David Elliott: How old were you when you realized that you wanted to become an artist?

Aida Makoto: At the age of ten I thought I wanted to become a cartoonist just like Tezuka Osamu, the creator of Atom Boy.

DE: Would you say that you were exceptionally talented as a child?

AM: I guess that I was more ADHD than anything else. I was an eccentric child and developed in a rather unbalanced way. I wet my bed until the second grade but was excellent at making realistic drawings and paintings.

DE: Who were your artist heroes at this time?

AM: The writers Oda Makoto and Mishima Yukio.

DE: You studied Western-style painting (yoga) rather than traditional Japanese art (nihonga) at Tokyo University of the Arts (GEDAI), and your work always seems to have been balanced between Western ways of looking and a more specifically Japanese approach. How were you exposed to these Western influences?

AM: I saw modern Western works in standard encyclopedias of world art in my middle school library. When I started making oil paintings, I was particularly impressed by Monet’s landscapes.

DE: Your work seems keenly aware of the legacies of Surrealism and Dada. How were you exposed to this? Was Mavo (Dada’s Japanese counterpart during the 1920s) an important influence?

AM: My favorite Surrealists were Dalí and Magritte. I got to know about Dada through Eurek, a Japanese magazine that was more involved with literature and philosophy than art. This young rebellious group was very attractive to me. I only knew Mavo by name. I was really a very ordinary Japanese middle-school student. I even felt rather guilty for leaving my hometown of Niigata.

DE: Do you think there are any essential differences between Western and Japanese attitudes toward making art?

AM: I guess that there must be differences, but I have no idea what they are because I do not know how a Western mind works. If what I understand as the concept of “art” in contemporary European culture is correct, I don’t totally believe in it. I think that there are probably no artists there like me — but I am not wholly sure of this.

DE: What do you not “believe” in contemporary Western European art? For me it’s very difficult to generalize about European culture and even more so when you look at the whole of the so-called West. Don’t you think that contemporary art in America, for instance, is essentially different from that in Europe?

AM: I think that after the modernization that coincided with the 18th-century European Enlightenment, Western art has contained a latent element of revolution. As you know, there was no civil revolution in Japanese history. Because of this I sense a huge gap between the West and Japan, and I feel that Western art is based on a progressive view of history that considers such events as the American War of Independence or the French Revolution as the result of certain forms of virtue. I find this difficult to understand.

DE: Did you have any deep knowledge of Western contemporary art when you were at GEDAI?

AM: Like all other art students, I got information and images from magazines. Since I had been seventeen I had kept an eye on what was happening in international contemporary art but was not particularly interested in American Abstract Expressionism or other trends. I was, however, fascinated by both performance and conceptual art, although I maintained a critical distance.

DE: What was your experience when you left Japan to take up residence in New York? Did you make any artist friends there?

AM: I am afraid that I made no long-lasting friendships with anybody there. I made some text-based, performative works such as I-DE-A, an hour long video in which I masturbated while looking at large cut-out Japanese kanji mounted on a wall spelling out the words for “beautiful girl.” I also organized a demonstration in Washington Square that protested the need to be fluent in English. I assembled my own mob and we were photographed shaking our fists while waving such revolutionary placards as “Cut Down Vowels!” “Be based on Katakana [Japanese alphabet used for spelling foreign words],” “Stop Speaking With Trilled R’s!” and “Pronunce [sic] SIMPLY and SHAPELY as JAPANESE do!!!!” This resulted from my pent up frustration after several months without any sign of my becoming fluent in English. In fact, I felt no desire to become so. I tried to observe New York carefully because it was one of the main centers for contemporary art, but I also I tried to keep a distance from it. Maybe not speaking the language helped.

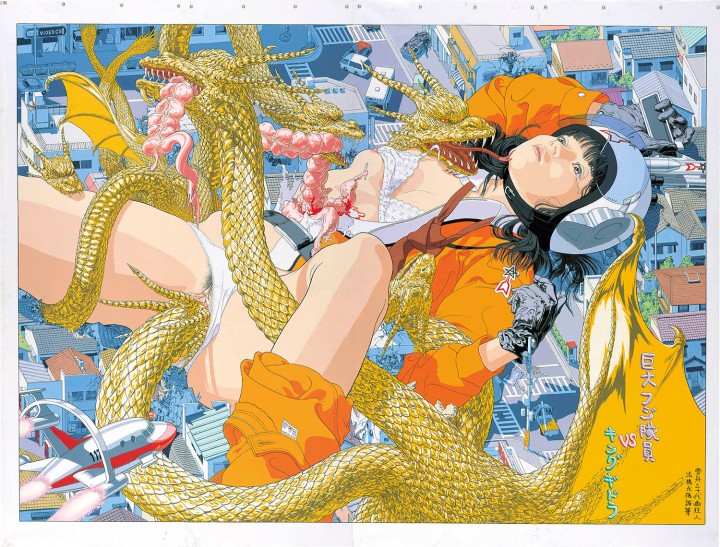

DE: Young women, often schoolgirls, appear in your paintings in bizarre, sado-masochistic poses. I am thinking particularly of the “Harakiri Schoolgirls” that have the violent dynamism of late-nineteenth-century Japanese woodblock prints or the “Moon Dog” series in which naked, amputee schoolgirls are shown with collars and leashes in a style of pseudo-traditional painting that observes different seasons. I understand these works in relation to such large works as Ash Colour Mountain (2010-11), in which millions of gray-suited salary men lie dead, slumped over their computers and desks as minute, faceless units in a misty, Chinese-style landscape painting of mountains and water. These girls are parodies of the kind of pornography that these guys consume, and I see them as a homeopathic provocation against the cult of the kawaii, the kitsch, child-like sexualization of young women. But at face value they could be regarded as promoting the very thing that they so obviously despise. Has this been a problem for you?

AM: I have occasionally been criticized because of this by women curators or middle-aged collectors who describe themselves as feminists. But this has never affected me very much because they are always so dogmatic. I guess that there must be many people who hate my work, but they don’t normally come near me so I don’t meet them. I think that being hated is one of my jobs as an artist. Regardless of any sexual issues, my work is quite distinct from my private beliefs or personality. You could say that they are in an ironical relationship with each other.

DE: Kurt Schwitters once famously said that “anything an artist spits is art.” Do you believe that anything can be art if the artist says it is?

AM: It has been at least twenty years since I decided to stop asking myself “What is art?” Whether they are regarded as art, entertainment or as just a simple event, certain things become history and others don’t. And I don’t even think that becoming a part of history is that important.

DE: You work in many different media: painting, installation, performance, video, sculpture. Is there any underlying rationale to the way you choose to work and the media you decide to use on particular projects?

AM: Every time I begin new projects I think about this afresh. Be that as it may, it seems that I am inclined to end up making paintings, which was where I started. And I am most comfortable using acrylic paint.

DE: Who are your favorite artists today? Are they Japanese?

AM: Whether someone is Japanese or not is not important. I see every living artist as a rival, so they can hardly become my favorite. I would rather use their work as a reference point from which I can steal ideas.

DE: The recent show at the Mori Art Museum was your first retrospective. How did it feel?

AM: Having to face people’s reactions, especially the negative ones, I’ve come to feel that I would like to produce something new that will win them over.

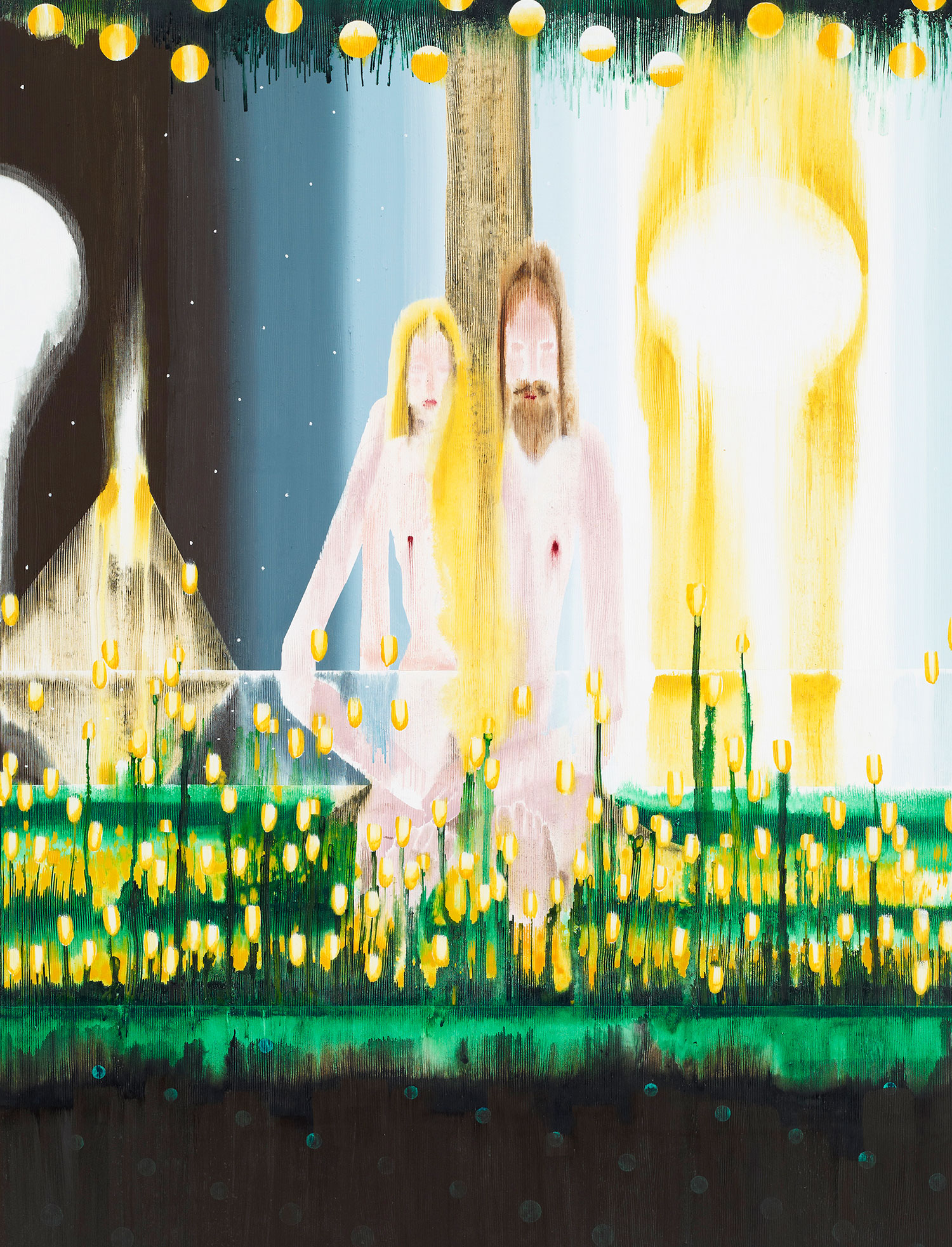

DE: The exhibition includes a number of huge new paintings such as Electric Poles, Crows and Others (three by ten meters) and Jumble of 100 Flowers (two by seventeen meters, both from 2012). Both are mega-sized versions of the screens that appear in traditional Japanese art. These works share an apocalyptic bleakness, in marked contrast to the almost baroque exaggeration of your previous large paintings. Do you think that this is a new direction in your work and, if so, is it related to the changed cultural mood of Japan after the Great Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011?

AM: I am not sure exactly whether these works will mark a new direction for me, but the earthquake and its aftermath have affected me deeply, although probably more on a subconscious level. Nonetheless, I am keeping a special lookout for any shifts in Japanese society — particularly a turn for the worse.

DE: What were the best and worst times in your life?

AM: I think it has been pretty good almost all the time. I am basically an optimist.