The contradiction of conceptual art is that it remained in many ways modernist. Though critical of modernism’s formalism and its idealist agenda, the concerns of conceptualism were about how art acquires its meaning.

Back in style and in demand, conceptual art makes a fitting subject for a magazine supplement. Like real estate or audio equipment supplements, this special section deals in promotion and luxury goods. But a supplement is a small magazine that can interrupt the seamless flow of a glossy art monthly. What better way to present conceptual art, which has often materialized within magazine pages and has displayed a persistent self-consciousness in regard to institutional frames.

The platitude that all art after Duchamp is conceptual is, in many ways, correct. Conceptual art is earth art. Conceptual art is Arte Povera. Conceptual art is minimal art. Pop art is, in a sense, conceptual art. The 1950s and 1960s work of Jasper Johns, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Robert Rauschenberg, and the other post-WWII art that has some critical and ironic relation to its status as aesthetic practice is conceptual. It was with the historical avant-gardes of the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s (such as Dada, Surrealism, and the Soviet experiments) that art as an institutional category was recognized. Modernism had historically unfolded, and artists began to work outside of painting frames, beyond the limits of pedestals. When Marinetti, Duchamp, and the diverse alliances of the international avant-garde wreaked havoc upon the cultural contingency of meaning, artists moved from morphological questions (how to make a painting or sculpture look different) to questions about the production of meaning and value and what makes a particular object or practice into art.

Neo-conceptualism, the most recent addition to the conceptual canon, has flooded the galleries during the last few seasons and has brought with it a recycling of earlier conceptual art. Much of the new work has the cool and intellectual look associated with conceptualism but it functions primarily, if not completely, as luxury goods. And much of this new conceptualism (an all-embracing term applied to neo-pop, neo-minimalism, and neo-geo), as well as a good deal of the older work, are instantaneously absorbed by a highly developed art apparatus and are missing the complex relation between artistic production and systems of reception and dissemination that has always been the critical ingredient of conceptual art.

This supplement foregrounds recent art that has appropriated and reworked conceptual strategies in order to function as something more than fuel for the commercial system. There are projects created especially for Flash Art, like Alfredo Jaar’s revaluation of the magazine’s table of contents, Louise Lawler’s art magazine ad, and Silvia Kolbowski’s fictitious interview. There are pieces that have been conceived especially for a magazine page, like Hans Haacke’s “artvertorial,” which was first published in the corporate culture magazine Manhattan, inc. in 1987; and Group Material’s ad, which is an extension of their concurrent project at the Dia Art Foundation in New York titled Democracy. And this supplement is itself supplemented by artists’ interviews and statements that provide multiple views of what conceptual art has been historically and how it relates to the current situation. As an introduction, this supplement will present one reading of a particular moment of conceptualism, that is, from the second half of the 1960s to the early 1970s when the term conceptual art gained currency, when this type of work was received as a specific configuration, and when groups of artists reduced their production to language.

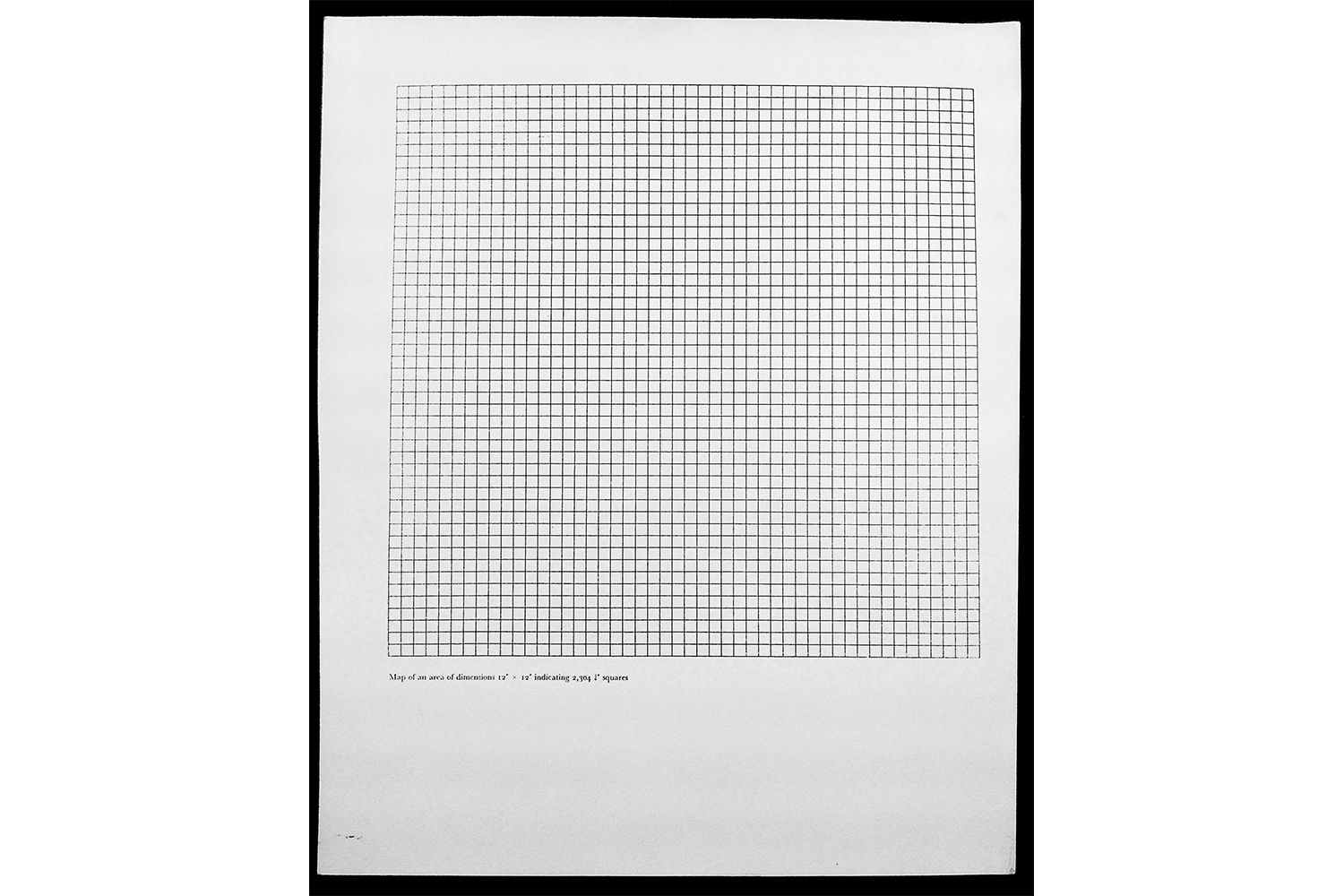

During the second half of the 1960s, an increasing number of artists began producing word-objects, installing textual pieces in galleries, printing statements in catalogues, magazines, newspapers, and on billboards, and they began publishing essays about art. In 1965, On Kawara began making location paintings — the image was the longitude and latitude where they were made. In 1966 he began to use the date as his image and to save clippings from that day’s newspaper as part of the piece. This was when Hanne Darboven began to produce her number pieces based on indexing systems, marking time with her daily writings for her drawings/books. In 1965, Joseph Kosuth was installing definition pieces like One and Three Chairs (the first in the series comprising an actual chair, a photograph of a chair, and a dictionary definition of “chair”), and in 1966 he initiated his body of work subtitled Art as Idea as Idea, begun when he reproduced a photostat of a dictionary definition of the word “water.” In Britain, Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin were producing collaborative projects, like their declaration series of 1967. One “piece” of the series was the Air Show, in which they declared one square mile of air to be art. A text exploring the logical geography of this proposition was subsequently published in 1968 by Art & Language Press. In the second half of the 1960s, artists were publishing pieces in magazines, journals, and newspapers: Dan Graham printed his Schema in Aspen in 1967; Ian Wilson took out an “ad” of his name in the June 16, 1968, Sunday New York Times: and Kosuth’s Second Investigation of 1968 comprised thesaurus entries in magazines and newspapers. Robert Barry did statements that were descriptions of invisible situations or abstractions. Stanley Brouwn used texts to document his walks. Douglas Huebler produced photo-text pieces. Lawrence Weiner used statements to generate site-specific demarcations. Victor Burgin, Ian Burn, Adrian Piper, and Mel Ramsden were among the artists who were producing texts and books as their art. This line up of individuals provides a conventional and representative sampling of the artists who began to restrict their work to the field of language.

To map out this very specific historical and theoretical moment of mid-1960s and early 1970s conceptualism, however, could easily turn into a list of who did what first.1 And this approach to writing history ignores the fact that conceptual art ever happened, in that conceptualism’s important revaluations regarding how meaning is produced are not taken into account. Implicit in reducing aesthetic practice to language is an avowal that creativity, self-expression, and subjecthood are not constituted within the absolute domain of the individual psyche, but are constructed within a fluid interchange of cultural codes realized in specific contexts. Conceptual art was not a series of one-person shows, nor was it a selective collection of individual pieces. Rather, it came into formation within collective partnerships and projects which took shape within magazines, journals, newspapers, catalogues, books, and exhibitions. Conceptual art as a distinguishable construct, the issues engendering it, as well as its importance to the current situation are better served by an institutional perspective.

Art & Language is a paradigm of the institutional critique within which conceptual art was constituted. The most all-embracing and the most consolidated of the conceptual collaboratives, Art & Language was at once theoretically discursive, volatile in terms of “membership,” and tolerant of the absurdist ironies that often accompanied the high seriousness of its arcane texts. Through the years the group has taken on many of the key issues of conceptualism and has intersected with many key conceptual artists, projects, exhibitions, and organizations. Art & Language Press was formed in May 1968 by Atkinson and Baldwin, along with David Bainbridge and Harold Hurrell in Coventry, England.2

The Press’s first ventures were the statements/books of Atkins and Baldwin, which included the Air-conditioning Show / Air Show/ Frameworks (1966), and Key to 22 Predicates: The French Army (1967). Exactly one year later, they went on to found the journal Art-Language. All four artists had been collaborating with dematerialized and textual pieces as well as with projects that involved site-specific installations and technology. Art-Language volume 1, no. 1 (printed with the subtitle Journal of conceptual art, which was subsequently dropped), begins with an introductory essay that circles around the question “can this editorial come up for the count as a work of art within a developed framework of the visual art convention?” The first issue also carried tongue-in-cheek articles by Bainbridge and Baldwin, who explore the limits of aesthetic criteria within the proposition of an alien from another galaxy being invited to exhibit art in a gallery. Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art, which had originally been published in Artforum in 1967, were included,3 as were Graham’s Schema (an ontological description of a magazine page) and a set of Weiner’s Statements.

In July 1969, Kosuth (who would publish his important “Art After Philosophy” in Studio International in the fall of 1969 and who by the following summer would be called “the Savonarola of conceptual art” by The New York Times) was invited to be Art-Language’s American editor. With the second issue in February 1970, Kosuth was on the masthead and Burn and Ramsden, who were then in New York, were among volume 1, no. 2’s new contributors. In 1971, Burn and Ramsden became editorial associates, as did Charles Harrison, who became the general editor of Art & Language Press. (Harrison had been supporting conceptual art through his writing and editing — before joining up with Art & Language he had been an editor of Studio International). Art-Language was published until 1985, and among its many contributors were Michael Corris, Michael Thomas, Graham Howard, and Philip Pilkington. By the mid-1970s, founding members Atkinson, Bainbridge, and Hurrell had left the partnership, and presently Baldwin and Ramsden work as an Art & Language collaborative.

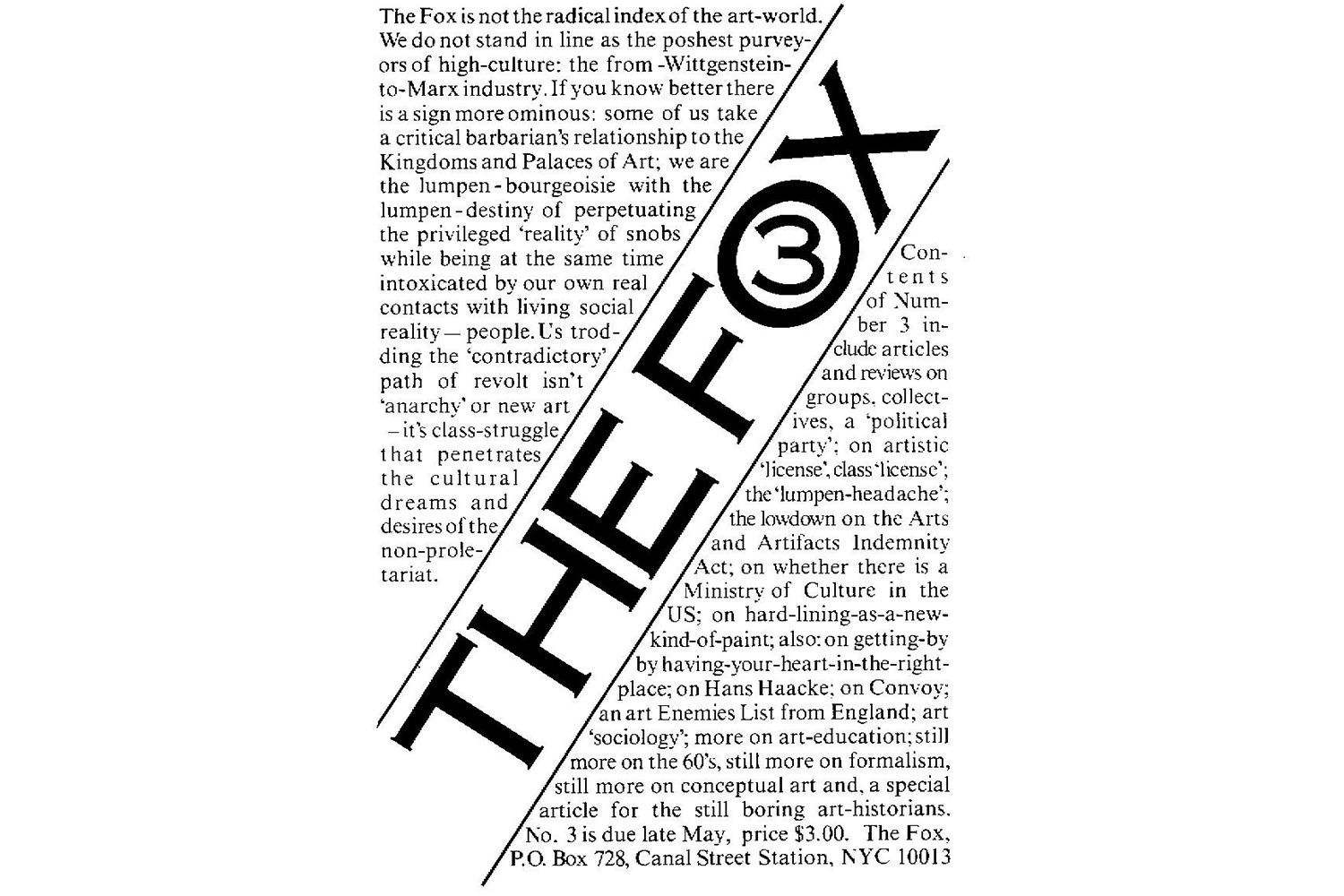

Until the mid-1970s, Art & Language maintained a changing cast of characters and a protean public image. The Art & Language Institute (1971–72) was the name under which the group entered Documenta 5 in 1972. Art & Language Limited was an attempt to form a company; it was registered as a private corporation in Great Britain but little else came of it. The Art & Language Foundation, Inc. published The Fox, which ran for three issues out of New York in 1975 and 1976. The Fox was edited by Kosuth, Ramsden, Sarah Charlesworth, Corris, Preston Heller, Andrew Menard, with Burn as reviews consultant. The stated purpose of the journal was “to establish some kind of community practice [for] the revaluation of ideology.”4 Ironically, perhaps appropriately, there was a moment of tremendous strife within The Fox’s editorial community. The Fox marked the beginning of a continental divide between Art & Language-US and Art & Language-GB. The poster for the first issue promised explorations into the “cultural responsibilities of art in the post-modernist period” and, not surprisingly, with almost a decade of conceptual art to reflect upon, “the failure of conceptual art.” Charlesworth’s introductory editorial stressed the institutional character of art and took issue with the limitations of art as idea. The Fox was Marxist, and its articles were within a spectrum that included “A Note on Art in Yugoslavia” to “Pricing Works of Art.” Another journal briefly associated with Art & Language was Analytical Art. Published from 1971–72 by students at Coventry College of Art, where Atkinson, Bainbridge, and Baldwin were teaching, Analytical Art was absorbed within Art-Language when Bainbridge and Baldwin were fired from their positions for teaching art theory.5

Art & Language manifested the concerns and contradictions of conceptualism in its most expansive and most reductive aspects. Most of the other conceptual collectives and collaborative projects were short-lived or ad hoc, and had many different participants.6 In 1967, Kosuth, Christine Kozlov, and several other artists founded the Society for Normal Art, which lasted for several months. The Society ran a gallery space (The Museum for Normal Art) and held exhibitions like “15 People Present Their Favorite Book” (among them were LeWitt, Robert Morris, and Robert Smithson). In 1969, Burn, Ramsden, and Roger Cutforth formed The Society for Theoretical Art and Analysis. The artists in this society exhibited as a group, held meetings, and issued deliberations or “proceedings” that were distributed among friends and interested parties. N.E. Thing Co. was primarily Iain Baxter, who would occasionally collaborate with other artists under the N.E. Thing logo. Art & Project, founded in 1968 by Adriaan van Ravesteijn and Geert van Beijeren, had a gallery space in Amsterdam that dealt with architecture and art, and which became a conceptual art forum. Its bulletin (which continues to be published) is an exhibition in its own right. Among the artists associated with Art & Project were Barry, Darboven, Huebler, Kosuth, and Weiner.

In 1971, Art & Language members agreed to use the journal Art-Language as the sole outlet for their production. But invitations to exhibitions and the sheer economics of working within a system founded upon the consumption of luxury goods made this almost immediately untenable. Nevertheless, the journal remained a primary site for their work — one that dismantled the boundaries separating production, reception, and distribution. By functioning as critic and publisher as well as curator and dealer, Art & Language, in a sense, became a system unto itself. As was the case with the more successful contributions to conceptual art, Art & Language’s method of working can be seen as a series of experiments that laid bare the historicity of the institutions that engender and validate art.

Conceptual artists’ desire to take on the entire institutional framework is representative of the demands of the post-WWII situation. Different from early modernism, when artists produced a category of goods that was created and received as a free-floating world unto itself (a Mondrian painting for example), and different from the historic avant-garde’s attempt to participate in the creation of a mass media (for instance Herbert Bayer’s advertisements, propaganda, and exhibition designs), the major post-WWII artists have had to accept the limitations of performing within what was becoming a highly institutionalized subculture. The utopianism of the first half of the century was replaced by an ironic relation to aesthetic production. This attitude came with an awareness that no matter how ambitious or untraditional the work might seem, it remained squarely within the confines of art as one aspect of high culture’s contributions to leisure time activity. Before WWII, the unique modern masterpiece and the innovative avant-garde project were the powerful catalysts which functioned in relation to a fledgling art apparatus. After WWII (when most work can be seen as neo-something, whether it is American-type painting, neo-Dada, or neo-geo), the systems of reception, distribution, and promotion are what are novel and powerful.

This strengthening art apparatus of the mid-1960s and early 1970s was confronted and made visible in experimental mergers among the discrete branches of the art world. There was a general tendency for the artists to act as producers/critics/curators/dealers and to take over administrative tasks. The extreme end of this practice was when artists (following many obvious precedents like that of Yves Klein) would turn off the lights and lock the doors of the gallery as their aesthetic gesture. Robert Barry, for one, did a series of gallery pieces in 1969 at Art & Project, at Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles, and Galleria Sperone in Turin where, for the duration of exhibitions, notices were posted and the spaces were closed. The other side of the coin was the hybrid activity of the administrators/curators/critics like Harrison, Lucy Lippard, and Seth Siegelaub.

Publisher, curator, and art entrepreneur Siegelaub personified the producer as artist. In November 1968, he produced Huebler’s one-person show that existed solely as a catalogue. In the following year, he curated the “March 31, 1969” show, in which thirty-one artists were each assigned one day of the month. Their catalogue contributions were published as the exhibition and distributed free of charge internationally. Siegelaub’s “July-September 1969” consisted of eleven artists (among whom were Barry, Kosuth, LeWitt, N.E. Thing Co., Smithson, and Weiner) who did pieces in eleven different locations around the world and whose documentation was brought together in the catalogue. For the “July/August” exhibition in Studio International, he invited guest curator/editors, who invited artists to create site-specific pieces for that issue. Siegelaub’s restructuring of exhibition as catalogue, magazine as exhibition, exhibition as text, was as creative as what artists were doing and in many instances his ideas were more so.

Lippard, like Siegelaub, was a critic doing projects indistinguishable from artists’ work. In the “Information” show at MoMA in 1970, she was included as one of the artists in the exhibition. And in another of Barry’s gallery pieces at Yvon Lambert in Paris in 1971, his exhibition consisted of Lippard’s catalogues, her unpublished review of the show, and some additional commentary. The November 1969 Artforum review of Lippard’s group exhibition “557,087” described the curator as the show’s true artist: “Her medium is other artists, a foreseeable extension of the current practice of a museum’s hiring a critic to ‘do’ a show and the critic then asking the artists to ‘do’ a piece for the show.”7

Lippard’s “557,087” was among the highly visible international group exhibitions that provided arenas for work involving collaboration, site-specificity, and the primacy of language. Beginning in 1967 in New York there were a series of exhibitions at the Dwan Gallery titled “Language to be looked at and/or things to be read.”8 Generally known as Language I, II, III, and IV and running every year until 1970, the shows included avant-gardist poetry, minimalism, as well as language as visual art, and they brought together for the first time the work of such artists as Kosuth, Art & Language-Great Britain, Arakawa, On Kawara, and Dan Graham, and showed them with pieces by Carl Andre, LeWitt, Morris, Johns, Ad Reinhardt, and early modern prototypes such as Duchamp, Marinetti, Magritte, and Picabia.

By 1969, conceptual art was taking its place alongside Arte Povera, earth art, minimalism, and process art in the large international showcases. A landmark exhibition, “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form: works-concepts-processes-situations-information,” was organized by Harald Szeemann, at the Kunsthalle Bern in spring of 1969. The show brought together textual pieces like Kosuth’s 1. Space (Art as Idea as Idea) and Darboven’s six Xerox books from the year 1968; site-specific works like Richard Artschwager’s 40 blps and LeWitt’s Wall Markings; Arte Povera works such as the two by Jannis Kounellis (a charcoal piece and one made of sheepskin, wood, and rope); and dematerialized projects like Yves Klein’s Immaterial Work from 1962. The exhibition was organized to open simultaneously with “Op Losse Schroeven: situaties en cryptostructuren” held at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, which had less language and concept work. The “Op Losse Schroeven” catalogue essay by Piero Gilardi makes a case for the shared agendas of the radical political situation in Paris the year before, the Haight-Ashbury community in San Francisco, more distant political upheavals like the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and the art world’s neo-avant-garde projects. Gilardi felt he was witnessing a global phenomenon whereby traditional ideological and institutional structures in the visual arts and in everyday life were disintegrating.

Although the art world was observing and participating in this internal critique, at the same time it was consolidating itself to an even greater degree. Representative of this situation was the proliferation of these highly organized, large-scale international exhibitions that were comprised of work at odds with the institution of exhibitions. What’s more, Philip Morris, who inaugurated corporate support for the arts in 1966, was the sponsor of “When Attitudes Become Form.” The company’s visibility in the catalogue (the cover is printed with “An exhibition sponsored by Philip Morris Europe” in the same size lettering as the show’s title) is unusually accentuated even by 1980s standards. This seems to be the first international show of this scale to be funded by a corporation. The telling irony is that the company was supporting work that was constituted as a critical response to developments like Philip Morris’s landmark venture.

In Europe in the Fall of 1969 there were more conceptual-oriented exhibitions, including “Prospect ’69” held at the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, and a more specifically language-oriented exhibition, “Konzeption/Conception,” at the Städtische Museum, Leverkusen. In September in the US “557,087” opened at the Seattle Art Museum (557,087 was Seattle’s population at that time). The site-specific exhibition took a slightly different form when it traveled to Vancouver as “955,000” and to Buenos Aires as “2.972.453” in 1970. In the summer of 1970 in New York the important “Information” show was held at the Museum of Modern Art, and a slightly tighter presentation of primarily language/text work, “Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects,” was mounted at the New York Cultural Center.

This activity reached a grand crescendo at the 1972 Documenta 5, where works by more than one hundred and fifty artists were brought together. The show was arranged according to broad-based themes such as Science Fiction, Social Realism, Art of the Insane, Political Propaganda, Information, Idea, and Idea/Light, to name several of the categories. But conceptual art was a strong presence in both the exclusively textual work and the more hybrid uses of language. For example, Art & Language, Barry, Burgin, Darboven, and Weiner were represented, and there were important projects like Marcel Broodthaers’s “Musée d’Art Moderne: Département des Aigles,” Hans Haacke’s “Visitors’ Profile” (which was published simultaneously as a Flash Art cover), and Joseph Beuys’s information room. Beuys actually set up an “office” for discussion and proliferation of material for the Organization for Direct Democracy, and at one point became involved with the search and the ensuing controversy around the Baader-Meinhof group.

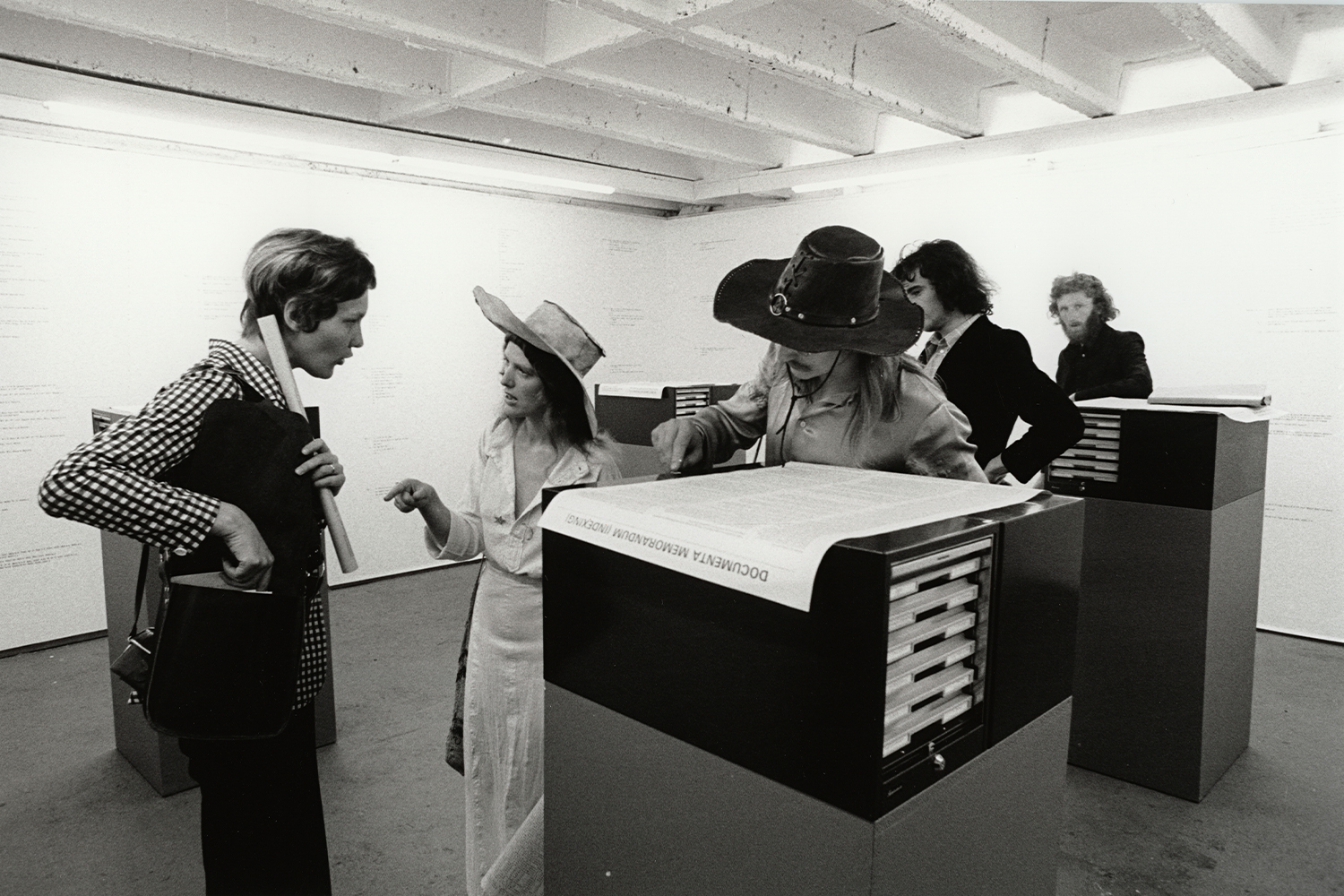

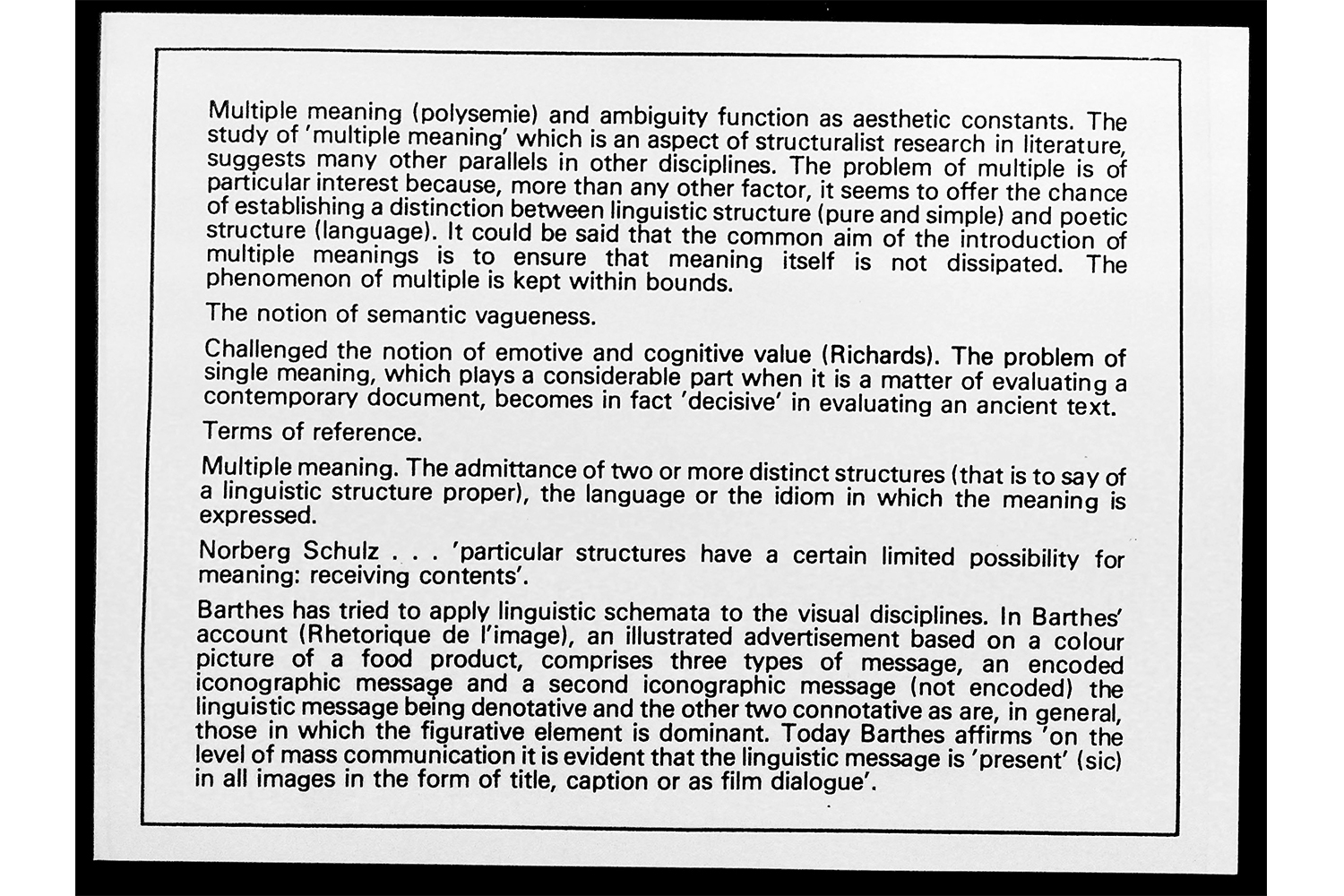

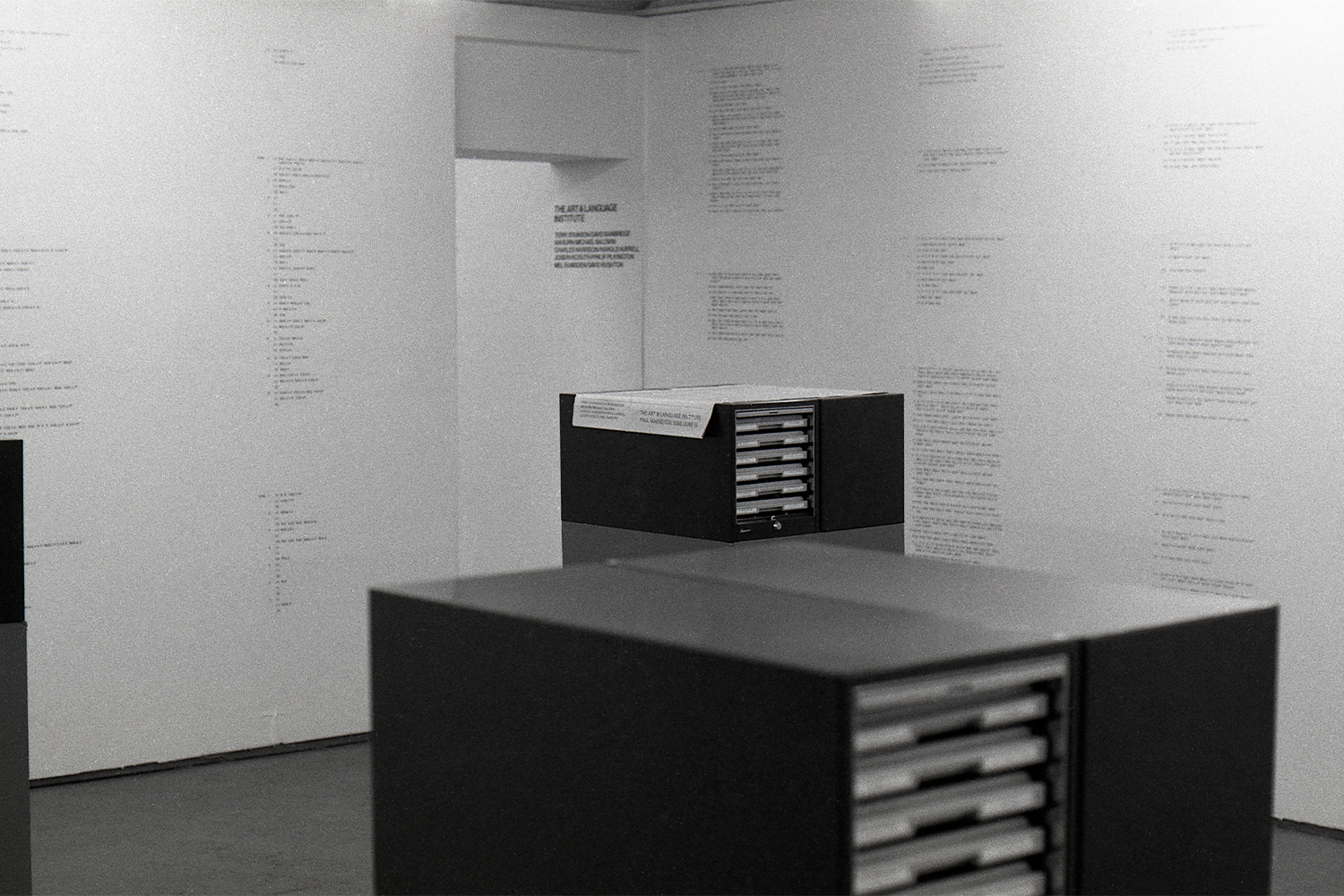

Art & Language, on the other hand, kept their project strictly within the proposition of how art comes to have meaning and, specifically, how their work functions in terms of meanings. In a moment of consolidation for the group, Art & Language exhibited their first index — a series of file cabinets containing all the materials published or considered for publication in Art-Language.9 Following a system devised by Baldwin, the texts were subdivided into approximately 250 sections. Each section was read (sometimes collaboratively, sometimes individually) in relation to each of the other sections, creating 122,500 pairs of comparisons which were then assigned a category within three possibilities for ideological or logical compatibility: (=) compatible, (–) incompatible, or (T) transformation of logic. Photo-enlarged lists of the results of these comparative readings for each text were posted on the walls. This labyrinthine installation can be understood as an index map where the theoretical domain within Art & Language was constituted. This room of file cabinets materialized a critique of modern art’s idealist project, and served as a visual model for the production of meaning that was collaborative, relational, and disseminated.

The sovereignty of individual creation and unmediated expression had no place within this communal and publicly posted system generated by quorums of readings. A paradigm of the systematic and collaborative character of conceptual art in general, and of Art & Language in particular, the project provided a radical critique of modernism’s investment in liberal humanism and the orthodoxy of the unfettered will of the individual, which has traditionally been understood as finding its release in art.

Conceptualism’s recognition of the historicity of liberal humanism took official form in the catalogue, where multilingual versions of “The Artist’s Reserved Rights, Transfer, and Sale Agreement” were published. To own property and to exchange goods are the legal foundations of capitalism. In the Anglo-American system, for example, subjecthood in the modern era is characterized by the two fundamental rights of property and contract.10 Exploiting the ideology of liberal humanism and the free market, the contact secures the rights of an artist as a legal subject. Taking up similar issues, but not directly related to “The Agreement,” there were several challenges made by artists to the exhibition organizers. In keeping with conceptualism’s revaluation of the discrete components of the art apparatus, a number of artists demanded that participation in the show should be without censorship, that their work should not be classified or installed without the artist’s approval, and that the artist should be given administrative and budget information.11 The demands were published as a signed statement in Artforum in June 1972. Several artists withdrew from the show, among them Robert Morris, who also printed the requests as a letter in Flash Art, May–June 1972.

The contradiction of conceptual art — what might be called its failure — is that it remained in many ways modernist. Although these projects were critical of modernism’s formalism and its idealist agenda, the concerns of conceptualism were about how art acquires meaning. The conceptual artists’ approach to the construction of meaning is demonstrated by their synthesis of analytic philosophy, and of Wittgenstein in particular, where language and, in turn, art are treated as autonomous systems. Conceptual artists’ decision to work with texts rather than pictures was an attempt to foreground the fact that representation is produced through convention — what is described by Wittgenstein’s often-cited statement, “The meaning is the use.”

By the mid-1970s, after almost a decade of conceptual experimentation, many artists began to deal with the limits of their formulations. They began to reevaluate the historicity of language in terms of a specific social fabric and to confront the “reader in the text.” In the summer of 1972, in Art-Language volume 2, no. 2, Burgin took issue with Art & Language’s “analytic” hermeticism and their “l’art pour l’art” position.12

He offered a different set of problems to be addressed, introducing linguistics and specifically Ferdinand de Saussure’s work as a model for dealing with language and art. Burgin pointed to the fact that reality is mediated by cultural codes. “Linguistics has demonstrated that the conventional notions of ‘reality’ held in society are not simply transmitted by the language of that society but are to an extent produced by that language. […] art is only partially autonomous [and its function] is to modify institutionalized patterns of orientation towards the world and thus to serve as an agency of socialization.”13 In 1973, Burgin began his move away from primarily textual pieces and was incorporating images with texts, which had been a common practice in the 1960s and early 1970s, but Burgin was appropriating advertisements as a means of dealing with the construction of subjectivity in terms of class within mass-media representations. The Fox magazine can also be understood as an attempt to “reclaim art as an instrument of social and cultural transformation,” as it was described in the introductory statement of the second issue. Kosuth, writing in The Fox in 1975, reformulated his earlier position, referring to the failure and death of conceptual art. He called for an “anthropologized art […] obliterating art ideologies which presuppose the autonomy of art. […] What began in the mid-1960s as an analysis of the context of specific objects (or propositions) and correspondingly the questions of function, has forced us, now, ten years later, to focus our attentions on the society and/or culture in which that specific object operates.”14 Kosuth moved from his 1960s photostat definitions that were hung on the wall to reading rooms in the early 1970s (his Eighth Investigation, for example), in which the viewer became the reader who unified found fragments of texts; and, in the late 1970s, his Text/Context, in which, for instance, texts installed in exhibitions and on billboards addressed the viewer. By the second half of the 1970s, Art & Language-Great Britain was using images with texts and making paintings that were ironic and heavy-handed exaggerations of radical politics — what they called their “Black Propaganda.”

In the mid-1970s, the theoretical canon among conceptual artists was shifting from primarily analytic philosophy to more Marxist, sociological examinations of culture found, for example, in the work of Frankfurt School critics, such as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse, and to the semiological investigations of Saussure and Roland Barthes. This concern with class and the social construction of meaning opened up the field to feminism, the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, film studies, and a more broad-based assimilation of poststructuralism. In Britain, Screen magazine served as a vehicle for the establishment of this discourse, and the journal serves as a document of these changing concerns. This shift of emphasis within the theoretical activity was consonant with conceptual art’s expansion of its concerns beyond the framework of art to the unlimited domain of representation.15

Mary Kelly’s work is a paradigm of the reframing of conceptual strategies in order to take up issues dealing with representation and specifically with the construction of a feminine subjectivity. Conceptual art of the 1960s and early 1970s accepted the language of white, Western patriarchy as a neutral standard. Kelly questioned the authority of this language and dealt with the fact that we come to know ourselves and the world through our gendered, historically specific representations. According to the artist, several conceptual art exhibitions in the early and mid-1970s in London contributed to her formulation of the Post-Partum Document of 1973–79, which she sees as both informed by and polemically directed at late 1960s and early 1970s conceptualism.

Kelly appropriated the anti-expressionist, serial format of conceptualism, found for example in Darboven’s work, and used it to display highly charged fetishistic baby souvenirs — blanket fragments, handprints, dirty nappies — which are framed by (and on a certain level are a supplemental articulation of) elements of Lacanian theoretical analysis. The document is a diary about the poignancy of weaning the child away from the mother and the child’s entry into the patriarchal order. The project opened up new territory for the visualization of the feminine and provided a place within which to articulate the construction of intersubjectivity. In Kelly’s current project, Interim, she continues to work with traditionally “unarticulated” and intermediate regions of representation — women during middle age.

Kelly’s work is part of a feminist revaluation of subjectivity in late capitalism that has served as a catalyst for going beyond questions of class, gender, and sexuality to issues such as race, ethnicity, and the first world’s relations to developing notions. Artists like Lothar Baumgarten, Jaar, Kolbowski, and Barbara Kruger rework the strategies of conceptualism and use the art world as an arena to examine these concerns. Others, such as Haacke, Louise Lawler, and Antoni Muntadas, continue conceptualism’s interest in looking at the way the apparatus functions, but do not treat the art world as an autonomous category. A quotation used in a recent Haacke piece, The Saatchi Collection (Simulations) (1987), states it simply: “Everything is connected to everything else.” The quote is from Lenin, which Haacke took from a Saatchi & Saatchi ad agency annual report. In the art world it is common knowledge that Charles Saatchi and his brother Maurice run the largest ad agency in the world, just as it is common knowledge that Charles Saatchi and his wife Doris are probably the most powerful collectors of contemporary art. Haacke has made it his business to make it known that Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide continues to do business with South Africa (one of their affiliate agencies has gone as far as producing a pro-apartheid advertising campaign). Affiliations like this one lay ruin to a modernist faith in the autonomy of art.

Conceptual art, however, does not have to be political in the conventional meaning of the term. Conceptualism is work that interacts with aesthetic institutions of production, distribution, and reception in critical, conflicted, and revitalizing ways, providing something more than a currency composed of aesthetic objects. And conceptual artists no longer restrict themselves to texts, but respond to and incorporate the seductive possibilities of the mass media. As General Idea has described their relation to the mass media, “We want to add to it, stretch it until it starts to lose shape, stretch that social fabric.”16 Implicit within conceptual practice is a demonstration that the way we know ourselves and the real is through our representations. We create them. We can make them different. But this selective enumeration of this supplement’s projects, statements, and interviews does a disservice to these contributions — they have the power to speak for themselves.