Cole Lu has home on his mind when I call at the end of January. The Brooklyn-based artist is planning his first trip in five years to Taipei, where he grew up. Lu reflects on his expansive practice, which, over the course of 2022 alone, has resulted in the shows “Millennium Approaches” at Nir Altman in Munich and “The Temple of Sleep” at Chapter NY in Lower Manhattan. Below, he briefs me on the personal and professional triumphs in his life since our first meeting several years ago.

Thora Siemsen: We met at a dinner through friends of ours, the poet Paul Legault and graphic designer Joseph Kaplan, years ago. Remind me, where did you all meet?

Cole Lu: We met in St. Louis when I was at Washington University getting my MFA in visual art. Paul and Joseph moved there for Paul’s writer-in-residence job at WashU teaching poetry to MFA students.

TS: I remember a long subway ride you and I shared after that dinner. I was reading Qiu Miaojin’s Last Words from Montmartre and we talked about it.

CL: Oh my god, yeah, I remember that. I read Qiu Miaojin in Mandarin when I was in middle school. I have not yet dived into the English version of Last Words from Montmartre. I thought what was stopping me from doing so was the imprint of my mother tongue, and it makes it a very tender place to approach something once familiar with a set language from a different system of culture.

TS: I reread it the other afternoon to get back into that headspace. I knew she was also from Taipei.

CL: It’s an amazing coincidence that our interview is happening right now. I have not been back to Taipei for almost five years, but I’m going in March. I’m thinking about Taipei in terms of re-encountering the old self, trying to get my mind ready for that. It took a while for me to better understand my identity, my relationship to my body, my sexual orientation, my gender, and where I can locate myself professionally in art… It would not be imaginable for me if I had lived in Taipei for the past decade. It would also be challenging to imagine comfortably reaching my current capacity to move around in the world in a nonbinary body. The notion of trans rights and identity was nonexistent in my upbringing, which means there was no proper mirroring during that time.

The context of Qiu Miaojin’s struggle was this profound sadness and loneliness, in which you were unable to be understood yet craving so much to be so. Qiu Miaojin died a lesbian, but I think she died wanting to be a man in many ways. The impact of that emotion comes in waves for me. Either you choose to end the life that you have right now, or you exist as freely as you can while accepting that violence towards “the other” is outwardly expressed, even nowadays.

TS: What’s bringing you back?

CL: Family. I have not seen my family for a very long time in person. The last time I saw my parents, they flew from Taiwan to come to my show [“The Dust Enforcer (All These Darlings Said It’s the End and Now US),” Deli, New York] in 2019. That was right before COVID-19. At that time, I had planned to visit Taiwan annually. That was right after I got my green card. I was able to travel more without worrying about meeting a lot of criteria for the artist’s visa. Unfortunately, after that COVID-19 hit. I’m excited to see them in person.

TS: Your international art career has been on the boil since we met. Can you catch me up on what the last few years have been like for you?

CL: My career got busy unexpectedly, mainly because the element of time stretched into a very abstract understanding. Working is always a form of coping or a grounding device. I keep a pace of making work that calms and soothes me, despite high volume. During the pandemic, I was able to have my work circulate in different countries or on various platforms through shipping and transportation. When everything reopened, some shows that were already in conversation came out. The unexpected part for me was the physical participation. It looks like a lot is happening at once, but this is also the accumulation of the delay.

TS: What is your latest work like?

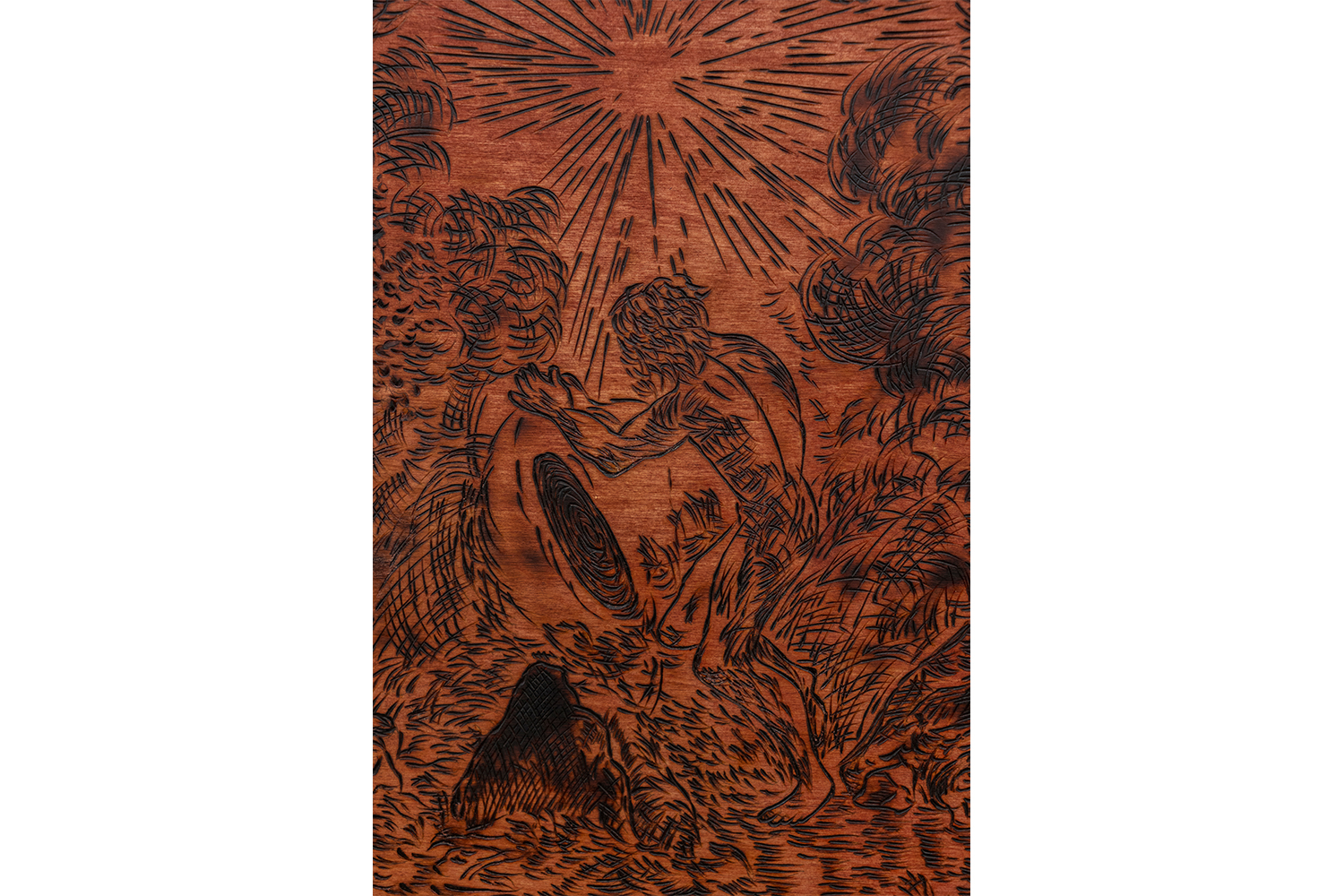

CL: My latest work, “Millennium Approaches” (2022),is a continuation of world-building through mythological retelling, combining literary and historical references with autobiographical connotations. It also continues my work “The Temple of Sleep,” which is set on the moon. The protagonist Geryon (a character from the tenth labor of Hercules: the Cattle of Geryon; Stesichorus’s “Geryoneis”; Dante’s Inferno; and Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red) discovers the moon is his birthplace, where the man-bat (from the story published by the New York Sun in 1835, later referenced as “The Great Moon Hoax”) resides, a humanoid being with bat wings. He has returned home from Earth and arrived at the Temple of Sleep, and it was a place where hypnosis, sleep, and healing occur. It was also where he left the old self that he had utterly forgotten, who is entirely unknown to himself now. The reencounter of one’s shadow is the quest of the story. “Millennium Approaches” follows the story and further unearths evidence of old accounts, and they present as relics, fragments, a portrait, a landscape that freezes the moment of that reckoning. Most of the works are shown in the form of pyrography (woodburning), as I intended to rewrite the story with fire as a gesture of prehistoric storytelling, coming from one step before we learned to use burnt wood (charcoal) to make cave paintings.

For me, the prehistoric storytelling aspect is intended to tell a story that is not rooted or generated by any established hierarchy that furthers class struggles in language, social, geographical, political, and economic differences. Other gestures in petroglyph art, such as incising, carving, or abrading, are also applied to sculptures and other wall works. Both solo presentations question a potentially erased history from the viewpoint of “the other” in a historical context. Since such perspectives often failed to exist, they became a myth, a tale, a saga, or a legend, depending on the narrator.

In my recent show at Nir Altman in Munich, the title piece, When he was born… (“Millennium Approaches”) (2022), is a composition of a sculpture made with a historical relic — a pair of cast-iron astronauts made during the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union, combined with marble, steatite, and burnt cypress. The sculpture references the atrium and peristyle in Roman households, as the statue suggests a household value and potentially a monument (see the dancing faun statue at the House of the Faun in Pompeii). What was holding the cast-iron astronauts was a green marble engraved with a scene of the green lion eating the black sun, an alchemical symbol of chemical transformation. The sun was originally gold, which symbolizes the ego. The black sun was a chemical process of darkening matter (gold). And the black sun as a symbol was used as a symbol of Nazi Germany and later neo-Nazis. The green lion represents instincts but is also primordial, an unripe color. It also connotes fecundity. The lion turns red after consuming the black sun. Eating the sun symbolizes the dominance of the ego by instinctual forces. It is the beginning of a return to a more natural psychological state of a human being without vertical hierarchy or colonizing nature. Underneath the green marble is a rectangular column made of steatite rock; it was carved with natural elements that symbolize fire, air, water, and earth on each side. It references stones in the 1997 film The Fifth Element. Lastly, the burnt cypress holds the form of the atrium at the base. An open central court contained the impluvium, a basin where rainwater collected. The final frame is always the title, as they’re often the most personal and usually arrive last.

A lot of time, I think a gratifying surprise in the making is when the material language, the gestural language, and the written language hold the sentiment that I have yet to foresee in the process of making. This piece is one of the works I keep going back to. Hypnos is the god of sleep; he dwelt in the land of eternal darkness beyond the gates of the rising sun and rose into the sky each night in the train of his mother Nyx (night). The encounter with Hypnos, as a lover, as an enemy, as the repressed self, or as “the other” remains open. The composition regards the fragmentary nature of the collage as the compass of systematic displacement.

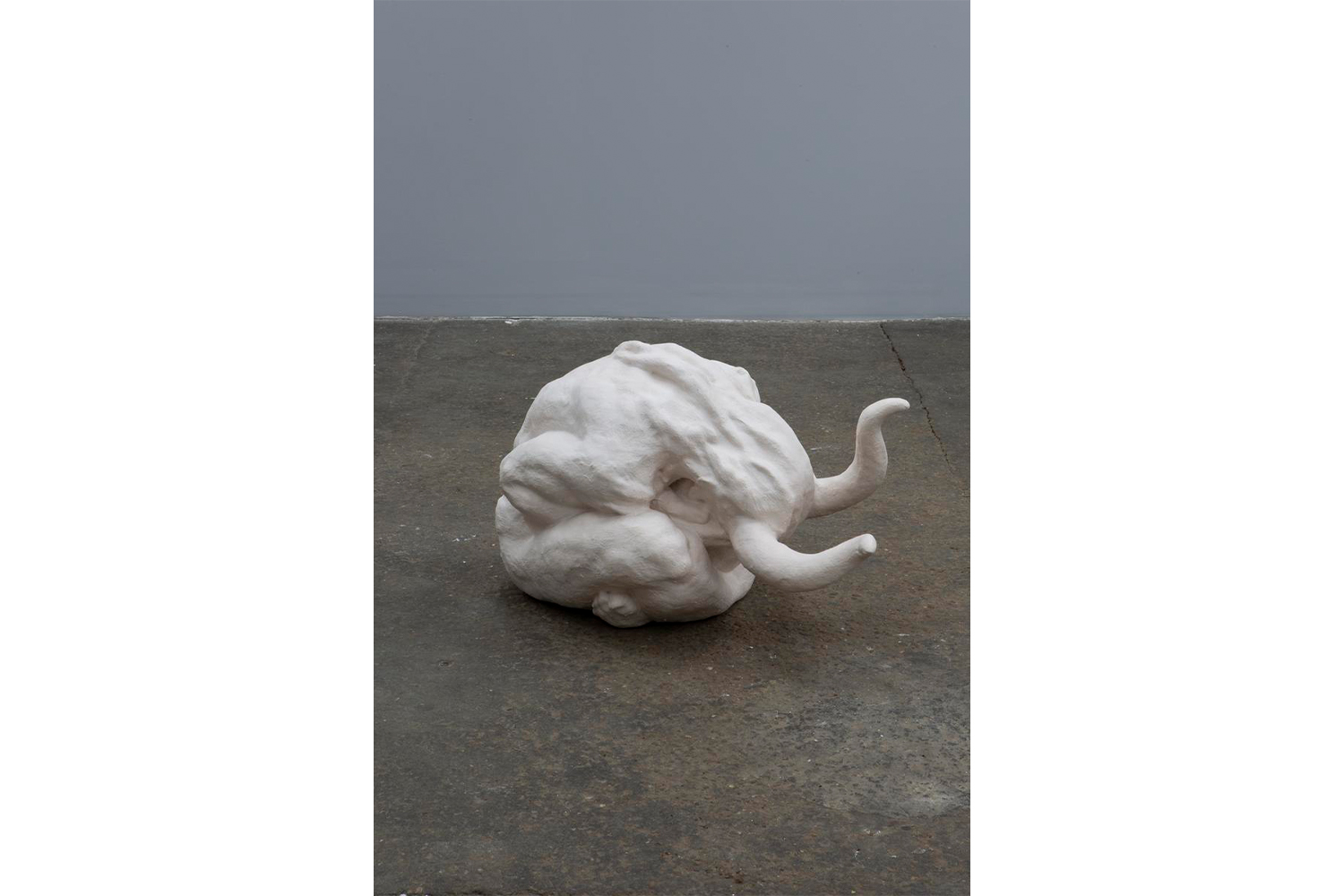

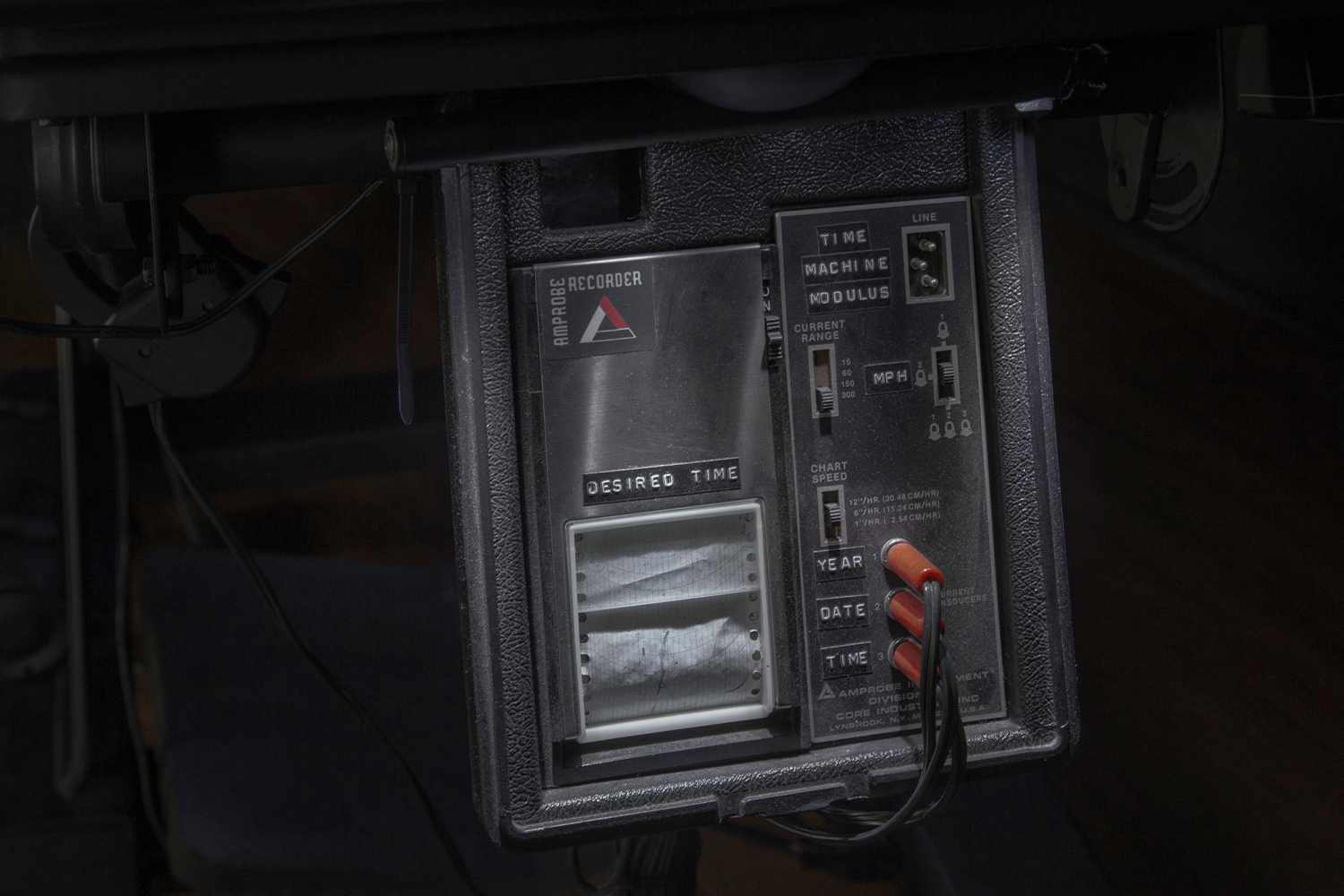

This piece [The clock tower strikes three times… (2022)] is when Hypnos first appeared in work in the exhibition “The Temple of Sleep” at Chapter NY. Much of the thinking of rewriting mythology is also breaking the mold of how a character can exist. This scene hints that Hypnos is both half human and half machine. In my mind, that’s sometimes what sleep means to me. Hypnos, the god of sleep, withholds the divine power of all living organisms — who, of course, is also a time machine. An ancient odometer for measuring travel distance is in the middle of his torso.

This is the first time machine I made before Hypnos; it was cool to look back to see how this machine developed from having humans seated on it to fully merging into a humanoid from itself. The original time machine was a reading machine; you read to activate the machine, and you read to travel through time.

I am fascinated by the element of time, how we determine it, measure it, weigh it, and yet also hold such immense awe for its malleable nature. The early Roman calendar in the 700s B.C.E. was borrowed from the Greeks. The calendar consisted of ten months, a year totaling 304 days. The year starts in March. The ten months were named Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. The last six names were taken from the words for five, six, seven, eight, nine, and ten. While pondering the title of this piece, I was looking at the calendar, thinking about why October, meaning eight, is placed in the tenth month of the year. I later learned about the old Roman calendar and thought about how it would be if the months marked winter never existed (January and February). Then what does each month mean to us in relation to the season? When a month is thicker and longer. Will October still feel like autumn? And thinking about how to mark a personal anecdote within all the contemplations. Like adding a new lexicon in a community of mind, it gradually grows into a development of shared symbols, together, the word and the work (the title and the visual).

TS: Describe your studio to me.

CL: It’s funny, I get this question a lot, especially from MFA students. The studio is a big issue, especially living in New York. Space is a very challenging thing. My initial response is always: Your studio is in your head. I spend most of my time thinking. And it is still true to some extent. But lately, my work has become quite labor intensive, and the physical space has become crucial. I have a studio space in Brooklyn where I make most of the larger physical work, and I have a home desk that I dedicate to work, where I do most of the sketches and writing. For now, I sculpt mainly with metal and wood; before, I’ve done silicone, fiberglass, and concrete. Right now, I’m focusing on structural and two-dimensional wood, with some metal engraving and lots of writing. That makes the notion of studio kind of tricky to gauge, but working half of the time at home and hanging with my cats is really rewarding to me.

TS: Who do you make work for?

CL: I think I can only make it for myself in so many ways. To put it out there to see whoever is willing to engage. It is an attempt to make a connection. A lot of the time, I have to measure my virtue in making work. If I finish a piece and feel emotionally rewarded, that is enough for me. When the work is out there in the world, I get excited about anticipating who has feedback. That is always an open surprise.

TS: What do you want to accomplish most as an artist?

CL: I can set some very shallow goals in terms of career markers, but for me, it really comes down to… how I can engineer myself. I want to be an artist who can translate my ideas fluently through the medium, the visual language, the materials, and the written language. I hope to be eloquent enough that the work can speak for itself. I’m someone who constantly struggles with language in many ways. English is my third language. I always struggle when I use one language more, and the other languages are slowly dying in me. As an artist, I wish to express my thoughts fluently. I want to write better, and to be more articulate in my expressions: either visual art, writing, or just my thinking. And hopefully, with all these goals aligning, I can provide myself with a sustainable way of living.

TS: Who are some of your favorite artists?

CL: This is almost a question you can’t answer. All my friends are artists. I’m influenced and enriched so much by my friends.

TS: What do you like about living in New York?

CL: I like living in New York for several reasons. In terms of health, this is the place where I feel I can get the most support as a trans person. In terms of emotional support, this is also the place I feel most at home — as a trans person, as an artist. I have a community of people that I can share values with without explaining where I’m coming from. That foundational understanding of values is something so profound. I really learned not to take it for granted. By leaving and coming back, I see that whatever we have [in New York] is precious. This is the place I’m going to call home. Financially, it’s very difficult. That’s a really big challenge. You weigh your pros and cons.

TS: Does your family understand your career?

CL: Yeah! I would say they are creative, while their careers still fit into the conventional. My father is in academia; he’s been the director of a university library for over thirty years. He surrounds himself with a broad range of things he’s interested in, from excessive antique collecting and cataloging to calligraphy, gardening, hiking, and traveling. Because of him, I’ve been babysat by libraries since I was a kid. Books are very comforting for me for that reason. My mother is in the beauty business, cosmetics. She’s one of the most creative people in our family regarding solutions. They’re fans of art and go to museums and movies over weekends. That’s how I was brought up.

TS: Which places do you want to visit next?

CL: It sounds cliché, but I want to visit Iceland, mainly for Roni Horn’s Library of Water. It’s the aspect of time, or how to measure the time in that system of natural history collection… I figure I could only understand it better by being there. And I want to visit my family in Taipei. I wanted to see how it feels to socialize as a man where I grew up. I have not traveled much since I transitioned, mainly due to COVID-19. This past winter was the first time I traveled after surgery. Traveling becomes such a nerve-racking thing to gauge about the crossing of the border and my own gender identity, how it mismatches on my passport, and how it feels internally. I was in Italy and London and Paris this past winter. The last time I was in these countries was before I transitioned. Traveling without personal history reminds me to exercise these muscles for new engagement. In a place without personal history, occasionally being thrown into socializing as a cis man was still very new, and I am still unpacking along the way.