On the occasion of the first Berlin Biennale, Flash Art edited a portfolio of texts celebrating Berlin as an art city at the nexus of space, dynamism and futurity. In the aftermath of the 9th Berlin Biennale’s underscoring of the surrender of the city’s creative capital to capitalism, Tess Edmonson asks what’s left of “the Berlin Myth.”

I.

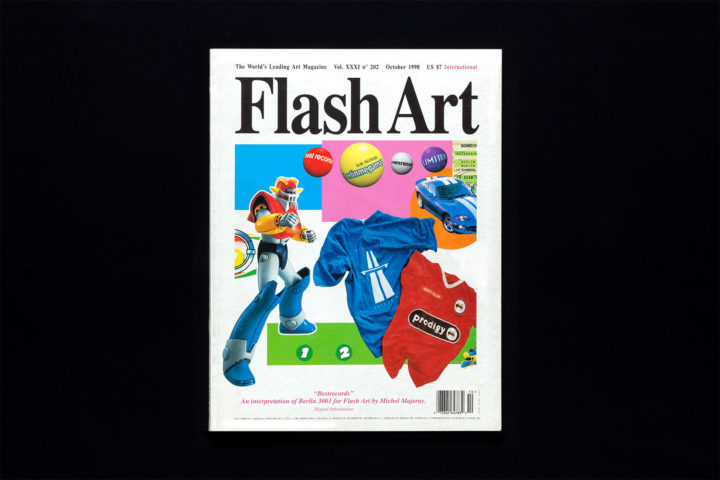

In its October 1998 international edition, Flash Art published a portfolio of texts titled “Berlin 3001”: sixteen pages of essays and interviews on art and the city to mark the occasion of the first Berlin Biennale.[1] Germany was roughly a decade into its reunification, and this portfolio gives witness to interested actors — residents, transplants, artists, gallerists and critics — at work mapping meaning onto the new, mercurial capital. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, “Berlin 3001” disseminates a host of observations about Berlin that, in the nearly twenty years since the issue’s publication, first circulated as truisms, and subsequently as clichés (though even in 1998 these were sometimes presented alongside skepticism about the accuracy or the function of “the Berlin narrative”). They include: the city’s dynamism, its unknowability, its investment in futurity; the proximity of the global to the local; the proliferation of interdisciplinary cultural practices; the pace of urban development, and that development’s attendant unending construction; cultural heterogeneity; artists’ ease of access to private and public space; the city’s incompletion; the weight of its political history; its lack of traditional art-world hierarchies; no standards, no precedents; utopian potential.

Over the course of the seven texts of “Berlin 3001,” these tropes are repeated a few times over. In his contribution to the portfolio, in a text titled “Major Changes,” German curator Waling Boers offers the following description:

Unlike other cities of similar status, Berlin lacks an appropriately trendy and decadent art scene. There is also little evidence of a dynamic economic elite with accompanying collectors, and a prominent intellectual elite has yet to make itself known. Yet Berlin has something else: endless discussions about prospective monuments intended to bring about a moral understanding of its own problematic past; empty spaces that may be occupied by newcomers, known as Einsteiger; re-formed galleries; artists who remain longer in the city than the hanging of their work demands; a young, enthusiastic public; a lively club scene and, to top it all, the Love Parade. [2]

Berlin’s art scene is defined here by the city’s leisure culture, its open space ripe for occupation, and its history of internecine violence.

II.

While many of these observations are still put to use in making sense of the city and its cultural production — and in giving these both value — the material realities on which these assessments are based mostly no longer exist. A short text in “Berlin 3001” by curator Dan Cameron, a regular contributor to Flash Art in the late 1980s and early 1990s, describes galleries “financed on a shoestring budget” that are now among the city’s most moneyed and influential.[3] The neighborhood around Auguststrasse — with Kunst-Werke, established by Klaus Biesenbach in the early 1990s, at its heart — figures in “Berlin 3001” as a central reference point. Cameron writes: “The remarkable proliferation of new galleries on or near the Auguststrasse can be seen as a miniature variation on the mega-expansion taking place throughout the city.”[4] As the artist communities that once populated the area after the fall of the Wall became institutions, as ever in gentrification’s narrative arc, their interests have fallen ever closer in line with those of private capital and the state. The Berlin Biennale, whose venues historically clustered around Kunst-Werke, has been instrumental in this process. In 2017, the area around Auguststrasse is largely the domain of start-ups, cappuccinos and luxury retail.

A particularly dissonant anecdote in Cameron’s text describes a visit to the studio of Olafur Eliasson, established in Berlin in 1995: “The highly improvised nature of Eliasson’s works-in-progress seemed to supply a homemade metaphor for Berlin’s own state of perpetual becoming.”[5] At present, Eliasson’s studio occupies a five-thousand-square-meter former brewery in Prenzlauer Berg, purchased and converted in 2008, and currently operated by ninety employees. Of these, a kitchen staff prepares a daily vegetarian lunch for the studio’s workers. Last year, Phaidon published a cookbook by the studio kitchen, offering 368 pages of recipes and food photography. As part of the first Berlin Biennale, Eliasson presented Ventilator (1997), an electric fan that hangs from the ceiling by a cable, spinning and swinging unsteadily through gallery space. If the lightness of Eliasson’s practice in the late 1990s was understood as a metaphor for the city’s potential for adaptability, for perpetual motion, one wonders what the contemporary fruits of Eliasson’s lifestyle factory could be said to represent.

III.

On one hand, we can understand “Berlin 3001” as a sort of historical miscellany, or evidence of the intellectual curiosities of the era. On the other hand, the notion of Berlin as an art city — at the nexus of space, dynamism and futurity — has ossified around the city and its biennial in a way that little seems able to change. Those meanings are fixed in place even as discourse, art production and material conditions in the city have dramatically evolved.

Of course, these meanings, even as they are delivered in “Berlin 3001,” are coupled with contemporaneous criticisms of their insufficiency. The edition of Flash Art that followed “Berlin 3001” published a rejoinder of sorts: a comprehensive review of the Biennale and its stake in what it calls “The Berlin Myth.” In the text, critic Boris Moshkovits describes the myth as “an emptily dramatic formula that has been bandied about with a surprising lack of criticality in the last few weeks.”[6] Moshkovits is skeptical of the world The Berlin Myth forms in its image: it’s too convenient, too self-interested, not intellectually rigorous; it obscures incompletion as potential, and coheres otherwise disparate (and unrelated) practices. In what might be an evergreen criticism of biennials immemorial, he writes that “putting seventy artists together in an exhibition does not automatically produce content.”[7]

IV.

In an interview in “Berlin 3001,” Biesenbach, a figure whose individual career trajectory is inextricable from what art production in Berlin now means, remarks that “this city is experimenting with itself on a gigantic scale.”[8] One gets the sense that Berlin’s futurity was once linked to public uncertainty over how power would eventually come to be distributed after its disruption during reunification. Even as of its first edition, Moshkovits asks, “Is the Biennale still an experimental field for young artists […] or just another forum for established gallery positions?”[9] What if the experiments Biesenbach refers to have since been exhausted, all proving the same, dissatisfying result — that art doesn’t intervene in the privatization of civic space, but actually accelerates it?

These concerns seem crystallized in the most recent Berlin Biennale, its ninth edition, which opened in June 2016. Curated by New York collective DIS, the exhibition presented the post-internet in high-definition gloss, and cycled through its favorite methodologies, including the appropriation of corporate branding and aesthetics that turned off so many of its reviewers. It moved the exhibition’s central locations away from Auguststrasse and into the city’s former West, away from art commerce and into the domain of regular commerce. Three themes came across in much of BB9’s critical reception: the end of what promise Berlin once held as an art city; the end of the biennial as a critical form; and the end of art, in general. In a review for The Guardian that gained notoriety for the severity — and, in my estimation, the strange deficiency — of its criticism, Jason Farago writes, “This show does not argue for a better art world; it argues for giving up on art entirely.”[10]

To me, BB9 looked like a biennial sited in a city where power is no longer mutable; in a world, as Hannah Black writes in a review in Artforum, “dominated visually, ethically, and ontologically by capital, in which long-standing forms of struggle — the protest, the union, the political party, even critique — seem like nostalgic curiosities or reenactments, ultimately doomed to fail.”[11] In the lead-up to BB9, I was interested in a statement the curators made about arriving in Berlin at a moment when the potential for alterity it offered (especially in relation to art scenes in New York or London, for example) seemed increasingly limited. What comes after?

In an essay published in e-flux journal, artist Dena Yago characterizes a generational shift in understanding what constitutes a critical practice. “As an art student in the late aughts,” she writes, “my professors propagated the fantasy that alterity provided access to an otherwise of multinational capitalism. Armed with identities shaped when an ‘outside’ or another ‘world’ was possible, they maintained that the other is always outside, and always subversive to ‘dominant’ culture. With practices emerging in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, punk negation, slacker refusal, institutional critique, and art-as-activism were put forth as viable tactics for resistance. But to my cohort, the proposal of simple opposition over immanence did not feel appropriate or effective in resisting the conditions of our moment; it felt romantic.”[12]

IV.

Much of “Berlin 3001” is devoted to another kind of romance: that of how one feels in the city as a foreigner. This is a critical mode that has somehow proven its longevity for the peripatetic art worker and visitor of international biennials, even after the internet makes the wondrous unknowing of the flaneur increasingly difficult to come by or justify: one is overwhelmed, one is surprised, one takes note, one makes connections, one gets lost. One trusts the authority of one’s experience.

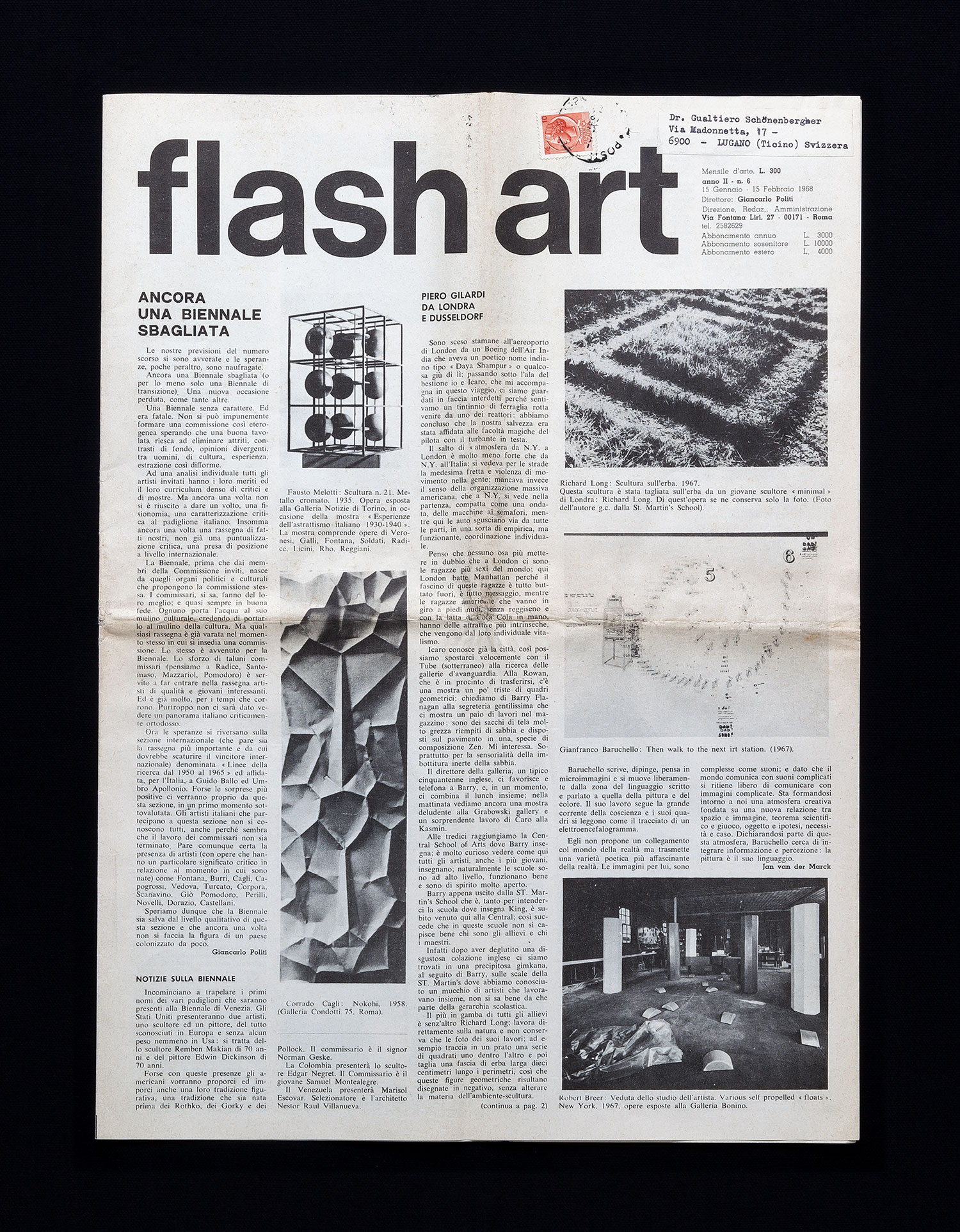

The satellite critic phoning in observations from a peripheral city to an editorial center is a model of reportage integral to the history of art publishing, and to the formative years of Flash Art in particular. What do we want from the art city? And what might a critical practice look like in spaces where the concentration of power and capital is no longer fluid?