Confronted by Bruce Nauman’s work, the viewer becomes psychologically disturbed.The artist’s efforts to turn an idea into an artwork, to persist in the process and to render undesirable the word “finished,” puts whoever looks at it and whoever writes about his artistic research in a spin; everything that is clear and visible is at the same time hard to see and to understand. Each attempt to define his artistic practice is in fact weakened to the marrow by the nonchalance with which the American artist (Fort Wayne, Indiana, 1941) shifts from one technique to another.

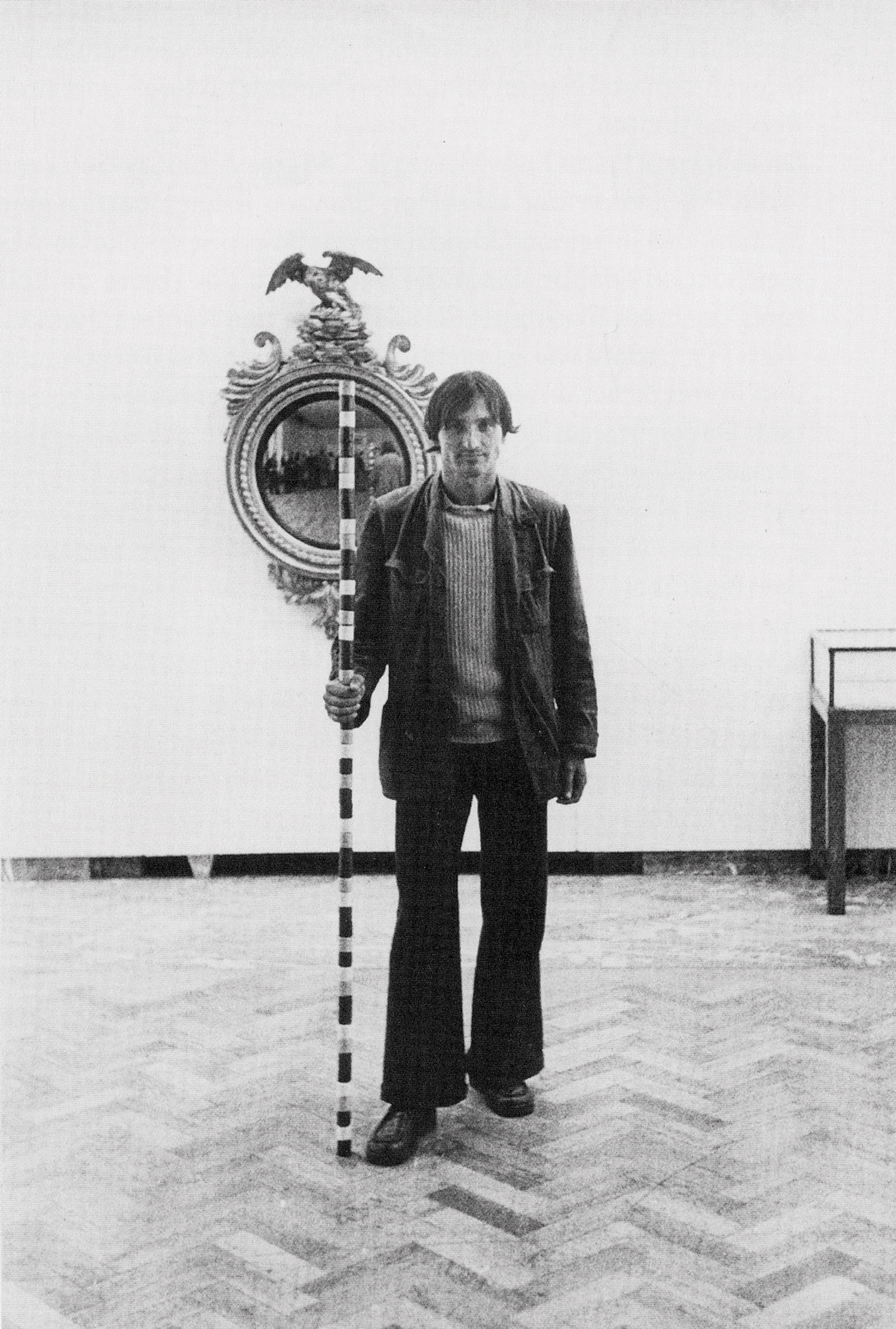

From acoustic corridors to performances; from neon to fiberglass and synthetic resin sculptures; from dance pieces to films; from drawings to cast body parts; from simple gestures to flower arrangements, through to language, both written and spoken, Nauman has always addressed the investigation to himself and the human being. Nauman’s speculative research is aimed at comprehension of how we exist in the world.

Moreover, Nauman’s phenomenological interest in space is obviously one of the privileged passkeys to his work, in which the difference between seeing through the eyes and experiencing through the body is reduced to zero. This is one of the reasons why each definition, historical reference and critical assessment of Nauman’s work often seems quite inadequate. The uneasiness that emerges through our incapacity to find the appropriate words grows in parallel with our awareness of the centrality of language in his work, which — as in the case of the light, sound, photography and performance pieces — creates a sense that exceeds the production of the object.

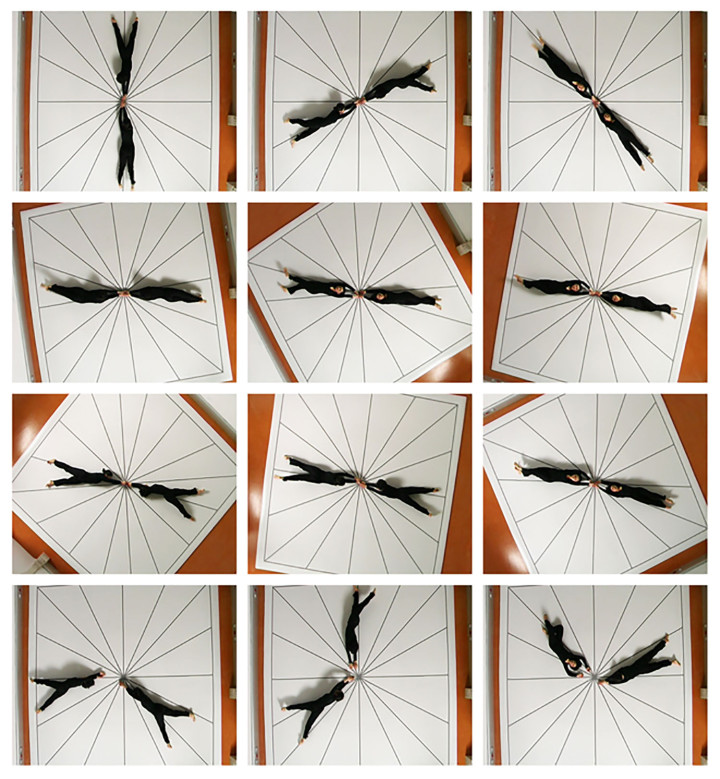

On the occasion of “Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens,” curated by Carlos Basualdo and Michael R. Taylor and organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which marks the artist’s participation in the U.S. Pavilion for the 53rd Venice Biennale, two of the exhibited works are The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths (window or wall sign), 1967, one of the first neons realized by the artist, which recently joined the Philadelphia Museum’s collection, and Untitled, 1970-2009. If, in the first case, Nauman drew with neon a spiral containing the famous statement, in the case of Untitled — an unrealized work from the “Poems” series with Nauman’s instructions to others on how to repeat the gesture — it’s still the artist that puts into writing the screenplay aimed at meticulously leading the movements of people, who roll themselves clockwise on a carpet, thus drawing a spiral. The act describes the space, while a fixed video camera films the movement.

These seminal works by Nauman, which exemplify the double nature of the exhibition project — between the presentation of historical pieces and the production and re-activation of new sound installations — also reconfirm the artist’s attitude toward creating open cognitive situations, often linked to spiral shaped figures that aim to emphasize the psychological differences between the body exposed or hidden in public or private spaces.

One of Nauman’s main topics in the exhibition is precisely the polarity between public and private, presented through an extensive thematic selection of works — the re-activation of Untitled and a new sound installation, both produced in Venice in collaboration with the students and the teaching staff of the University of Ca’ Foscari and Iuav. “For me the choice of Untitled comes from it being an element of connection,” Basualdo explains, “between the performance period, where the studio space is mapped in the performance through the body, and the following series of tape works, where the action exists without the body. Untitled informs us of the link between before and after.”

Therefore, the exhibition seems to be characterized by the plus sign: more works, more actors, more curators, more exhibition spaces, maybe more visitors, surely more questions raised.

Besides the traditional venue of the U.S. Pavilion at the Giardini, the show extends across the city and takes up the great hall of the ex-convent of Tolentini, now head office of Iuav, and the exhibition spaces of the late Gothic palace of Ca’ Foscari, which overlooks the Grand Canal. “The idea to involve the two locations of the University,” continues Basualdo, “arises from the topic of public and private, and from the search for an ideal space. Tolentini and Ca’ Foscari are two examples of places where history has stratified in different ways. A palace first, and a former convent second, marked by the work of Carlo Scarpa, which Nauman really liked. The relation between public and private is also further emphasized by the fact that the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation is the owner of the U.S. Pavilion. The difficulty of grouping together these venues constitutes part of the show, because it operates also on an institutional level as it creates relations among the city.” If it’s still true that “the important thing is the tension of how to deal with the situation,” — as Nauman stated in an interview with Michele De Angelus in 1980 — there is no doubt that on this occasion Venice is obliged to produce that tension. The relation between the exhibition and the city — seen as a social structure, a stratification of forms and acts, an alternation between empty and full, or a constant confusion between public and private, inner and outer, exposed and hidden — is in fact very close. The curatorial will to unhinge the function and the meaning of the U.S. Pavilion itself — which explodes from the Giardini to fall on the crucial points of the city — as well as Nauman’s visceral interest in examining the psychological capacity of different spaces reaches a climax here. Furthermore, especially in Venice, speaking of space alteration, repeated sounds and echoes, straight and twisted, cube or sphere, reflects a sort of consonance, or at least relation, between the topological predisposition of Nauman’s work and the city itself, the space of which is, as Basualdo puts it, also a “symbolic space, to be experienced every time it’s being crossed.”

Just like Nauman’s first works from the second half of the ’60s, pointed at making the viewer both an actor and an observer of the action (conscious of an experience that hasn’t to do just with the idea of the space, rather with its sensation), the exhibition proposes itself as an experience and aims to question itself as if it were a work of neon, fiberglass, film, language, action or photography.

Nauman’s interest lies in the human being as a body, able to understand the logics of the space that surrounds him, turning the subject into objectivity. “A topological reasoning is in line with the character of the city,” states Basualdo. “The topological vocation of the exhibition project is meant also to unhinge the heavy colonial-fascist charge inherent to the idea of a national pavilion. The pavilions have in fact this double origin, which overlaps in the case of Italy. However, with regard to the U.S. Pavilion, we deal with the U.S., a non-homogeneous area, a union of different cultural contexts within a territory. Also this could be a topological relation. In this way, the exhibition also becomes the space that links one site with another.”

One could read this consonance also in the relationship between the curatorial vision and the artistic research; if one considers that in Nauman’s art there’s no distinction between the nucleus and the surface of the work, so too the exhibition appears as a continuous experience of the Venetian urban topology. In this sense, for the first time the Pavilion functions not so much as an exhibition project that escapes the limits of the Giardini, but rather as a discourse about the city, also mirroring its logic in which the artist’s research is reflected and expanded.

Is it utopian thinking to understand the exhibition as a parallel development of levels, where the character of the context entwines with the artist’s modus operandi? What kind of risks does this shift of the studio practice into the perimeters of a city so densely stratified as Venice imply? The confusion grows along with the discomfort.

The continuity of Nauman’s research, which structurally has neither a beginning nor an end, leaves whoever looks at and experiences his practice in a state of suspension, waiting and never-ending tension. It is not by chance that Marcia Tucker, in her autobiography, with regard to Nauman’s works exhibited in 1968 in New York on the occasion of his first solo-show at Leo Castelli, remembers her first reaction, “This is junk!,” while also recalling Leo Steinberg’s statement: “If an artwork upsets you, it’s probably a good work. Otherwise, if you detest it, it means that it’s excellent.”