A certain discrepancy exists at the heart of Becky Beasley’s work. Between the dark humbleness of her sculptures and gelatin silver prints and what they are made to contain, there yawns a gulf of incommensurability. Like books, the incommensurable object par excellence, whose physical form can never even begin to convey what it contains, these works conceal more than they reveal.

Beasley likes books. Although her compulsion to collect books can’t explain the artist’s work, it can go a long way in illuminating some of its sources and concerns. Her compact, carefully crafted sculptures and photos are informed less by minimalism as seen in museums, than minimalism as seen in reproductions. As such, they often retain the compressed scale, if only figuratively, of the printed page; they seem, particularly in the photos, doubly-removed from the viewer’s space. The artist, who has also been known to make sculptures that explicitly reference the shape and form of paperbacks, such as A Storage Space (2006), a small, paperback-sized sculpture fashioned out of acacia with a sheet of black glass on the side, as if to suggest a slipcase, or Green Ream (A.G.L.A.) (2007), a book-sized container made out of black American walnut, containing 500 sheets of green U.S. letter paper, visible on one side, again, like a slipcase. In both cases, the object becomes an opaque container, concealing its contents and signifying refusal, while nevertheless intimating a vast and incommensurable interiority. The photo Gloss (II) (2007) on the other hand, could be said to grimly gesture to the absence of the book. In this brooding gelatin silver print, the artist photographs a skeletal structure reminiscent of an upright piano, which is also evocative of an empty, oddly constructed bookshelf. Something about this unyielding object seems to have expired, a feeling aided by the smoky patina of the print: not only will the object generate no more music, its will to accommodate anything (books or language) has likewise been exhausted. And yet the entrancement it exercises is anything but sterile, tending paradoxically and forcibly toward language.

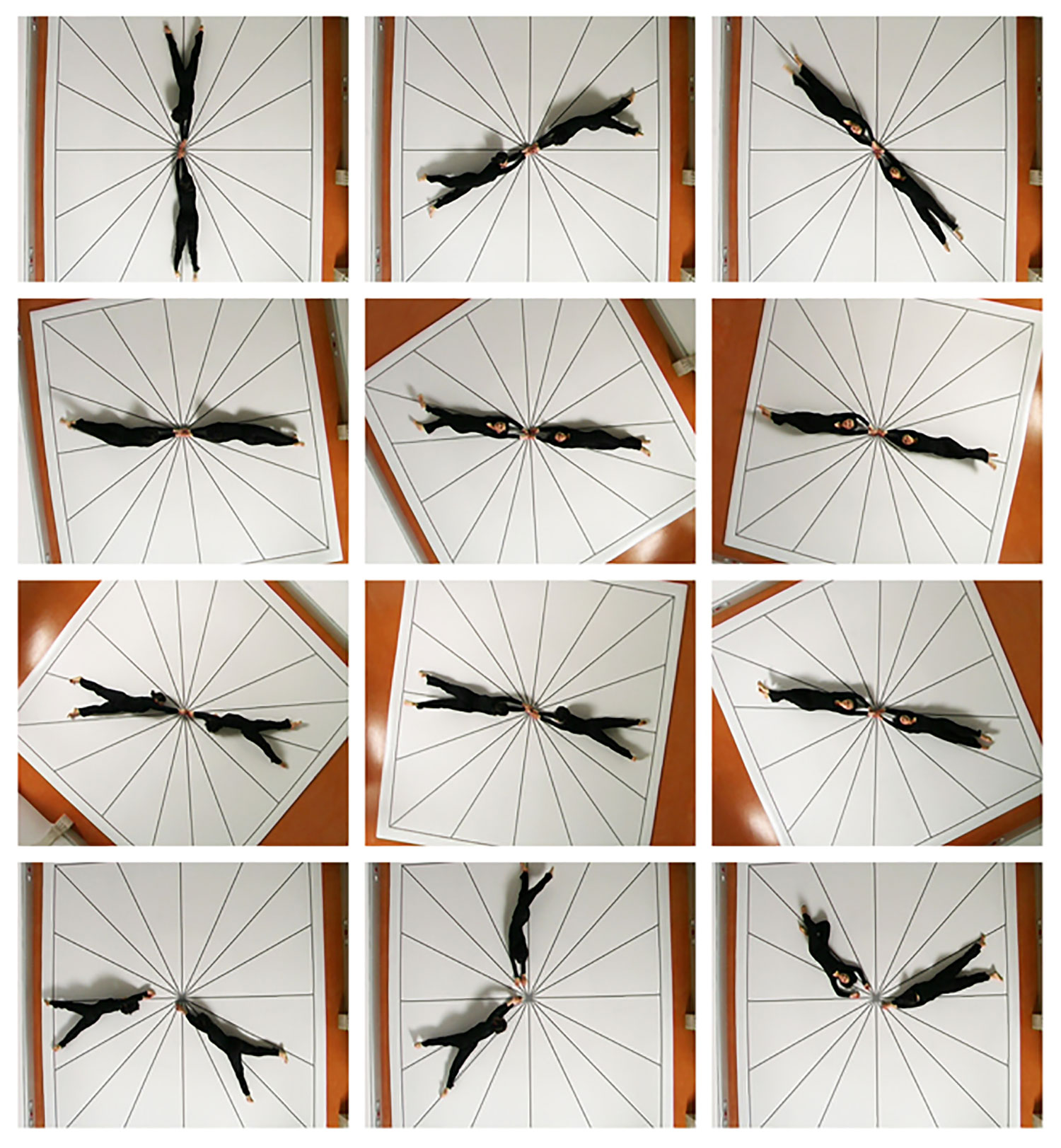

The sepulchral qualities of Beasley’s work are perhaps more evident in her recent “Plank” series. Crafted out of black American walnut veneer on paper and MDF, these human-height, quasi-rectilinear sculptures double as coffins (container) and bodies (contained). Plank (6) (2008) leans up against the wall like John McCracken sculptures, while others, like Plank (4) (Covering Ground) (2008), lay in three truncated parts on the ground. Photos of the same objects, arranged in various linear rows like syntactical units, radiate a clean, sacramental significance, as if they were invocations waiting to happen. But like Beasley’s former works, what exactly they would invoke, beyond their own mute presence, has been concealed with their unfathomable depths. In exploiting the language of minimalism, Beasley invests the somewhat antique notion of a ‘formal vocabulary’ with a new purchase and continues to elaborate her taut idiom of incommensurability.