As art institutions adopt performance-based practices, artists, curators, and archivists are faced with new considerations about how to classify and care for the objects that structure or are interacted with by performances. How do makers and audiences perceive these sometimes sculptural and other times prop-like things? How does the spectator’s relationship with these objects of performance change when performers are absent?

As much as Kenyan-Canadian performance artist Brendan Fernandes is known for bringing dance into the space of museums and galleries, his work is equally concerned with what happens when bodies are absent from these spaces. Early in his career, Fernandes’s projects explored how Western museological practices separated masks and cultural objects from the animating bodies of African performers. For instance, in From Hiz Hands (2014) Fernandes reanimated masks in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art by recreating them as neon sculptures that gently pulsate Morse code. Giving silent language to these objects was a way of returning persona to them, allowing them to express their detachment at street level.

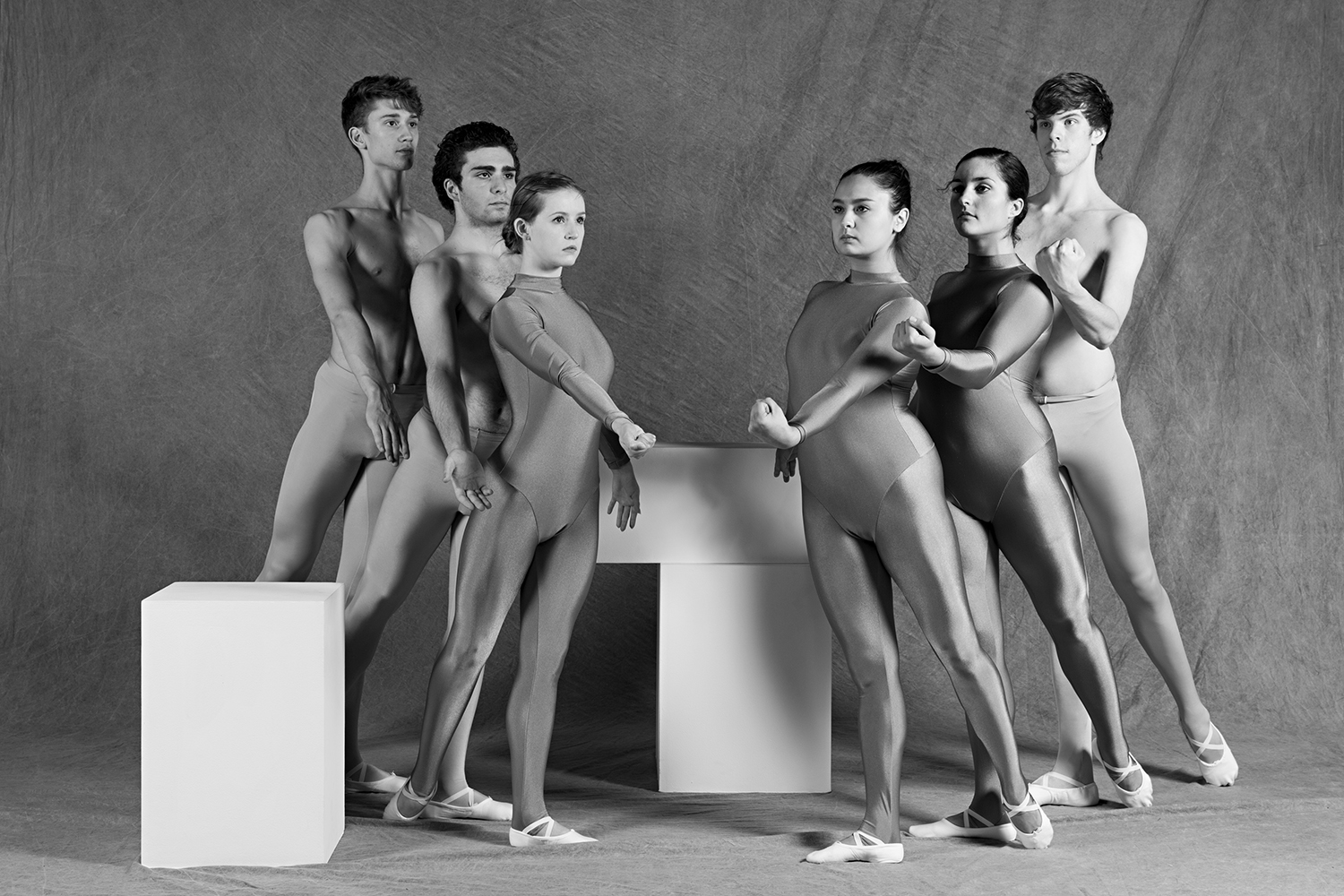

In the recent 2019 Whitney Biennial, Fernandes presented Master and Form II, an architectural installation and dance performance that again examined the relationship between object and performer. Through a masterwork of generosity and coordination on the part of Whitney Museum staff and Fernandes’s team of dancers, the Master and Form II ballet was performed a total of one hundred times throughout the run of the biennial. For the remaining two thirds of the exhibition’s open hours, the installation of scaffolding, ropes, and custom walnut devices were activated by audio recordings of dance rehearsals. The effect was ghostly. The sounds of the disembodied dancers’ movements playing over the motionless installation called the absence and invisibility of the performers into question.

Fernandes’s 2015 video project Authority Inside also explored how to manifest the absence of performers’ bodies. Created in the archive of the Justin and Elisabeth Lang Collection of African Art, the video is a duet performance by Fernandes and dancer Aria Lara Wilton. However, Fernandes and Wilton never appear on screen. Rather, they perform a choreography from behind their respective cameras. Their presence is witnessed entirely through the body’s index on the camera: the staccato motion of Wilton holding the camera while on pointe, and the slow panning motion of the archive’s shelves as Fernandes rolls them from off screen. The effect is haunting and suspenseful, calling to mind the close-ups and handheld effects of horror films.

Like the audio recordings of dancing bodies in Master and Form II, the trace of the body in Authority Inside changes how the viewer experiences the objects visible. Through the absence implied by Fernandes and Wilton’s disembodied gestures, the objects are framed to be seen as haunted. Not by these camera-wielding intruders, but rather by their own unsettling place within the archive. There, at a great distance from their communities of origin and their intended cultural purposes, the objects in Authority Inside quietly announce their out-of-place-ness. Fernandes describes this state of being out of place as “queer.”

Queer, not in the sense of being of an identity, but queer as in the failure to be identified. The objects in Authority Insideoccupy a queer space in this sense. They are at odds with their surroundings. Master and Form II might similarly be considered a queer space. The work is first and foremost a ballet transposed to the gallery. When performance enters the art museum a host of new collisions arise along the borders of “bodies” and “objects.” Our definitions of “person” and “thing” become complicated. We begin to question where body ends and object begins, and the consequences of how we define each. But Fernandes’s intent isn’t to harden a definition in either direction. His work is to make us aware of how easily these lines can be redefined. Queerness, for Fernandes, is about newness — about manifesting possible and desirable futures in the here and now, however out of place they may seem at first.

To this end, Master and Form II strove for ambiguity. Fernandes writes: “The space of my installations oscillate to become many things. A space to dance in, a space to gather, a space to contemplate. All this happens and is affected by the ways bodies interact, use, and take up the space. In Master and Form II, when the dancers activate the installation, the objects become props and the installation a set. For the dancers, the objects oscillate between being supports and burdens as they are challenged to endure positions held within the dance. After they leave, the devices become art objects again: things that cannot be touched. I find this to be an interesting space. A queering where the objects are one thing at one time and another in a different time. I like the undefined space these objects occupy, because it suggests that other spaces in which we lead our lives might also be open to such redefinition.”

In Fernandes’s work, the belief that rules and behaviors can be rewritten as simply as bringing together a group of collaborators is a powerful center point.

However, Fernandes cautions, “It becomes more complicated when dealing with museum rules and standards. At the Whitney during the biennial, for example, the dancers were only allowed to touch the sculptures while dancing and as soon as the piece was over they couldn’t anymore. Patrons to the museum are never allowed to touch the pieces. When there are no dancers present the installation becomes a space to walk through and gets viewed in the traditional way of objects in a museum. When dancers are in the space there is a new stance adopted by the audience. They position themselves as if around a stage and view the piece from a distant vantage point. In my work the audience is just as much a part of the work as the dancers. The expectations and behaviors that museums and galleries have instilled in us is the target of so much of my work. Without fellow bodies embodying these notions and being challenged by the work to question these together, the projects would be meaningless. I believe the spaces that I create can be meaningful in many ways. When dancers activate an installation or when they are void of them, the spaces themselves still operate and give meaningful, contemplative, and evocative experience.”

Here, Fernandes explains that how the audience interacts with his work — how their behavior changes when performers are present versus when they are absent — is an important part of the work’s equation. If audiences are willing to take stock of their own behaviors and locate in themselves what rules and definitions they are abiding by, his project’s ambiguities become facets of resistance.

Fernandes’s current solo exhibition, “Contract and Release” at the Isamu Noguchi Museum (Long Island City, NY) is a study in such ambiguity. Hosted within the museum’s collection show, “Noguchi: Body-Space Devices,” “Contract and Release” is a performative and architectural intervention that takes as its main point of reference a set that Noguchi designed for choreographer Martha Graham’s Appalachian Spring. Raising the question of what makes an object a “prop” versus a “sculpture,” the exhibition includes the original set borrowed from the Martha Graham Company and its iconic plywood “rocking chair” that doesn’t rock. Across the room from this plywood original is a bronze-cast and plinth-mounted copy that Noguchi produced in his studio. Its heavy, metallic immobility insists on its status as sculpture. Last, there is Fernandes’s addition, a series of rocking chairs designed collaboratively with architect Norman Kelley, dispersed by performers throughout the space. Finally given the ability to rock, these chairs also oscillate between “sculpture” and “prop” as performers activate them with poses from Graham’s repertoire.

As Fernandes explains, this duality between “sculpture” and “prop” has consequences: “An object made for a performance that is determined to be a prop may be destroyed at the end of an exhibition. The assumption might be made that resources will be available to recreate the object in the future. Alternatively, an object made for a performance that is determined to be a sculpture might be acquired by a collection and, like masks separated from communities, restrictions may be placed on its future use. Further, props and sculptures are insured, packed, shipped, and taxed differently according to definitions that are out of the hands of both artists and museums. In Master and Form II for instance, dancers were restricted from climbing the installation any higher than two feet off the ground or else a different type of insurance would be needed for the object. Similarly in “Contract and Release,” insurance for the sculptural chairs would only cover damages if they occurred outside of the scheduled performance times.”

The performers’ presence shifts even the administrative status of the objects. In “Contract and Release” with the Noguchi Museum and Master and Form II with the Whitney, Fernandes collaboratively broaches the question of what performance objects mean without the performer. The question remains open-ended. But activating the question helps to propel the work forward. On a practical level, the ambiguities he raises mean problems to be solved. They mean administrative excitement: the frisson of the unclassifiable and the possibility of being the first to enter something new into a system of understanding. In this way, this throughline of Fernandes’s work plays deeply with museological tendencies. Collaborating with museums and institutions, the projects, even in the absence of performers, continue to question the boundaries of personhood and objecthood. They remain open, suggesting we should do the same.