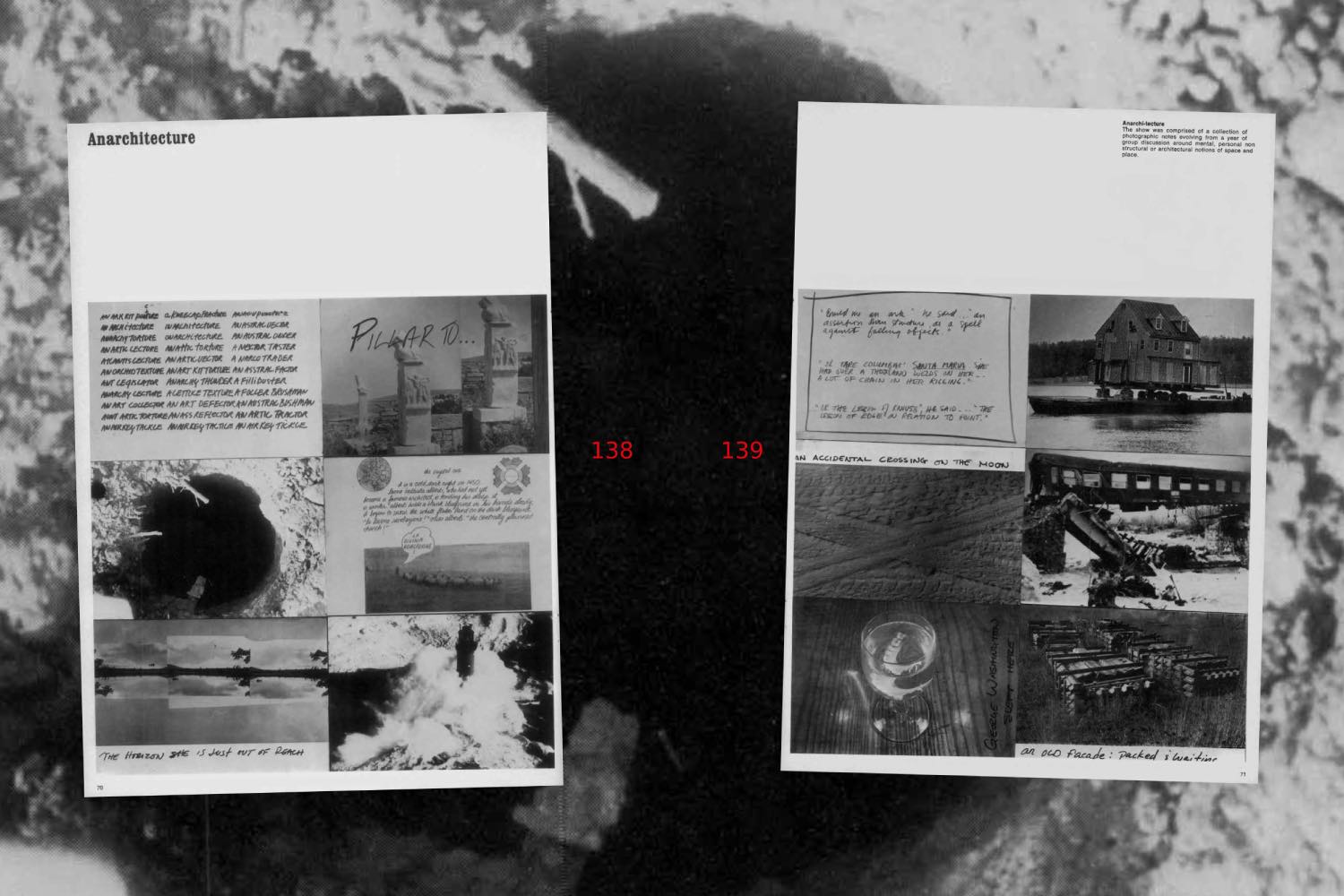

Cameron-Weir earned her MFA in studio art from New York University in 2010, where she first developed the seed of this interest during research on Walter Benjamin and, more specifically, his unfinished work The Arcades Project (1982), a vast collection of written ruminations on modern life as experienced in Parisian city life. In her 2018 paper “Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices,” professor and archivist Catherine Russell summarized the German theorist’s goal with his extensive undertaking begun in 1927: “Benjamin describes his method in The Arcades Project as one of ‘carrying the principle of montage into history… to grasp the construction of history as such.’” This conceptual objective is overtly apparent in Cameron-Weir’s exhibition at Lisson, drawing a clear delineation between her foundational focus on Benjamin’s project and resulting grasp of history as an account of events rendered pseudo-fictional by the messy human hand.

Her work can perhaps be read as an indictment of how willingly we consume arbitrary dictums in order to provide our lives with definition and meaning. (At the same time, like any good artist, she shies away from inculcating herself in the work, saying, “I think I’m just really trying to be a conduit for what I’m seeing.”) We are eager to accept that which we are handed from on high, ranging from more generalized religious decrees, scientific assertions, and historical recounts to individualized labels we voluntarily self-adhere to our own personhood. Identity, too, becomes another enforced idea — even if the identity in question exists in supposed “opposition” to the mainstream — whereby various types, contrived as they are under social structures, operate as a means of control by way of categorization.

For instance, her participation in Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale, “The Milk of Dreams,” featured Low Relief Icon (Figure 1) and Low Relief Icon (Figure 2) (2021), a sculpture composed of factory conveyor belts balanced with metal caskets, in a set-up reminiscent of the scales of justice. The caskets, which sit on an exposed metal sub floor masking electrical cables, are those utilized by the US military to transport corpses of the deceased; these are paired with cast reliefs of the crucifix affixed on the conveyor belts, as if pumped out on the factory line. The reliefs are cast copies of “spin molds,” rubber discs used in production to make cheap trinkets and jewelry from lead and pewter. Here, wearable religious iconography and the identity of the soldier are a canned product, the latter being an open subject to government, and treated as such. Yet in the need to belong, it is nevertheless counterintuitively embraced when the role is recast in that of a hero with agency. Death in warfare on behalf of the indifferent State becomes a bit more palatable when fed to us as a sacrificial act of glory.

Other identity subsets found in Cameron-Weir’s work — most prominently the dandy, the punk, and the outlaw cowboy — operate in similar terms: belonging to subcultures, in their separate ways, each is an ostensible rebel that does not subscribe to the mandates that otherwise regulate interactions in a community setting. In reality, these contradict the idea of the individual in that we are still aligning ourselves according to an identity, be it an in-group and an out-group.

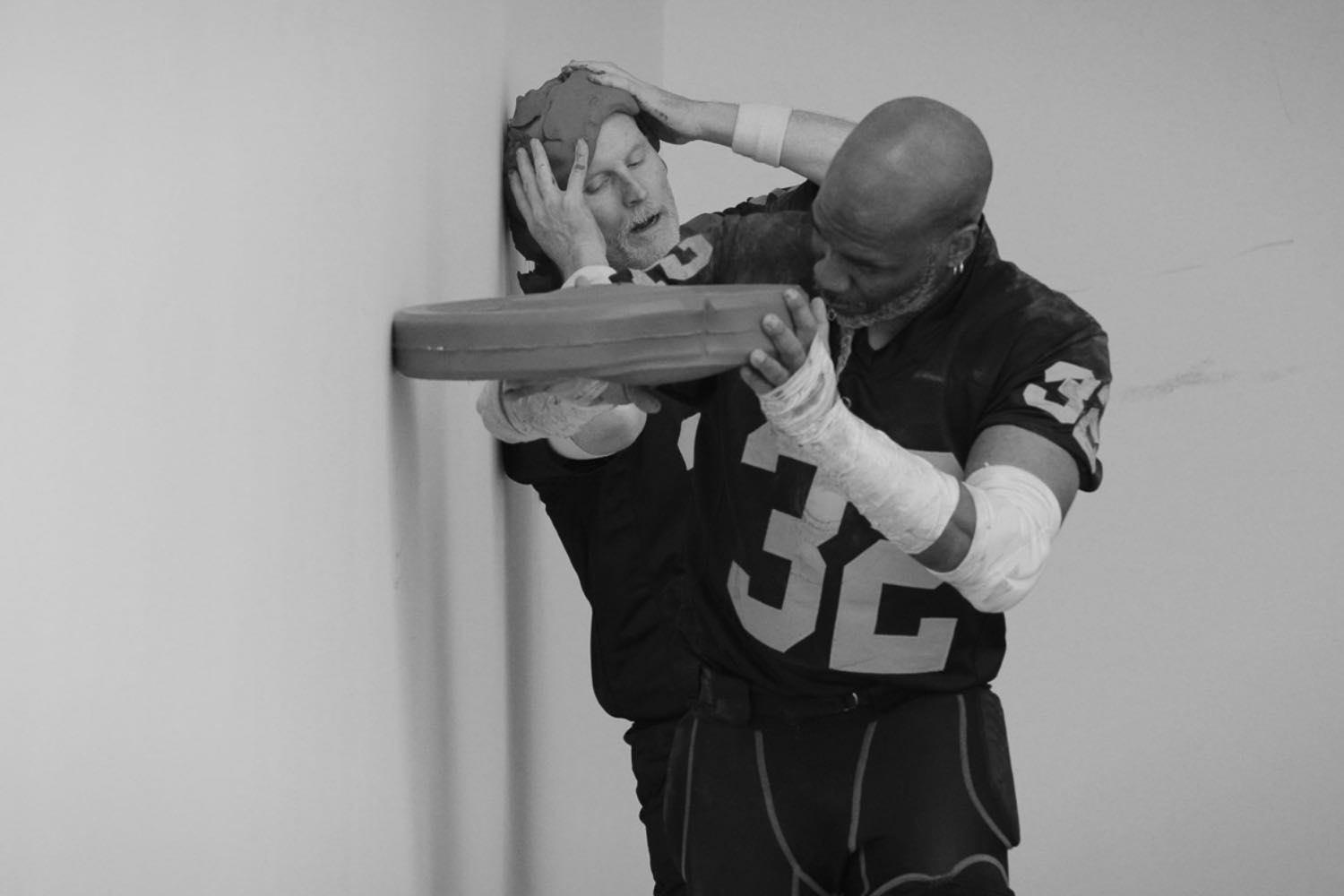

These motifs drawn from myth translate into the materials she employs. Jackets are a recurring trope throughout her work: they can be seen in the trench coats in “A WAY OF LIFE,” commenting on the items worn in trenches in World War II; in the use of horseshoes and sandbags made from hide in the same exhibition — pointing to the attire and accoutrement of cowboys; or spiked jackets first sported by punks in the 1970s. In her 2017 one-person show “viscera has questions about itself” at the New Museum, the artist installed, per the press release, “a suspended ‘jacket’ and ‘skin,’” as she often does in many presentations. With this, clothing becomes a way of adopting an identity, both making one seemingly anonymous while self-perceiving as individual by means of “style” versus a uniform.

“I mean, I guess it’s sort of related to this trend when identity is brought to an extreme through clothes,” she says. “There are these categories and echoes of a resurrected body in assuming clothing. You put on a look and consume this idea convincing you that it makes you special.”

Likewise, Cameron-Weir is interested in what she describes as “the body as a garment.” Her work around religious and scientific histories overlaps in that both hope to reconcile the body versus the soul. But, artistically, she asks what this attempt to separate a body from its soul means for our understanding of our corporeal and whole selves in defining reality. In medieval Christianity, which she takes a particular interest in, there was an urgent question around where the body goes after death and the form it takes when resurrected. The worry over a body in life, rephrased as fear over a body in death, leads to the overwhelming mystery regarding the reason for our existence at all. It is too scary to confront head-on, and so is relegated to the more easily faced pondering of the body.

This pivots into greater confusion regarding our comprehension of the body and its anatomical functioning in general: a matter of conflict unanswered by religion that scientific inquiry aimed to resolve. But like religious pontification, science is also a flawed endeavor to create meaning, control, and clear knowledge about human life: it is only paraded as fact, much like the theater of history.

Throughout her practice, it is evident that Cameron-Weir was soundly influenced by thinkers living during the advent of modernism. Alongside Walter Benjamin, she cites a tender spot for Charles Baudelaire as well as Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 book À rebours, which translates to Against the Grain. The novel’s protagonist, Jean des Esseintes, embodies the character of the dandy, who self-isolates in his disdain for nineteenth-century bourgeois society, positioning himself as a caricature of the licentious epicurean with a particular love for perfume. In her work, the artist often employs sensory elements, including scent. Further to this, at one point in the book, des Esseintes sets gemstones in the shell of tortoise, recalling Cameron-Weir’s use of clam shells outfitted in glowing lights, with aromatic frankincense candles ensconced in their beds, in her 2014 show “venus anadyomene” at Ramiken Crucible in New York.

As Albert Camus wrote in his 1951 essay “The Rebel,” “the dandy is, by occupation, always in opposition [to society]. He can only exist by defiance.” This goes back to the artist’s personal history growing up in rural Canada, where she often attended punk shows as a means of first immersing herself in a subculture: an endeavor she admits was largely futile, by her work’s own indication. This is because punk was one of the first subcultures to immediately be sold back to itself, signaling that even this pretense of a subculture fell victim to commodification. We see this in Cameron-Weir’s use of ouroboros-snake skins in her work, as in Snake 8 (2017) shown at the New Museum, denoting the reptile’s tendency to eat its own tail.

Throughout, these undertones in her work are often deemed pessimistic. That said, Cameron-Weir refutes these interpretations, and I have to agree. When speaking with her for this text, she pointedly stated that she takes issue with cynicism in art, insisting that her work in fact harbors the opposite stance: “I think there’s something in the dandy character that uses this veneer of frivolity or indulgence in the senses. That’s also, in a way, authenticity: it’s like a real time-tested method to rebel against what one is expected to do in the world. It’s almost anti-utilitarian.”

In the end, I actually consider it more optimistic to weed through these difficult topics when trying to make sense of our seemingly lost place in the world. As she says, “You have to cycle through both,” referring to both a sunny outlook in tandem with the troubling and difficult act of rebelling against circumscribed societal structures put in place to keep us blind and superficially content. “Ultimately, it is optimistic that it might not be what stereotypically you would see as optimistic,” she says. “It’s not a celebration of life.”

I laughed, comparing the alternative to the readymade “live, laugh, love” posters sold en masse at home decoration stores. She replied in consent: “Yes, this is very much like, ‘cry, scream, die.’”