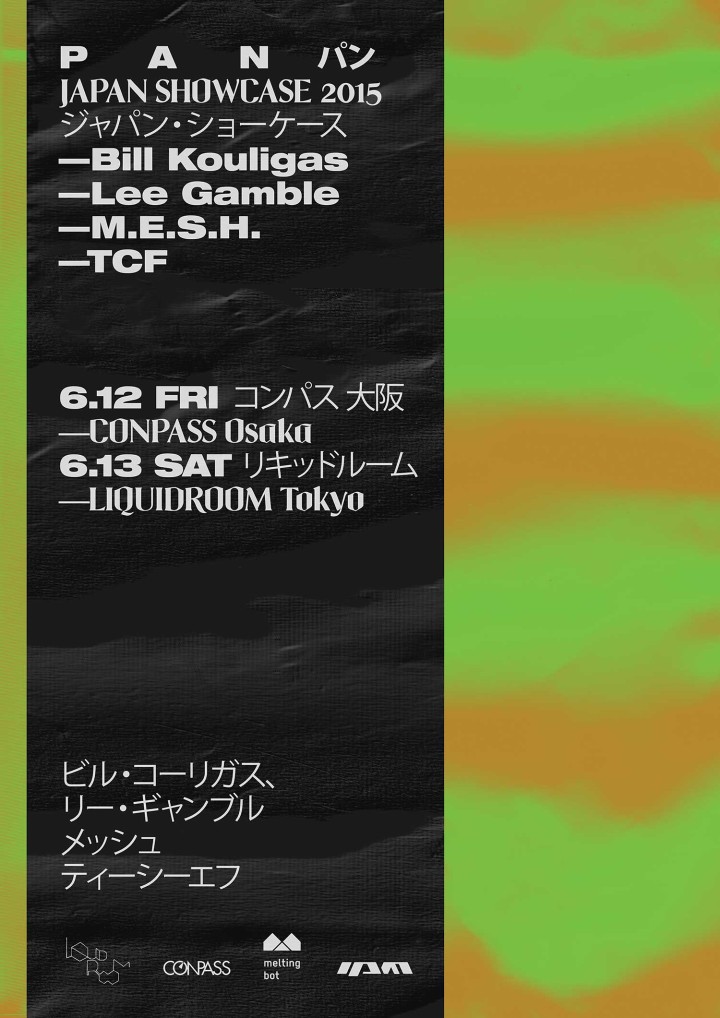

Artist Bill Kouligas runs the Berlin-based record label PAN. Kouligas grew up in Athens, then worked in London as a graphic designer before moving to Berlin, where he founded PAN in 2008. The label was created to publish music by his friends and try out, with artist Kathryn Politis, new design formats for vinyl. PAN has since developed into a platform to present and distribute work by a range of sound and visual artists spanning generations and continents. These include Florian Hecker, Ghédalia Tazartès, M.E.S.H., Catherine Christer Hennix and Lee Gamble, to name but a few. Matthew Evans met with Kouligas to discuss his upcoming projects, the role PAN plays in documenting the growing significance of music and art crossovers, and how all these unique voices interact with each other.

Artist Bill Kouligas runs the Berlin-based record label PAN. Kouligas grew up in Athens, then worked in London as a graphic designer before moving to Berlin, where he founded PAN in 2008. The label was created to publish music by his friends and try out, with artist Kathryn Politis, new design formats for vinyl. PAN has since developed into a platform to present and distribute work by a range of sound and visual artists spanning generations and continents. These include Florian Hecker, Ghédalia Tazartès, M.E.S.H., Catherine Christer Hennix and Lee Gamble, to name but a few. Matthew Evans met with Kouligas to discuss his upcoming projects, the role PAN plays in documenting the growing significance of music and art crossovers, and how all these unique voices interact with each other.

Matthew Evans: Let’s talk about the relationship between art and music.

Bill Kouligas: I’ve never actually done an interview for an art magazine before. I’ve been talking to music magazines my whole life, but it’s a different audience. But I haven’t been doing interviews with music magazines for a few years, just because it’s boring to me. To be honest, I work in music, music is my background, but what we’re doing doesn’t translate into the music world very well. I find that world very limiting somehow.

ME: How is it limited?

BK: The audience is more traditional and conservative. I hate the word conservative — I don’t want to judge or anything. Music has this element of pleasure. More than enjoyment, I see music in a creative way. The regular music fan wants to engage to have a good time, which is healthy, and that’s how it should be. But when I try to explain it, or have a dialogue with a regular music writer, it just never works. I think I sound pretentious to them, and they think I’m some arty-farty guy using their culture to suggest something else. And some people are like, just leave us alone, let music be. And maybe they’re right. Maybe I’m wrong.

ME: Do you think that people in the music industry are hesitant to embrace the art world because they believe it’s co-opting them?

BK: Yes. There’s also a solid, existing infrastructure that the music industry works with. Music generates money from a very specific flow of things, and when you suggest new things, and tweak that infrastructure, they just don’t let you. And that filters out to everything else — audience, perspectives. If you’re an art-type musician, they box you in.

ME: “All art aspires to the condition of music.” Mark Leckey says this a lot. Maybe music is in the art world for atmosphere, events, for entertainment. To assist in the sale of the objects, which is the main attraction. But we always seem to look back at music and realize how advanced it is, also in terms of economic models.

BK: It always is, because it’s a more understood culture. It relies on a real audience.

ME: Who is your audience?

BK: It keeps changing, and I think that’s healthy. The audience can’t co-opt what we’re up to, and you can’t always drag everyone along the way either. There are people who’ve been there since day one, and that makes me super happy. Because they’re also open to what you suggest, and what you put to them, and some of them end up being part of the conversation. And of course there’s always this personal journey that comes through the work, through anything that we do. We’re not jumping on every new idea that comes up. It’s more about developing as people, as artists.

ME: A lot of artists are pressured into creating more objects, and they have to become businesses.

BK: It’s the same in music, but just different numbers. It would have been so easy for me to have created a techno label. I would have been in a different place right now. I would probably own an apartment in Berlin. It’s different though, because with a techno label you build a solid audience and you come across as authentic. You always deliver what they want to hear. But I’m not here for that. Fuck your comfort zone. That’s boring. Of course there are also lots of types of music that I like, and that I listen to, but it’s not what the label stands for.

ME: But techno must influence what you do.

BK: Club culture is so dominant here that you can’t really avoid it. I like electronic music, and it’s had a strong impact on me. I took that influence and filtered it through my ideas and our practices, and we responded to it with our take on it. It’s great to see myself and my label as a vital part of Berlin. We’re part of this greater thing.

ME: Club culture here can be “monastic,” a friend of mine likes to say. But at the same time, there are artists in the city that are expanding genres. PAN seems to be a home for these artists.

BK: It’s important for me to accommodate all these types of people who can’t really participate in the really specific, genre-type labels.

ME: How do you explain the kinds of artists and musicians you work with?

BK: PAN is a network of artists who work in different fields, from different generations, different backgrounds and different types of music. Some come from academia, some from improvisation, some come through visual forms or technology. I think it’s interesting to document all these things and put them in a greater dialogue with artists who belong to a different scene. There is an element of experimentation — but I don’t like to use that term.

ME: It’s a default term, a reliable word for unreliable things.

BK: It is, because who capitalizes on that word and what does it really mean? It’s just easy and lazy. Let’s say the form is more abstract, it’s called experimental. I’m not interested in that.

ME: Do you think that people who make music get paid enough money?

BK: It depends on what kind of music you make, and it depends on the reach. A lot of club DJs get an insane amount of money, while others get nothing. I don’t think it really matters, to be honest. It’s all energy drinks and alcohol that runs this music. You can always find ways to make your living through what you do — if you’re smart enough, and are able to face reality. It’s easy to complain.

ME: You worked with Lars Holdhus (A.K.A. Aedrhlsomrs Othryutupt Lauecehrofn) on a project in which you need to buy tea in order to get the music. Forcing people to have another experience to get what they want is interesting.

BK: A lot of people have been using these sorts of ideas because most people don’t care about buying music. So I’ll sell you something else instead. I have a friend who says, “You can’t download a shirt.” And it’s true. With Lars, for example, it’s a part of his practice. Tea and music is what he does.

ME: The access you’re working with is different. It’s more of a hybrid.

BK: It’s more of a bastardized format, which is always a risk. There’s a lot of failure involved, which I like, and I’m interested in that. It’s important to know how far you can go with things. I come from a design background. In the very beginning the label worked as a platform to also express that side of things: different types of packaging and presentation than the regular record or CD. I’m currently working closely with the developer Harm van den Dorpel to build a new website that will be able to host and present all this work in multiple ways. We want it to allow artists to do more.

ME: One of the first projects with Harm is also a collaboration with Amnesia Scanner, which I’m interested in because I don’t quite understand what it is.

BK: It’s called Lexachast, and it’s a website that streams all the NSFW images from Flickr and DeviantArt to music that Amnesia Scanner and I did together. The idea was to create a visual component to present the music in a way that can’t work as art or video.

ME: What’s your background in music?

BK: I grew up in Athens, which is a pretty significant place because it belongs to Europe and it’s heavily influenced by Western culture, but it’s so removed as well, and in a way, it’s own entity.

ME: It’s also on the cusp of East and West.

BK: It’s a port. And there’s a huge influence of the Middle East and the South. It’s a hybrid itself, a weird mix of things and mentalities that sort of never made sense. All these things kept clashing, and that’s also how… It’s a big part of the crisis. People can’t really find this fine line to balance things out and work on something solid. There’s a lot of weird continuous overlap of ideas, ideologies, mentalities and backgrounds. It’s an endless war.

ME: That can’t necessarily be reconciled.

BK: Yes. So being there, experiencing this everyday, shaping your personality, you end up making your own art. That could also be how I think about the label: being your own entity, and getting all these different things from different times. Putting them in the mix and trying to make your own story out of it somehow.

ME: PAN also tries to map music that was being made in the past onto the present.

BK: I’m deeply rooted in history to be honest. To try to understand the world you have to go back in time as well. I’ve released a lot of work from the ’60s and ’70s. But also contemporaries, and I wanted to show the journey of things, how things were back then, through works that were unpublished or completely unknown. What a twenty-one-year-old kid does nowadays may be similar to something that was being done decades ago.

ME: With so much of music being catalogued online and accessible, it means music has become a low intellectual-property practice. Like fashion, or porn. You can borrow so much more easily than in industries like publishing or film.

BK: I think so. A lot of people have been complaining for years now that this free, online access is not healthy, that it kills the vibe. You wake up one morning and you have access to the entire history of music and culture. It’s fucked up. You can’t control it. You have Turkish kids in Neukölln making reggaeton, but that makes sense today.

ME: I think that out of this collage and access, you can get sounds that make us feel really uncomfortable, that are both familiar and strange. Discomfort is also interesting for music.

BK: Again, you can be creative with it. You also can’t avoid it.

ME: Maybe music allows us to reprogram. What might be abrasive today could be melodic tomorrow.

BK: That’s just modern life. It goes through everything, even politics.

ME: Yasunao Tone once said that “to fight with smart machines you have to be very primitive.” Maybe instead of trying to keep up with all the algorithms, we need to react to it in a very basic way.

BK: That’s how life started. You can’t fight with technological development. Computers are smarter than us, to be very blunt. The only thing that you can do is be a real human, which is a very primitive behavior. Be something that the machines cannot be. Be emotional.

ME: Is that what makes good pop music? Someone who can rise above all that complicated production — which is actually really crazy and experimental if you listen to it.

BK: The production means nothing though. A great pop track you can play on the guitar or sing in the shower. You can have these pompous overproduced things, but pop is always the tune, you know. That’s why it connects with so many more people. It’s more immediate. Pop is the greater form of expression. It’s the hardest one to achieve and be successful with. It’s almost impossible to make good pop music. You can be as abstract and artful as you want, experiment with media and sounds, and be all over the place. Not many people can write good pop music.

ME: Independently of PAN, you worked on an opera that has just been performed at the Volksbühne.

BK: Yeah. I worked on it with the visual artist Spiros Hadjidjanos.

ME: The guy who put the Apple keyboard inside the glass bottle?

BK: Yeah. I’ve had this idea for a very long time. I’m very influenced by the New York composer Robert Ashley, who passed away two years ago. He used the opera as a medium, but presented it in a whole new way. For example, he made an incredible series of opera plays for television. I love opera as a form, and I’m relating it to what Ashley was doing between the ’70s and the ’90s. I’d like to take it to a whole different place, a new form.

ME: Because who has time these days to sit for three hours and listen to opera?

BK: Exactly. I asked Spiros, who’s an old friend who I’ve wanted to collaborate with for a long time. He’s been doing these light installations with fiber optics. He takes these network routers, or internet modems, or whatever you call them, and he changes the whole system, the schematics. When Spiros and I were reading about the history of fiber optics, we found out that fiber optics were first used in a cultural context in the beginning of the eighteenth century in Paris at the premiere of the Faust opera. We made the curtain using these fiber optics. So the audience went into the space, and any use of a phone — a signal — translated into light. Imagine four hundred to five hundred people in the space. It just went crazy. It’s an interactive installation. Using the internet through light sculptures. He created all that scenography in the theater, based on all that. And the performers were behind this curtain.

ME: You work with space often. How much do you think about architecture?

BK: It’s vital to the experience of music. I’ve worked with Florian Hecker for a few years now. He’s been working really hard on the experience of sound. We did a show together at Berghain four years ago. We used every level of the building, from the ground floor where the coat check is all the way up to Panorama Bar. We set up a forty-eight-channel installation, and the audience could travel through these channels as they went through the space. The opera is a different dimension though. It’s for two voices. Three voices actually. Two live performers and a synthetic, computerized voice that I control. The script is by Nora Khan, who works at Rhizome. She’s a good friend of mine. We’ve wanted to work together for a long time.

ME: Although fragmented and abstract when taken out of context, the stories music tells today are very relevant. So much of music today seems to feed back to a crisis in language.

BK: That’s the whole Adorno side of it.

ME: Did you ever consider publishing literature through PAN?

BK: There is a book coming out this year. And the work I’m doing with Harm on this platform is also a way to bring people who aren’t necessarily musicians into the music world. It’s also not new. It’s been happening for decades. But it’s interesting to bring in people who work with technology, coders, and pair them with sound artists. Music doesn’t have to be the leading force. It’s our culture, and we might filter everything through elements of sound, but I hope it will create a bigger network of people not just limited to music and sound. But it also really goes back to who the audience is, and whether they’re open to all these different things.