Hans Ulrich Obrist: What were the trends in the Academy?

Carla Accardi: The Academy’s trends focused on Italian art, while at the same time, in Europe, there existed people like Kandinsky, Klee and Mondrian. During that period, Italy was a little self-contained, even though there had been Balla and the Futurists, who were extraordinary. Yet by that time, which was after the war, the Futurists were part of the past. Back then, everything was tied to local experience, in line with the “rappel à l’ordre” kind… do you know this reactionary European movement? Since I was disappointed in the Academy, I would go and copy Beato Angelico’s work in the Convent of San Marco, in the Academy’s square. Or I would go on the Arno. Then Sanfilippo mentioned he had some really interesting friends in Rome…

HUO: And this all happened in ’46?

CA: Yes. Back then I wrote a letter to my parents letting them know I did not want to study any longer, and I came to Rome. There I met Turcato, Consagra, Perilli and Dorazio.

HUO: So there was a connection among different generations?

CA: Yes, but Severini only came on a visit every now and then, because he lived in Paris. Prampolini also hung out with the younger crowd. We thought we should put together a group to keep up with European trends. In ’47, we formed this group.

HUO: You mentioned Art Club, an important place for you. Did you used to hang out there before the group came together?

CA: No, it happened simultaneously. At the Art Club, several artists from the time came together.

HUO: Did you also meet in the artists’ studios?

CA: Yes, particularly at Consagra’s studio. Even though we were very young, once we printed and published Forma Uno and presented a group exhibition, we generated a lot of interest in Rome. We were the first group after the war. After us came Origine, and the Group of Eight. During those years, I also met Colla. We would often go to his studio, where we also had an exhibition in homage to Leonardo da Vinci.

HUO: An exhibit of your group’s work?

CA: No, not only, there were also those from the group Origine.

HUO: So the group’s boundaries were flexible?

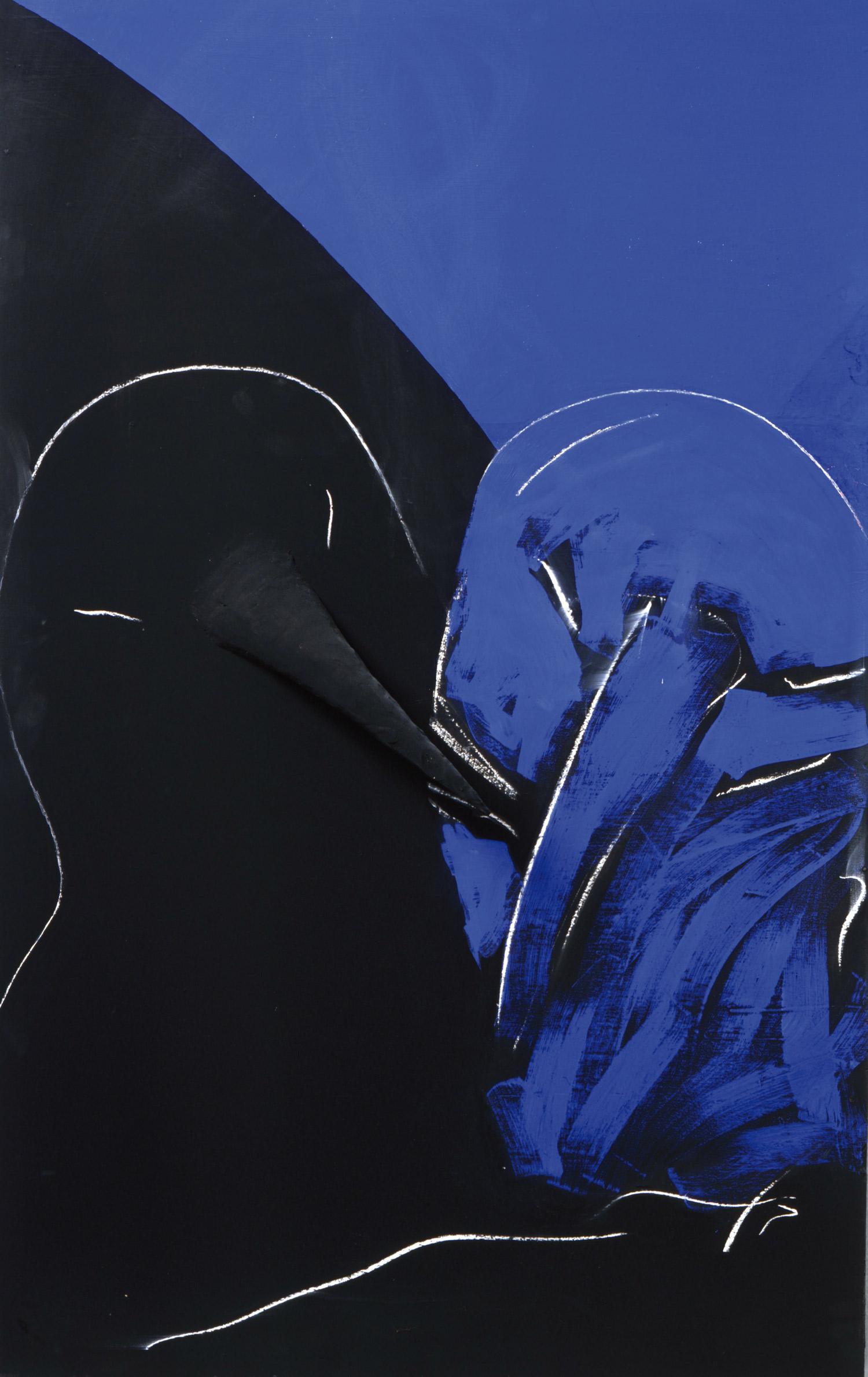

CA: Somewhat flexible, but we naturally had a particular identity to uphold. The Origine group was made up by Burri, Ballocco and Colla. Ours, instead, consisted of Turcato, Consagra, Sanfilippo, Dorazio, Perilli and myself. After two or three years, we all chose our own path. As for myself, after a couple of years I moved on to my “black-and-white” paintings.

HUO: Was it the beginning of the ’50s?

CA: Yes, it was ’54. During that year I made a lot of colored paintings in which the first signs of a transition began to appear, and I also made two or three black-and-white paintings. It was then that I met Michel Tapié.

HUO: What was your position in relation to the Informel style? Was there dialogue between Paris and Rome, or were there strong differences?

CA: There was dialogue, although each one of us chose specific artists for reference. For instance, with Tapié I exhibited my work at the Spazio gallery, here in Rome. He had picked some of my paintings to show together with work by other Italians, such as Burri, Capogrossi, Fontana and Moreni. Later he got me to sign a contract with the Stradler gallery in Paris, which back then showed the work of very young artists. At Stradler I had my first solo exhibition, right after Tapié’s show. We all picked the road most interesting to ourselves. I always looked for reference among the more abstract artists. I liked Hartung a lot, and I would go visit him in his studio.

HUO: What was your relationship to Fontana?

CA: He respected me and I admired him a lot. He came to see me in my studio, and I went to visit him at his. Once he wrote me a letter with some of his thoughts… he has been very important for me. I saw his earlier works at the Biennial, his holes. I also exhibited at the Biennial very early on: a small painting among the work of others from our group.

HUO: I believe one cannot talk about your work without referencing the Informel style… but it’s also true that there is something more structured about your work, since your traits are not like those in the Spontaneous movement.

CA: That’s true, I did not trust the automatic Spontaneous style. But there was a certain degree of automatism when I would get down on the floor to draw, or when I painted in black and white. It’s just that I really enjoyed having control over what I did. The Informel style felt very easy and repetitive, since unfortunately it had become fashionable. By that time I had also met Fautrier and others in Paris, all important encounters for my work. When I made these black-and-white paintings, I used to begin with a drawing. I would make temperas on paper from which, slowly, there would evolve a world of signs, structures, and integrations. The signs had a kind of “return,” in the sense that they would come up again changed, transformed. I would repeat them in reference to past works, but there would always be something new.

HUO: This is translated into drawing…

CA: Yes, there was a translation process. When I had made a painting, I would make a new one using the earlier one as a starting point, but the result was always different…and that was the most important aspect of the new painting.

HUO: And what was the starting point for the black-and-white lines?

CA: I had visited Hartung’s studio, and since then I began with the large lines that crossed each other. Later on, I focused on my own lines, without looking for inspiration elsewhere. It was the fruit of my personal thoughts and fabrications.

HUO: There is also a red line that connects your works, from the earlier ones to those most recent: it’s this scientific aspect that makes one think of cellular structures, micro organisms and biological microstructures.

CA: At the time I was following two approaches: one focused on a scientific biological perspective, with growing and shrinking amoebas. The other approach was more geometric, with work that was sharper, even though there were some curved shapes.

HUO: There is a fluctuation between the more constructive work and that which is more organic. Until when did this process continue?

CA: Until ’60. Then I began to use gray for a couple of years. Following that, I used archived lines: lines placed in rows. I left behind black and white and began using color with a lot of contrast, using the same concept as for black and white. I was always inspired by anti-painting. As a result, I never used fading. I never painted on an easel, but horizontally: on the floor or on a table.

HUO: And what was your relationship to the United States at that time? There was dialogue with Paris, but was there information coming from the U.S.?

CA: Yes, there was dialogue with the U.S., especially after having met Pollock in Rome. I had especially liked the way in which he worked.

HUO: Did you pick up color again after the black-and-white years?

CA: Yes, but a new kind of color, used in a particular way. And after that, I moved on to fluorescent color, which is characteristically very bright. In ’64, thanks to Fontana who had mentioned my name, I had a room at the Biennial.

HUO: Was the curator Lucio Fontana?

CA: That year, Fontana had been asked to be part of the jury. I started working with Luciano Pistoi in Turin. I loved him very much. In Rome the circumstances were not favorable any longer, so I opted for Turin and Paris.

HUO: When did you begin working with plastic? And how did this drastic transition come about?

CA: I began in ’65. The transition took place while working with fluorescent color: through the use of color, I produced light, and so I thought: “Why not produce light with a material?” I found sicofoil, a clear and bright material. Other artists moved on to neon.

HUO: Did you know Luciano Fabro?

CA: Sure. Both him and Paolini were at the Pistoi gallery.

HUO: This is interesting. It means there was an exchange of ideas.

CA: Yes. Carla Lonzi was there as well, a friend of Luciano Fabro.

HUO: In these environments you make, such as Ambiente Arancio (Orange Environment) (1967), the relationship between art and life is incredible. Allan Kaprow wrote a book about the concept of ‘changement,’ of the annulment of the boundaries between art and life. It would be interesting if you could talk about the great ’70s debate concerning the relationship between art and life.

CA: For me, art and life run parallel to each other. On one hand, I made art mythical. On the other, I wanted to understand what lay behind it and I wanted for people not to feel stuck in front of a work. I found that to be too automatic a position. I wanted the audience to be shaken, to love art while discovering that life lies behind it. I understood that life could be combined with art, as had already been done in the past. But first and foremost, I wanted to be a contemporary artist, I wanted to find out what ‘contemporary’ meant.

HUO: Ambiente Arancio (Orange Environment) is a large umbrella with a bed… The scene is reminiscent of a house that serves the purpose of sleeping.

CA: Similar to a house. Yes, I did not like houses as they were at the time. I found them ugly, heavy… I had been an admirer of the Bauhaus, but I saw that people lived in houses that were tacky. As a result, I thought of creating an environment that would exemplify a spiritual and rarefied kind of living…

HUO: You mentioned that Orange Environment resulted from a reaction to unease.

CA: Sure, for me the work meant to push people to live differently, in a more natural way. There wasn’t a philosophical or ideological thought behind it. The work dealt with the idea of an image, of a room. Behind it was the drive to push one towards something unknown that could become a different kind of living. Before anything, it was a fabrication of my imagination.

HUO: So it’s not an applicable model?

CA: As soon as you apply it, everything becomes banal.

Later I made some transparent, cut paintings, where the line disappears. My line has developed over a process: from black and white, to color, to transparency. Even the line has become anonymous. At first it was rich in iconography and extremely varied. Later it became anonymous, and finally it disappeared altogether.

HUO: It’s clear that your work has evolved in a non-linear process. DeLanda talks about a history of a thousand years of non-linear process, and I think this idea is applicable to your work. We spoke about the Informel style… other critics have highlighted the relationship of your work to Pop Art…

CA: Yes, because every time I achieve something definite, I have the desire to challenge myself and others by running away and doing something different.

HUO: Did you want to break with some clichés?

CA: I didn’t want to become rhetorical.

HUO: I believe this is also the reason why there are many young artists who admire your work. It’s because of this reason that there is a dialogue with the younger generation.

CA: Right.

HUO: What has inspired the third great chapter of your work, the new change on the canvas? Could you tell me when and how it happened?

CA: I had moved from black and white, to fluorescent color, to sicofoil. At one point, I told myself: “But there’s no link among these works, it’s crazy!” I needed to make that clear to others. I had gone a long way and I felt the need to make my work more cohesive. As in other circumstances, this pushed me to change, to experiment with new ways. I went to look for rough canvases and I suddenly created large works: diptychs. Each one had an image on it. I was invited by Giovanni Carandente to show them at the Venice Biennial. These large paintings are very different from those in the past; each one contains a particular play.

HUO: Many artists from the ’90s have told me that the feminist aspect in your work has been very important to them. I would like to know more, especially of your relationship with Carla Lonzi.

CA: I had more than a friendship with Carla Lonzi.

HUO: Were you partners?

CA: Together, we revisited women artists from the past. Angelika Kaufmann, Artemisia Gentileschi… I think abstraction was good for me as a woman. Over the centuries, there had been very few women artists and I would not have been able to identify with a specific iconography. The history of iconography focuses on male protagonists: all of men’s adventures over the centuries, their extraordinary achievements, their religious events, their conquests… Eventually I moved away from these feminist standpoints because I realized that I was born a woman by chance, while I was not an artist by chance. At that point I said: “Enough! No more thinking about this!”

HUO: At that time, however, there was a closeness to the world of Nancy Spero and other women who, in the United States, had created spaces in which to exhibit work by women.

CA: We knew all that. In fact, we had put together a little gallery in which we organized a couple of shows. There were some young women we would meet. In the end I left because those conversations would block me.

HUO: In a way, did it become a question of anti-art?

CA: I don’t know. I wanted to find my art, which was my reason to live.

HUO: In the ’90s, most of the interesting artists are women. That’s great.

CA: Yes, because today women artists need to express different needs.

HUO: At the time, was there a dialogue with the positions taken up by French and American feminists?

CA: Yes, we read their books and even went to Paris to meet them. We had groups in Rome, Milan, Turin, and Genova. Eventually, as I mentioned, I moved away from them.

HUO: So there was an active decision to divide your artistic development from politics. How, then, do you understand the political in art?

CA: Personally, I have had some falling outs with politics. I understood that art is far from politics. In the past, I have believed in being politically engaged, but I have since convinced myself that when you start engaging with political specialists, you lose understanding. I believe we all have independent languages, independent ways of expressing ourselves. I don’t like multimedia art, because I truly believe that one must center on one thing in order to dig deep and make of it something profound and significant.

HUO: The use of the phrase “to dig deep” seems like a great way to wrap up. Thank you very much.