The day-to-day reality in occupied Palestine is largely inaccessible to an international audience. It is challenging to form a deep, or even adequate, understanding of a situation that is not only physically distant and isolated but also suffers from a sort of media blockade. Mainstream media does not circulate images from Palestine or report on daily occurrences of harassment, breaking and entering, theft (of property, houses, animals, cars, and other objects), vandalism, incarceration, injury, and death. Early in their career, media artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme realized that images no longer exert the mental and emotional grip they used to have on viewers. This led them to shift their focus to sound as a primary material. Sound had always been a central motif in their work and a complement to complex images. Like many of their generation (born in the 1980s and coming of age in the ’90s and early aughts), they are profoundly influenced by electronic music and the anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist culture that grew up around raves, festivals, and other collective experiences. As the audial aspect of their work has become even more layered and complex, this musical background has become more prominent in their artwork, as seen in recent exhibitions at MoMA, Dia Art Foundation, Migros Museum, and the 12th Berlin Biennial. In the past few years, the ongoing bureaucratic “management” of the occupation of Palestine has shifted from a strategy focused on radical forms of erasure to the building of an infrastructure for constant and total surveillance.

I’d like to briefly explain the importance and extent of erasure in this colonial geography. The strategy of the militarized state is to divide and reorganize Palestinian memory in a manner that mimics physical occupation by denying Palestinians access to their own history, traditions, and even cuisine. All of this mental territory is expropriated, divided, and represented as belonging to someone else. Unlike other colonial strategies, which are calibrated for surveillance, profiling, algorithmic prediction, and data, the Israeli occupation was, until recently, the opposite. It focused instead on erasure: of official records, testimony, cultural institutions and documents, historical or archival collections, and civic society (birth certificates, passports, and other quotidian aspects of civic inclusion). Rather than controlling a society through surveillance, the strategy was to disappear artworks, film footage, photographs, books, documentation of civic rituals and ceremonies, folk dance, traditional music, festivals, and local cuisine. Access to collective and individual memory has been systematically eradicated. This is in contrast to the recently launched Operation Blue Wolf: the occupying state has shifted its focus to surveillance, profiling, and data collection for purposes of control. Due to the longstanding policy of erasure, the data currently being collected lacks crucial information and contains many gaps. As the military shifts its strategy toward data collection and surveillance it creates new records that mimic the official, administrative identities required for a functional civic society. But this new system is not only for the purpose of military domination; it also reproduces and reaffirms the absences and gaps produced by the policy of erasure. For example, the deed to a piece of property that was destroyed along with a birth certificate and a driver’s license is not reproduced under this system. Instead, the person who owned the property is officially registered as someone who, lacking this deed, never owned the property to begin with.

With this in mind, I wish to go back to the artist’s practice, which is not limited to Palestine or solely focused on the subject of physical geography. Rather, it deals in a more general manner with the mental and emotional states produced by domination. Working in performance, moving image, and installation, and with a background in sound and experimental film, the duo is committed to carving out a language that can speak to positions of forced statelessness, through the deployment of superimposition, montage, juxtaposition, and audial layering. In order to conjure the subject set adrift by colonial or other state violence, they employ sonic tropes such as stuttering and stammering, glitches, breaks and ruptures in sound and in meaning, repetitions, and vocal embodiment. In their sound practice, they use subsonic frequencies to evoke occurrences that can be felt or sensed but not heard. Their emphasis on bodily effects and residues stems from the understanding that power relations are made tangible through our audial surroundings and registered in the body. Resistance, by extension, needs to become audible in its possibilities, in its “form,” and in its sonic space.

In their practice, sound became a space for unseen or erased things to be felt and represented. The colonial relation to sound has changed the sonic landscape in terms of ownership of the voice, the instructive performance of the solitary speaker, and the performative potentialities of the resisting body. Navigating against the singular voice of an abstract military entity that coercively affects day-to-day reality demands a formal reversal of this equation. It is answered by embodiment in a non-unified, fragmented yet unbreakable, human voice. In the work Contingency (2010, four-channel sound installation, LED tickers, aluminum sheets) the artists reflect on the politics of the voice by using hidden recording devices to document the sonic landscape of Qalandia checkpoint. In this spatial work the audience is familiarized with a common version of control through the sonic domain: a single, male, monotonous, and instructive voice. Although it is the voice of a person, probably a soldier, probably inhabiting a role that distances them from their individual humanity, the voice employed is detached from humanness and calibrated to technocratic control. This is the voice that is compatible with the managerial aspects of the occupation. It is not within the scope of this paper, but Max Weber’s “iron cage of bureaucracy” might find disturbing applications in the day-to-day operations of violent, military occupations. The embodied voice offered by Abbas and Rahme is responding to these strategies. However, it is not a mere inversion. The artists’ use of embodied voice leaves room for different degrees of perceptual understanding. It is not instructive but rhythmic. It has meaning, but it is first a rhythm, a melody, a vibe. Their addressee is not a receiver but an active listener. As Sandra Noeth has suggested, by “layering, sampling, assembling, overlapping and merging materials, they translate the actual experiences at the border into aesthetic experiences.”

Similar practices are deployed in their treatment of image making: recurring sound, image, text, and other elements that provide a sense of continuity and contiguity that is routinely denied from Palestinian life experience (hence the insistence on the corporeal nature of artistic elements).

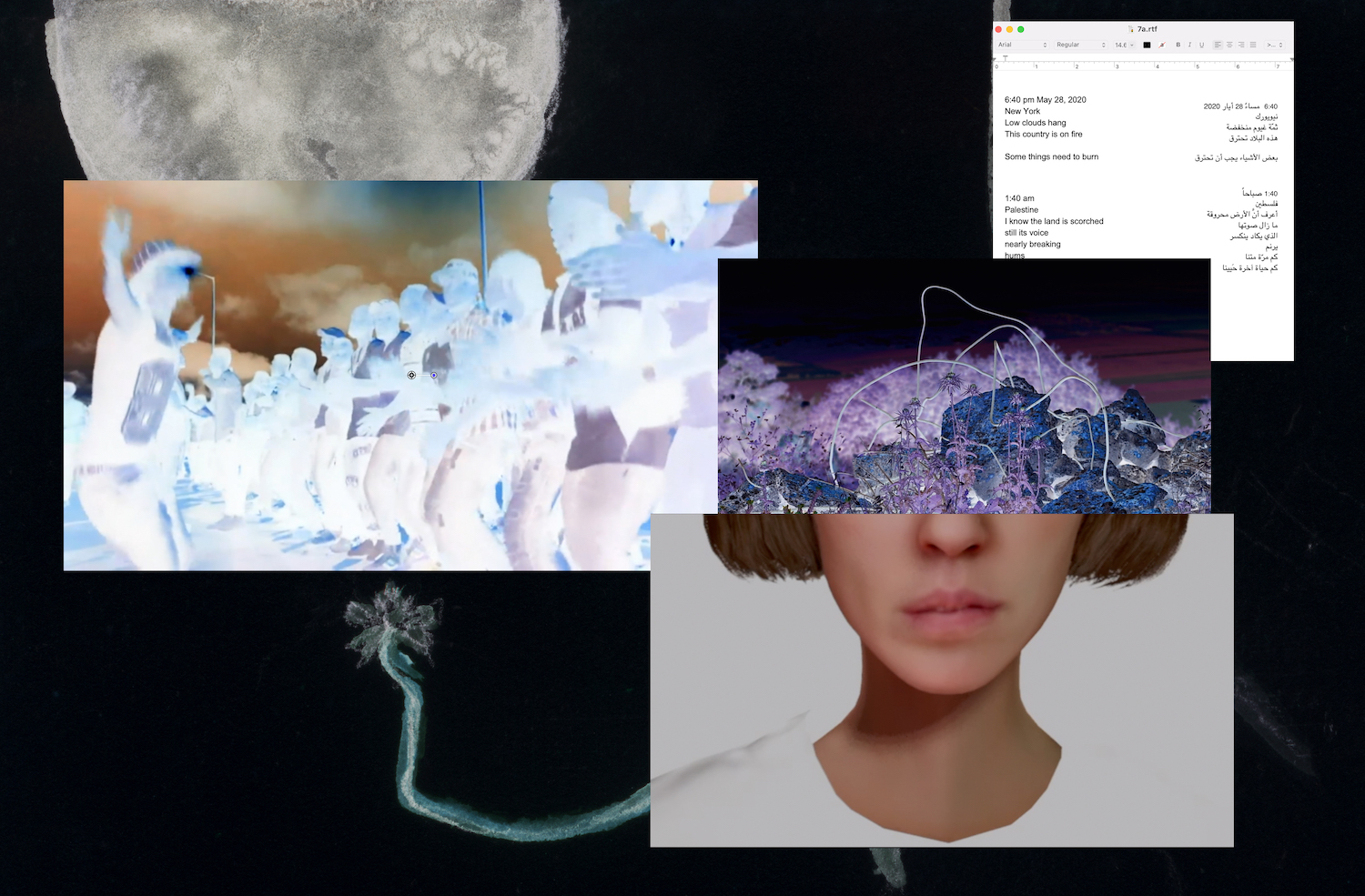

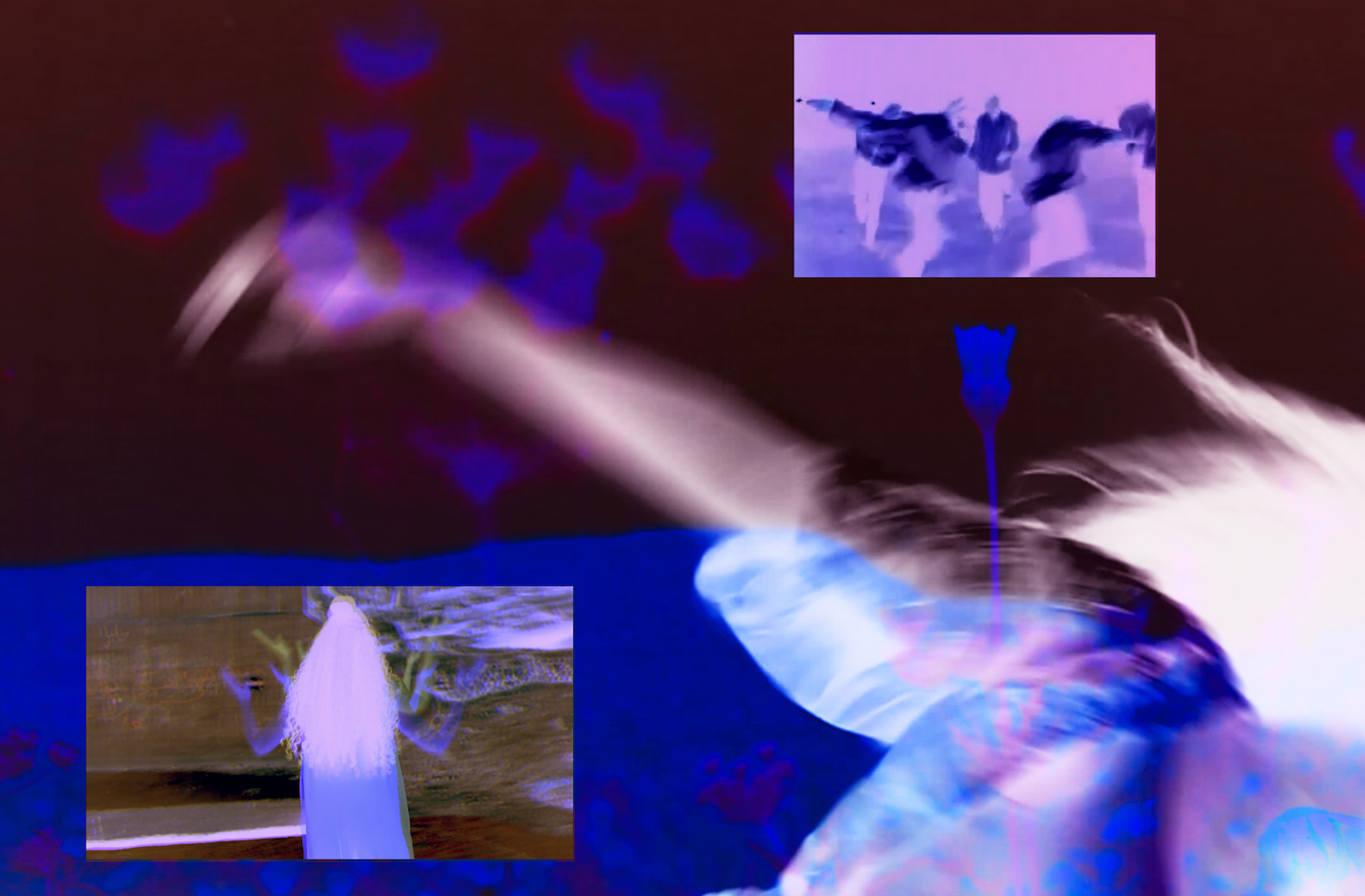

In their work from the past few years — And Yet My Mask is Powerful (2016), Oh Shining Star Testify (2016–19), At those terrifying frontiers (2019), May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth (2022–ongoing) — they use physical screens to break down the projected image’s completeness and its presented shapes, forms, and narratives, making it stutter, leak, collapse, diffuse, and surround. For example, in a recent performance and installation, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, the artists created an archive of dances, movements, physical gestures, and sounds. This archive is a growing corpus of witnesses that testify in order to produce an account of culture, history, and experience as a supplement to the records lost through orchestrated erasure. It functions as an attempt to heal and restore, listen to and visualize the diverse forms of communion and the rich social and civic lives that have been lost. It is an online, open collection that allows people to share, upload, and expand on already existing files. Unlike an archive, which implies authority and even a legacy of imperial recordkeeping, this corpus suggests plasticity and is connected to the body and ideas of embodiment that contradict the archival mandate. This corpus is reforming its relation to erasure and memory by inserting the body into an apparatus for memory making and entering extra-linguistic forms of expression into the record. The organization of the archive reflects a relationship to history and cultural recordkeeping that is far from objective or systematic. As Frantz Fanon observed, objectivity always works against the colonized subject. Similar ideas that leave room for embodiment and bodily presence pervade their projected image work. The artists overlay screens in front of a projected image, to diffract a single image and its uniform reception, creating layers, covering parts, sampling others, reveling in incoherence, layers of meaning, and the falsity of a single “objective gaze.” Navigating the occupation, the artists sometimes have to film under dangerous conditions, never knowing if they or their collaborators will be arrested or if their footage will be confiscated. All of this has happened at various points when producing works under such vulnerable conditions. Sometimes footage is taken from CCTV cameras, appropriated from online images, or borrowed from archives shared with the artists. Such imagery can emphasize specific characteristics of precarity by means of acceleration or slowing down, elusive angles, and the use of harsh montage. Responding to a saturated media regime that excels in political silencing, the sense of sight has been exhausted, but the body dedicates a different kind of attention to sound. Its operation is not limited to our ears but extends to our psyche, emotion, and memory. Frequencies that cannot be censored or silenced form an undercurrent to the forces of control and the ways that they weaponize reason, science, logic, objectivity, and rationality. Those “tactics” of presentation can be seen in most of the components of the work: sound, image, installation, etc. But these fugitive means operate in the artists’ nontraditional use of subtitles and text as well. The artists use a fair amount of poetic text in their work. Sometimes the text delivers the spoken word that was sampled or spoken in a non-English language, and often the texts are a combination of short, performative, textual gestures that the artists write or borrow.

The text is not layered onto the image in a place the eye is accustomed to reading subtitles. Rather, the text visually plays with and negotiates its “place” and how it informs the image. A certain degree of hierarchy is embedded in the role of subtitles. They operate like traffic signs — telling the viewer how to move through the space of the image. The artists use this to “lead” the eye toward a certain degree of fugitivity. As it chases after the text, the eye becomes adaptive, agile, guided by non-rational, non-traditional forms of access to meaning. The eye has to adapt to the performative strategies of the text. This way of working betrays the superiority of the image/text and favors retinal resilience: visual comprehension is here bound up with an ability to survive. And the very ability to organize the components of life under military occupation into some comprehensible and temporarily navigable form is an important way for subjects to assert agency. Whereas merely living can be a reason for erasure, erasure also functions as a proof of existence. A vicious cycle of erasure is created at the point where the feedback loop is fed the cancellation of identity, heritage, trade, ownership, memory, culture, rights to movement, health, and well-being. Against this militarily constructed void the artists offer a form of resistance that addresses the erasure itself. This “mechanism” is translated in their work into a living corpus that calls for a reassessment of the dichotomy of presence and absence.