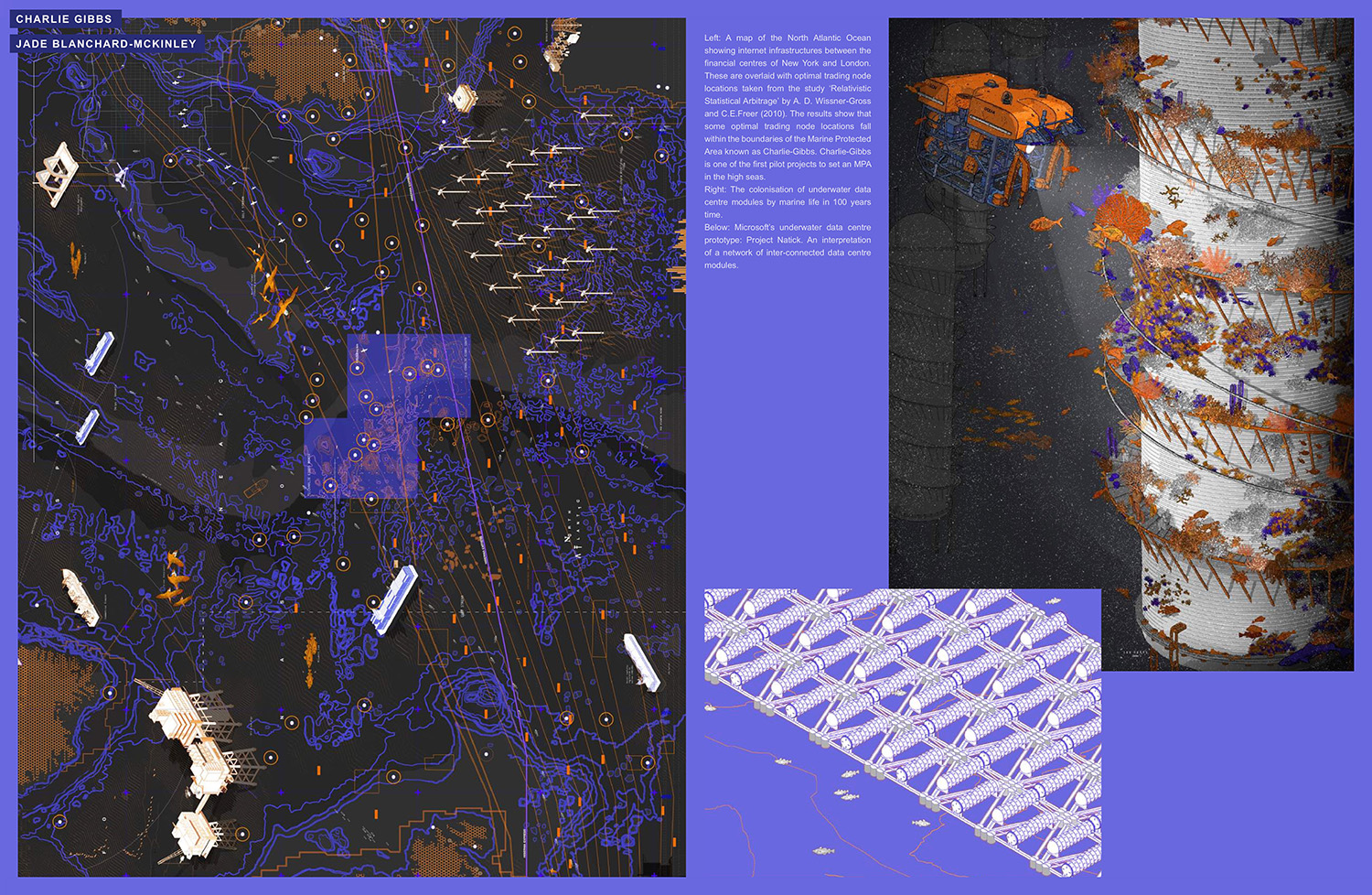

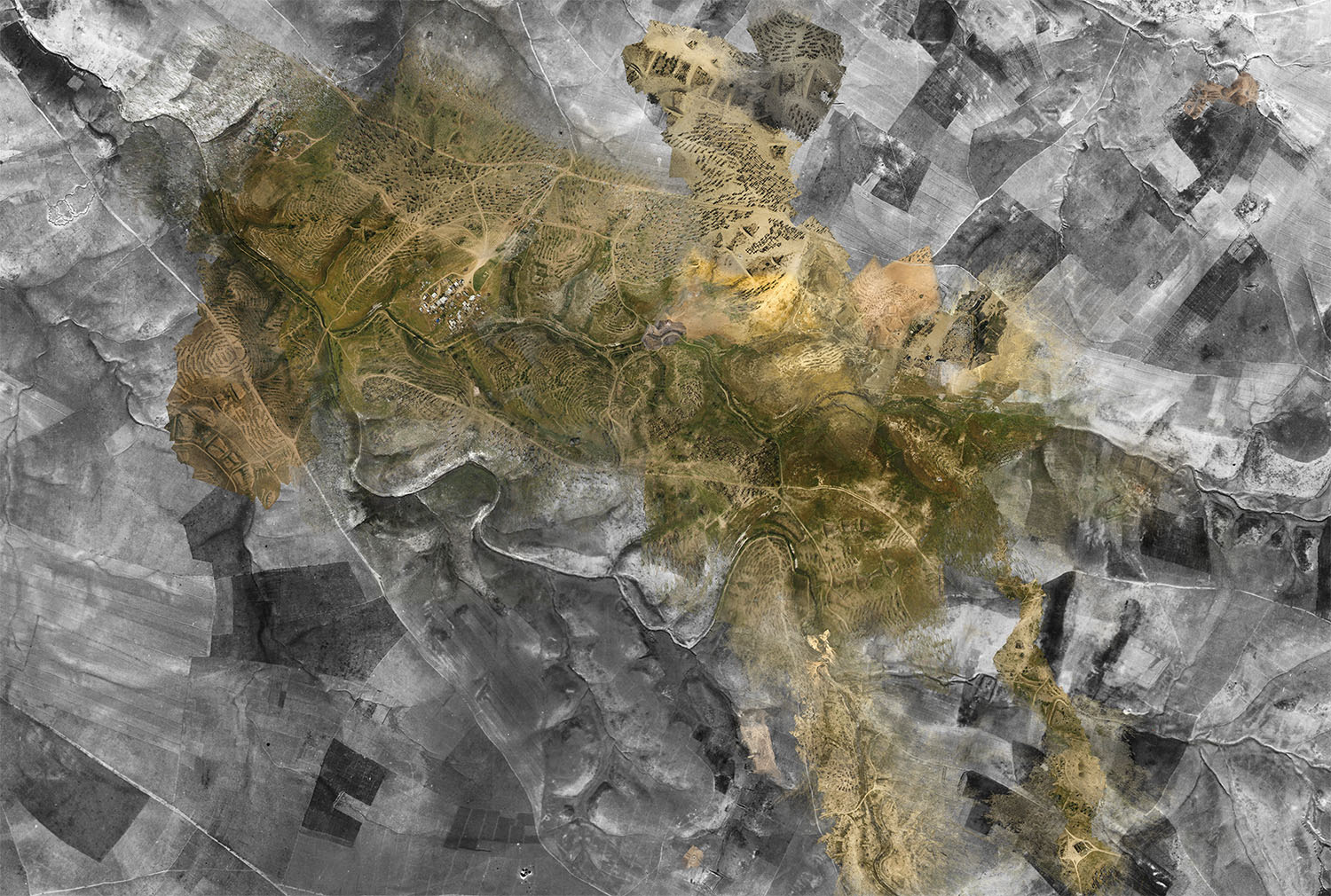

Ground Truth 1: A composite of Royal Air Force aerial photography from 1945 and ‘community satellite’ point clouds taken in 2017. Image: Ariel Caine / Forensic Architecture / Aziz al-Turi / Nuri al-Uqbi / Debby Ferber (Zochrot) / Hagit Keysar (PublicLab), 2017. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture.

The Motagua Fault is an active, moving fault that extends across Guatemala and is part of the tectonic boundary between the North American Plate and the Caribbean Plate. The confluence of geological forces which meet at this fault pull the Caribbean Plate over the North American Plate at the unsettling geologic rate of just over ten meters every one hundred years. Uplift occurs at a regional scale and is seen in the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, the highest non-volcanic mountain range in Central America. The geology is a deeply important circumstance; deposition has generated mineral-rich lowlands along the Pacific coast, and while the majority of the Cuchumatanes are covered in scrubby pine-oak forests, on the northern slopes temperate cloud forests persist. The highlands of the Cuchumatanes are home to the indigenous Ixil Maya people, who settled in three municipalities in the Quiché region. These municipalities, also known as the Ixil Triangle, are Santa Maria Nebaj, San Gaspar Chajul, and San Juan Cotzal. It is these very geological and ecological conditions that organized what historian Greg Grandin calls “the last colonial massacre”1 that saw, in the years between 1978 and 1983, thousands of the indigenous Ixil Maya people killed with around ninety villages destroyed. It is also these same geological and ecological conditions that would make the crimes of the state legible decades later.

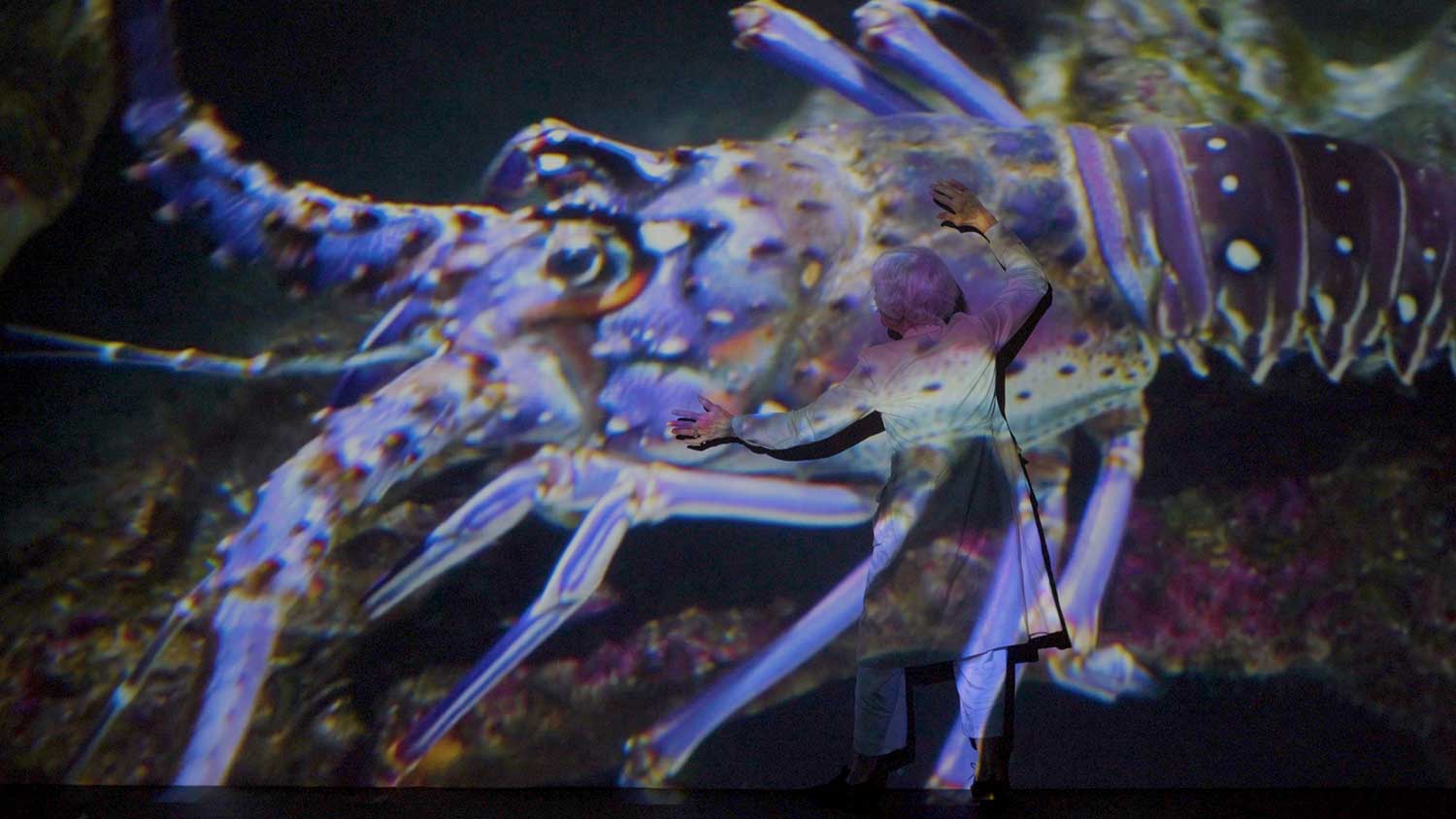

There are thirteen self-defined categories of investigation that Forensic Architecture, the research agency that investigates human rights violations, has undertaken: airstrikes, at sea, borders, chemical attacks, detention, disappearance, environmental violence, fire, forensic oceanography, heritage, land rights, migration, and police violence. In order to conduct these investigations, they have utilized fifteen methodologies: 3-D modeling, audio analysis, data mining, fluid dynamics, geolocation, ground truth, image complex, software development, pattern analysis, photogrammetry, reenactment, remote sensing, situated testimony, synchronization, and open-source intelligence (OSINT). At the time of writing, they have completed forty-three investigations.

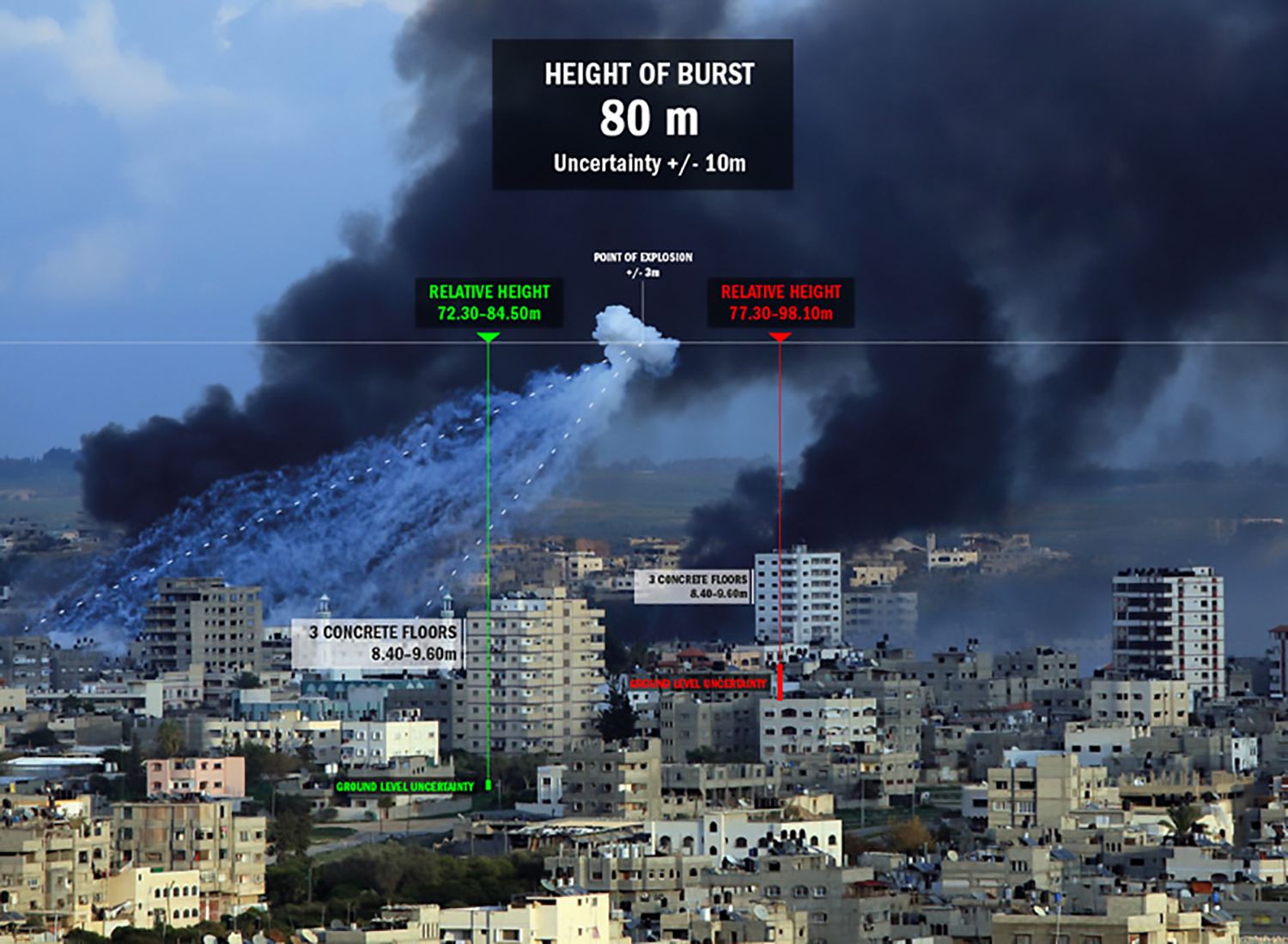

The working definition of Forensic Architecture’s “environmental violence” category is “the destruction of the natural and built environment as part of a military strategy” or the “destruction and reconfiguration of the built and natural environment and, crucially, of the relation between them.”2 If the first is an indirect form of violence that operates through the degradation of environmental conditions, including quality of land, water, air, and nutrition, by “restricting trade and access to life-sustaining infrastructure,” then the second refers to “modes of association, worship, agriculture, and economy” and is “exercised by attempting to affect the political subjectivity of native people and give rise to populations conducive to state or colonial control.”3

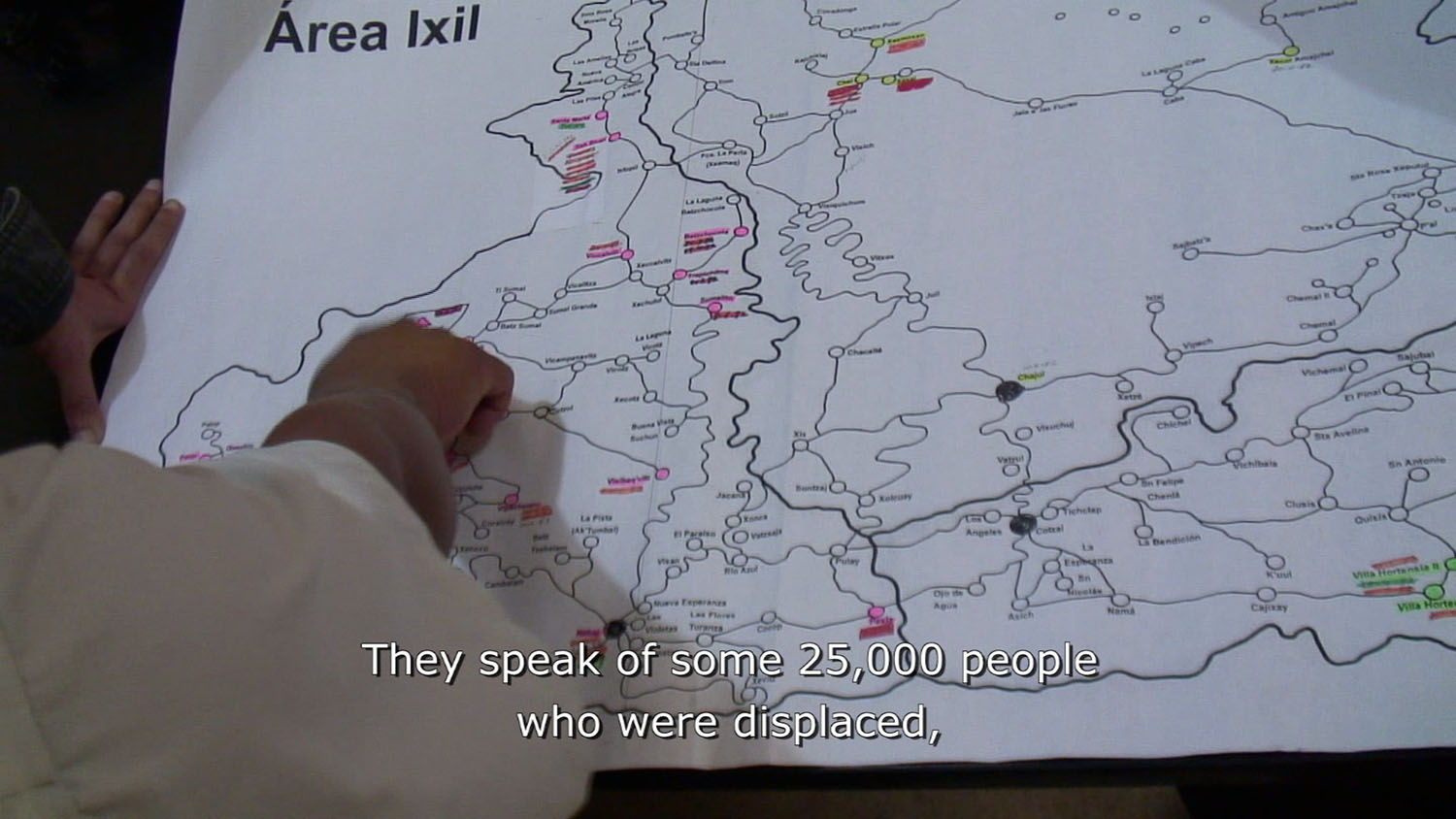

The Guatemalan Civil War began in 1960 and ended in 1996, with state security forces that included both military and military-backed civil militias acting against the Ixil Maya people. But where Grandin saw the events of Guatemala’s civil war as part of the area’s longer colonial history and the culmination of a five-hundred-year-long process of colonization, land seizure, and genocide suffered by the indigenous people of Central America, Guatemala’s Historical Clarification Commission (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico, or CEH), the body formed after the civil war to “establish the facts,” framed the violence as “acts of genocide,” an isolated incident in the country’s historical timeline. Beginning in 2011 and ending in 2013, Eyal Weizman and Paolo Tavares of Forensic Architecture conducted three periods of fieldwork, travelling from their base at Goldsmiths, University of London,4 to Guatemala. Commissioned by the Center for Human Rights Legal Action (Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos, CALDH), the goal of their investigation — the first investigation to be categorized as environmental violence, and the sixth investigation5 undertaken by Forensic Architecture — was to support already gathered evidence in the “case for genocide and crimes against humanity committed against the Ixil people in a series of trials taking place”6 in Guatemala through the production of a set of cartographies.

The indigenous Maya comprised sixty percent of the population of Guatemala yet represented over eighty percent of the victims of the civil war. Even before the civil war, over the course of generations, the Ixil Maya had fled colonization, from the coast to the mountains, and it was this path that the Forensic Architecture team followed, along with a group of forensic archaeologists and anthropologists. They began their research at 300 meters above sea level in the fertile lowlands of the Pacific coast, moving up to the pine forests and corn fields of the Central Highlands, between 1500 and 1800 meters above sea level, and finally, up to the rocky terrain of the Western Highlands at 1900 meters above sea level; during the civil war, the entire extent of territory was occupied by state military forces. Living in the highlands may have provided geographical and political separation for a time, but it was this same autonomy that would ultimately be seen as a threat to the state, by the state.

Forensic research was conducted at the scale of architecture with the search for and examination of building ruins in an effort to estimate the population and extent of villages, and at the scale of the region in an effort to understand the physical transformation of the Quiché region. Since the buildings of the Ixil tended to be constructed out of wood, once the buildings were razed or abandoned the organic nature of their remains tended to be rapidly consumed by cloud forest conditions. Local archeologists shared two key indicators to locate the remains of buildings: the first was geological, to seek out irregular cuts or smoothness in an otherwise rocky and uneven terrain. The second was flora: the presence of specific fruiting trees including avocado, papaya, or peach indicated an outdoor domesticated garden, and often the corners of a house porch. If it was suspected a building was underneath some thirty years of overgrowth, sticks would be used to probe the ground for the rock foundations, and machetes would then be used to clear the heavier plants, allowing for the measurement and surveying of former homes and villages.

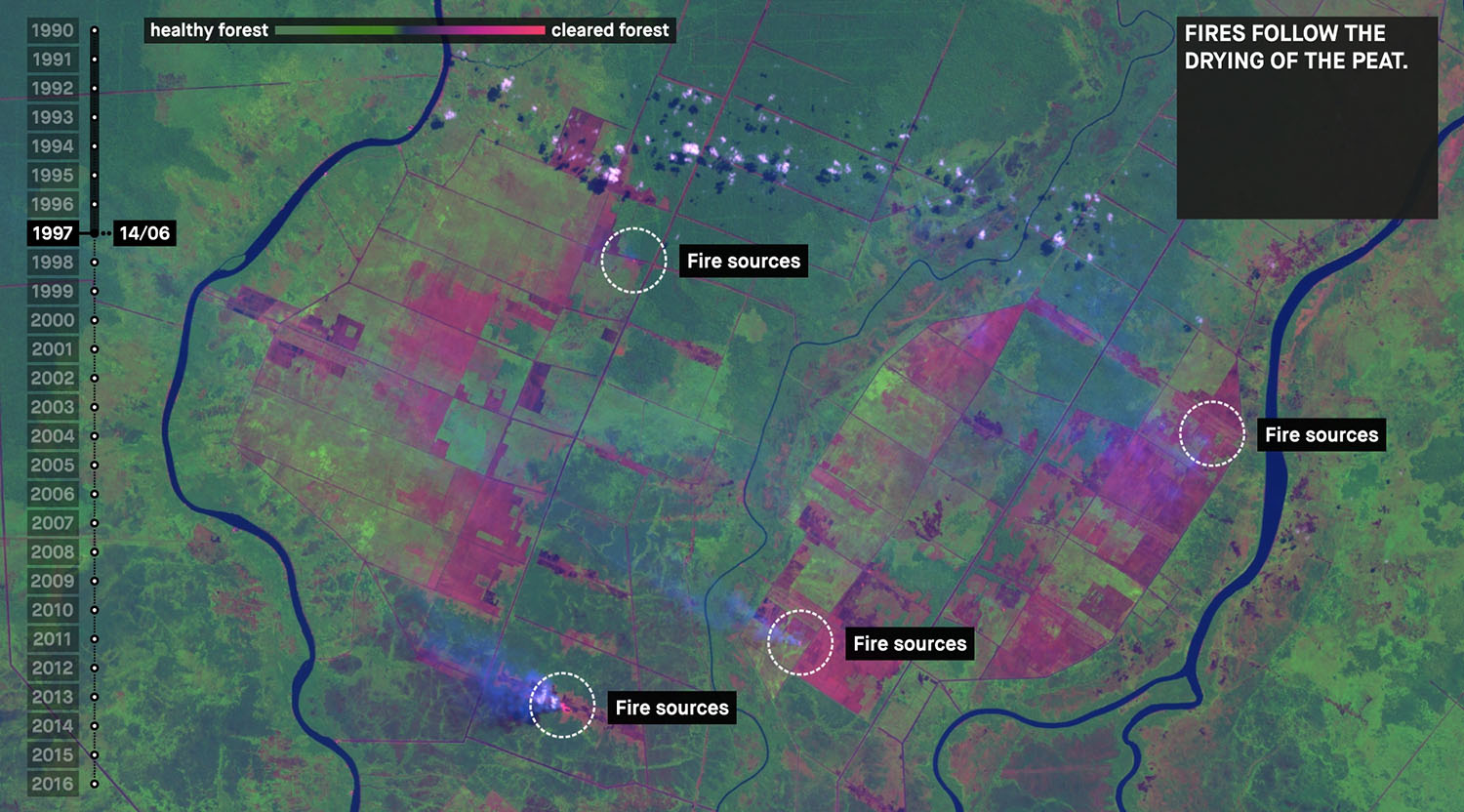

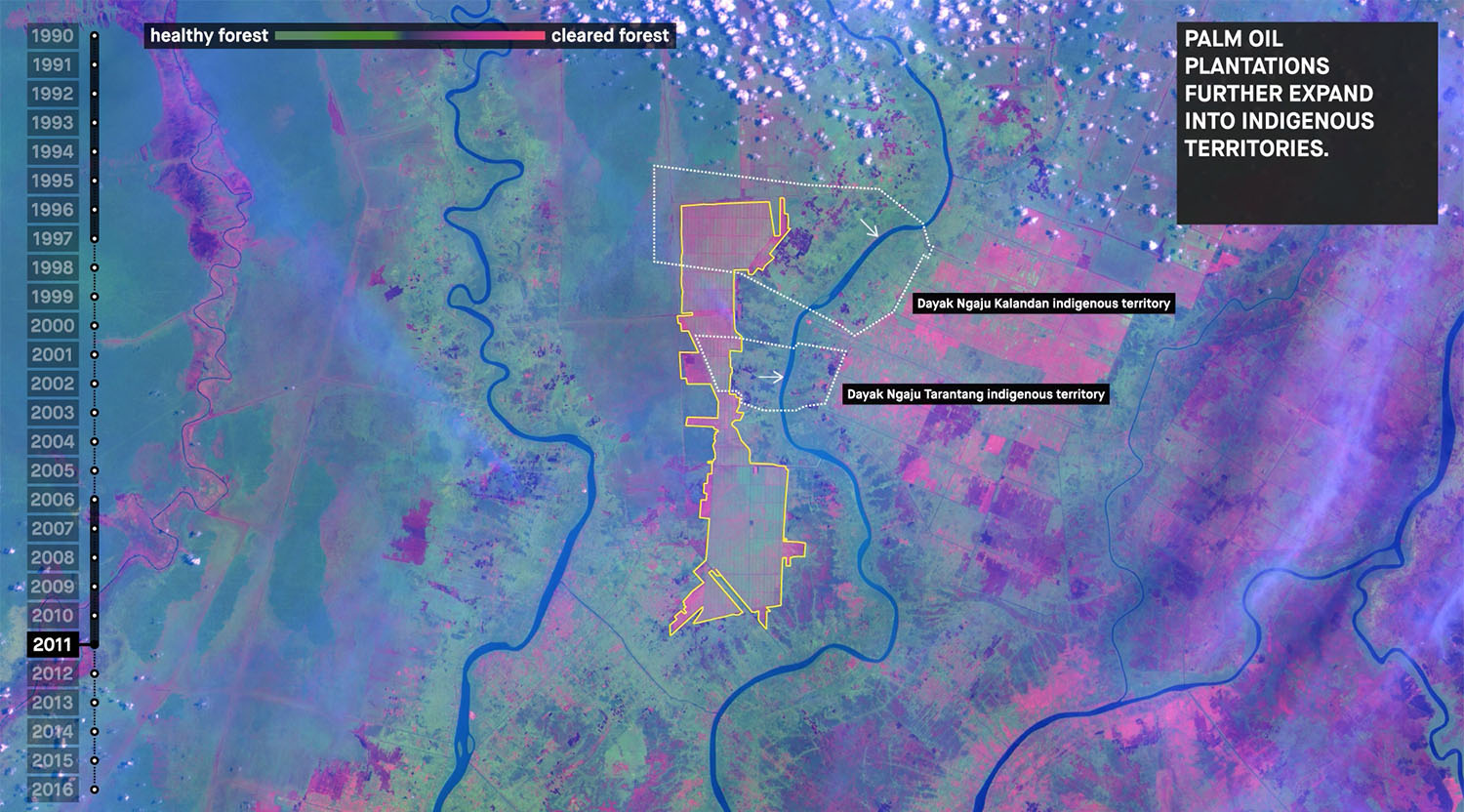

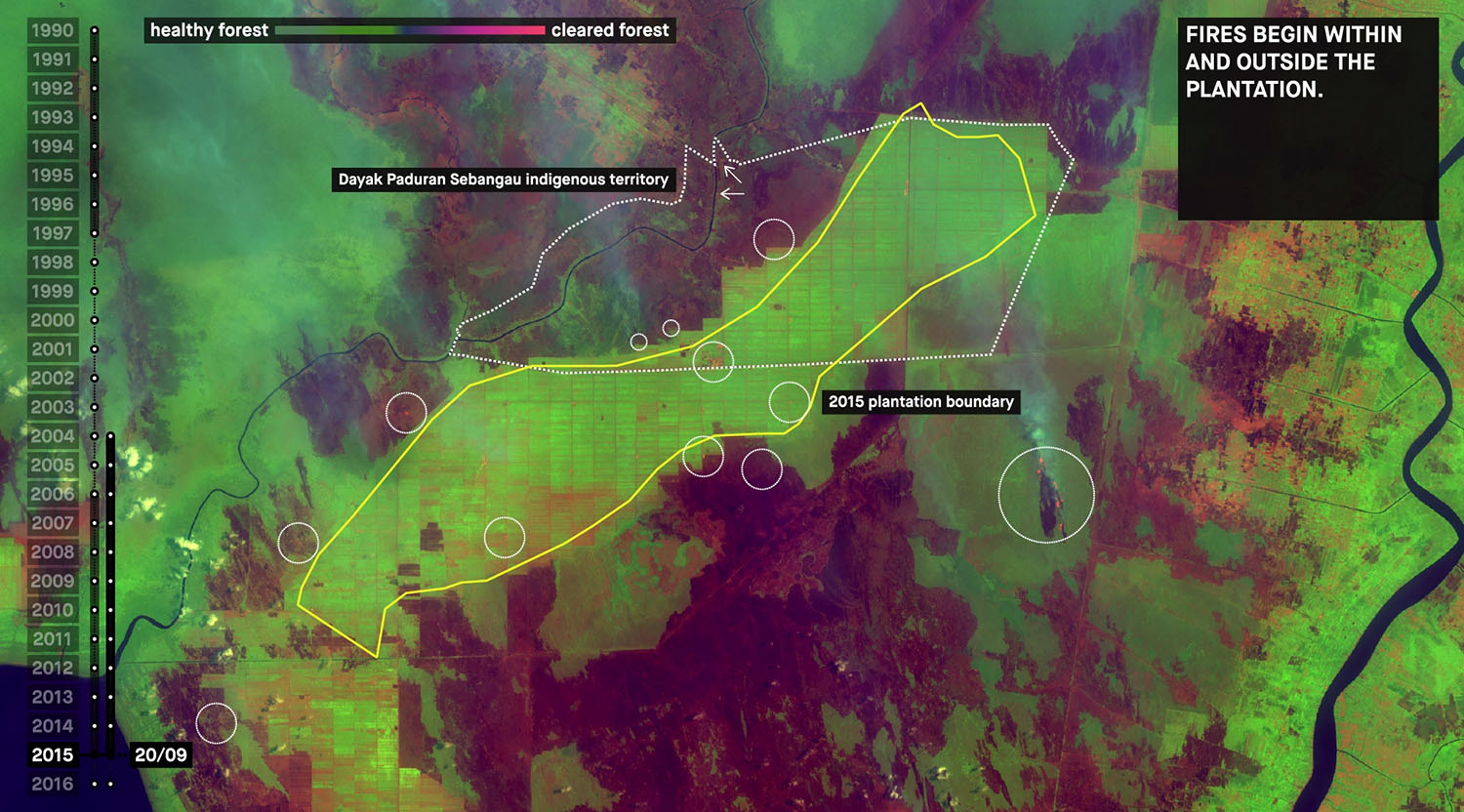

In addition, the research teams examined aerial images gathered from Guatemala’s Instituto Geografico Nacional and the US Keyhole-9 satellite. Using a combination of remote sensing, pattern analysis, and identification including the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) that assesses the photosynthetic activity of plants to analyze and identify temporal changes in land cover, the investigation compiled a cartographic data set that registered the systematic violence against the Ixil Maya people during Ríos Montt’s dictatorship. Ultimately, eighty percent of Ixil villages had been destroyed with forests and fields burned. Those who survived were resettled, first to “refugee centers” and then to militarized “model villages” where they were forcibly educated in modern agricultural techniques.

As Ross Exo Adams recently wrote, landscapes “appear at once as a consistent background against which contemporary problems obtain visibility and, increasingly, the object occupying the foreground itself.” If, as Adams goes on to suggest, the landscape is an archive and a historiographic text, it is only the process and framing of landscapes as distinct political ecologies that may serve to “deliberately outline an activism by which to achieve a certain outcome.”7 It was through Forensic Architecture’s careful and rigorous reading and documentation of these landscapes that both scales of violence — at the scale of the body and at the scale of the region — were made legible by the very matter that constitutes the landscapes under study, including the rocks, the soils, and the flora. Disruptions or interruptions in “naturally existing forces, flows and processes”8 marked precisely where the historical narrative of human culture — in this case, the violent genocidal acts against the Ixil Maya people — could be revealed. Ultimately Forensic Architecture’s research situated the events of the civil war, and in particular the dictatorship of General Efraín Ríos Montt,9 within the longer timescale of the area’s colonial history that includes the Spanish occupation, cultivation, and settlement of the region.10

According to the United Nations, genocide is the “intentional, direct, or indirect destruction of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group by systematic murderor serious physical or emotional traumaor the intentional subjection of a group to life conditions with the intent of securing their complete or partial physical destruction.”11 On May 10, 2013, General José Efraín Ríos Montt (the military dictator of Guatemala between March 1982 and August 1983) was convicted by the National Court of Guatemala of genocide and crimes against humanity, and was sentenced to eighty years imprisonment. Ten days later, the Constitutional Court of Guatemala overturned his conviction. The Ixil then took their demand for justice to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Although his retrial began January 2015, Montt died of a heart attack on April 1, 2018.

Landscapes are spatial and material records of our individual and collective pasts. Increasingly, landscapes are recorders of the exploits of capitalism, colonialism, violence, and climate breakdown. Considered on their own, these investigations and landscapes are intimately tied to the materiality of their locations. But as the Forensic Architecture team has written, “Limiting the scope of inquiry to questions of direct casualties neglects some of the most crucial destructive effects of conflict — deforestation, population transfer and concentration, land use and economic transformation — and limits our historical understanding.”12 In the Guatemalan highlands, records of environmental violence tells us the story of the Ríoss Montt dictatorship and of the intersections between military and state control, the seizure and resettlement of people, regional changes to urban, agriculture, and forest areas, and the genocide of a people. “A more complete political account of conflict,” the Forensic Architecture team writes, “would demand an understanding of what we would like to call “field causality” — aggregate causes that apply, like a force field, from all directions, involving various agencies and modes of physical transformation to shape a specific reality.”13 In the case of Guatemala, new, distinct ecologies of matter combined mineral and rock and soil formations with the ruins of buildings and human remains to become legible as the strata — a geological record — of genocide.

“But personal responsibility,” Forensic Architecture insists, “and the mechanisms established to determine and address it, must be complemented by an understanding of the slower — though no less lethal — consequences of environmental violence.”14 Could Forensic Architecture’s methods in determining “field causalities” of “environmental violence” be extended or applied elsewhere, developing new understandings while demanding new forms of justice? In this age of climate breakdown, with multiple and often times layered and indirect causes, how might we understand and assign not only individual, but political responsibility for the end of life — human and more-than-human — that is the result of the destruction of the conditions that support it?