Hou Hanru: When I first visited her studio, Cao Fei had just graduated from the art academy. Her parents were officially recognized figures in China and professors at the school. Both were very classical sculptors. Her studio was on the eighth floor, without an elevator, so when I arrived I was exhausted. She showed me a video work that she was doing. It was Imbalance 257 (1999), and it immediately caught all my attention. I fell in love with that incredible work.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: And you connected me to Cao Fei. A few days later I was also totally aware of the work! I wanted to ask Cao to tell us a little bit about these early works she did at the time. They are pre-cosplay, I suppose.

Cao Fei: One of my early works that Hou has just mentioned, Imbalance 257, engages with the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts — my experiences there and with the students around the school. And then, with Hou’s support but also with your support, between 1999 and 2005 was a pivotal moment in my career. Artforum published an article on my early work, including Cosplayers (2004), and that’s basically when both of you started to support my work.

HHR: Actually, with Hans Ulrich we curated the Second Guangzhou Triennial in 2005. And the theme was about how this area around Guangzhou, from inner Guangzhou to Hong Kong — the Pearl River Delta area — was a particular laboratory for Chinese modernization. And, of course, urbanization was the core of that process. At that time we also brought Rem Koolhaas and invited many other people to bring their visions to the transformation of the city, of the region. Cao Fei said she was very much influenced by such interactions between international and local ideas about urbanization. Then we helped her to develop different projects, starting with this very interesting theater piece called the PRD Anti-Heroes (2005) — that was a TV-show-style theater piece.

And I also remember that when I met Cao, the first things I saw, apart from Imbalance 257, were early theater pieces. I was impressed by a performance that she directed and performed. She made it in 1995 — basically she was still a baby — but she had already started to write and direct theater pieces. PRD Anti-Heroes was created in 2005, and she staged this performance with at least sixty people for ninety minutes — actors speaking in Cantonese, of course. And from then on she developed many other works, including the now-classic Whose Utopia? (2006). A lot of this was represented in her research on how the Pearl River Delta transformed, as a special laboratory for China to become what China is today.

HUO: And it’s interesting because, from the beginning, the city played a big role. Cao, your early work has a lot to do with Guangzhou, and with the idea of the extreme mutation of a city, the transformation of the city. And I will always remember when we went there for the first time. You had not been there for six months, and we couldn’t find the house of your parents. I mean, you couldn’t find it because the city had changed so much, so rapidly. This idea of rapid urbanization, mutation, transformation, played a big role. Can you tell us a little bit about the city? Because the city plays a big role also in “Blueprints,” the show at Serpentine we did last year, not only in the VR but also particularly in the older films we showed there.

CF: When I was growing up in Guangzhou, it was just after the Open Door reform. So I got hit with a lot of external culture and interest. Between primary school and middle school, and then of course afterward, during my years at the Academy, for years I observed the extreme changes of urbanization and globalization. On my way to school, be it primary school, middle school, or later the Academy, I would walk past fields. So a very rural area. And then these would develop into these high-rise buildings — a very urbanized environment. Afterward, when I was at the Academy, after many years of observation, I put all my experience into these works. Worth mentioning too is 2003, the Venice Biennale, that dealt with the extreme reorganization of the Pearl River Delta.

Clearly, notions of city and urbanization are a recurrent motif in my work, be it real or virtual or in a parallel world. So, these overlapping temporalities and realities, in RMB City (2008) or La Town (2014), or now, in my newest work, Nova (2019), they will always connect on certain levels again and again.

HUO: It was interesting how in the Guangzhou Triennial we felt we should go beyond event culture, and that an exhibition should produce reality. So we did an exhibition that produced a museum infrastructure, which is still there today. And that, of course, had a lot to do with the conversation with Cao Fei.

HHR: That was, I think, one of the most extraordinary experiences one can have. We were very lucky to be curators of this project. We were working on this project in 2005. And we decided to examine the urban transformation of the city, from theory, discourse, artist actions, and so on. We invited artists, architects — and also it happened that there was an incredible opportunity in that the museum was talking to a developer about building an extension of the museum in the suburb of Guangzhou.

Then we had this ambitious idea to invite Rem Koolhaas to design this museum. And it was not about designing a new fancy iconic museum, but really trying to bring a new concept about what a public institution, a future institution, could be in such a context of urban transformation. Rem visited the site and then made the proposal, which was incredibly innovative and very challenging. It was supposed to be a museum built in the middle of the campus of high-rise residence, in the garden, surrounded by the residential buildings. Rem said he would not do this, because it would be a museum that only served the people who could live in the high-rise buildings, who were, relatively speaking, living under good economic conditions.

But how could we imagine a museum that could serve the whole city — that had an outreach directly to the street, meaning a real public museum? In the meantime, the buildings were already under construction; it was impossible to find an empty site on the street side. So he came up with this incredible idea to insert the museum into the residential building. On several levels of the ground floor, the fourteenth floor, and the nineteenth floor, he decided to insert an institutional structure, to be grafted into the private housing building. So it became a very challenging issue. According to normal urban regulations it would be illegal. And so, from there, we started negotiating with the city administration to allow this incredible confrontation and mixture of public and private spaces to happen. That actually reflected how the rapid urbanization happened in the context of the Pearl River Delta — that “official” planning actually came very often after the constructed facts. It’s something that I called a “post-planning process.”

And that made us rethink what the museum meant to the city, and to the artists. We decided to make this into not only an artistic production machine but also a production machine of public community life in this context. And this museum, now called the Times Museum, continues to function as one of the central platforms for the region’s contemporary creativity. Lately we also opened up a new branch, the Times Art Center Berlin. And that is also an experiment, the first case of a non-European museum actually building an extension in Europe. However, it’s not about having another space; it’s about building another type of platform for cultural and artistic exchange in a new context.

HUO: We felt we should think about different ways of using resources in terms of sustainability. It seems so relevant now, that it started then and it continues today. We made the triennial into a long-duration project over several decades.

I want to ask Cao to tell us about her latest film, Nova, because she wrote Cosplayers soon after we met. At the time, your work already had to do with research, documentation, and fiction. And of course Nova has a fictional theme. It’s a sci-fi film, but it’s directly inspired by individual and collective histories of the district in the North East of Beijing. Can you tell us about the research, and how you then took that and made the fiction shown in Nova?

CF: At the entrance to “Blueprints” (2020) at Serpentine we built up the Huguang setting. There is a photograph of the Huguang Guild Hall [Hongxia Theater], the Opera Theater in Bejing. Around 2008, when I saw the building, I detected a vacuum where I thought I could maybe go inside and occupy the space as a studio for two, three years, and see what I could do with the space. So around 2008 operations stopped at the theater, then I went in around 2015, and now it’s been around five or six years.

While many would look at the space of the theater and probably think, “I need the space to make a movie,” on the contrary, I immersed myself in the history of the theater, and the background stories — the stories of the surroundings — basically to emphasize its history and bring that to the screen.

So, arguably, if you submitted the movie to a film festival, it might lose its meaning, just because the whole movie needs to be contextualized. So that is why it was really important to set up this spatial installation of the Hongxia Theater.

Many people might ask themselves: “Why do computers come up in the movie, or why are there Soviet scientists?” Basically, when I entered the space of the Hongxia Theater in the 798 District, there used to be many factories. Now it’s the art district. Some of the first factories in Beijing — and in the country — produced machines and electronics and computers there. I wanted to capture that history and the background of the Hongxia Theater and its connection to the factories in the movie.

In the movie, set in the wake of the Cold War, there’s a connection between computers and the support of the Soviet Union and the importance of the theater and the screening of movies. I tried to engage all of these elements.

HUO: I wanted to ask something that has to do with time travel — a kind of tele-transportation. I wanted to ask you about the figure of the ghost. What’s the role of the ghost and how is it important? Because the digital ghost that the scientist becomes not only allows the narrative to travel in time but also becomes a kind of specter of history. What’s its role?

CF: The father, the scientist, accidentally turns his son, through the computer, into a ghost, into a specter. When I first entered the Hongxia Theater, I noticed on the walls there were still remnants of old sound systems. So all the white noise and sound and the intangible or invisible layers of the stories, they all would culminate in something like a specter.

* * *

Daniel Birnbaum: If John Cage is right, art is an early warning system, the function of which is to prepare us for the world of tomorrow. Could today’s immersive technologies, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), change and expand the ways we experience art? I think the potential is great, and that these tools will be essential to new forms of international visual culture and exchange. Fei’s VR work The Eternal Wave (2020) premiered as part of a retro-futuristic exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery. Implicit in this sci-fi-like narrative about early computing, time travel, and romance involving a Russian and a Chinese scientist is an entirely new understanding of local and global presence. The gallery itself seemed to be transformed into an experimental terminal connecting heterogeneous spatial and temporal dimensions.

The VR experience starts in a physical replica of a modest Beijing kitchen, but soon you are on a dreamlike voyage in other spheres. On returning, you find yourself back in the kitchen with memories of cinematic and virtual versions of that same space, and of characters that could have been avatars in a multiplayer virtual universe.

Later we added an interactive AR version of the work. With a few modifications the show in Hyde Park could have been connected virtually to parallel exhibitions with audiences in distant places, forming an imaginary maze reminiscent of Jorge Luis Borges’s speculative creations. I wonder if these kinds of works, using VR and AR, will change the structure of the art world?

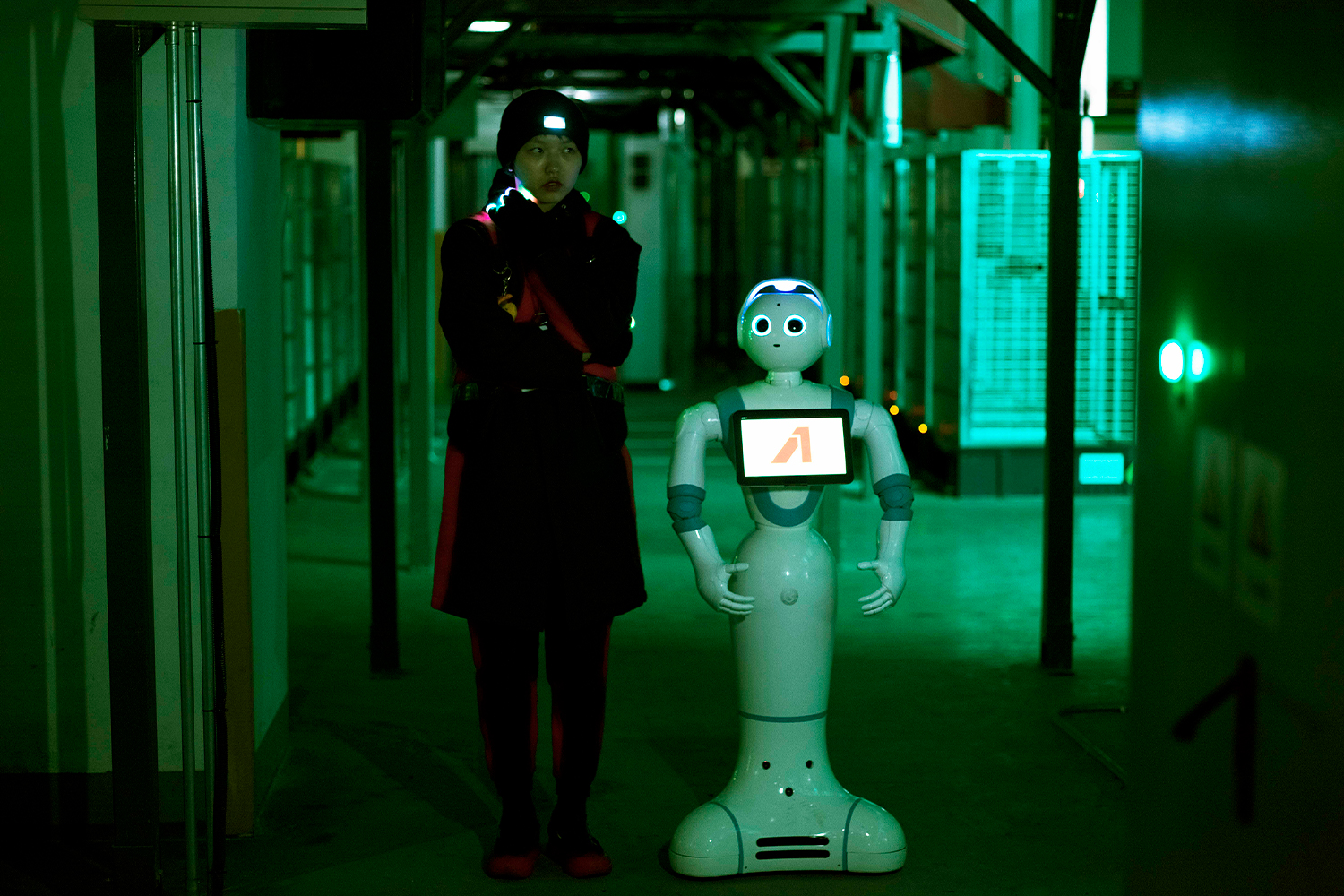

CF: Look at Second Life. Even my son today is playing different online and social media games like Minecraft and Roblox. All the kids and teenagers play that. It’s like a simple version of Second Life, but with a younger generation playing it. But if you look at the tech used by this hardcore online virtual media community, I think it’s not a big leap compared to Second Life. When you invited me to do this project I’m talking about, to do something with virtual reality, that was in 2016. So, perhaps we’re now doing something beyond that, because I feel we’re touching the ceiling of this technology. Because it’s difficult to develop. It’s like, we spend so much time on the platform of virtual social media, but we still feel we are alone. We still think something is strongly lost, the whole generation. Also, I can’t imagine my kids’ generation. All kids want to be YouTubers. They don’t want to do any job. They don’t think “artist” is a future, because not too many fans follow artists on Instagram. But there are millions and millions of fans following YouTubers, and also they can make money. So, going back to our topic, I think emotion is very important for the VR. Because I’ve seen so many VR pieces. Some are very “tech,” right? Some are very entertaining, like “Wow!” Right? I don’t feel emotion in doing that, and that is very important. Also because the headset is very heavy, and the people helping you in the museum, the assistant or the guide: “Look here. Touch the table. Be careful, there’s a step.” All these things distract you from the experience of VR. And also the content is physical. So, I think we make it in our piece. I think we give the sense to people, and also people can feel the emotion.

HUO: There’s a strong moment of empathy in it. And that is a good transition: I mentioned this is a conversation in three parts, and we’re now delighted to welcome Philip Tinari. Phil, similar to Daniel, you and I have worked for almost twenty years on many different things, often related to Cao Fei. And now we’re going to talk about the future, about an exhibition you realized with Cao Fei, which is her first very big exhibition in Beijing, “Staging the Era.”

And of course, Phil, you and I did this book together with Karen Marta, about the future, a few years ago, with Cao Fei. We actually participated in and outlined her ideas for the future.

Philip Tinari: Thank you. It’s really exciting for us to be looking ahead at the show. I mean, it’s kind of amazing when you think about the Chinese art system and the international art system — that you can have an artist like Cao Fei who has shown in major institutions all over the world, in New York, London, and Paris, and so many other places, but, for whatever reason, there has not been a major show in China.

We’ve had this idea to make a show together already for five years now. Going back to 2015, 2016, we began talking. A lot of things happened with UCCA, a lot of things happened with Cao Fei, and now a lot of things happened with this virus. So the show should already be opening September 2020, but, like everything, there’s been a delay.

We have this tradition in UCCA of doing really substantial presentations of who we believe are the key figures of Chinese art — also alongside an international program and more thematic kinds of shows — and this fits very squarely in this tradition of major exhibitions we’ve done with figures like Xu Bing and Qiu Zhijie and others over the years. One of the most interesting things is that Hongxia itself is a part of the neighborhood. So, thinking about the context, to be able to show some of the work we were just talking about in the actual place where it originates or is evocative of is quite different but quite exciting. So, Cao, how do you think about presenting your work on a large scale to a Chinese audience in Beijing, but then also presenting work that’s so much about this very part of Beijing and this particular history, which also includes the buildings of UCCA and 798 and the whole Hongxia area, as well as your studio.

CF: I think having a show in China is so important for me, although it’s not easy because, like Philip Tinari says, this is so difficult. Other museums are asking me to do shows here and there, but I always say I want to keep the show at UCCA — my first traditional, local show in Beijing. For me, in China, UCCA is the most academic museum — I had an academic team to go through these works, and a publication. It’s important for the local audience to look at this project and think about this project. Thinking about the show at Serpentine, it’s hard for the audience to see the real Hongxia Theater. But in Beijing, after the show, they can hopefully visit the theater and look at the real kitchen. That also is a special experience, not only through the VR piece. For sure we have to have this VR piece; that is totally different. It’s more dimensions. Because in London you have the VR experience and the film experience, but in Beijing you will have the real experience. That is gorgeous, right? To show my work in front of my home.

If you look at my Instagram, I can look at my friends, my “followers.” Most of my followers, sixty percent, are from New York. Then London, and then I would say the rest is Shanghai, then Beijing. Beijing is only like five percent or less of my Instagram. So you can see, most of my fans are not based in China. So that means the UCCA show also would be important for students. They may know my name and some of my works, and some information from the internet, but they never see, totally, the whole body of my work. That is also very important for the local audience.

PT: I think it’s so interesting too, because when you have these major exhibitions abroad, a lot of effort needs to be put into just explaining the context. You have to talk about economic reform in China, and talk about the difference between Canton and Beijing. You should talk about youth culture and manufacturing and all these different things. But here, I’m super excited just for the chance to be able to create a different kind of encounter that in a way doesn’t have to do the work of conveying that information and establishing that context, which I think in a way frees us to approach the work more from a poetic or aesthetic level. And also, I’m excited for the resonance that people will feel with the work, because so many of these stories are also their stories. These are stories of a generation and of a country in transition. So it’s kind of incredible that this body of work has been missing from the people for whom it’s probably the most relevant. I mean, it’s compelling internationally, obviously, but I just think there’s going to be a whole new generation of people who will come to a whole different idea and understanding of art through the show. I’m so excited to have worked on it with you.

CF: The space at UCCA is so big. I think it’s the biggest space out of all my solo shows. So it has been challenging. The ceiling is very high. I remember when, in 2008, Philip saw my iMirror (2007) work in New York and he cried. Because iMirror is filmed in Second Life, right? It was like a pre-virtual-reality community. So that’s what I want to keep doing with the VR piece. My goal is to make emotion. Because the tech, the social media, is very cold. So I think it’s how we can find the emotion, the human being, in this platform. That is the major reason why I’m interested in technology — even RMB City is about the connection, about doing the activity. It’s not just about technology, or about a fascination with the future.

PT: I mean, in Second Life your avatar was called China Tracy, right? Of course, she was a projection of you and it was a different kind of virtual world, but I think there’s a way in which your story — I mean, you are a kind of an avatar for this whole generation, born alongside opening and reform, for this really incredible range of historical and technological and ideological moments, crammed into the space of just forty-plus years. So, it’s exciting to put that all out in front of a larger public and see how they react.

HUO: Now I wanted to ask Cao Fei to tell us about Do It, because during the past year of lockdown something very interesting has happened. Paul Chan always says that connecting is great, but it’s actually de-linking that is sublime. And, during a moment when so many people have spent so much of their time in front of screens, it seemed important to also think about projects that we can do off screen. So we started a new Do It with the Serpentine — also with Independent Curators International and Kaldor Public Art Projects in Australia and Google Arts & Culture — and Cao, you have been part of Do It from the very beginning, and you did a wonderful Do It idea about finding eyes in your apartment. Can you talk about it?

CF: Yeah, it’s actually in a very old Do It book — the English version and then the Chinese version. I think it’s a special time for us to review or redo it. In lockdown time we’re focused very closely in the home. Everything is like zoomed out in your space. So one day I wake up and I look at my floor, and I can see a lot of eyes in the wood pattern. It’s really like an eye with a tear. And then I tried to take photos of all these eyes in the wood. And then I posted a Do It on Instagram. It’s like counting how many eyes are in the home.

In lockdown time we have much more time to look out of the window and look outside at at the street at midnight. It’s like everything is extended. So I think it’s good timing for a new Do It in this isolation period.

HUO: And then I wanted to ask you about TikTok, because one of the things I started during the lockdown is I joined TikTok. It actually has to do with this book by Vincent Despret, What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions? Bruno Latour says it’s an amazing book because you’re about to enter a new era of scientific fables, by which I don’t mean science fiction or stories about science but, on the contrary, true ways of understanding how difficult it is to figure out what animals are up to. On TikTok I started to interview animals, on my daily walk in the park, about their unrealized projects, and that has become my TikTok account. It’s interesting because it’s actually the beginning of artists joining TikTok. It’s a bit like many years ago, when all of a sudden on Instagram many artists started to join. Are you using TikTok? What do you think of it?

CF: Oh, I don’t have that. But I’m watching your TikTok on Instagram.