The reactionary, provocative, post-ironic It girl has emerged as the most influential figure on the New York art scene. Is she the new face of the avantgarde?

The woman who is contrarian and provocative, who will transgress social taboos and have fun trolling online moralists; the woman who cloaks herself in post-irony, wears an impish smile, and shares her mischievous life with thousands of followers; this kind of woman has become the most influential figure on the New York art scene.

The femtroll, or the Based It Girl, is a mysterious figure, a contemporary trickster. And like all tricksters, she has arrived at a cultural crossroads. In ancient Greece, travelers placed stones on cairns at crossroads in honor of the trickster Hermes. In the Norse mythos, the trickster arrives at a crossroads in time. Loki’s trolling of the gods increases in severity until his mischief causes Ragnarök, the end of the old social order and, in the final stanza of the Völuspá, the beginning of a new age.

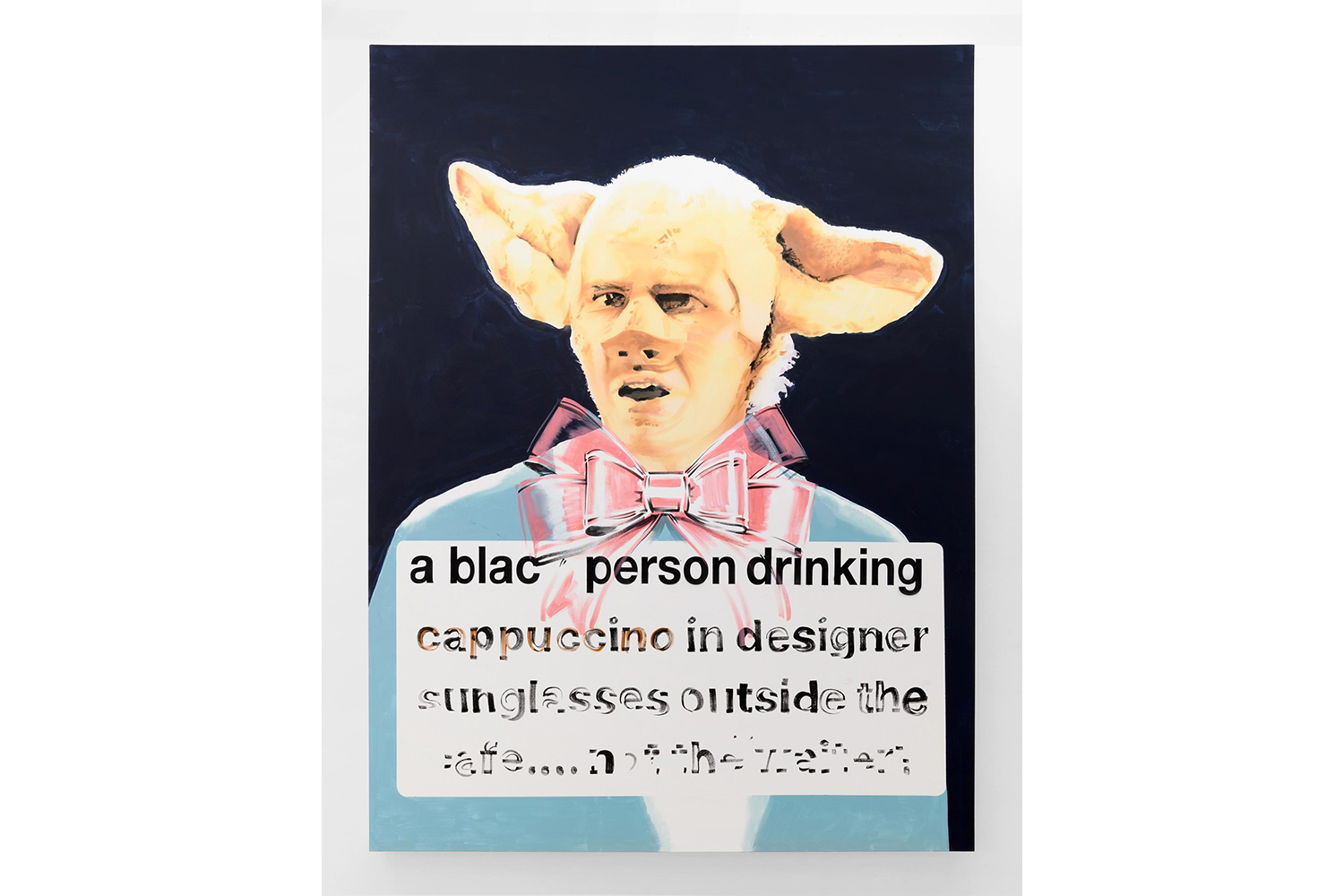

It makes sense it’s time for a backlash, a new era, a fresh cultural face. During the Trump years, American culture lived through a moral panic. For seven years, the art scene reacted against police killings, creepy men, and structural inequality. But this is no longer a country led by an autocratic billionaire. This is no longer a city seething with racial protest. When I heard the first rumors of the femtroll, it was September 2021 and the crypto market was hot, and because I needed a drink after a pandemic behind my desk, I decided to go downtown to see her for myself.

Downtown was where the Based It Girls were gathering. Downtown, where Essex meets Canal, was where the femtrolls were hanging out, saying “no thoughts, just vibes.” I am on my way to Canal Street when I come across the artist Jamian Juliano-Villani. “I’m so sick of art,” she says. “Everything is so fucking boring. I can’t remember the last time I saw something cool.”

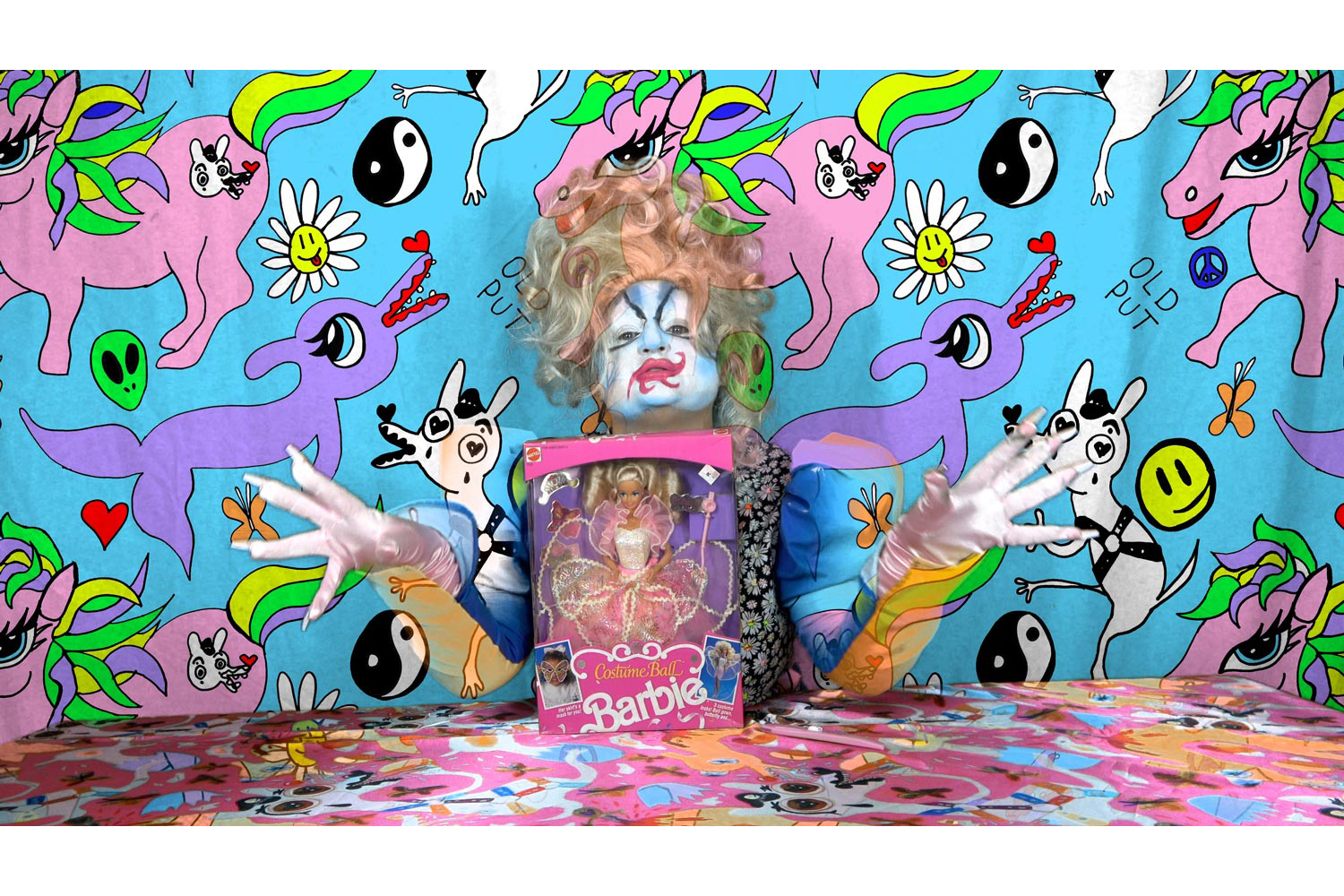

So, she has decided to open a gallery. To make something cool. She gives me a tour of the space she has named O’Flaherty’s. She also shows me a remake of an Allen Jones sculpture: a black female mannequin in S/M gear, lying on her back, her body functioning like an armchair. I ask Jamian if that’s a good idea — a black female figure as a piece of furniture. Isn’t that, a little, problematic?

“I hope they cancel us,” Jamian says. “I mean, it’s just dumbness. Taste is out of the door.”

A few weeks later, I see Jamian talking to a police officer in front of O’Flaherty’s. So many people have showed up to the opening that the neighbors are complaining. Inside, guests take selfies with the mannequin. No one is calling for a boycott of O’Flaherty’s. No one is cancelling Jamian online. “We’ve got strippers at the after- party,” she says.

It’s early spring and someone says that if I want to meet some femtrolls I should go see a new play in a Pulitzer Prize–winning writer’s loft. In the first act, an actress lifts her cocktail glass. “I like my men like I like my martinis. Ice cold and extra dirty.” After the performance, an art critic is sitting on the floor with Hannah, a young writer in cowboy boots. They are talking about Dasha Nekrasova, the podcaster.

“Dasha is Catholic now,” the art critic says. “But she also says the pope is fake.”

“Everyone’s a Catholic now,” Hannah says. “It’s, like, a meme. I don’t think they really go to church.”

People downtown are always talking about Dasha Nekrasova and Anna Khachiyan, the two hosts of the Red Scare podcast. Before the pandemic, Dasha and Anna were best known as a part of the Dirt Bag Left, a group of socialist-leaning podcasters supporting the campaign of Bernie Sanders. Now they are the unofficial leaders of the based downtown scene. On the platforms, Anna declares: “I wish I could writhe around in bed all day wearing some slutty getup a man bought me, but instead I have to be an ideological freedom fighter because no one else will do it.”

Anna and Dasha see it as their mission to troll the hypocrites of late capitalism. Among their favorite targets are online social justice activists, Ella Emhoff, and neoliberal girlboss feminists. Between them, Anna and Dasha have three hundred thousand followers. Most of them seem be young, frustrated, primarily white men. But there are plenty of women, too.

“Sorry, but airing out alleged sexual predators in a literal Twitter thread isn’t ‘seeking justice’ or ‘telling your story,’” Anna declares online. “It’s attempting to capitalize on your trauma in exchange for agreeing to be exploited by a massive digital platform.”

On the podcast, Anna and Dasha call themselves “retarded” and speak with a world-weary sleeping-pill drawl, as if they are chronically disappointed. Their technique is to cloak their provocations in a fog of deadpan irony. Example: “I want to move to LA and give up my misguided intellectual aspirations to be a retarded yoga pants juice slut.”

Hannah tells me about the trad cath founders of the art magazine Forever. Anika Levy and Madeline Cash wear lacy dresses and cross necklaces, claim to pray the rosary, and talk about “rejecting modernism, embracing tradition.” I’m more interested in Anna and Dasha’s trolling. It’s fascinating to watch grown women act like teenage trolls on 4chan. My entire life, the cultural vanguard has marched toward the identitarian left. And now it’s radical to be an edgelord? I ask Hannah if Anna Khachiyan really sees herself as an ideological freedom fighter.

“No one really knows,” Hannah says. “That’s why they call it meta- irony.”

On my way home I see a crop top in the window of a clothing store. Over the chest red and blue letters read: CANCELLED ADJACENT.

***

It’s a summer night and we’re getting a drink downtown. Young women wearing satin dresses are ordering dirty martinis, and it seems like a sign. A dirty martini is not about being pure and natural, like the sulfite-free orange wines the tote- baggers are drinking out in Brooklyn. A dirty martini is chilled alcohol and olive juice — it’s about looking decadent and getting wasted fast.

James, a young artist, tells me about the writer Honor Levy. Honor is Jewish and twenty-five and a convert to Catholicism. On her account @abuser0_o, there’s a photo of Honor wearing a pink bikini: “My family has financed both sides of every war since Napoleon #JewishPrivilege.”

“Whoa, Honor Levy is based?” someone writes in the thread.

There are many definitions of what it means to be based. “It’s, like, an attitude,” Hannah tells me. “It’s, like, the opposite of cringe.” Originally referring to a dopehead, someone on crack cocaine, the word is said to have acquired its current positive connotations from the rapper Lil B: “Based means being yourself, not being scared of what people think about you.”

Hannah tells me about the art-world publicist Kaitlin Phillips. During the pandemic Kaitlin became notorious for flouting COVID-etiquette, sharing photos from maskless parties in her apartment, much to the outrage of tote-bag moralists on the platforms. Now she is being interviewed by the New York Times. “So Kaitlin told a friend that she hopes the Times will portray her as fascist-adjacent,” Hannah says, laughing. “Fascist-adjacent!”

Femtrolls like Jamian and Anna and Dasha and Honor and Kaitlin function like a social safety valve. Every time they transgress a taboo online, they let out a little steam from the simmering frustrations of young white men. The femtroll releases repressed male anxiety through safe and nonviolent means, but she also speaks directly to young women like Hannah, who admire the courage of artists like Jamian. Young women who have seen how speaking your mind can cost you your social status and your career, and who roll their eyes at what they see as a sanctimonious, didactic, and hypocritical cultural elite running the museums and publishing houses of New York. I ask Hannah if she is amused by the stupidity of life online.

“That’s a nice way of putting it. I think we’re all really frustrated.”

The femtrolls and Based It Girls I meet downtown are all angry at the erosion of the American middle class. They are frustrated with the corrupt plutocracy and a corporate media that is distracting us with vapid cultural wars. The femtroll wants real material change — not diverse Disney characters and rainbow flags on Wall Street. The femtroll knows she is not being represented by a diverse figurehead at the helm of the neoliberal ship of death. She is being marketed to.

“I just want people to have free health care, honey,” Dasha Nekrasova says.

“I’m not, like, into politics,” Honor Levy says. “I just want to have a family someday.”

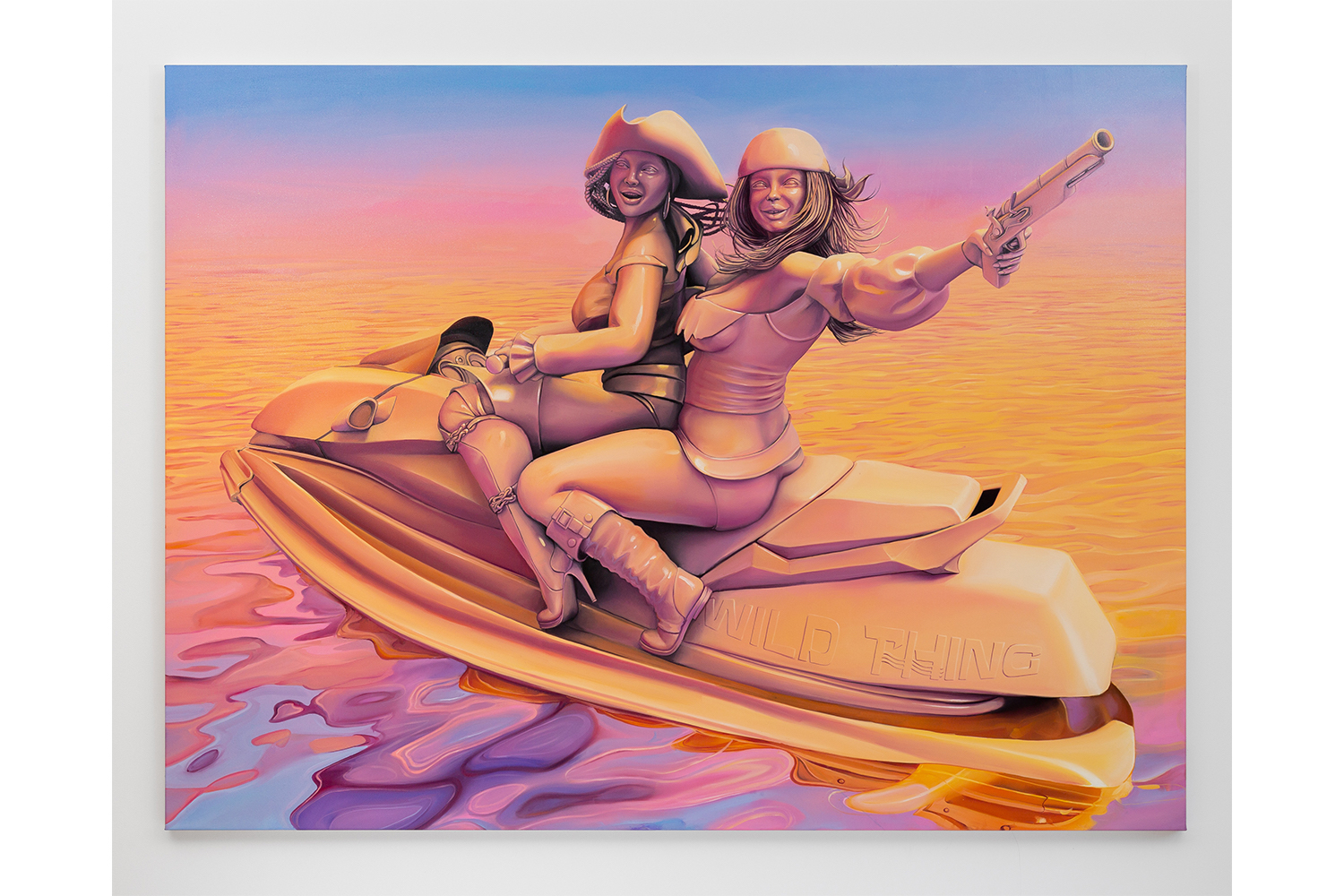

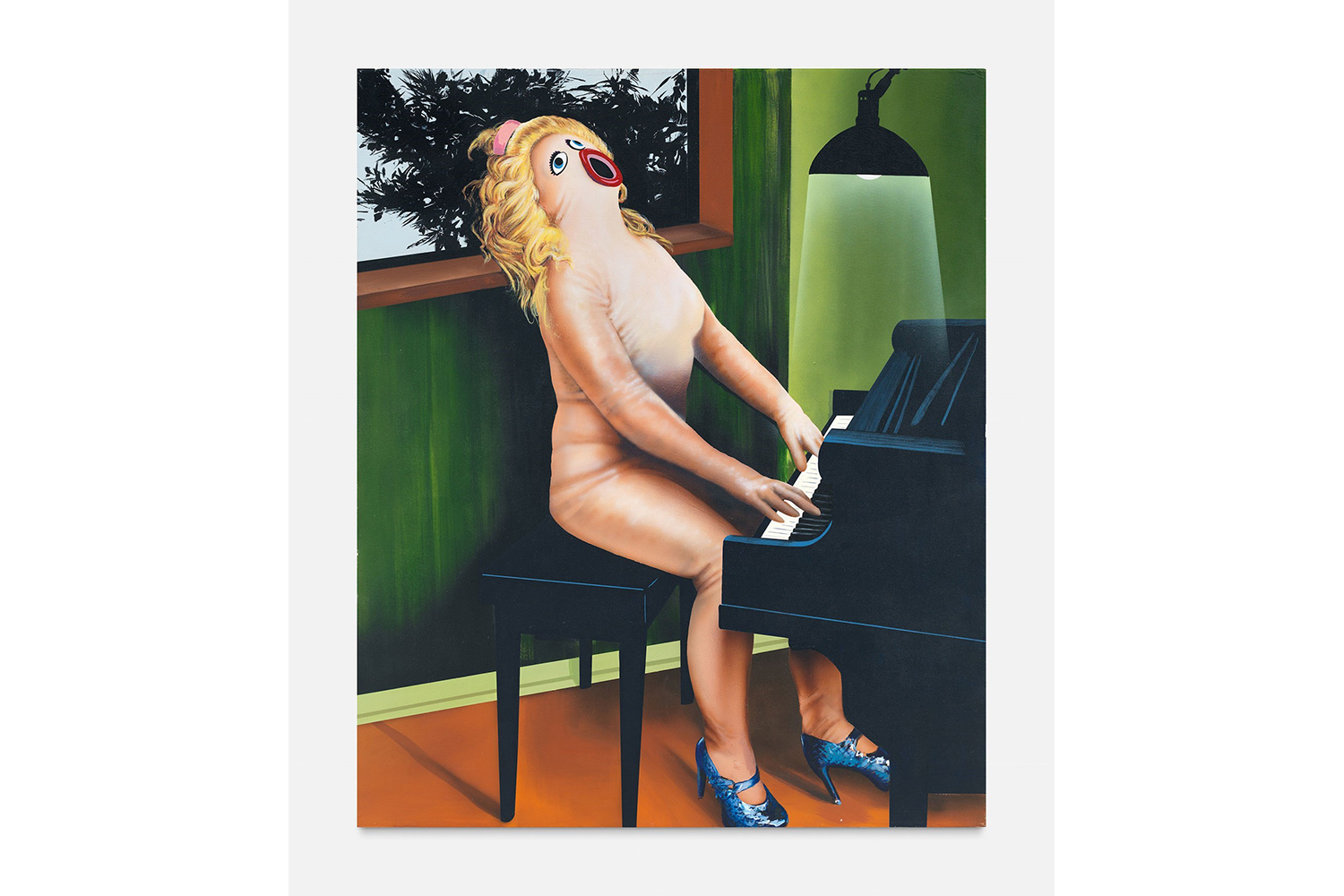

With her online excesses and trad cath pageantry, the femtroll belongs to the decadent tradition. Everything she does is vulgar, distasteful, morally debauched, like the dandies of the fin de siècle. Joris-Karl Huysmans, Oscar Wilde, and Joséphin Péladan, who, like the Based It Girls of downtown New York, turned their backs on what they saw as a degenerate society and fled into artifice and religious fantasy.

Like the decadent dandy before her, the femtroll is reacting to the wave of middle-class hypocrisy that always crests in the wake of a great moral panic. In the 1880s, the decadent dandy reacted against the sexual hypocrisies of the late-Victorian moral panic.

In the 1960s, the hippie reacted against the stifling conformity of the lavender scare and the hypocrisy of McCarthyism. The femtroll is reacting against the cancellation of museum shows, the public shaming of artists’ sexual mores, the online policing of microaggressions, all that the bourgeoisie virtue signaling — in short, against the moral panic of the Trump years.

The next day I drop by @abuser0_o and watch Honor Levy hold her eyes on a plate. Under her eyebrows are two black holes, and as she rants to her followers, her eyes flick from side to side on the plate.

“I’m like, what? A reading? How very, very gay. Not to be a boomer about this, but a reading — what is that, besides just pure dopamine and saying words at each other. Guys, we have social media. Now you’re just replicating social media in real life.”

She leans forward, her face filter glitches, and her eyes return to her head. When I see Honor Levy garble streams of consciousness behind elaborate digital skins, I see a femtroll approaching a kind of mysticism. A foolish mysticism, of course, but foolishness is an ancient spiritual tradition. The oracle at Delphi mumbling high on fumes. The Norse vølve singing with a wild and mindless enthusiasm, until she falls into a trance. In her most adderalled moments, the femtroll reminds me of the Orthodox jurodivost, the Fool for Christ who rants incoherent gibberish, breaks out in random song, and flouts society’s conventions to reach the divine. In early Christianity, voluntary foolishness was related to the rejection of hypocrisy, a rejection of society’s brutal quest for power. But the femtroll does not only play dumb for God — it’s her survival strategy, a smokescreen to confuse vindictive online activists. By shrouding her political statements in a haze of foolishness, the femtroll can pretend it’s all a joke, that nothing is serious, not even her own discontent. But underneath the foolish attitude, she hides a blackpilled heart.

***

We’re having a drink at an artist’s apartment downtown. A magazine editor says he has promised to send Honor Levy a writing prompt. Do we have any ideas? “A writing prompt?” a young writer says. “That sounds gay.” At first, whenever I heard someone say gay or retarded or slut, I thought of an edgy teenager rebelling against her millennial tote-bag mom. But back then I was only just beginning to understand the radical potential of the femtroll.

Of course, the edgelords and internet trolls on 4chan had always understood it. The Republican political strategists were beginning to grasp it, but the cloud of post-irony that hung around the downtown femtroll made her difficult to unpack for the mainstream press. The journalists seemed confused, and covered the “vibe shift on Dimes Square” as a fashion phenomenon, or an aesthetic pose, or an art-crowd inside joke, or an elaborate PR trick controlled by Peter Thiel. But the online activists on the alt-right understood perfectly well what confounded the media — we were witnessing the emergence of an important new cultural figure, a female role model unlike anything we’ve seen before. We were witnessing a group of grown women so down on American hypocrisy they said, YOLO, fuck my life. If we can’t be free, at least we can be based.

This was not your traditional teenage rebel without a cause. The femtrolls were mostly in their thirties, and there wasn’t much shared conformity left to rebel against. At some point during the 2010s, our institutions lost their grip on our shared reality. Maybe they had told us too many lies. Maybe the elites had dodged too many taxes, hoarded their profits too hard. Maybe we simply had too many screens around to distort our shared reality, like a fun house mirror maze on a planetary scale. These were women who had grown up in a world reenchanted by the internet, and their reality was shaped more by memes and algorithms and rumors in the DMs than by books and journalism and dinner-table conversations. These are women living less in downtown New York than on their feeds — now you’re just replicating social media in real life — and they are filled with a blackpilled hopelessness, a deep conviction they are living in a sick culture that is not worth fighting for.

These are the new femtrolls, and they do not want to be pure and clean and virtuous. They want to have fun while the old world is dying.