Bri Williams’s work drifts between feeling and intellect, eroding the distinction between the two into an embodied knowing and experience of a world governed by belief systems that are now bringing about its demise. Antique furniture fragments, obscure objects of spiritual or personal significance, and preserved detritus unfurl and meld within tactile encasements, forming installations and assemblages that open onto the artist’s inner world. Borrowing from Christian iconography, Americana, and other mythologies underlying collective consciousness, the resulting psychic space of her work is embedded with intimate memories and familial connections alongside wider, repeating histories of oppression and violence. As Williams’s vocabulary defamiliarizes her abstract symbols in gelatinous shards of resin and soap molds, scratched and scraped surfaces, burned wood, and occasionally taxidermy, she undresses the pretense of certainty in narratives of the United States — religious and political — that cloak insidious hierarchies based on ideas of bodily and spiritual purity.

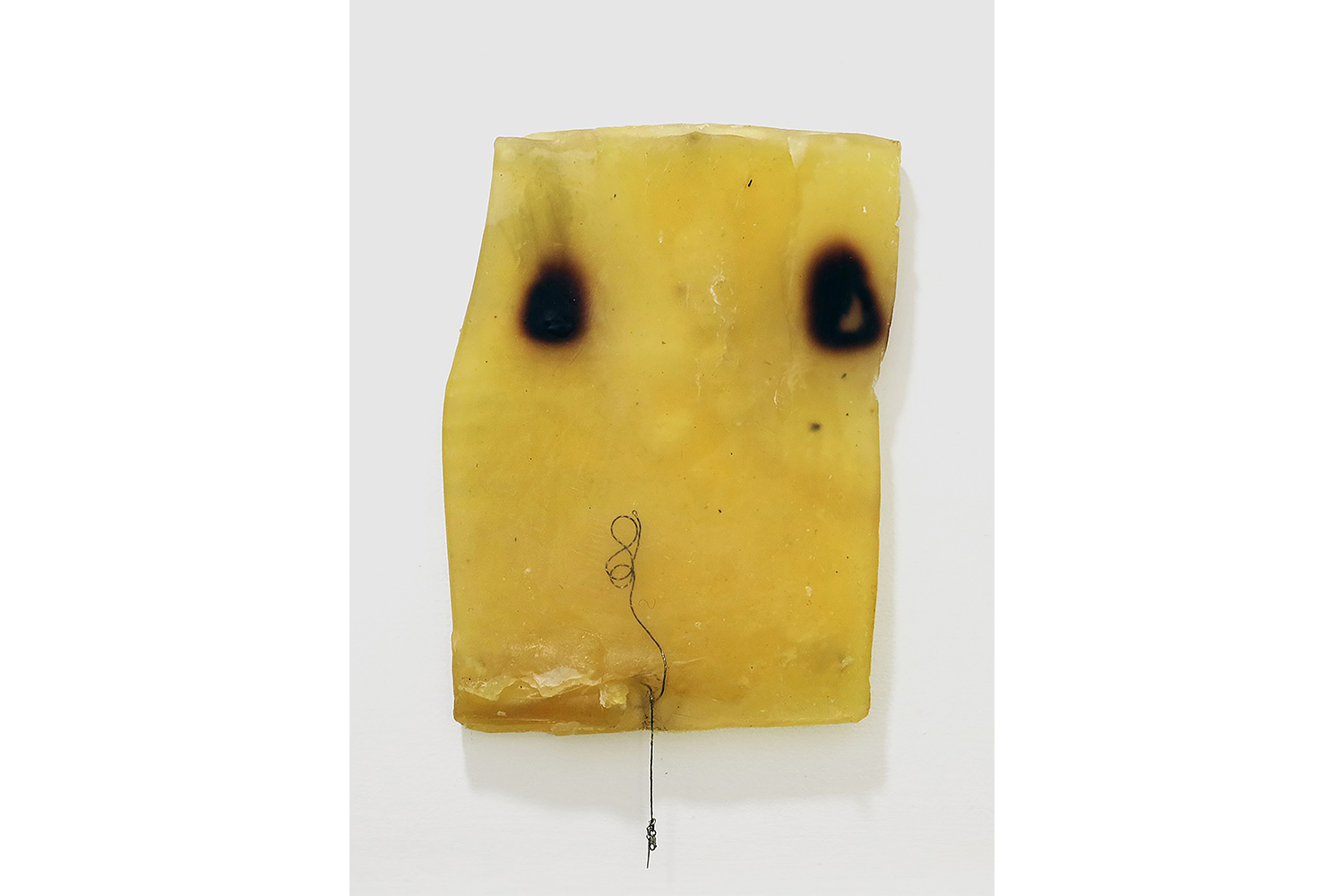

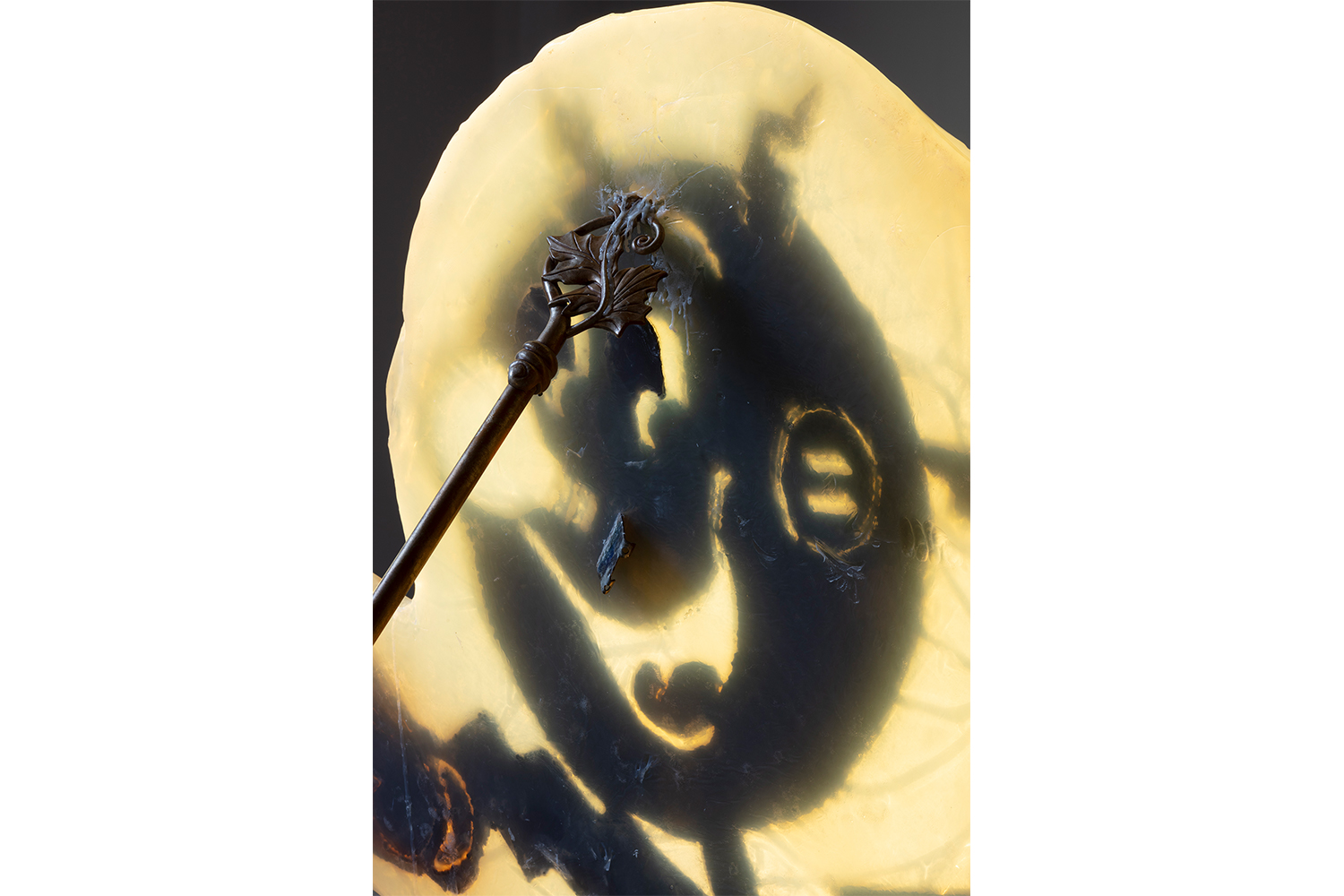

Often experimenting with organic or otherwise malleable materials — and with them, connotations of flesh, cleanliness, death, and mutability — the artist engages a kind of alchemy. The work of Eva Hesse, also known for its use of natural materials and tortured forms, comes to mind, as Williams’s surfaces — burned or worked to ooze and scar, sweat, and leak, to consume themselves — push and pull between the act of employing control and selectively releasing it, allowing these microcosmic systems to destabilize and assume a life of their own. Through these material transformations and their resulting abstract poetry, Williams’s work gains a distinct pathos: one of questioning, of standing on the unstable ground that accompanies the fear, or pain, of processing our contemporary landscape. But Williams’s found and made reliquaries, seemingly of antiquity, and period-like rooms do not seek to pictorially represent this landscape, to replicate and repeat it, and thereby perpetuate its image and violent impact. Instead, her work viscerally conjures the space of a mind bearing witness to the present state of disaster, a realm filled by very real and active demons.

Mirroring her ongoing inquiry into paradoxical power structures that ideologically, physically, and psychologically violate human safety, Williams’s works produce a structural tension and affect that suggest a sense of dissonance — “the unease a person feels when they have two or more contradictory or incompatible beliefs,” as she explains. Her recent exhibition, “Out” at Progetto in Lecce (2021–22), in fact included a work titled Dissonance (2021), the first painting Williams has shown. Marked by a heavy impasto, with a red and earthy brown surface made with letter sealing wax, the painting’s central figure is a long, narrow bundle of thorned twigs resembling deteriorating human bones or a severed spine. Carrying the slightly sweet smell of the decaying raspberry bush from which the twigs were cut, the work obliquely refers to female saints who are posthumously celebrated with undying love for iconoclastic beliefs met with torture and death. “To be feminine, then, is to die,” Kate Millett wrote in The Basement (1979), her meditation on a domestic murder. In Williams’s first solo exhibition, “Lying is the most fun” (2018) at Interface Gallery in Oakland, the artist fashioned a headless horse, titled Medusa (2018), to reframe the mythical character’s curse as a source of agency, allowing her to freeze intruders in their steps, to ensure herself a safe space, and to effectively reverse the direction of the gaze. Throughout the elegiac theater of “Out,” Williams likewise generates a dialectic between the means of survival and death — both literal and loss of power — along with the emotion of trying to release pain and ailments from the body.

In “Out” at Progetto, Williams finds in the oppression of female saints, witches, and the history of the pagan dance ritual La Taranta (The Spider) a form of exorcism, or an escape from the bondage of abusive power, continually pointing back to the body and its possibilities for healing and regeneration. As Williams writes of La Taranta, “In connection with the brutality of the torture of the witches, or of women in general, dancing became the accepted release of this shared inner subjugation.” Williams represents the dance not through its depiction, or through images of the brutalized saints she specifically references — Saint Agatha, accused of blasphemy by refusing the advances of a religious leader, and Saint Apollonia, who was threatened to be burned alive and instead plunged herself into the flames — but through indications of the presence of immense suffering and a kind of self-possessed force of female resistance. In the exhibition’s poetic form of address, Williams figures the body just beyond legibility, presenting its absence as a death but also an escape, and abstracting it as a remnant or artifact of pain left behind: a torture tool for removing teeth (Saint Apollonia, 2021); a robin’s carcass (Seven, 2021); or the fragments of raspberry bush branches with sharp thorns acting as a threat and a defense mechanism throughout several works on view, including Ingrown (2021). Questioning the conditions of Christian martyrdom while considering death as a kind of rebirth, the work resembles a burial plot and mound of land for planting, earth piled on the gallery floor, framing a glowing surface of soap and resin. What world might grow in place of the death and destruction of prevailing belief systems?

Williams grew up in an Episcopalian church, where her great- grandfather was a bishop. On one hand, the artist and her work are influenced by a deep reverence for the religious context in which she was raised. The research practice that informs much of her work, however, also examines American Christianity’s periodic use of its influence to dangerous ends: to coerce believers that one group of people, one gender or one race, could be superior to another. Despite her respect for religion and personal spirituality, Williams’s work considers the inconsistency of how a holy scripture meant to offer lessons for the greater good could be adopted to justify dangerous power dynamics in its doctrines governing social and political life. One of the artist’s references, Robert P. Jones’s White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (2020), discusses the Church’s condoning of slavery in the nineteenth-century south and — allegedly in service of a just society — its resistance to Civil Rights. Not dissimilar from white supremacy’s fallacies of what constitutes American freedom, Jones furthers this connection: “Mapping the experience of Civil War defeat and the resurgence of white supremacy onto Christian conceptions of crucifixion, redemption, and salvation,” he wrote, “[white southerners] dubbed this new period ‘Redemption.’”

From biblical accounts of torture to the racism her father faced in the American South where he was raised, many of Williams’s works point to places and individuals behind these narratives and the realities they create. In “The Ghost in Me” (2020–21) at Murmurs in Los Angeles, the artist’s first total installation included several heirlooms in the form of masks and other “souvenirs.” In Night Hag (2020), a face mask congealed in wax, soap, and red lipstick, mixed with a translucent material to form a red halo, is set within the aperture of a black frame for a stage-set lightbox. This object, for the artist, recalls the account of her father growing up in Louisiana, where he would watch Poseidon’s Parade. In this then-segregated annual event in New Orleans, white men wore blackface and afterward chased onlookers in the streets, leaving Williams’s father to hide under a house to escape. That he was too young to really understand what these agents of racism had done calls to the kinds of hidden, underlying truths her work engages.

The motif of hiding in plain sight emerges in each of the nightmarish dreamscapes Williams spins. Frequently, objects are submerged and trapped, only partially visible beneath a skin of wax or resin. Her installations, subdued in shadows pierced by the glow of backlit assemblages, are laced with haunted realities in physical space: yellow flower-patterned wallpaper that might drive someone to insanity in a room of rocking chairs (The Conversation, 2020); or in Precipice (2020), a set of mirrors reflecting the backside of a frenzied, smiling cartoon pop-up, its surface eroding in a hardened soap enclosure. Not unlike Betye Saar — whose iconic Black Girl’s Window (1969) and choreography of assemblages provide a rich historical lineage for Williams’s intricate constructions — the artist conceives her stage-like installations with stories of childhood innocence, strong ancestral ties, and female protagonists, but always stained by racial or gender-based injustice. While symbols from these stories recur throughout her work, the lexicon they form does not require pinning down a source. Instead, her work stands on its own, evoking a mad archive or an abandoned home, with a spectral presence deeply felt beyond language. In the Murmurs show, a work titled Church Organ (2020) includes two masks submerged in a backlit block of wax inset in a wooden cabinet reminiscent of one in her grandmother’s home — “a kind of diasporic vessel” for Williams. Through the work’s plays of shadow, silhouette, light, and entrapment, these buried objects are charged with an aura of protection and safety.

Importantly, Williams refuses to repeat depictions of violence. She was one of the first among a wave of younger artists to revive an interest in abstraction or conceptual practices, perhaps as a strategy to resist this trap — and as a rejection of institutional pressure to offer up the self or one’s trauma as a work’s material. Instead, her practice surreptitiously eliminates the distinction between interior and exterior world by embodying, both literally and figuratively, the impact of power structures that violently abstract the human condition according to their own image. While reflecting on and seeking to deconstruct her own social identity, Williams’s work moves beyond the self to what she describes as “uncovering the darkness of American history to better understand the seed of its ongoing nature.”