The risk of partial reception or the flattening of content in thematic, muscular exhibitions like the one presented by the Centre d’Art Contemporain is a constant. The risk is the biennial effect — an exhibition that is not particularly memorable or one that, due to a lack of thematic cohesion, has no impact on the history of curating nor any resonance with the present.

After his previous study of language — “Writing by Drawing: When Language Seeks Its Other,” developed in collaboration with the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, in 2020 — Andrea Bellini’s vision expands further by choosing another primal theme, that of metamorphosis in “Chrysalis: The Butterfly Dream.”

Articulated on all floors of the building, this discourse on changeability, on the inherently fluid, ephemeral, and unstable, is reflected in a canny juxtaposition of works — from Marguerite Brunat-Provins to Grisélidis Réal’s sophisticated ballpoint pen works on paper, to Guo Fengyi and Genesis Breyer P-Orridge — that is anything but predictable, and that seems incapable of being exhausted. Indeed, the strength of this group exhibition (which does seem to have secret biennial aspirations) lies in the fluidity of the languages and depth of research presented. The metamorphosis here is dissected and unpacked without limiting itself to its more physical-material manifestations, typically understood as a dualism expressed via experimentation between organic and inorganic matter — an obvious and immediate angle that we find in Jenna Sutela’s artificial breast HMO Nutrix (2022), in Agnes Questionmark’s ceramics Rachel Rose’s glass and rocks, Mathilde Rosier’s mystical forms, or Marianna Simnett’s Blue Moon (2022), in which the artist’s glitchy figure embodies a dysfunctional Athena with a deformed body.

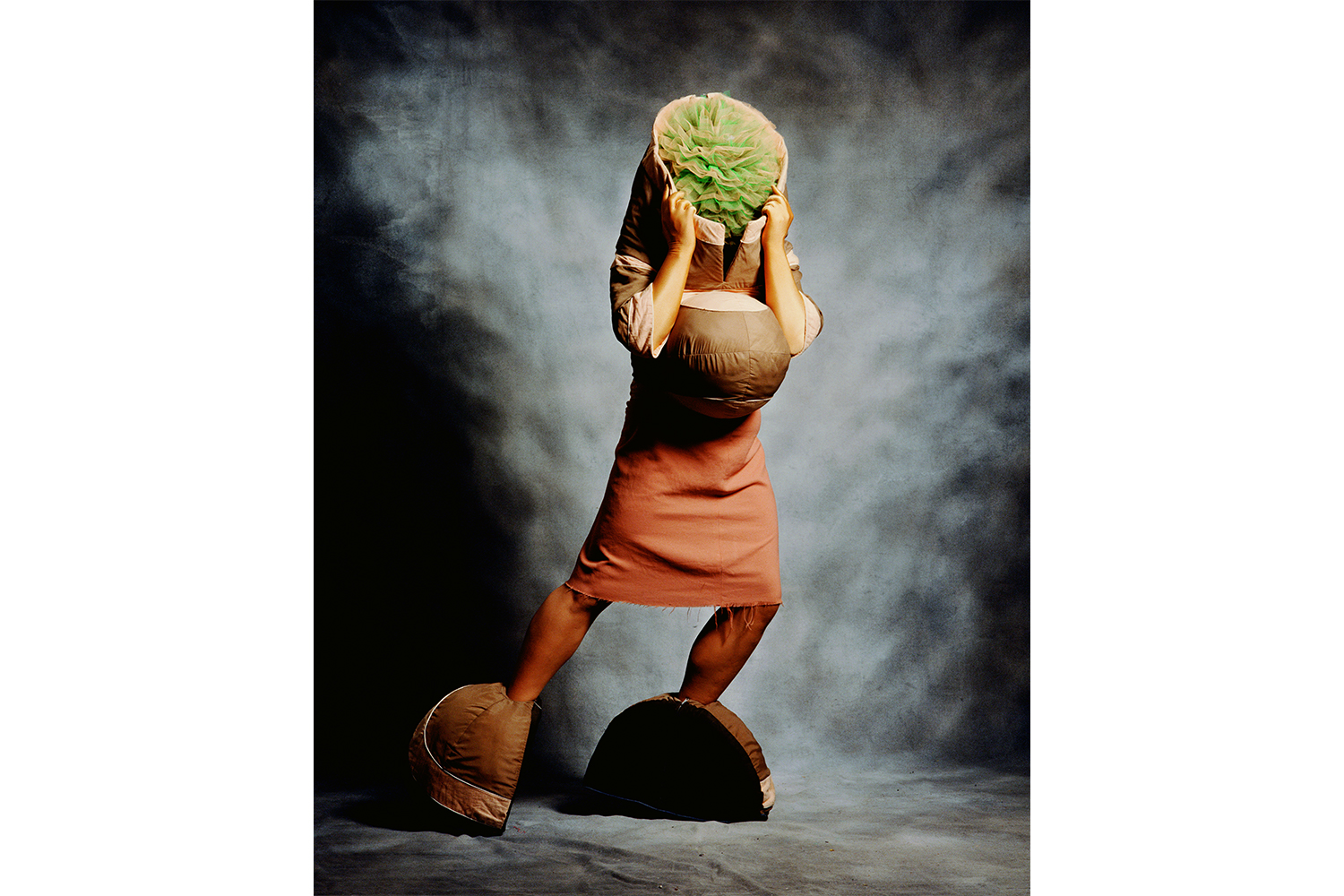

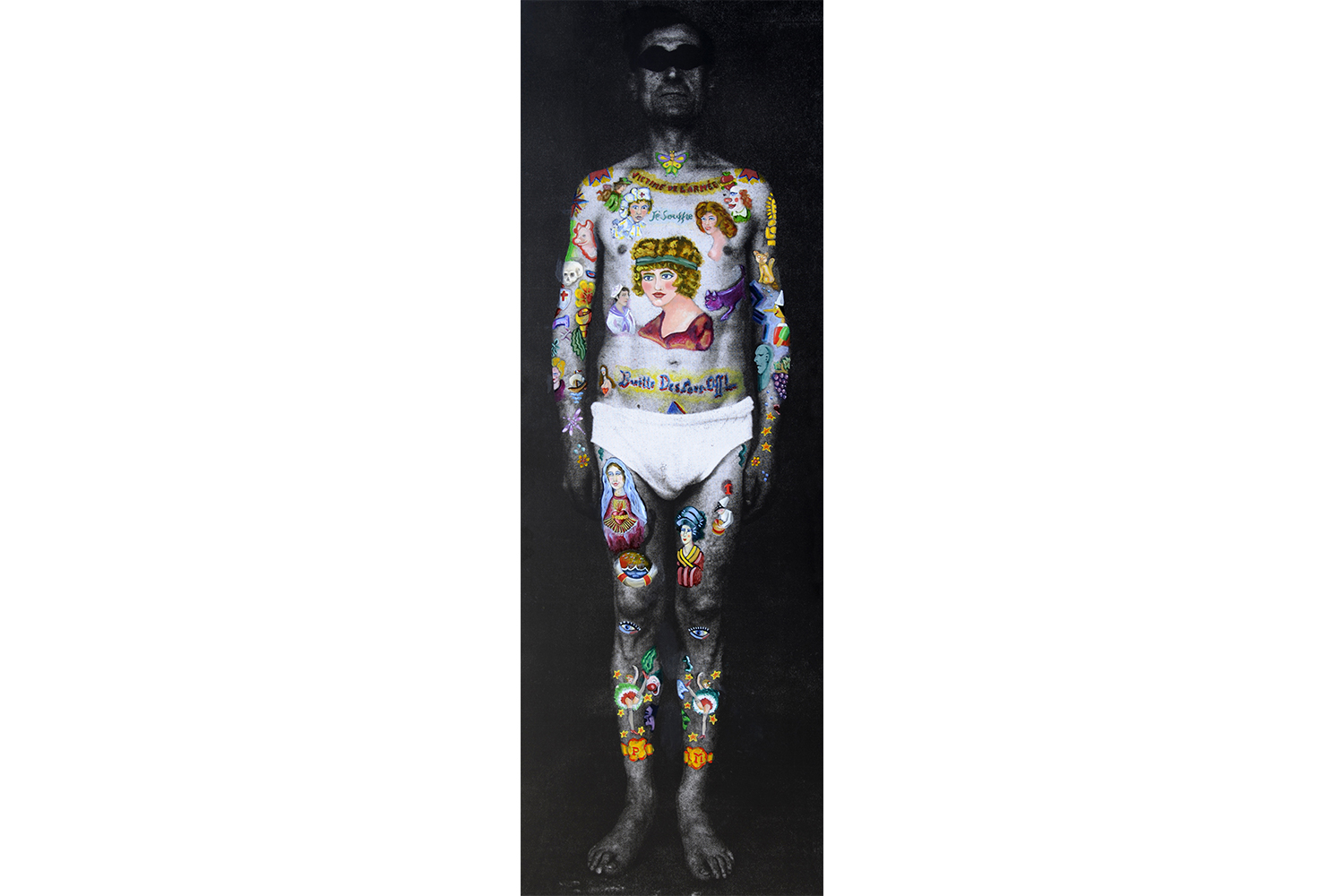

“Chrysalis” is, above all, an occasion to look at themes related to identity and gender as phenomena of constant renegotiation for a self in transformation: for example the unexpected diptych Dietro Front (2011) by Plinio Martelli — one of the flash points of this exhibition, at least for me — in which his obsession with the tattooed body as a primordial impulse leads him to a very personal vision of painting — the artist-painter who traces in the body itself the possibility of renewing the face, of changing the skin. Martelli engages in a sensitive dialogue with Luigi Ontani, but also with Leigh Bowery, who uses his image as a vehicle, as in the series of photographs taken by Fergus Greer between 1989 and 1994, which document the artist’s transformations.

The continuous change of status, grammar, and research makes any association of personalities, so distant in terms of geography, background, and language, feel dubious at some points, yet at the same time this is what makes the exhibition’s path seem so “proper” and unpredictable.

Ontani’s works, which return at different moments in the articulation of the exhibition, function almost as spectral presences or warnings. We see this too in Pierre Molinier’s photographs, or in Eleni Christodoulou’s Not Yet Titled (2022), or again in Juliana Huxtable’s two digital avatars with their furry aesthetic (Untitled, 2019), in a continuous slippage between species, genres, and worlds; in the oils on canvas from Kaari Upson’s “Kiss Paintings” series (2009–15); as well as in the wax cast of Lynn Hershman Leeson’s face, titled Breathing Machine IV (1968), from the “Breathing Machines” series.

The connections given here are partly suggested by the exhibition’s itinerary and partly the result of personal digressions, activations of the gaze, and mnemonic associations. It is precisely this exercise that, beyond matters of taste, makes for an effective exhibition. To keep playing with the works in one’s head, to think back to Anna Zemánková’s drawings and Sergio Sarri’s acrylics that cohabit the same existential sphere. As if to give oneself ever- new possibilities of existence.