Valentina Sansone: In 1971 you presented a performance that consisted of being shot (Shoot). Later on you claimed that you did it in order to “be taken seriously.” As an artist, what did the notion of ‘limits’ represent for you at that time and what do they represent for you today?

Chris Burden: ‘Limits’ is a relative term.

Like beauty, it is often in the eye of the beholder. When I did the performance Shoot in 1971, I knew I was making art in a way that few others were. But, you must know that in order to do Shoot, I had to convince myself that the marksman would only scratch my arm with the bullet and that one drop of blood would roll down my arm. The question for myself would have been, “Have I been shot?” Obviously, the wound was more serious than that, but as you can see, I was trying to find where the edge was. I have always had an active imagination and I am not sure that my idea of limits is any different today than it was in 1971.

Sonia Campagnola: When you think back to the early ’70s and your first actions and performances putting your own life in danger, what is your take on them now that your work moved elsewhere and the surrounding world changed?

CB: First, my early actions and performances were not suicidal, and did not put my life in danger. Today, I am proud of those early works. They were important in my artistic development and they have become a part of art history. However, I no longer have an interest in doing performances.

VS: During the performance Jaizu in Newport Beach in 1972, you sat immobile in a chair wearing dark glasses. Visitors thought that you were looking at them and they refused to speak. Actually, your lenses were painted black inside so that you couldn’t see. After the action, you said that some people were aggressive and that a few of them even had hysterical reactions.

Most of your performances feed on rage and physical pain. Could you speak about these topics in relation to your work?

CB: No rage and very little physical pain.

VS: Early in the ’70s you often railed against the Vietnam conflict. Do you think artists coming from countries that have been under a totalitarian government are more likely to realize extreme actions and performances dealing with strong political issues? Do you see a connection between these artists’ practices and performance practices in ’70s?

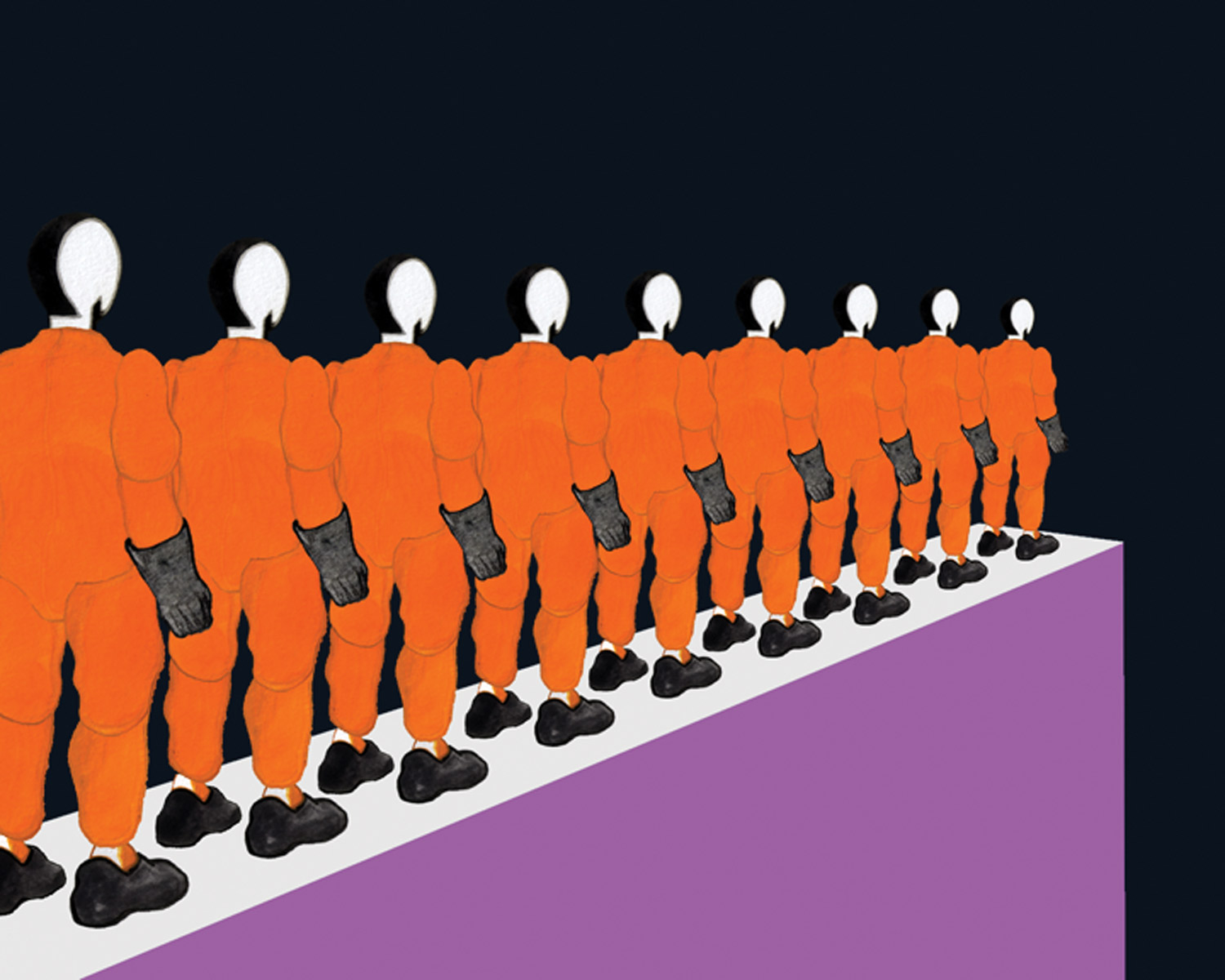

CB: Artists in totalitarian societies are less likely to be able to realize extreme actions because they are usually jailed, and/or executed.

VS: In an interview in 1975 you defined art as “a free spot in society, where you can do anything.” “Anything,” you would add, “that society will let you do.” Could you give any examples of how social conditioning has restricted your work?

CB: There are always two sides to a coin.

Society is usually fixated on only one side of the coin. For example, being shot is considered by society to be a bad thing and to be avoided at all costs. Sometimes it is of some interest to flip the coin and face the dragon head-on.

VS: A Tale of Two Cities (1981) represents a metaphor of war’s enormity. Five thousand toys created a large-scale installation where the act of repetition assumes a freaky atmosphere. Where does this obsession come from?

CB: A Tale of Two Cities represents two make-believe city-states at war with each other. The big city is invading the small city. In this mythic world, the weapons for both cities are bought from a separate arms-producing state. Thus, A Tale of Two Cities is actually a model of the modern world. I purchased all the toys in A Tale of Two Cities, including the war toys, at different periods of my life. I still collect toys. Toys are a reflection of society. They are the tools that society uses to teach and enculturate children into the adult world. Toys are not innocent.

VS: The Big Wheel (1979) was a system that linked a big antique metal flywheel to a motorcycle. What My Dad Gave Me (2008) is a 20-meter-high Erector Set skyscraper that you and a team of assistants built in California and installed in one evening at New York’s Rockefeller Center in June last year.

You have always found in engineering a way to overcome the most overwhelming phenomena: gravity, distance, weight and water. Are you still working on the idea of limits?

CB: Yes, I am constantly searching for the edge.

VS: In Topanga Canyon there is an installation of vintage lamps that you collected in the last few years. Does your work also include research on architecture besides sculpture?

CB: I collected the vintage streetlights you refer to over a period of nine years. They were initially installed around my studio in Topanga Canyon, and in 2008 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art purchased them. They are now at LACMA and arranged in a grid that recalls an ancient temple. They have become a building with a roof of light. Yes, I do have an interest in architecture and the space that surrounds us. It has always played a role in my art making.

VS: A few weeks ago the opening of your solo show at Beverly Hills’ Gagosian was postponed. The gold bullion originally purchased for the show by the gallery was frozen by the federal authorities [according to Reuters, the gold was sold by a billionaire accused of financial fraud]. How was this planned exhibition originally conceived?

CB: My planned show at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills was titled “One Ton, One Kilo.” In the gallery’s ground floor main exhibition space, I planned on exhibiting a restored 1964 Ford one-ton crane truck. I had a 78.8 centimeter cube fabricated out of cast iron with 1 TON incised on all 4 sides. The cube was hung from the crane at chest level. It was the first thing you saw when you entered the gallery. My 1985 sculpture Tower of Power was to be displayed in the gallery’s small exhibition space upstairs. Tower of Power consists of a small pyramid fabricated from 100 one-kilo bars of 24K gold. No press releases or publicity announced either work. Thus, after seeing one ton downstairs, viewers would logically have expected to see 1 kilo upstairs. In fact, it involved 100 kilos. The exhibition was about weights, measures and value. The new work, One Ton Crane Truck (2009), seemed a good partner for the older work of Tower of Power.

SC: Thinking of your planned exhibition “One Ton, One Kilo”: what is a good system to understand and price the value (cultural and commercial) of art? For you, what’s a good, healthy relationship with money and with the commercialization of your work? Is there any discrepancy between the commercial value and the cultural value?

CB: There is no relationship between commercial value and cultural value.

VS: Last May you realized one site-specific Beam Drop in Antwerp. This is maybe the artwork that best represents your recent work. Could you tell us a bit more about it?

CB: Beam Drop is a sculpture produced by dropping from a height of 40 meters, with the assist of a crane, 70 to 100 steel I-beams of varying length and width, into an 11-meter-square pit of wet concrete. This process of dropping the beams into wet concrete takes an entire day. The finished sculpture becomes a petrifaction of a cataclysmic event, much like Pompeii. You must remember the I-beams are the building blocks of all corporate architecture, and as such, are to be taken seriously. Steel workers are never supposed to drop I-beams. Jackson Pollock used paint in an abstract expressionist manner. I am using heavy steel beams in an abstract expressionistic manner.

SC: Which is the most important work you think you have accomplished in your life so far?

CB: The idea that art is important, and that I continue to both believe in it and produce it.

SC: You saw and participated in almost four decades of art history. What you think art gained in recent years and what has it lost?

CB: Art does not gain or lose. It is a process.

SC: What influence has the particular culture of Los Angeles and the artists that inhabit it had on your way of thinking and working?

CB: Los Angeles is an ever changing and vast ocean of people and ideas. Even though I have lived here for 40 plus years, the pace of change and the resources available never cease to amaze and fascinate me.

SC: How would you describe your daily practice and work routine?

CB: I live in Topanga Canyon, which is a part of the megalopolis of Los Angeles. My studio is next door to my house and I employ a large staff. I walk from home to studio every morning. I check on the various projects that are under construction and I work in my office answering correspondence. In the evening, I walk back to my home.