It’s a new decade. One continent just burned and another is sure to. We are either at the precipice of another war or already in it. I hear the economy has never been better, and you, me, and everyone we know are tangled waist-deep in a global web of human suffering. Surgically curated by Søren Grammel, one of his last efforts at the Kunstmuseum, “Circular Flow” broadly examines the intense real-life impact of centuries of ongoing global inequality. It is stuffed and loaded with known quantities and discoveries, commissions and works from the museum’s collection.

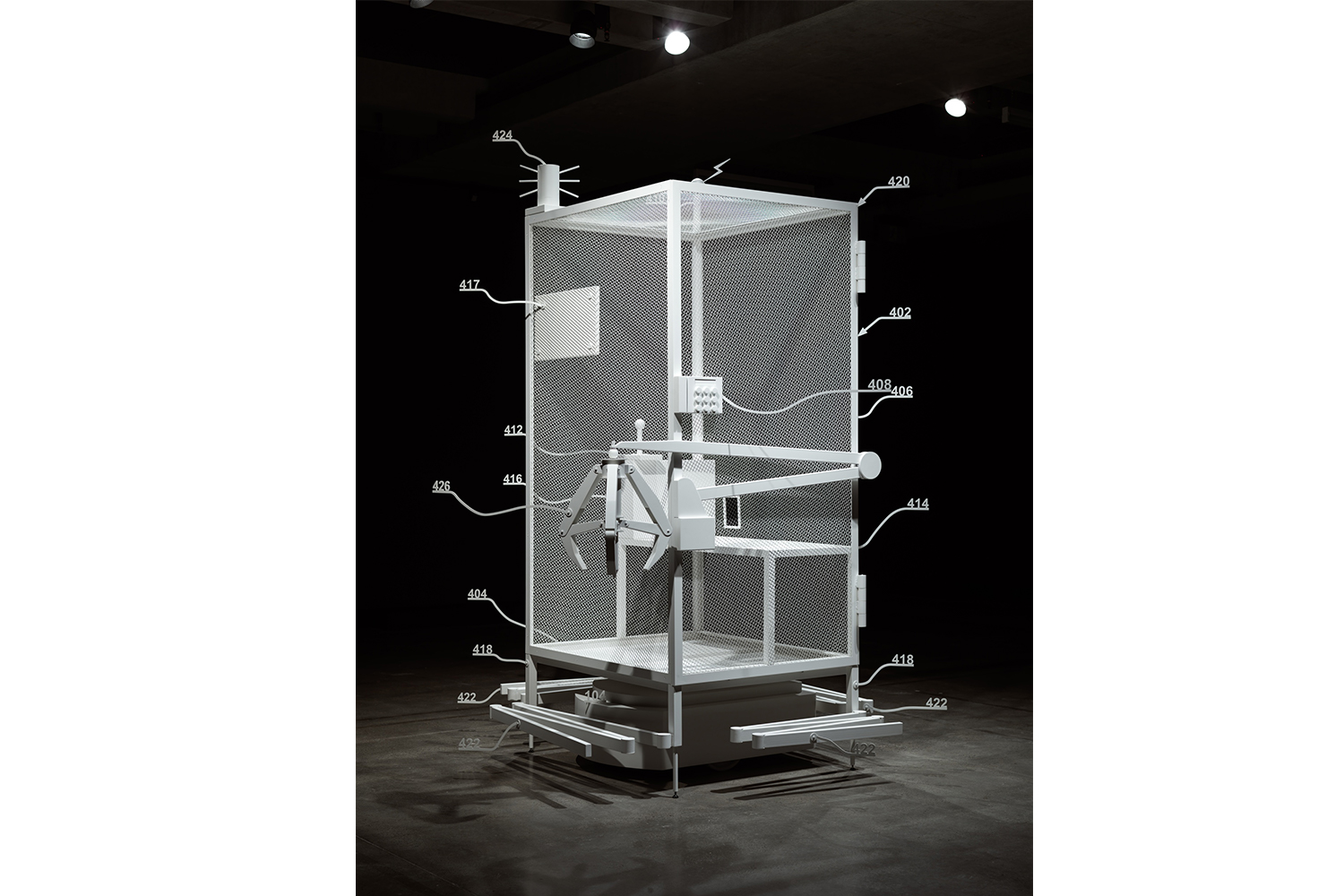

It is a show for which hours of viewing and return visits are vital. Every film is necessary and presented in its own environment. Richard Mosse’s Grid (Moria) (2016–17) transforms views of an immigrant detention center into a minimal sculpture; Ursula Biemann’s Remote Sensing (2001) tracks the global routes of sex trafficking; and Lisa Rave’s Europium (2014) explores the devastating strip mining of the Pacific Ocean floor in the quest for the rare-earth metal of the same name, used in flat-screen displays. Nearby hang a range of Gauguin woodcuts, reminding viewers that exploitation of that geographic area is nothing new.

Wang Bing’s 15 Hours (2017), a single shot within a Chinese sweatshop, is alternatingly appalling, meditative, and startling as the mind focuses on the lived implications, the repetitive fabrication, and the human social bonds that exist within. Lasting as long as a single shift in the factory, the film must be watched to completion over two full days at the museum: exhibitable inequality in action.

Grammel has thoughtfully paired new and older works. Frans Post’s Brazilian Landscape (1658), created at the height of the transatlantic triangle trade, is hung near Cameron Rowland’s Tax Return (2018), a historic listing of slaves as assets. Rowland’s insistence on using his own wall text narrows it to the hyperlocal of the southern United States, but the pairing opens the work to the world.

Andreas Siekmann and Alice Creischer’s room-spanning installation takes the root of all inequality, man’s early insistence on agriculture, and traces its many talons today. Large panels abstractly illustrate the monopolization of seeds, the protest suicides of displaced Indian farmers, and the currents of corporate money that sponsor even this museum.

Every awful concern is not only checked but is connected to the next. It is an ambitious show, and hardly didactic. It proves that when we talk about colonialism we are thinking too small. Financial inequality, climate change, and human rights abuses are not specific to our time, but our ability to perceive a global network is. It’s this perspective that shifts the exhibition away from the merely grim. Far from catastrophe porn there lies possible impact. Opening this show right before Christmas was wise; there’s never a poison gift quite like the present.