Hans Ulrich Obrist: I know that you started very early and were a wunderkind of sorts. So, I wanted to ask about your first epiphany. You suddenly had a revelation; you became an artist. How did this occur to you?

Braco Dimitrijević: I grew up in an artist’s studio and had all these artist’s materials at hand and also a constant need to express myself through visual messages. It became more rational as time went by and at a certain point I stopped painting in order to do different works, which later proved to be very early conceptual art. One of the first works I did was The Flag of the World. You know, every boat is supposed to have a national flag at the bow but for me it seemed absurd to have to change flags when crossing territorial waters. Therefore, I decided to replace the national flag with something that can serve as a universal sign for all territorial waters and different seas. I replaced it with a cloth for cleaning brushes, and this was the artist’s flag.

HUO: Can one say that this flag, which you made in 1963, also marked the beginning of your outdoor interventions?

BD: Yes. This was a very early intervention into something that is, let’s say, official vocabulary: this work replaces an official sign with an individual, alternative sign. This was repeated some six or seven years later, with the big photo portraits of “Casual Passer-By.”

HUO: “Casual Passer-By” represents another epiphany where you had enormous photographic portraits of people who are usually not in the limelight, and you placed them on very prominent locations in different cities. What triggered these everyday or casual monuments? Was there a moment when the idea suddenly came to you?

BD: When I realized that painting was not my medium, I also realized that I would do some kind of scientific research. As you know, I studied physics and mathematics for two years. However, I then realized that my methods were really not scientific and I returned to art. I wanted to create a work of art that would somehow analyze human behavior. The “Casual Passer-By” photos were a trap for a certain behavioral reflex whereby spectators would be likely to automatically identify the subjects of these large portraits as important political figures or media celebrities, which they weren’t. In the galleries I exhibited smaller framed pieces with the photographs stating that they were casual passers-by, so that spectators would learn that they had made a wrong judgement about these large photo portraits.

HUO: Could you say something about the famous London Casual Passer-By piece you did 38 years ago?

BD: When I arrived in London to study at Central Saint Martins School of Art, I realized that the semiotics of the urban environment differs from country to country, or from one social system to another. Also, I realized that probably the best way to insert the “Casual Passer-By” in London was to build a monument, because at that time London had many more monuments than large photographs. Later, as technology developed, the billboards of Western cities were invaded by large images. The first Passer-By in London was a monument dedicated to a passer-by named David Harper that was installed on Berkeley Square, in Mayfair, at the heart of London. Actually, the works that preceded the monument were the memorial plaques. Walking around Soho, which was just behind Saint Martins, I would notice plaques stating that some writer or musician had lived in a certain building. I realized that the explicit message — for example Hector Berlioz had lived in that building — is that genius had lived in that building. The implicit message of all the buildings without memorial plaques was that genius had never lived there. And we know how often history is wrong. I wanted to correct this situation. I started putting up these plaques dedicated to passers-by on different buildings, stating that they had lived or worked there.

HUO: You were born in Sarajevo and were later active in Zagreb. When I visited Zagreb, I realized that in the ’60s there was a very interesting and dynamic avant-garde there. I am referring to the Gorgona Group and artists experimenting with film, etc. You were in Sarajevo and Zagreb and also Belgrade, where at more or less the same time there were very interesting energies popping up, and I was wondering to what extent that context was important for you?

BD: When I became an art student in Zagreb the artists you mentioned did not exist on the art scene. Maybe in the early ’60s they had some private activity that had not left any traces in cultural life. Most of them were present as traditional draftsmen or painters, except Julije Knifer, who was a radical hard-edge painter. In contrast to them, the Zagreb neo-constructivist artists from the EXAT 51 group, like Ivan Picelj or Aleksandar Srnec, constituted a real opposition to official art and they created an opening for the younger generation. It was only several years after my shows in London and Düsseldorf, and after Documenta 5, and especially after my solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1973, that they started speaking about their secret meetings. It was only in 1977, when conceptual art was already well established, that Nena Dimitrijević, my wife, put on the first-ever Gorgona exhibition and showed their work to the public. Actually the influence was reversed; my public activity and the museum show in 1973 encouraged the Gorgona people to talk a bit about what, until then, had been a hidden, private activity. As the Belgrade critic Jesa Denegri put it, “Gorgona would never have existed without conceptual art.”

HUO: So one can say that it was all very much an underground scene. Did you have contact with Warsaw, or were you connected only to Belgrade?

BD: I was already exhibiting in London when Belgrade artists started being active. When I moved to London I met some people from the Foksal Gallery. But really, in the late ’60s I had no knowledge of conceptual art in other Eastern European countries. In 1971 Nena and I did a show entitled “At the Moment” in an alternative space in Zagreb. After a gallery show in 1969 I chose an ordinary entrance hall of an apartment building in the center of Zagreb and sporadically made exhibitions there which would last a few hours. “At the Moment” was a group show with artists like Giovanni Anselmo, Joseph Beuys, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Sol LeWitt, Barry Flanagan, Laurence Weiner, Jannis Kounellis, Ian Wilson, etc. There were about 25 artists in all and the show later travelled to Belgrade. The review of the show by Studio International in London triggered some reactions and letters from artists in Czechoslovakia and Poland. The Moscow conceptual scene developed in the ’80s. I had no contacts with any of the Moscow artists at the time. For instance, I met Kabakov, a pioneer of the Moscow scene, during the “Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition, in 1989, and we immediately became friends.

HUO: Who were your influences when, in 1963, you started to create your first conceptual works? Were there people from the avant-gardes of the early 20th century who inspired you?

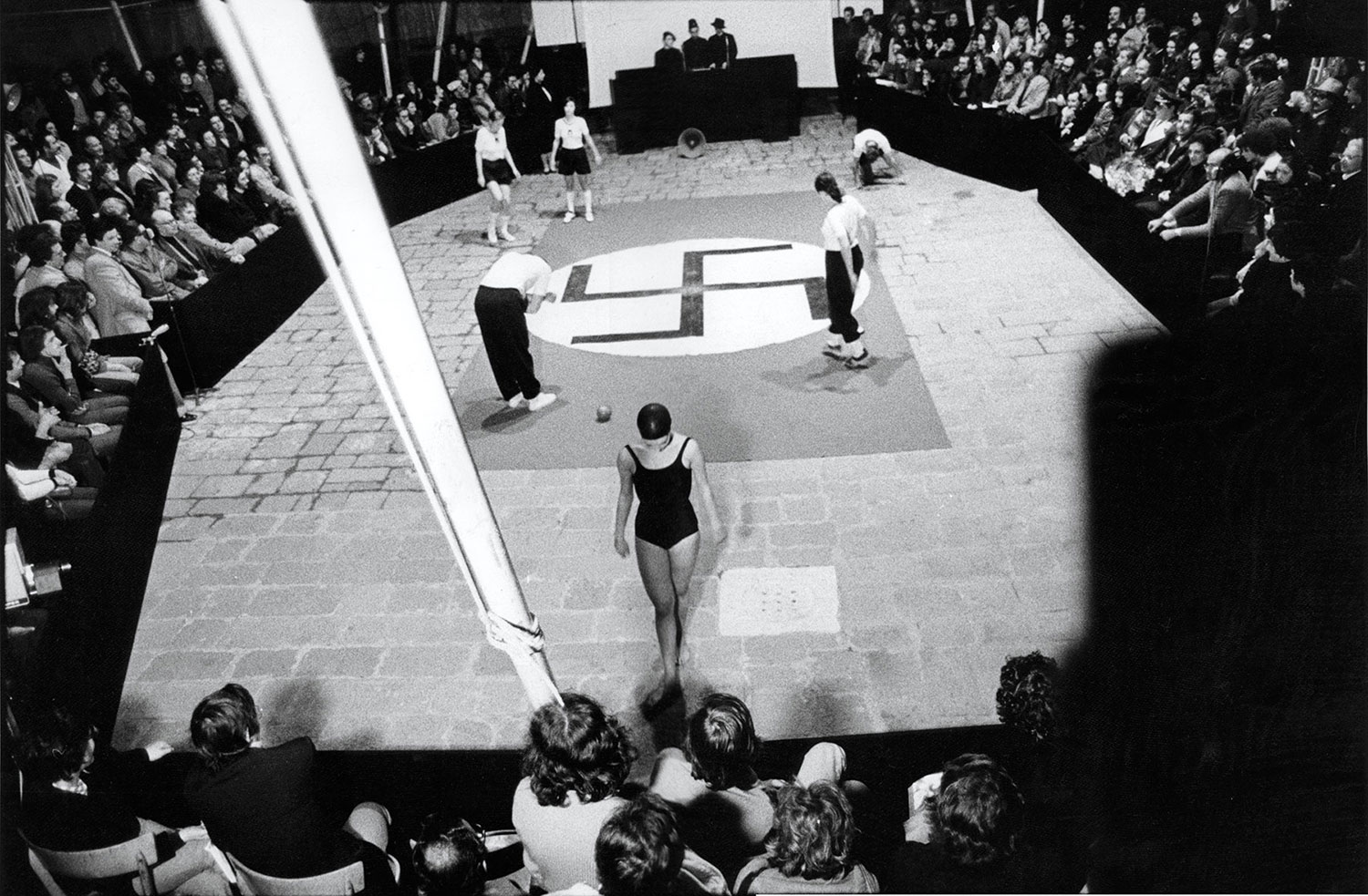

BD: From my early childhood I remember the names of Duchamp and Picabia. I just recall these artists as doing something interesting but that I did not understand fully. Later, when I was 15 or 18, I went back to reading a book on Dada that I used to leaf through as a child, and I realized what their work was about. In fact, the first avant-garde work I saw was in the domain of theater. I saw a performance by The Living Theatre in Sarajevo in 1965. In this Neo-Baroque gilded theater the actors were pushing each other and spitting at the audience. There is also an episode I recall, a totally casual meeting with Lettrists and Situationists when I was visiting Paris. In late 1967, somebody in a café in Saint Germain told me to go and see a screening by the Lettrists and Situationists in Rue Vivienne. The screening included scratched films by Isidor Isou and Maurice Lemaître.

HUO: So that was your contact with Lettrism?

BD: Lettrism, yes. Also some of the Situationists were there because they were all mixing together. At that time I think they hadn’t even heard of some of the Russian constructivists like Malevich, or other big names. There were no signs on the horizon of minimalism and even less of conceptual art.

HUO: We clearly have another epiphany, which is your invention of ‘Post-History.’ We discussed this at our very first meeting, when I met you in Paris in the late ’80s. In another interview, you say that actually the whole idea for the Tractatus Post-Historicus had started already in the ’60s, in 1969, when you said, “There are no mistakes in history, the whole of history is a mistake.” So, could you tell me a little bit about this revelation of the Tractatus Post-Historicus?

BD: Again, there is a link to some of my childhood experiences. Thanks to my parents I knew Ivo Andric, a friend of my father’s who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. I also met Jean-Paul Sartre as well as some legendary figures from the Resistance. However, my parents had a very open attitude, they would talk to me about many different things, and I realized that people who were not famous or public personalities could be just as interesting. So I started reflecting on this mechanism which promotes certain ideas or certain people and makes them famous while others remain anonymous. All this led me to the conclusion that history gives a very mutilated and simplified image of the past.

HUO: And how did you then develop this into the book Tractatus Post-Historicus published in 1976, which is a kind of a manifesto?

BD: It is a manifesto. I started reflecting further on history and formulated Post-History as a platform for multi-angled viewing, where a multitude of truths coexist and where a plurality of subjective truths exist without denying other subjectivities. Historical method is based on the elimination of the facts that do not fit into a linear narrative. I think that the past is a lot more complex than recorded history and demands a more complex approach. I have this saying that the whole of history is not as rich as one second of post-historic time.

HUO: You started to do installations related to the Tractatus Post-Historicus. So can one say that it was not only a manifesto of a verbal nature but also a trigger for a new type of work?

BD: Right. It is very important to me that things happen in real life — even for just a few seconds, so as to establish a new model for a possible reality. I could easily have done photomontages of passers-by portraits on façades, but instead I struggled and waited sometimes up to two years for the real photograph to be hung in public space. Just before I wrote Tractatus, the “Triptychos Post-Historicus” works were gestating in my mind. I was doing a show in the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach with Dr. Johannes Cladders, who as you know was the co-curator with Szeemann of “Individual Mythologies” at the 1972 Documenta. I was preparing a solo show in 1975 with him and for the first time I borrowed a museum item in order to make my work. And so this idea was already there. For example, with Cladders I made a contract that from then on, for six months, this same work would be exhibited as a bust of Max Roeder and for the next six months would be a work of mine under the title This Could be a Masterpiece. He even purchased this work for the museum. So suddenly this work, which had been in the museum collection for 50 years, started having a double life. And for me this proved the possibility of parallel existences and multiple truths. In 1976 I made my first triptychs with Kandinsky, Mondrian and Manet at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. I chose the paintings from different periods in order to break up any linear narrative, to question the dogmatism of style and Darwinian linearity in the presentation of art. Later I did “Triptychos Post-Historicus” installations with masterworks from many museums around the world including Malevich, Turner and Cézanne at the Tate Gallery, Léger and Picasso at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Chagall and Picabia at the Guggenheim Museum, Leonardo da Vinci and Piero della Francesca at the Louvre and Van Gogh at the Musée d’Orsay. If Johannes Cladders hadn’t supported that very first appropriation of an original artwork in 1975, I certainly wouldn’t have given up, but it might have taken a lot longer.

HUO: In 1998, your installations with living animals suddenly became global news when you did this show in a Paris zoo with lions, tigers, crocodiles and many other animals. I think it was seen by one million visitors and was even featured on CNN. So, in terms of this idea of making things public, to quote something Vito Acconci once said, “Things are not just naturally given as public, you make things public.” It seems that this was another kind of breakthrough moment.

BD: Yes. Actually do you know this story that I wrote when I was 20? The story about two artists? One becomes Leonardo da Vinci because the king finds his dog in his garden and the other disappears from human memory. Well, this story is significant because it illustrates how chance plays a role in the recognition of some ideas. Just as in those early works where I asked people to sign the milk splash on the pavement. I have always insisted on this idea of interaction in bringing the artwork into existence. For a work to exist it is not enough to make it; it exists only if somebody sees it. The minimum number of people for enabling art to exist is two: the one who makes it and one who perceives it. The artist who does not struggle for his vision is not an artist. I remember when in 1981 in London I proposed to Leslie Waddington to have living peacocks wandering around his gallery in Cork Street where paintings by Picasso, Léger, Monet and Cézanne were exhibited. He agreed. So his sensibility and responsive attitude helped this idea to become a reality. Later I made other pieces with living animals and finally the show in the zoo on a very large scale. For my 35th birthday I played piano to some elephants and entitled that piece Last witnesses of another logic. After that I did the first piece with lions, then a show in the Turin zoo and finally this mega-show in Paris in 1998.

HUO: In interviews you mention the speed of sound, the speed of writing, the speed of spectacle. You even did a show in a Vienna museum with Lorand Hegyi, with the title “Slow as Light, Fast as Thought.” That ties in with your past as a ski champion and your comparison of creating a work of art with a 100 kilometer-per-hour descent. Could you say something about velocity?

BD: I think chance is hidden determinism. Things are connected. I’ll tell you an anecdote known to very few people. When Alighiero Boetti was buying an apartment for his daughter Agatha she was hesitating between Rue de Charonne and another street in the neighborhood. When they stepped out of this building in Rue de Charonne she was saying, “Daddy, I can’t decide.” And he was looking at the façade and spotted a memorial plaque on the building and said, “If this place was good enough for Roger and Suzanne Clauzade to live here in this building, it should be good enough for you.” And they decided to buy the apartment. Later he realized that the plaque was a piece of mine. Even if he had known me and my work for 20 years and knew about the memorial plaques that I installed in Turin and elsewhere, that work still had enough persuasive power to make them choose that building. Now, to answer your question about velocity. I think that people who are in the visual arts and who are capable of expressing themselves either by exhibiting art works, as is the case with curators, or by creating art, as is the case with artists, have a great advantage. I recall a comment from the 1990 Venice Biennale when a critic told me that my work is “extremely economical.” If a work is economical there is nothing that you can add to it, and there is nothing that you can take away from it. Good works of art are axiomatic. This economy of language enables the artist to communicate fast. So if you are standing in front of a painting you can perceive it in a second. If the work is good you can stay for half an hour, or in some cases you can come back every now and then and think about the real content of this thing that you saw in one fragment of a second. So, in a way, it is a privilege of the visual arts to communicate in this way. When I mention skiing downhill at 100 kilometers per hour, I am talking about quick and intuitive decision-making. It is like when a performer has to decide his next move or when Tadeusz Kantor was directing his pieces. He was also a good friend, someone I admired enormously, and I saw him directing many times. I think he would modify the piece if he saw somebody slightly change the position of his foot, so the whole performance would probably take a completely different direction. In visual arts, we basically come with a proposition and that proposition can, on a certain level, be absorbed immediately. However, I think the reason that I juxtapose everyday objects or the fruits of nature with paintings is to trigger a sense of the multi-layered nature of all works of art and to indicate that there is speed but also depth. That is why I use the metaphor of downhill skiing.

HUO: One question about memory. You have worked with memory in your photographic pieces. From 1972 to 1977, there is “This Could be a Place of Historic Interest,” the photographs of landscapes, interiors and urban scenes, with the words “This could be a place of historical interest” printed under each image. Could you talk a little bit about the role of memory in your work generally?

BD: I think there is a kind of genetic memory which pushes us to do certain things that are beyond the rational. We rationalize them later. For instance, these almost random snapshots of internal and external locations devoid of human presence are related to the subjective experience and the subjective reading of every individual that can be triggered when they see any of these images. I think the biggest treasure of all is human memory and then, when you sum up individual memories, you come to something which we can call a common past, common knowledge or even common experience. Memory is a factor that makes us do things in different ways. Being an optimist, I think that every creative individual is somehow trying to make the environment better or, in other words, to improve the conditions of memory. The whole idea of Post-History has to do with respect for the multitude of memories. The multitude of memories is what constitutes the complexity of civilization.

HUO: I was wondering about your unrealized projects. Projects which were too big to be realized. Utopias.

BD: For instance, one of my longest running projects, in terms of asking permission, was to exhibit in the cave at Lascaux. It went on for almost 20 years. Finally, in 1993, I was given permission to create and show by candlelight 12 paintings in the presence of 12 people in the cave of Lascaux, one of the most impenetrable of all historic monuments. It was like a kind of resurrection of Neolithic art. So my utopian dream is that we should reach a phase where all the gifts and all the different talents that every individual has would come to an optimal context of realization because, for instance, at the dawn of civilization, as at Lascaux, the people who had a gift for hunting hunted, men who had a gift for painting painted, and those who had a gift for lighting the fire would light the fire. In a way, my dream is to have the situation where all these activities would melt together and where those who have the capacity and talent for making certain things would have the opportunity to do them and make them public. It would mean that we had entered the Post-Historic era.

HUO: Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a short book of advice to a young poet. What would be your advice to a young artist?

BD: Just to listen to himself and to find a good friend who can help him to show his work. Beauty has power, and every picture turns into energy.