Manifold intentions define portraiture in painting today: to interrogate the portrait’s capacity to frame the dynamics of identity construction and politics; to challenge the role of the depicted body as a subject in figurative expression; to define the importance of the stage as a backdrop for the portrait; to convey our viewed and experienced relationship to the contemporary self and digitalized culture. Three painters from diverse backgrounds and generations — Jordan Casteel (b. 1989, USA; lives in New York), Tomasz Kowalski (b. 1984, Poland; lives in Warsaw) and Birgit Megerle (b. 1975, Germany; lives in Berlin) — discuss with Martha Kirszenbaum the relevance of the portrait and the (mis)uses of representation, addressing the position of the constructed image in the visual culture of our contemporary societies.

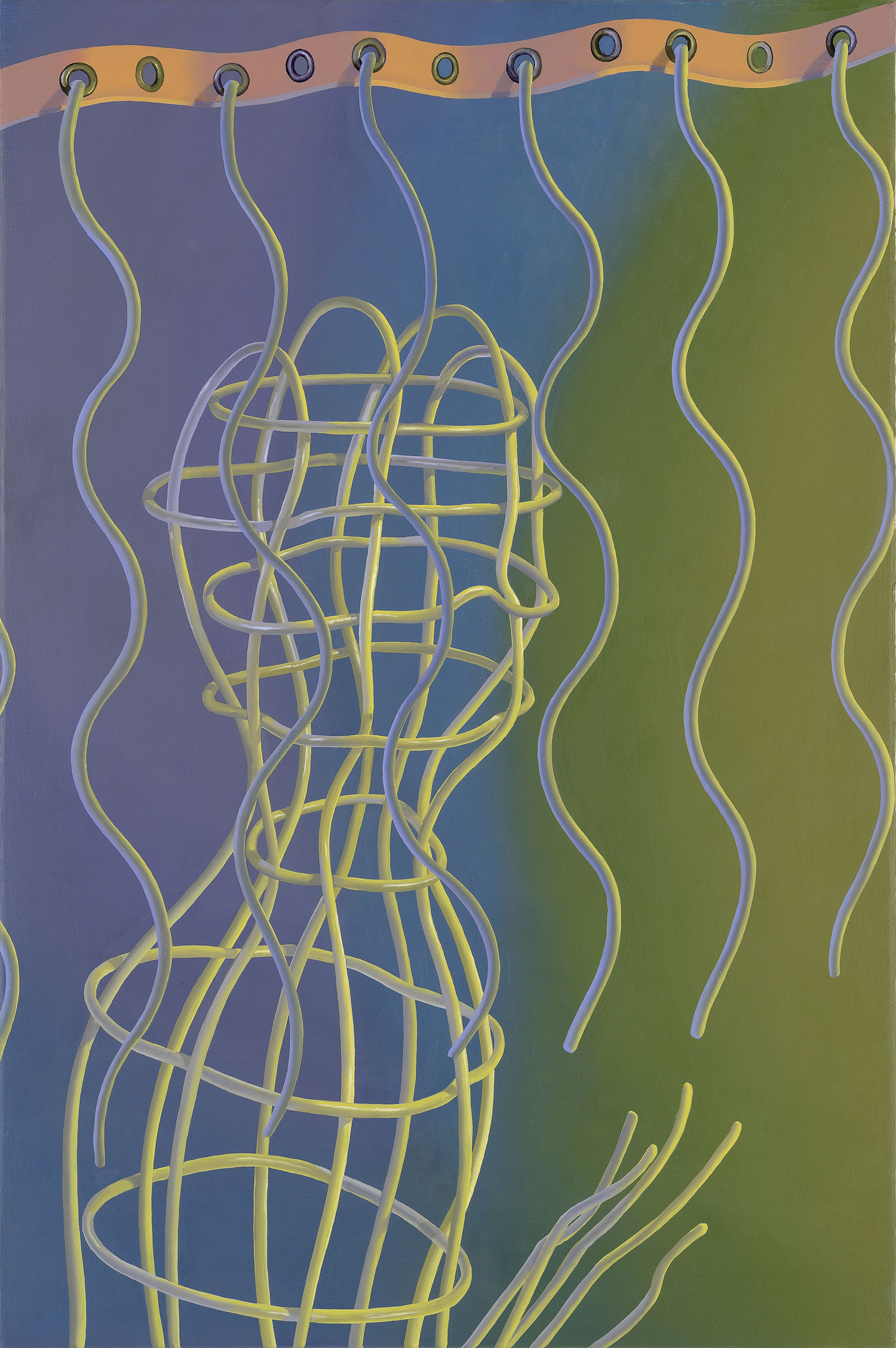

Martha Kirszenbaum: I would like to start this conversation by analyzing the role of the depicted body as a subject in figurative expression and contemporary portraiture. Birgit, your portraits have often featured female figures, poised with determination and a certain artificiality (Living Currencies, 2015, or Beauty Fields, 2015) while the central subject of Jordan’s work is black men in intimate situations, and Tomasz’s paintings depict vanishing, de-humanized figures recalling mannequins and dummies, inspired by Polish-Jewish writer Bruno Schultz.

Birgit Megerle: I mainly take photographs of people from a certain context, like artists I collaborate with or friends whom I ask to wear my hand-painted dresses to model for a portrait. These photographs serve as a reference or a starting point for my paintings. My recent show at Galerie Emanuel Layr in Vienna was rather about appropriating mediated images, and I got interested in painting a woman having a leading role in public life or politics.

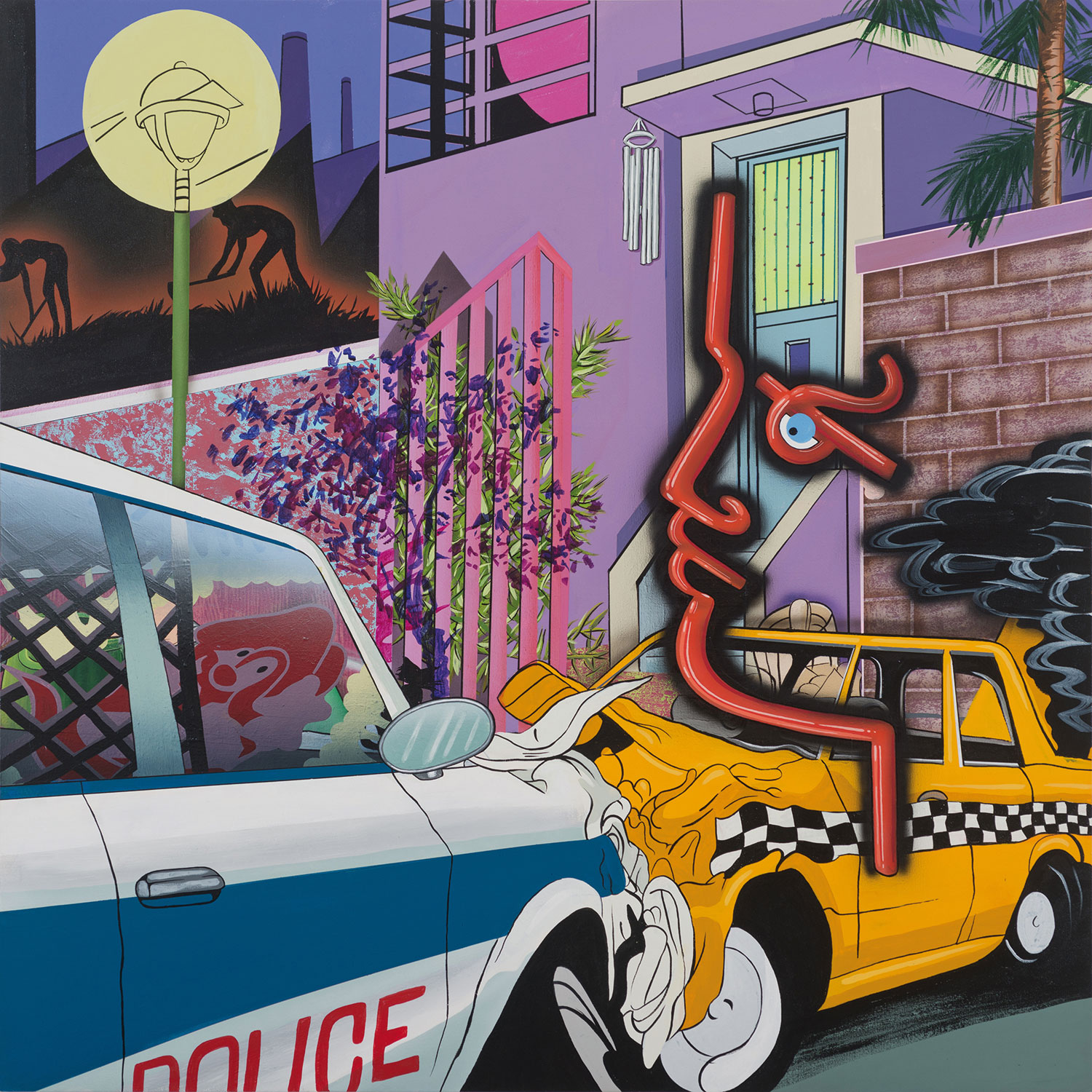

Jordan Casteel: Figurative painting to me is an opportunity to bring to light what is often unseen. I hope to interpret and sincerely portray what it means to be a black man today. The home becomes a stage for the subjects, in that the home is an emblem of comfort. Through comfortability, the subjects become vulnerable in a sharing of intimate and often private space. These men, often in repose or relaxed, are surrounded by evidence of themselves: books, clothing, furnishings — waiting to meet their eyes with the viewer’s. For example, in the painting of Ato, he is seated in a fetal position on a chair with fraying edges — clearly full of history. The figure acts almost as a chameleon, as his skin color mimics that of the chair. His blackness is more a result of our projection than a reference to actual skin color. His gaze matches the viewer, maintaining his awareness of the returned gaze. Beside the figure is a picture of a woman. Who, specifically, the viewer does not know. However, that image of a woman beside him clearly holds a certain level of importance. Each detailed element in every painting feels essential to the subject itself, helping to shape a vision of who this man might be. In the wake of such public continued violence against black men, it is more important than ever to contribute a vision of blackness that shows the complexities of black men instead of reducing them. These paintings address the broader scope of the human experience. Whether it is a solo figure demanding intimate attention, or multiple figures leading us to ask who they are in relation to each other — each subject is asking to be seen through an empathetic lens.

Tomasz Kowalski: Finding different ways to represent a human being in painting has always been my central interest. The feeling of “de-humanization” that you get when you look at my works comes from an idea of showing the body detached from its inner traumas, but depicting these inner traumas as a landscape. In my paintings, the earthly being is usually placed in a virtual space of its mind, being somehow turned inside out. This space of mind serves as a stage for dummies — like protagonists doomed to an endless play with the given props.

MK: How relevant is the canvas as a backdrop or a theatrical stage for the depicted characters in your respective practices? Do you conceive it as an organic space or as a constructed entity? Jordan — the emphasis on clothing or costumes, and particularly iconic clothing related to hip-hop and black culture in your paintings seems reminiscent to theater as well. Tomasz — your practice evokes the particular significance of puppet theater in Polish culture, and Polish theater in general. Birgit — your canvases have been literally used as backdrops for different performances, including at the New Theater in Berlin, and were therefore physically animated.

JC: The canvas for me serves as a boundary and construct that has an opportunity to mimic real life. I see the edges of each canvas as edges that can be pushed up against and challenged by the depicted subjects. The subject often matches the size of the canvas in the scale — toes pushing up against the edge, drawing attention to the closeness of the subject and its wall. In thinking of theater as a literal stage to share and engage with stories, the canvas undoubtedly is similar in its practice. Every aspect of the “stage” is considered. For me, my stage is always related to the domestic. By placing men in their homes, we are able to think about the items they own as “props.” Clothing or “costume” is often a reference to personal style. Throughout history, clothing has served as a literal casing. In my paintings of the black male nude, I am directly challenging the barrier clothing creates for black bodies. I have found that clothing on a black male body can in fact create a distraction for a viewer in that it comes with so many assumptions about race, class and culture. Because the important conversation for me is about humanity, vulnerability and intimacy, removing the clothing on those singular figures was paramount. The clothing appears again in my paintings with multiple figures because the relationships between the figures become the center stage — leading us to ask what their relationship is to one another. For example, in the painting Ashamole Brothers the clothing is purposely generic in comparison to everything else in the room. The basketball they share, the drawings in the background, and the colors are much better references to who these men are. They are not hip-hop or emblems of black culture; they are young brothers with unique interests of their own.

TK: Very often the objects are somehow “stepping out” of my canvases, creating, together with the paintings, a complex stage-design-like sphere. Still, I have a certain affection for two-dimensional objects expanding into a deep, broad space, similar to the traditional canvas or an iPod screen. Due to the character of the processes of memorization run by our brains, when still images are created out of our feelings, the picture on canvas can in fact appear as more realistic to the viewer than a live event.

BM: It was exciting to see what happens when my paintings clash with other elements in a theater play like Hotel Moon, presented last March at New Theater. For instance I did not expect that the costumes would refer to fetish-inspired clothing. Working on these paintings felt a bit like adapting another identity, not unlike the actors in the play. For a while I used singular figures freestanding in the exhibition room. I noticed that it seemed like a good method to animate the abstract pattern paintings that I produce from time to time, and which were installed on the walls.

MK: I keep thinking about Jacques Rancière and his statements on the depolitization of painting as an aesthetic experience. Could you define the importance you attach to political interpretation of your painting work, and particularly in a context where identity politics seem dominant in the intellectual realm. Birgit, as a female painter, you depicted women invested in our political or cultural imaginations, such as IMF director Christine Lagarde or a young Catherine Deneuve. Jordan, you are a woman of color portraying black males — what does it say about an inverted female gaze, also in the context of racial tensions in the US? Tomasz — do you feel that your works convey a political statement?

BM: Working on the painting depicting Christine Lagarde was something new to me since I felt completely detached from her personality. I wondered how it would feel to portray someone whose political activities are rather alien or felt even contradictory to mine. As I never see my paintings as singular, mere images, they always function within the concept of a show as an entity — so do the abstract ones. It’s more like a mise-en-scène of paintings, photographs and curtains as theater props.

JC: When I began the project of painting black males, the public consciousness about the current vilification of black men was just becoming widespread. But, for me, it was rooted in my own personal life and relationships. For years I had been watching black men around me being portrayed as something different than what I knew and experienced. The world saw those that I loved most — my brothers, my father, my friends, family and lovers — as being less than what they are. As those around me were/are literally and figuratively killed, the urgency to share my lens became more imperative. As a woman making this work, my gaze is that of empathy. I am standing in solidarity with my community that has experienced immense loss and pain. I also recognize, that as a woman creating portraits of black men, I can do nothing more than share my point of view. The paintings are a translation of experience through my hand and eyes as a sister, daughter and friend.

TK: My work is not politically charged, but at the same time, of course, I am aware of the fact that one cannot be a political bystander. I deliberately create protagonists that are humans without an identity, with no hint of definable traits. This being serves as a bare nerve, echoing the anxieties present in the society. I believe that an option for an inner change, which I propose to the recipients of my art, is something of great importance.

MK: Lastly, I am interested in reflecting on your relationship to the portrait by asking how cultural, social and technological elements contour the representation of the contemporary self, specifically in an era of extreme digitalization, of blurring of the high and the low and where networking strategies play a crucial role in contemporary capitalism and culture. How does this environment and relationship to the world reshape the core of your respective practices? Is there a generational component that can be noted?

JC: As a painter I am very much tied to a long lineage of art-historical painting. I am working within a tradition that historically would not have been open to me as a black woman. I work with oil paint on canvas, and my interest lies in subject, color and composition. However, as a millennial, my cultural engagement with new media technologies is constant. Photography has been the primary media that has played a significant role in my work. The opportunity to sit long hours for a portrait was once a practice of the elite who had time to offer. Now, as my generation has little patience for a page to download on their mobile devices, it has become quite hard to engage a subject for longer than an hour. As a result, photography has been a tool in my practice. I go to the most comfortable environments for all my subjects and capture my time with them through hundreds of photographs I take in the span of an hour. Those photographs are then taken back to my studio for me to create an immediate sketch on my canvas. Those moments in time become a loose reference for me as I build each painting. Once the paintings are created, through technology, the possibility of sharing my practice and work is endless. I am constantly in dialogue with others as they are with me through the internet. When you Google “black men,” often the images that appear are in a hypersexualized or criminalized context. I am proactively countering those images by adding layers of personality to people who are being portrayed in a way over which they have no control. My hope is that as a result of the digital age, my deeply personal vision will help to create a new narrative and counteract implicit bias.

BM: Crucial to me is how to appropriate a found image and how the image later dissolves into painterly gestures, dots and patches which overlap the bodies and the background of my paintings. For me as an artist, any kind of performance is an interesting battleground, no matter what mediatization it involves. Seeing and showing “the self” via social media, for me, is a performative action per se. And you always get the most likes on self-portraits — besides puppies and food.

TK: As I previously mentioned, what I try to picture in my portraits is the space of the mind. We can ask ourselves: what are the boundaries of this space in the present world, when the cognitive faculties of a human are expanded by machines and unlimited access to information. Are there still any boundaries of the mind? I guess the answer is no, which makes it more exciting than ever in the history, and the challenge to picture such a space, just thrilling.