In the last few years Cerith Wyn Evans has become a point of reference in London’s artworld, an unavoidable entryway to its backyards. His practice has inspired many artists emerging in the latest generation, creating a small group of conceptual followers who have borrowed his sophisticated aptitude for making connections through evocation and encryption. His conversations and guidance to fellow practitioners as well as cultural producers represent an invisible architecture in progress that secretly shapes the cultural landscape of London.

Francesco Manacorda: Let’s start talking about your upcoming show at the ICA in London.

Cerith Wyn Evans: Well, I approached this exhibition from several different perspectives. First of all, this show is a way to return to the ICA, which is an institution that I have been involved with casually and more intimately over the years for a long time.

FM: This is since the famous Marcel Broodthaers show that shaped your understanding of contemporary art…

CWE: Yes. “Décor: A Conquest by Marcel Broodthaers” was one of Marcel Broodthaers’ very last shows while he was still alive. It was at the ICA in 1975. As a young man I visited London and I saw a work by a contemporary artist of an ensemble — at that time, one wouldn’t have used the word ‘installation,’ but a group of works installed in the rooms upstairs in the ICA. It had an enormous impact on me. I was overwhelmed by something that I hadn’t really encountered before, a kind of staging, a mise-en-scène. The sense of being unsettled in terms of one’s own history or in terms of one’s own narrative was completely captivating to me. It was an epiphany when I walked into that room. It was like walking into a movie — a little bit that feeling of walking on stage and actually finding yourself removed from yourself. The piece acted like some kind of machine where you were able to reflect on your own condition in the space. There were curious objects, halfway between a museum whose artifacts you didn’t really quite understand and something like a stage set.

FM: A sort of incongruent constellation…

CWE: Exactly, with the beach furniture and the guns leaning against the wall, and cannons pointing out the window at the Big Ben. I became very agitated by it and it stayed with me.

FM: So this exhibition is also a retrospective of your relationship with the institution?

CWE: Yes it is. There have been many instances where I have been part of things that have happened there since then. The first time I showed work at the ICA, there were screenings of films that I had made when I had graduated from St. Martins School of Art here in London.

FM: This was in the exhibition conceived by Derek Jarman “A Certain Sensibility” in 1981.

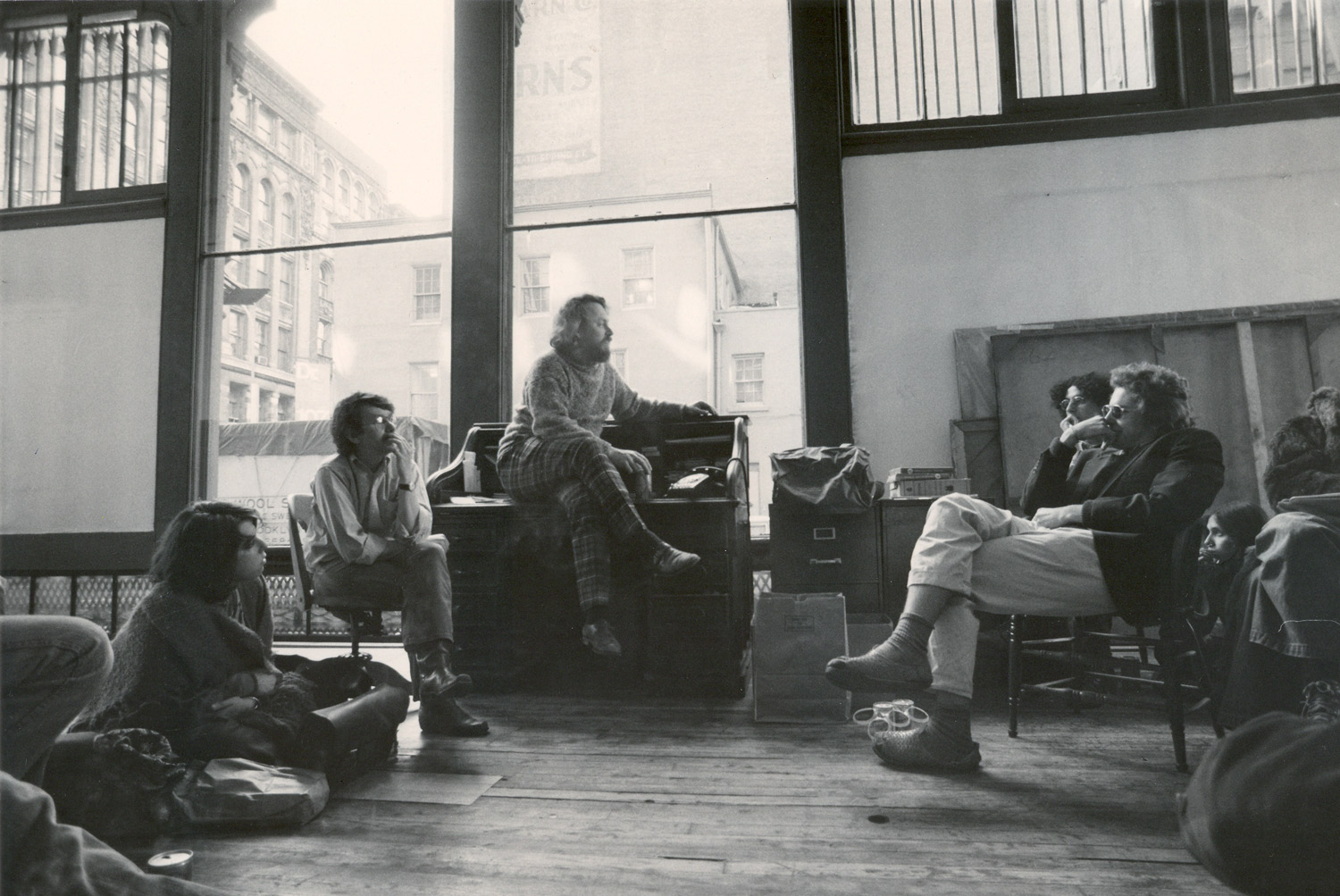

CWE: Derek was a neighbor of St. Martin’s School of Art, so it was even by proximity as neighbors that we met.

FM: Did he curate that exhibition?

CWE: Not curated exactly… The first exhibition consisted of myself and John Maybury. We were both graduating in the same year and we were both independently unbeknownst to each other making short experimental Super 8 films that had really rather a lot in common. The ICA cinemateque at that time had just opened and Derek Jarman felt he was able to suggest these two students. We screened our Super 8 films; there were never any prints or negatives. We just showed the originals, and so if anything burned or snapped it was just gone forever. So these things were quite close to performance events in a way, for which we had a month long residency at the ICA cinemateque with screenings every evening.

FM: Would you produce new work every day?

CWE: Yes, work would be produced for the screenings. At the time it didn’t feel a very radical thing to do. It just seemed so boring showing the same film the whole time so… let’s make another one, and next Wednesday we’d have just got it back from being in the post from Kodak. And then you would show it, and you’d put on another soundtrack on cassette tape. So you just more or less improvised based around three or four things.

FM: That means the film night became a sort of stage?

CWE: Yes, very much so. We fooled around with that quite a lot. We perfumed the cinema, so there’d be different smells for different films, and different music. We had interval music when people came in and before they sat down. I can remember one week playing all the work of the second Viennese schools. So you had Schönberg, Webern and Berg; this dodecaphonic music would be played and then, when the film would start, you would put on some really thick lush romantic pop music. There’d be free cigarettes for the audience, and there would be fruits and alcohol out. There’d be a drinks trolley at the front, so people could help themselves. There was this kind of performance aspect which became about behaving in a different way in the cinema, and around it.

FM: It’s interesting that you drew together different elements and activated the cinema in a similar way to how Broodthaers activated the space in his exhibition. Do you see this as consistent with your current practice?

CWE: Yes, I suppose so. If you were to think about the associative approach. This return to the ICA is a kind of recognition of all of that, an attempt to address that recognition as the subject of the exhibition. The title of the exhibition to that extent is rather telling. In this particular case I wanted to take a risk in making a title somehow over determined. The title is “Take my eyes and through them see you” and it speaks of the notion of trying to extend the subjective perception into interrogating the phenomenological boundaries between the visible and the invisible. For me it means looking at the often misunderstood notion of the viewer completing the work of Duchamp.

FM: Do you aim to reverse it and encourage the work to complete the visitor?

CWE: In a sense, yes. To a certain extent there’s a sort of mirror phase. There’s a sense of a doubling or a splitting whereby not only do we look at monocular and binocular perceptual models, we also look at what those might imply in terms of metaphorical code.

FM: Is it all new works?

CWE: Yes it is. What I’m attempting to do is to empty out the ICA of absolutely everything more or less. I was never very happy with that downstairs gallery. You come in off The Mall and you have to take some steps down into that space, you’re half buried in that space. It occurred to me that there is a wall that’s been up against the windows on the mall, which has been up there since ever. I thought it would really be good to take a leaf out of Gordon Matta-Clark’s book, and remove the wall, exposing the window’s view onto The Mall. So that room will be a completely empty room with a few windows onto The Mall. What you will be able to do is to sit down in an absolutely pristine and white and empty room. Behind the wall I imagine (it hasn’t been done yet ) there’s going to be a hundred years of cobwebs and dust and skeletons.

FM: Which you’re going to leave there…?

CWE: Yes, we’re trying to make quite a clean cut out of it and make that cut the window in a sense.

FM: It’s nearly an archaeological process?

CWE: It’s kind of bound up in that; the impulse is to remove something and expose the view that is beyond. It may not be apparent to the people who are walking along The Mall that they are the view, the exhibition. There’s the idea of opening up the apertures that frame the life that’s happening on the street.

FM: So is your intention to turn the gallery itself into an optical machine, perhaps a metaphorical film camera?

CWE: It does to a certain extent. It also becomes a kind of real live movie theatre. You get this interruption which again relates to Broodthaers, who made this amazingly beautiful film, The Battle of Waterloo, which was shot in the exact same position from the window upstairs. Certainly there’s an attempt to revisit and recall a view from something similar to that perspective. Upstairs, in one room I’m putting on shutters on the outside of the windows; there’ll be nothing inside the space at all apart from a computer screen which will relay to the shutters reading in Morse code a text. So the view is fragmented and encoded between the slats. That view includes the Horse Guards Parade, the Cabinet War Rooms, Downing Street, Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament. It’s just about the only window in London that gives you that particular view and it will be partly occluded by the shutters that read a text really about the act of viewing amongst other things.

FM: Viewing’s related to filming and cinema as well…

CWE: Exactly. It’s related to the idea of things being played out in real time.

FM: It’s as if the viewer became the film, the celluloid on which light is impressed…

CWE: It’s a little like that. I’m very interested in playing those games that interrogate that kind of interstitial space. There is a sense of flow, a sense of movement, a sense of pourousness, an oscillation from one category into another.

FM: It’s also very interesting that you are using London, as the support or medium to communicate the text, because it’s physically becoming the element encoded in the Morse…

CWE: Yes, when London is on the letter is being spoken. When the view is visible the letter is being read. The idea is to appropriate the view. The most recent example of that, prior to this ICA show, was finding a wall on the roof of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris that you could only see from a fire escape door. It consisted of the title of the show working as subtitle to the view: “In which something happens all over again for the very first time.” To me this was about a paradoxical return. It was a white glazed brick wall with this sentence in neon sign, written in Helvetica Light, which is very close to the typeface used to subtitle foreign films — behind this subtitle the Eiffel tower, the symbol of Paris. The central notion here is framing, the idea of a frame which is related to language, to parenthesis, to brackets.

FM: The frame cuts across art history, painting and cinema? And I’d say cinema in particular, when you add to it subtitles…

CWE: Sure, and what happens when the frame begins to shift or the frame begins to move; or when it’s possible to recognize a predominant frame and then willfully shoot the frame in order to include something that was perhaps improperly placed within the frame. I think we can talk in symbolic imaginary terms about what a frame constitutes; frames that aren’t necessarily views onto something.

FM: Are these new works using architecture as a ‘found frame’?

CWE: Well, it would nice to be able to move the ICA’s windows… By implication then, if the frame is there, it might be possible to actually dislocate the frame from its view. So that there isn’t a tyranny between the fixed frame and its given view; that it might actually be possible to imagine cutting the moorings between the index and the register.