Hans Ulrich Obrist: Your last collection is born of a dialogue with the artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Grace Wales Bonner: Our conversations were important. I was thinking about the street and about an idea of a character, a street preacher. That was something I was talking to Lynette about, how someone on the street can transform their environment through speech. I was reading Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison and thinking about the transition in the end where the main character realizes the power his words have over the community. So that was a starting point for me, thinking about how you can transform a community through sound, how you can somehow transcend your environment. But I was also connecting that to renaissance portraiture, formations and expressions on the street through time.

HUO: So renaissance street representation?

GWB: Exactly. I was looking at renaissance portraiture, also reading about the Friar Savonarola and his band of “blessed innocents” — children dressed in white robes, who would walk the streets of Florence singing hymns and collecting vanities. The “spiritual” characters in the show came from those scenes.

HUO: The outfits are all the individual portraits.

GWB: In a sense. For me, there were four characters that I was thinking about: spiritual/street preachers, renaissance effeminate sons, Jamaican rockers, and 90s intellectuals — they all express a kind of individualism.

HUO: You always work with different practitioners.

GWB: It’s very important for me to use my platform to interact with people that inspire me and can allow me to see the work from a new perspective. I felt like this time I found an amazing group of collaborators. I’ve always been really inspired by Yiadom-Boakye’s painting, the complexities of the characters and the gentleness that she represents them with. I was really nervous to ask her, but I showed her my research and explained what I was doing. When I met with her we talked about James Baldwin and his relationship with his father, that was what she had in her mind when I told her about this street character. Lynette wrote a poem about a preacher, and that took the collection quite a lot further in terms of building out the narrative.

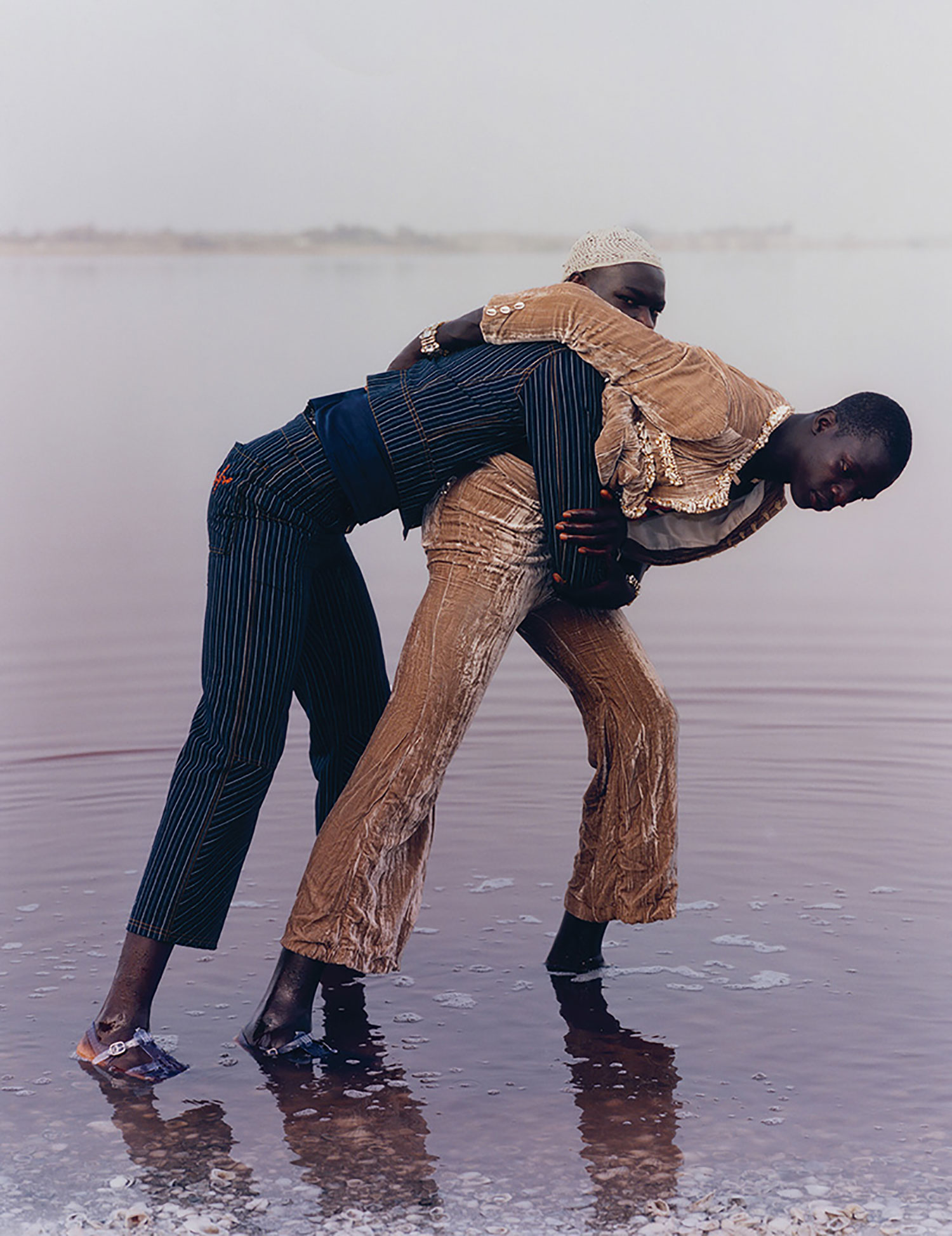

I also collaborated with Sampha and Elysia Crampton, who both worked on the music for the show, which further developed the breadth of the idea. I imported a sound system from Notting Hill Carnival. Again it was the idea of a street sermon, the way sound in a public space transforms how people engage with the street. I was always thinking about this idea of elevating the street, making the characters more heroic and cinematic.

HUO: The models all hold their hands on their hearts. Is that part of the choreography?

GWB: Yes, I worked with Michael John Harper, a friend and muse, on the choreography. I feel, as shows can be very formulaic, playing with simple gestures can be very impactful. Elysia’s music started quite romantically, so the contrast of this opera and the aggressive speed at which the models entered the room, was kind of confusing for people at first, until the intensity of the music kicked in. With the choreography, Michael John explored the familiarity and distance of seeing people on the street. The pacing was very important. The “spiritual” characters in white would walk slower than the others and have more of a grounded presence in the show, they were the anchors.

HUO: Tino Sehgal said we need intensity for gathering the people.

GWB: I guess just having these different inputs in the collection gave me the energy and the strength to be so ambitious and bold with it, because my approach is very gentle. I felt what I was saying felt very true and meaningful to me at the time and I needed to be very strong with how I communicated it. There was an immediacy to the clothes and the choreography, a sense of realness I felt I could convey. Having spent the whole of August in Tambaocounda, Senegal (a residency at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation’s Thread Cultural Center), I also got a feel for these expressions in Tambacounda too, so I want it to be quite global, referencing street style in Paris, Dakar, Kingston from different time frames.

HUO: How would you summarize that message?

GWB: I think it’s about freedom, that’s the most important thing.

HUO: It’s the title of a song by George Michael. But it’s also a very relevant topic right now, politically. Do you think about your work as political?

GWB: I think it’s a reflection or a reaction to the times. I was thinking about the immigrants in London and about how I got here and my Jamaican grandparents coming as first-generation immigrants. So there were some of those characters in the show, people coming to a different place, changing the way they dress or trying to follow some conventions by the way they dress. I guess the attempts to show lots of different characters was part of a kind of celebration of multiculturalism.

HUO: Etel Adnan said, “The world needs togetherness, not separation. Love, not suspicion. A common future, not isolation.” Seems to fit, no?

GWB: Yes, that’s it. So in that way this collection is important for me, because it was just about celebrating the beauty that stems from cultural collisions.

HUO: In a previous interview you told me that Thelonious Monk inspires you for music. So I want to ask you about Thelonious Monk and also about these two new musicians — Elysia Crampton and Sampha — you’ve collaborated with. What inspires you about all of them?

GWB: I guess the reason I like Thelonious Monk is because he does something very complex out of quite idiosyncratic gestures. I love the idea of that and how you have to understand tradition in order to dismantle it or make your own space within it. As for Sampha, I’ve been collaborating with him for the last year on a project. He’s an incredible, instinctive musician, very soulful. His music is very powerful and allows you to connect with emotion immediately. Elysia was very different from him and she is more challenging to my aesthetics, she pushed things so much further. Her soundscape felt like an industrial collage and the show needed that energy. When I was talking to Elysia about music I was sending her recordings of Fred Moten reading some of his poems, and some of Amiri Baraka — I am very interested in ebonics. It was special that I could send literature to Elysia as a starting point.

HUO: And then, to talk about the future, do you have unrealized collaborations that you dream to make?

GWB: Definitely. I mean, I’d love to meet Fred Moten. I think we are planning to meet quite soon. Also, I think about writers like Ben Okri.

HUO: Have you met Isaac Julien yet? Has that happened?

GWB: I have met him, yes, we were both part of Duro Olowu’s show at Camden Arts Centre, “Making & Unmaking”, last year. He’s probably my biggest film inspiration. I have recently been obsessing over his films again.

HUO: So I wanted to ask you to tell us a little about your collages. How do they work? You basically find stuff in magazines and newspapers. What is your relation with the analog? The twentieth century was the collage century in terms of analog collage, and now we’re sort of living in a digital collage age.

GWB: The way I work is still pretty analog, just using images from books or found materials. And I usually use a photocopier, so I don’t do anything on the computer really. For the last things I was working on in Senegal, I was layering different papers and cards over these images of landscapes and trying to create these windows into spaces with quite a minimal approach. But I was also working with people at the residence, and children, just to rearrange the materials, so it was done through chance. I found a lot of imagery in markets. It’s more a collecting practice.

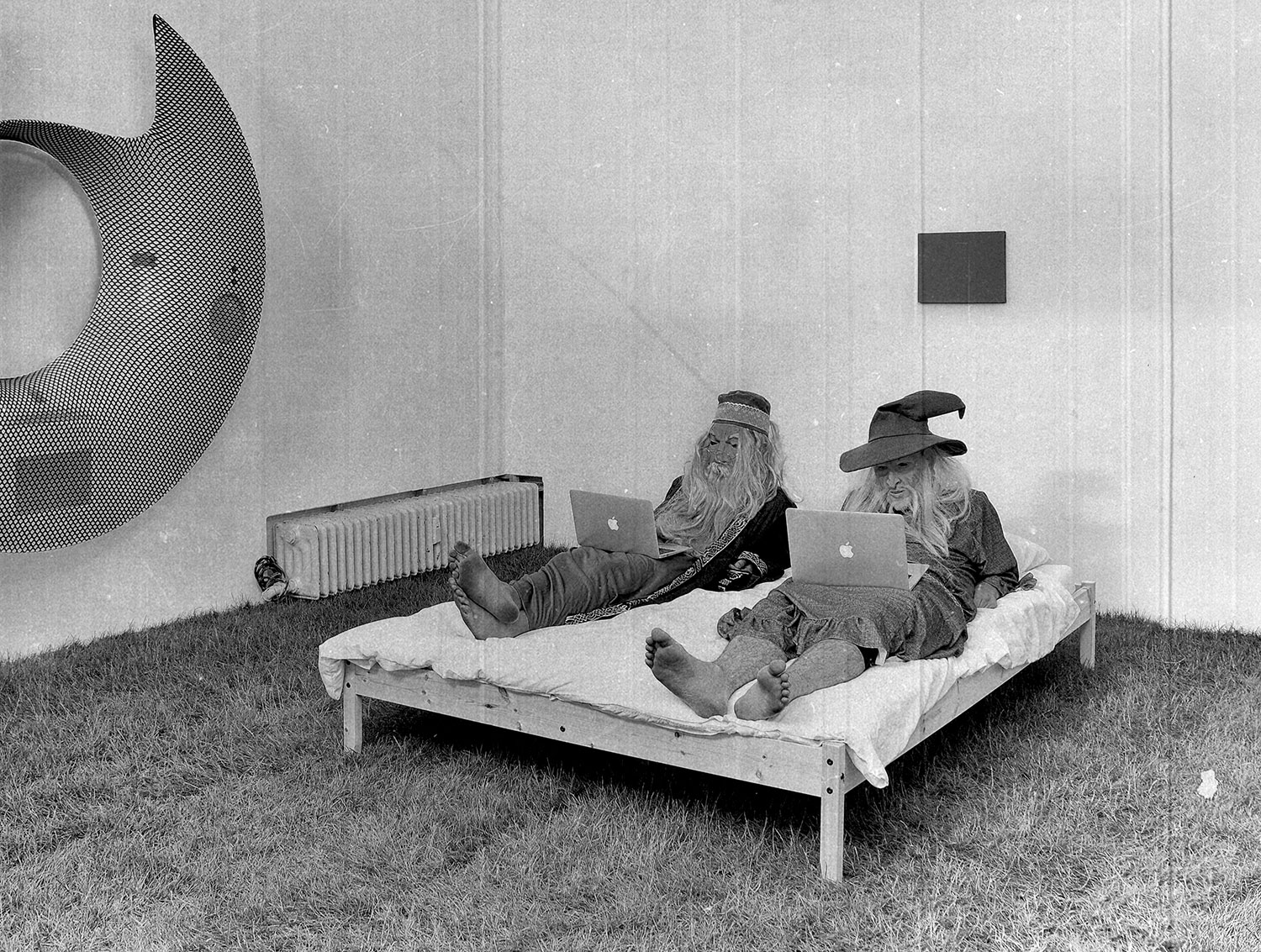

HUO: And then of course there are your performances. Because I think your fashion shows are performances in their own right. You did this amazing performance at the Serpentine Marathon, “Everything’s for Real,” in 2015. You collaborated with Moussa and Moussa, two musicians.

GWB: They are actually cousins from Burkina Faso. When we got them together they hadn’t seen each other for like eight years, so it was quite special to work with them. I guess I kind of directed them — even though I’m not a musician — to do something in a certain way.

HUO: Did you do any other such performances “outside the box”? Which did not happen in the fashion world?

GWB: So, after my first show I got invited to the Victoria and Albert Museum to do a presentation in the Raphael Gallery. I set up this tableau and had a choir singing black spirituals.

HUO: Can you talk about your previous shows and the main ideas behind them?

GWB: My last collection was called “Ezekiel.” I was thinking about the idea of a return of a black savior, thinking about Haile Selassie and what he meant for the Caribbean, through Rastafarianism. So that was a way for me to connect Africa and the Caribbean. The collection was quite ceremonial but also quite severe, there was a strong religious undertone. I was quite restrained with the kind of tailoring I worked on, it was very structured.

Among the previous ones, one was inspired by Malik Ambar, an Ethiopian who moved to Western India in the sixteenth century and then became an important military ruler. It was about this transition and cultural translation between those spaces, looking at threads of similarity, black dress and Indian dress, Bollywood and Nollywood, and the sounds that spiral from there. I was reading about the African diaspora across the Indian Ocean and Africans in India. I also did go to India and did visit Siddhi communities, and kind of tried to revisit that journey almost. Another collection I did was called “Spirituals I”, which resolved some of the ideas that came from the trip, reconsidering history through Afrofuturist thought and Sun Ra.

HUO: I’m always thinking that your practice is so generalist. It’s so — in a renaissance way — all-encompassing: music, literature, art, architecture. Your fashion shows made me think about Diaghilev. You bring in a composer, you bring in a visual artist, you bring in a poet. In an interview for matchesfashion.com, you said that you do research collecting cloth, listening to music; the picture gets wider and wider and you really get into an idea. Is there any unrealized research? Is there any research at the moment you are doing?

GWB: I guess, I’m just collecting things, or connecting strands together. While I was in Senegal I was collecting all of the Facebook profile art. That is something I have just been storing. That’s digital. And then I guess I have random collections of things which I’d like to show one day, physical and digital. I would like to be doing more collages, but I don’t get the time to do everything, so I’m trying to do residencies where I can actually spend time in between shows working on more art projects.

HUO: It’s interesting to think about the connection to craft. I spoke years ago to Helmut Lang, when I was a student in the 1980s. He said he was never going to have shops of his own, that he was going to infiltrate distribution structures and sort of emulate and change them. I was wondering how you see the evolution of your own brand.

GWB: I think I do like the idea of infiltration, in the way of just existing in a space that is in the same kind of environment as an established luxury brand. I think, for me, as a mixed-race designer, this is important. What I’m trying to do is elevate a certain cultural perspective into the same world, to be respected in the same way. So that’s what drives me, an ambition to be on a similar playing field in terms of stores and positioning. I feel like people can engage with what I’m doing at different levels, whether that’s through publications like Everything’s for Real, through visuals, or through the clothes. Although there is something escapist about some of the images I present, I feel the clothes I make are quite real, in a way, and maybe this season was even more real. So I think the clothes are commercial.

HUO: But there is the politics in it. I was wondering what ties it all together, with all these shows that are so different. You said that black representation is something you want to discuss solely — it seems to be always there. You say you are personally and emotionally connected to it. And this brings us also to your favourite painter, Kerry James Marshall.

GWB: I guess for me it’s not a seasonal concept. It’s something that I’m deeply interested in and have a personal connection to — so that’s the thread. I think it’s a reaction against how black culture might have been used in fashion. So for me, this is the study that I want to commit to. I think about Kerry James Marshall, who is a huge inspiration — the way that he is so consistent in the representation and the strength of his characters and his compositions that renegotiate histories. His images are seductive and beautiful. I also think about the unmistakable scale of the paintings; they command space and attention and this has an important impact for young people in institutions. I’ve heard him talk about this intention to keep producing images of blackness, so that you’re broadening the spectrum and you’re kind of flooding people with that kind of imagery until it becomes normal. I think that’s probably why I’m on this path as well. That is what I am trying to do with it.