A new generation of artists is exploring the intrinsic qualities of materials “informed” by the activities of humanity, and bearing its memories. Today, the most common principle of composition refers to the class of molecules called polymers(from Greek: poly“many” + meros“parts”) whose characteristics reside in a chemical agglutination of sometimes totally dissimilar elements. Liquid or solid, polymers consist of molecules linked by the “pooling” of “single” atoms, that is to say, a covalent bond, which may take the form of a collar, a constellation, or a complex network. Much like a polymer, an artwork can hold together the most heterogeneous elements, and so enables a process of subjectification: things indirectly reflect human reality, while humans appear to be caught in mechanical networks, reduced to the status of an exchangeable work force, or to the chemistry of their DNA. That is what I call molecular anthropology:it is a continuous, expanded anthropology, going beyond the human species as such. It considers humans as a mass divided in an infinite number of molecular cases. That definition of anthropology is the key notion for the 16th Istanbul Biennial, “The Seventh Continent.”

It is crucial to understand that today’s anthropology canno longer be centered on the human species: Back in the 1960s, Claude Lévi-Strauss saw its ultimate goal in the “dissolution” of the human figure. Acknowledging the end of the classical Western division between nature and culture, both anthropology and contemporary art embrace together animals, plants, stones, and machines: they reintegrate culture into nature. The phenomenon of the Anthropocene obviously contributed to this awareness, as the impact of human activities on nature generates an intertwined world, in which art has become an anthropology of global life, connecting humans and nonhumans. Through its research pattern (cross-pollenated anthropologies), this biennial is necessarily global: even more than “human diversity,” it has to enhance dialogue and mutual commentaries within a hybrid, creolizing, globalizing world that includes nonhumans.

Forms and Encounters: Coactivity

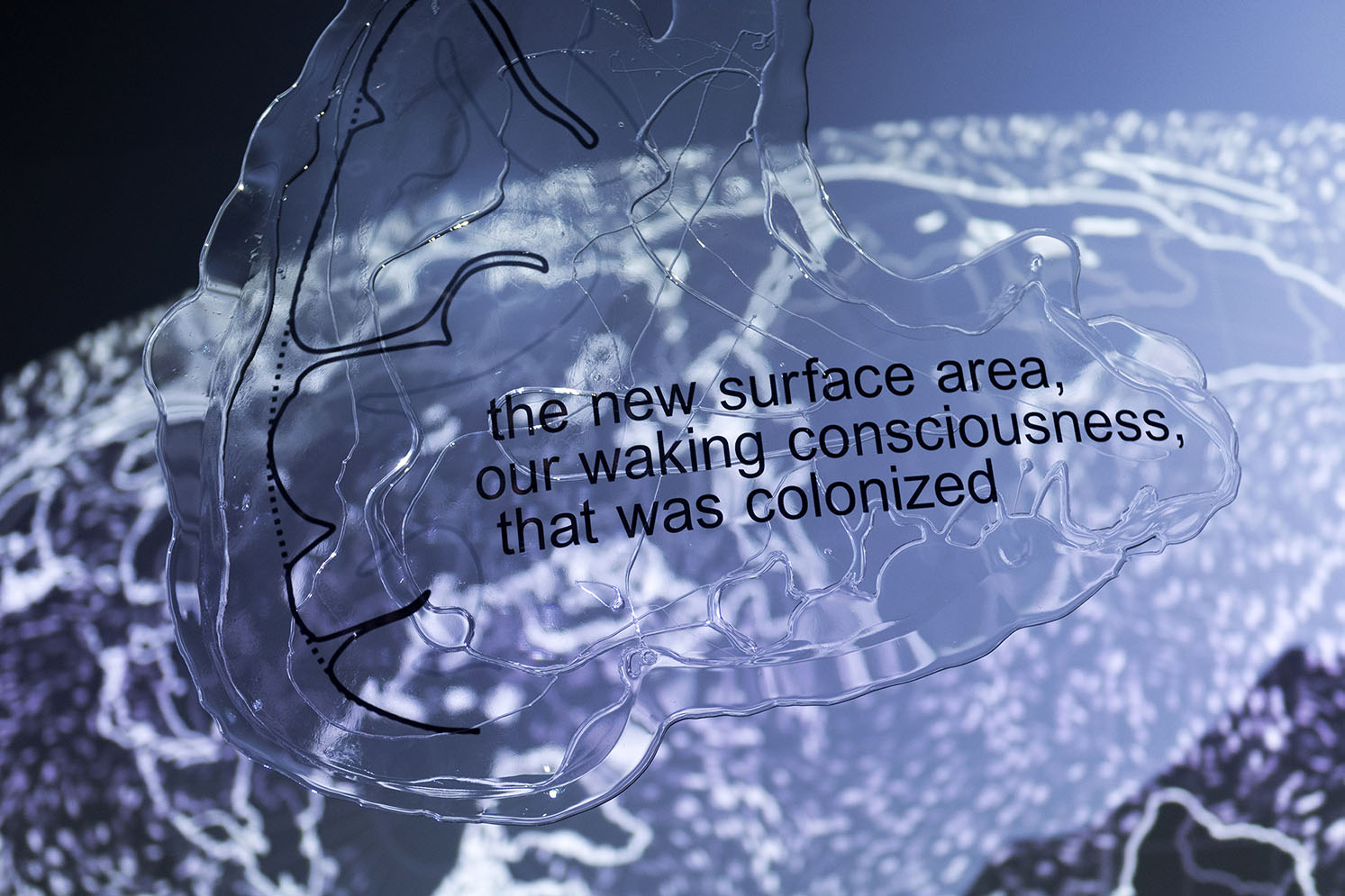

The Anthropocene is the space of a new promiscuity, a brutal bringing-together of all reigns and spheres in a space suddenly devoid of boundaries. This image of a universe without fixed boundaries (without skin) allows us to better understand the ambition of Pierre Huyghe: “Not to exhibit something to someone, but to exhibit someone to something.”In the Anthropocene, everything is being exposed, and the subject has lost its monopoly on the gaze. In 1964 Jacques Lacan proposed a strikingly similar thesis: the world is an “omnivoyeur,” he explained, but without reference to the notion of human consciousness: “I see only from one point, but in my existence I am looked at from all sides.”1He continued: “In our relation to things, in so far as this relation is constituted by way of vision, and ordered in the figures of representation, something slips, passes, is transmitted, from stage to stage, and is always to some degree eluded in it — that is what we call the gaze.”2This difference between vision and the gaze “in our relation to things” and “ordered in representation” could well be the key to allowing us to address the new status of the subjectin the art of today.

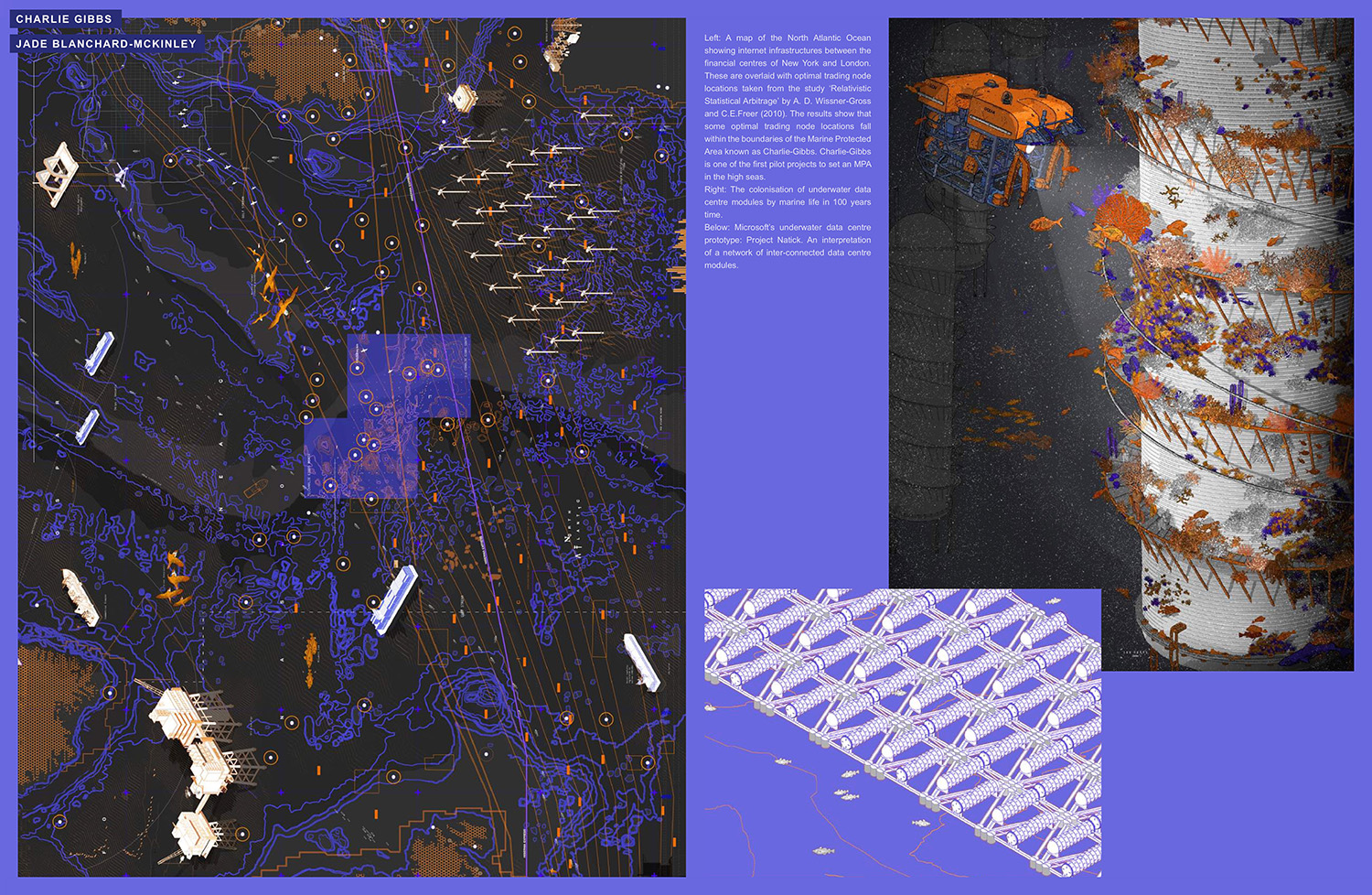

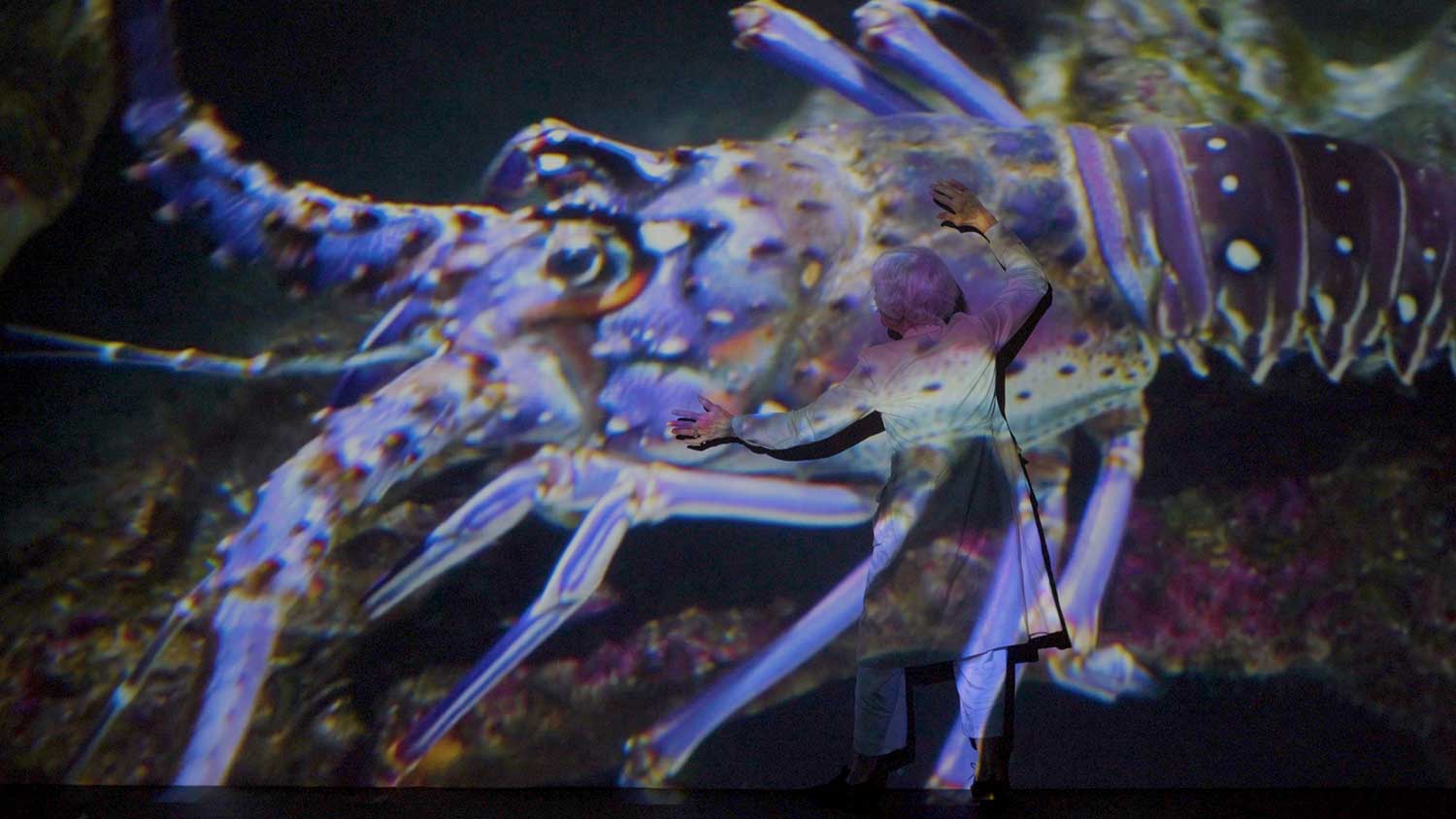

Contemporary art plays host to a productive entanglement between the human and nonhuman, a presentation of coactivityas such: indeed, the universe is made of multiple energies working side by side or together; the work of human beings is nourished by bacteria, other mammals, or the flow of nature. In many artworks, organic growth proceeds with the operation of software, and human relations are entangled with marketing channels or algorithms. All relations among different regimes of the living and the inert are in tension.

But today technology is seen as one sphere among others, or a “subject” supplementary to the human subject. What matters to the artist of our time are not the things in themselves, but the circuits that distribute and connect them. Art no longer occupies a dominant symbolic position: a trace among traces, an activity nourished by multiple parallel activities, an object within a world of objects. A work of art no longer enjoys a special status. In this space of coactivity, the term formtakes on new meanings. How should one define it, beyond the famous classifications of Roger Caillois, who proposed that forms should be distinguished by how they are brought into being — growth, accident, will,or molding? How should one describe the subset within which, in an exhibition, these different regimes interact? Katja Novitskova, author of PostInternet Survival Guide, writing in reference to Manuel De Landa, asserts: “The key word in any contemporary materialist philosophy (and I think the kind of animism to which I relate is a materialist animism) is morphogenesis—the birth of form. Whether it is the birth of the form of mountains, clouds, plants, animals, flames—everything has form, interesting forms, driven by self-organizing properties of matter.”3

Contemporary art takes into account all of these formations. Thus, it represents a gateway between the human and the nonhuman, a space where the binary opposition between subject and object dissolves and branches out in multiplicitous images: the reified speaking, the living petrified, illusions of life, illusions of the inert, biological maps redistributing constantly. And the mise-en-scène of this coactivity by artists today reinforces a notion that appeared in the 1990s: the primacy of the encounter over form. In other words, it is the idea that artistic practice is based on relationships rather than on objects and on a materialist view of contingency. On this point, we agree with speculative realism. Human beings are no more than one element among many in a wide area network, and we do not occupy its center: it is reality—that is to say, the relationship among all beings and things in coactivity— which occupies it.

But reality is often confused with either the world or with human society. In this regard, Alain Badiou cites Jean-Luc Nancy, for whom “the world is the expansion of existence beyond mere human reality. It is the application of the category of existence to something other than humanity. It is a meditation on animals, stones, the stars…”4The world and society end up merging under the effect of a growing and “intense proximity,” to use the title of an exhibition by Okwui Enwezor. When everything is close to everything, due to the acceleration of transport and the interaction between humans, animals, and plants, the problems of society are transposed to the whole world: another definition of the democracy objects. Alain Badiou does, however, accept the opposition between World and Society, defining the former as “the situation of the visible living.”But the pseudo-world in which we live, he continues, “erases the visibility of most human beings. It is not covered up, but removed. It is a protocol of exclusion from the visible, not of situation within the visible.”5What characterizes our time, according to Badiou, and is the true emblem of the contemporary democratic world, is the decline in the visibility of human beings at the expense of the object-product: in other words, the exact opposite of the observation made by speculative realism. The question that arises, for Badiou, in the field of politics is this exclusion, what he calls “invisibility,” that is to say, the refusal to make designations. But “there is no need to name,” he quips, “since we are all equal before goods.”6And the market is characterized by the equivalence of all objects within the mechanism of commerce. The capitalist world, says Badiou, is governed by the law of the object, “in the sense that [capitalism] claims that there is no… subjectivity unchained to objects” — that is, our passions and desires must translate into things.

But the domain of art is precisely that of exchange without common measure: all artistic experiences are unique. A work by Francis Bacon cannot be measured against one by Marcel Duchamp, outside of critical interpretation, because nothing quantifiable unites them. Except, precisely, when these works are found on the market, where prices differentiate them. Apart from this case, art is the refuge of the immeasurable: we cannot exchange an artistic experience, we can only share it. “What has never been looked at” is precisely the opposite of art, which postulates a priori the visibility of its productions. Moreover, they are received by a human consciousness that reflects upon the enrichment of an experience. Just as one cannot find a common measure between a rock and a human being, except that of their coexistence in a common biotope.

•••

One of the engines of economic globalization is the ideology of “growth,”i.e., the narrative that exponential growth is essential, according to the prevailing ideology, for the future of humanity. Or, as Jean-François Lyotard put it, “Development is not attached to an Idea, like that of the emancipation of reason and of human freedoms. It is reproduced by accelerating and extending itself according to its internal dynamic alone.”7Likewise, the “Great Acceleration” is capitalism’s process of naturalization: organic and universal, it is the natural law of the Anthropocene. Its main tool is the algorithm, on which the global economy is nowfounded. The only known limitation of industrial “development,” for Lyotard, resides in the life expectancy of the sun — “the only challenge objectively posed to development.”8

Since the 1990s, art has highlighted the social sphere and held inter-human relations, whether individual or social, convivial or antagonistic, as its domain of reference. The current critical fortune of speculative realism in the field of art appears to signal another acceleration: the evacuation process of humanity. Relational art has been criticized for its anthropocentrism, even its thinly veiled humanism, for considering humans as an aesthetic or political milieu, indeed, for extending its range invasively into the realms of objects, networks, nature, and machinery, in a manner now deemed by some as untenable or old-fashioned. It seems to me, on the contrary, that the major political issue of the twenty-first century is precisely the return of humanity, to all the areas we have vacated: computerized finance, delivered in mechanically regulated markets, and primarily in policies fixed on the sole objective of profit — that is to say, the quantifiable world. A return not to the center— for nothing can be the center of a coactive universe, of multiple coexistences in a shared ecosystem— but to the heart of these activities that are no longer “human” in name.