On first receiving the commission to write a profile on Barbara Kruger, my mind flashed to her piece Untitled (Your body is a battleground), a work that I was feeling particular resonance with at that moment as I picked away at scabs left from ingrown hairs on my thighs — a result of having to feel presentable on the beach and one of the more minor expectations placed upon me as a person living in a female- identifying body. My throbbing scabs will heal, but the pain that Kruger’s 1989 artwork addressed is less trivial. It’s the pain of an outsider’s power influencing a life and a body, a pain that resonates with so many women universally, and a paradigm that Kruger has worked relentlessly to shift over decades of image making. I’m somewhat obsessed with words and women, so Kruger orbits my creative galaxy consistently, and the power of her text-on-image artwork has become etched in my mind.

I first encountered Kruger in high school at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. “Know nothing, Believe anything, Forget everything,” the work declared. Straight to Instagram that would go. I knew I recognized the white text on the red banner, but I couldn’t place it at the time. I was yet to learn that this particular Futura Oblique typeface, a symbol of modernity and hope in post-WWII America, was inspired by the constructivist artist Alexander Rodchenko and was simultaneously plastered across millions of skateboards made by the streetwear brand Supreme. There was a familiarity about it that sat well with me. A sense of reassurance came with the recognition. In hindsight, I considered myself a bit of a punk and rebel, and I knew Kruger’s anti-capitalist messaging was “on brand.” I recognize the irony of this now.

It so happens that it’s Kruger’s seventy-ninth birthday on the day I hand in this piece to the editor at Flash Art. It also happens that I’m no longer in high school and, having spent five years studying journalism and a further four running a literary magazine, WORMS, my love for Kruger (and words) has grown beyond thinking that her text-based collages are merely “on-brand” and Instagrammable. My adolescent, overstimulated, capitalist-conditioned mind had done precisely what Kruger had been critiquing — it had commodified this graphic work, keeping me afloat on the surface of this visual experience. As I began to understand the deeper layers of creative expression in my post-teen years, as my body changed and I learned the malleability of words, I came to appreciate Kruger for the crucial role she played in awakening women, like me, to the power of advertising, branding, and, most importantly, to the need to question all language. To read between the lines to receive tone, sarcasm, interrogation, and affirmation. To not settle for a single line of text. To sit with words, to feel them out and sense their meaning through the body. To come back to certain phrases, to see how experience changes perception, and, critically, to take time with it all.

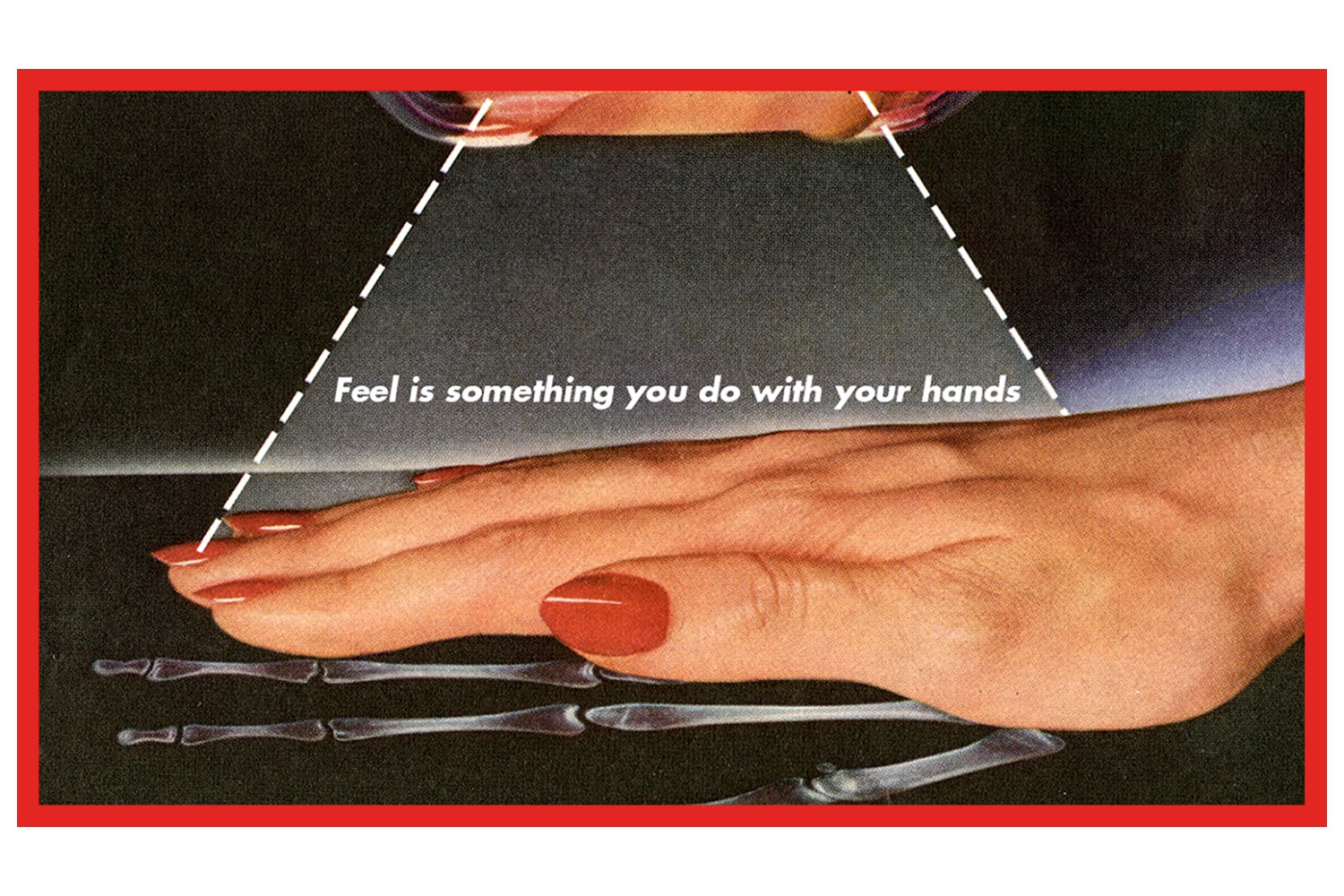

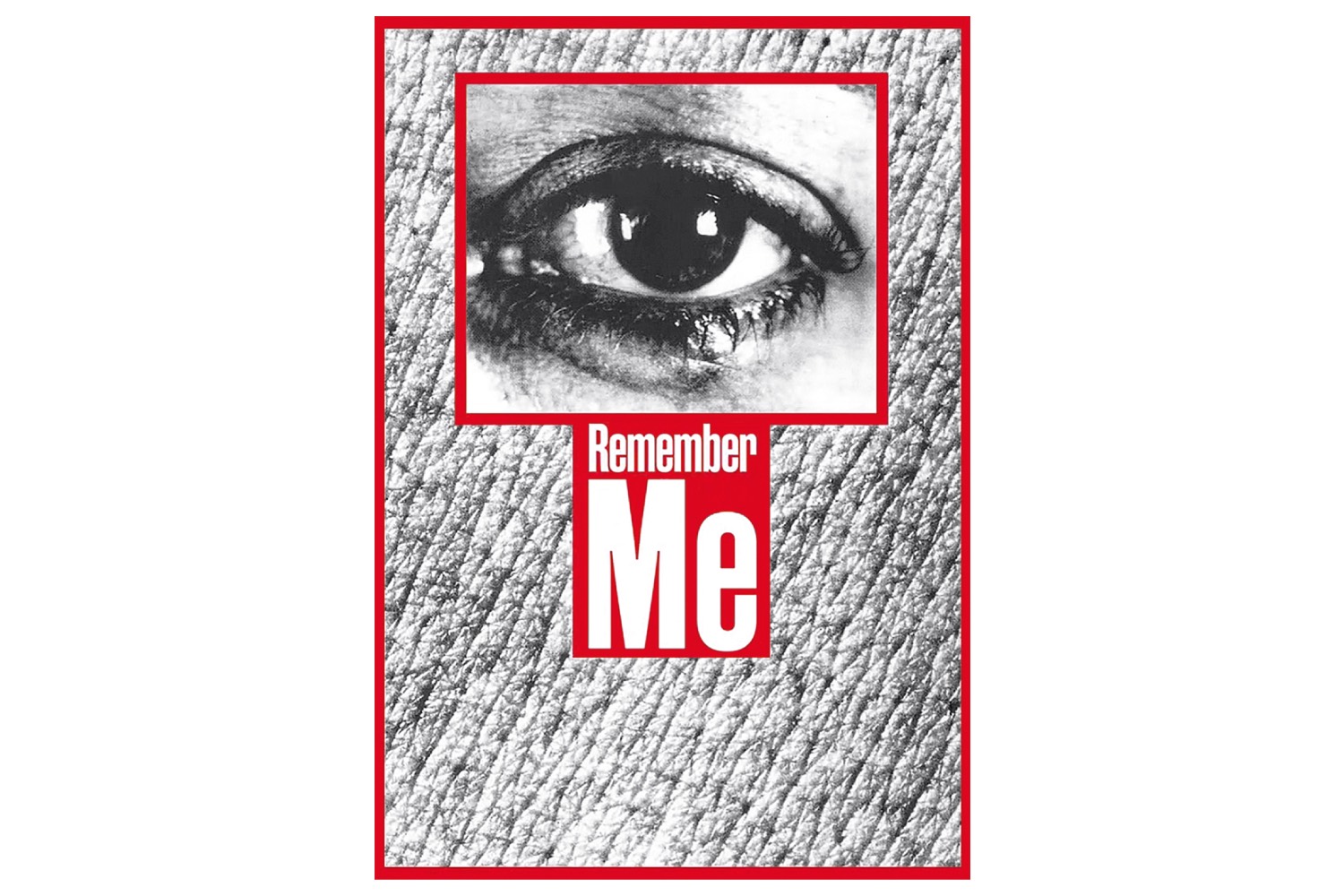

Abandoning her creative studies at Parsons in the mid-1960s, Kruger refined her style and taste by working in magazine publishing at Conde Nast as a graphic designer. In the 1970s, the young artist would go back to making art, and in 1976, after a brief stint of teaching at the University of California in Berkeley, she inaugurated her signature text-on-image collage style. From her days creating graphics, she learned the skills that would develop into her vast body of work. By pairing mundane images of the quotidian with textual aphorisms, she discovered she could force the viewer to question the motives behind their everyday visual bombardment. Using images found in magazines, she cultivated that “familiar” feeling I had as a culture-hungry teen. Unashamedly, I still feel comfort in the familiar, and Kruger is the first to declare that denying comfort in popular depictions is “sadly deluded.”

Words are particularly interesting to me because of their inherently underrated abstract nature. We’ve all learned that words can change shape entirely when taken out of context. What’s more, implications change, and, while a word may maintain its formal definition, politics, popular culture, protest, and time can shape the meaning behind the meaning. Words are never set in stone. They change with us. We change our associations, grow our vocabulary, and experience our lives through the lens of language, but there’s always room for movement. Kruger is a great utilizer of this malleability. Despite addressing themes of women’s bodies, class, capital, complex power structures, consumerism, and advertising, she dismisses the idea of being a “political artist.” Unlike a political artist, her work is “seldom incident- or event-specific but tries to create a commentary about the ways that cultures construct and contain us,” she told The Guardian in 2022. She reminds me of the poet Audre Lorde, who asserted that writing is a tool for fighting and surviving, and poetry a medium of resistance. I feel echoes of Kruger in Lorde’s poem “A Litany for Survival” (1978), in particular the lines, “for by this weapon / this illusion of some safety to be found / the heavy-footed hoped to silence us.” Here Lorde refers to fear as a weapon; her shield is poetry. Kruger’s work responds to the weaponry of power; her shield is art. Although the writing that is most frequently quoted in her work hails from the likes of M. de Voltaire, Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, René Descartes, and even the US Pledge of Allegiance, when they come through Kruger’s visual medium, the fungibility of language is truly recognized.

In this vein, the previously mentioned Untitled (Your body is a battleground) materialized as a placard for a 1989 women’s rights march protesting anti-abortion legislation that had just been passed in Washington. The one-half-inverted image of a female model’s face is split in two, representing the clear-cut division in the voting outcome. That same year, Monika Sprüth of Sprüth Magers Gallery dedicated a page of her publication Eau de Cologne to the artwork, and also wallpapered her booth at the Art Cologne art fair with it. Kruger credits Sprüth for the popularity that she gained in Europe thereafter. In the years since, the piece has become a battle cry for women across generations. Its message, having survived more than a quarter of a century, is imprinted in the minds of young women, offering solidarity, care, and comfort in its resonance. As men in positions of power continue to take over women’s control of their bodies, Untitled (Your body is a battleground) becomes a treatise for survival in its own right, an objectification of the reality of being alive today.

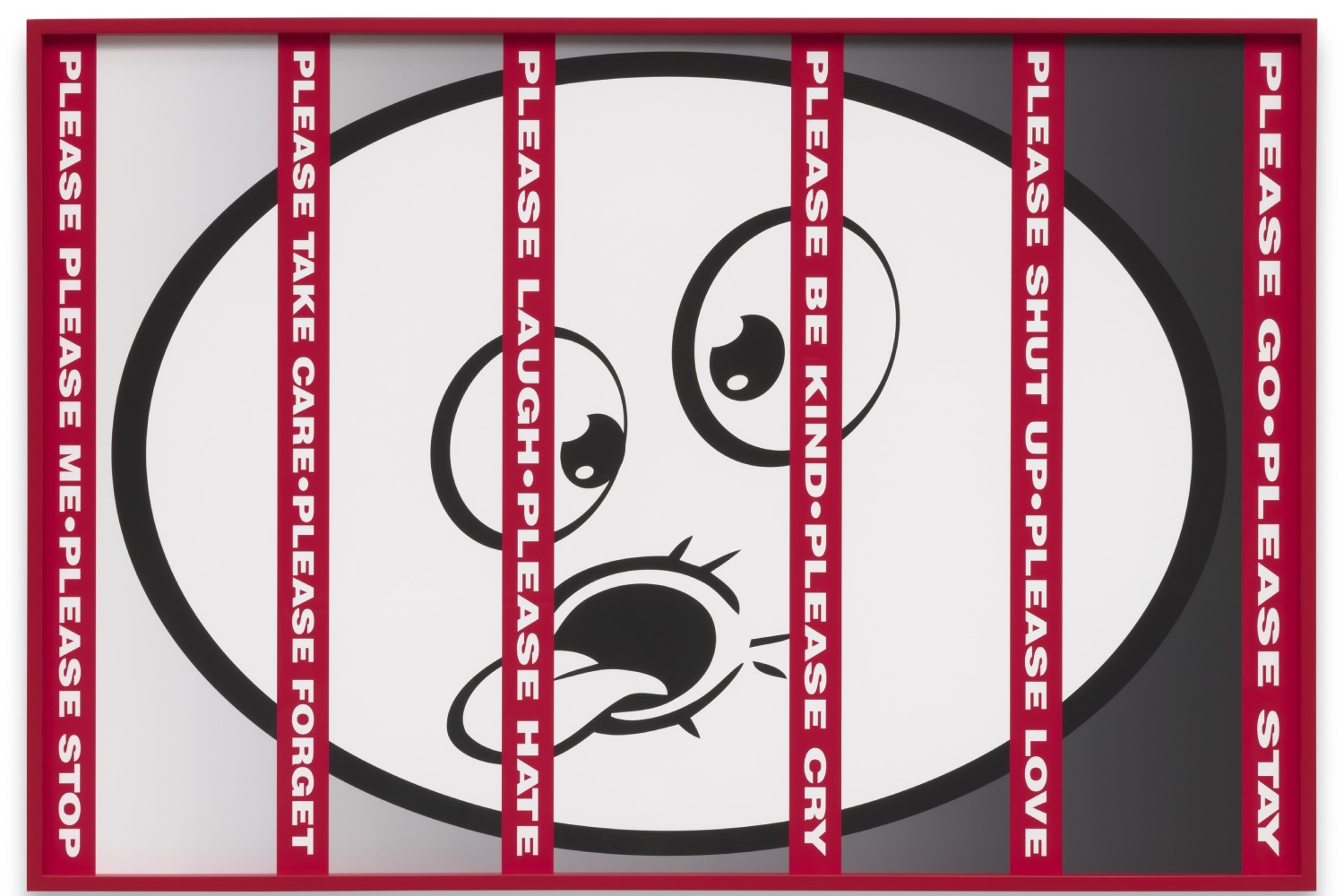

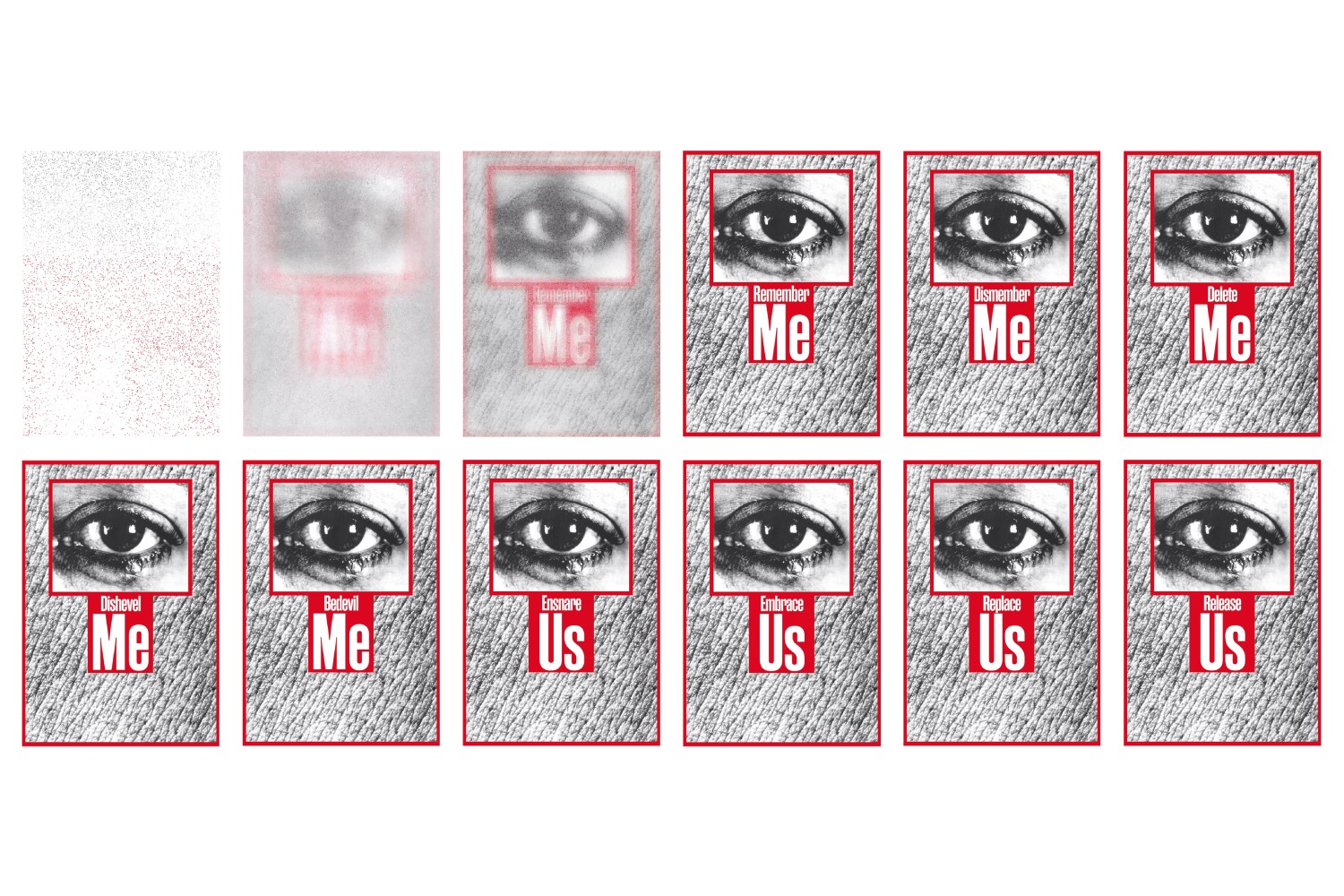

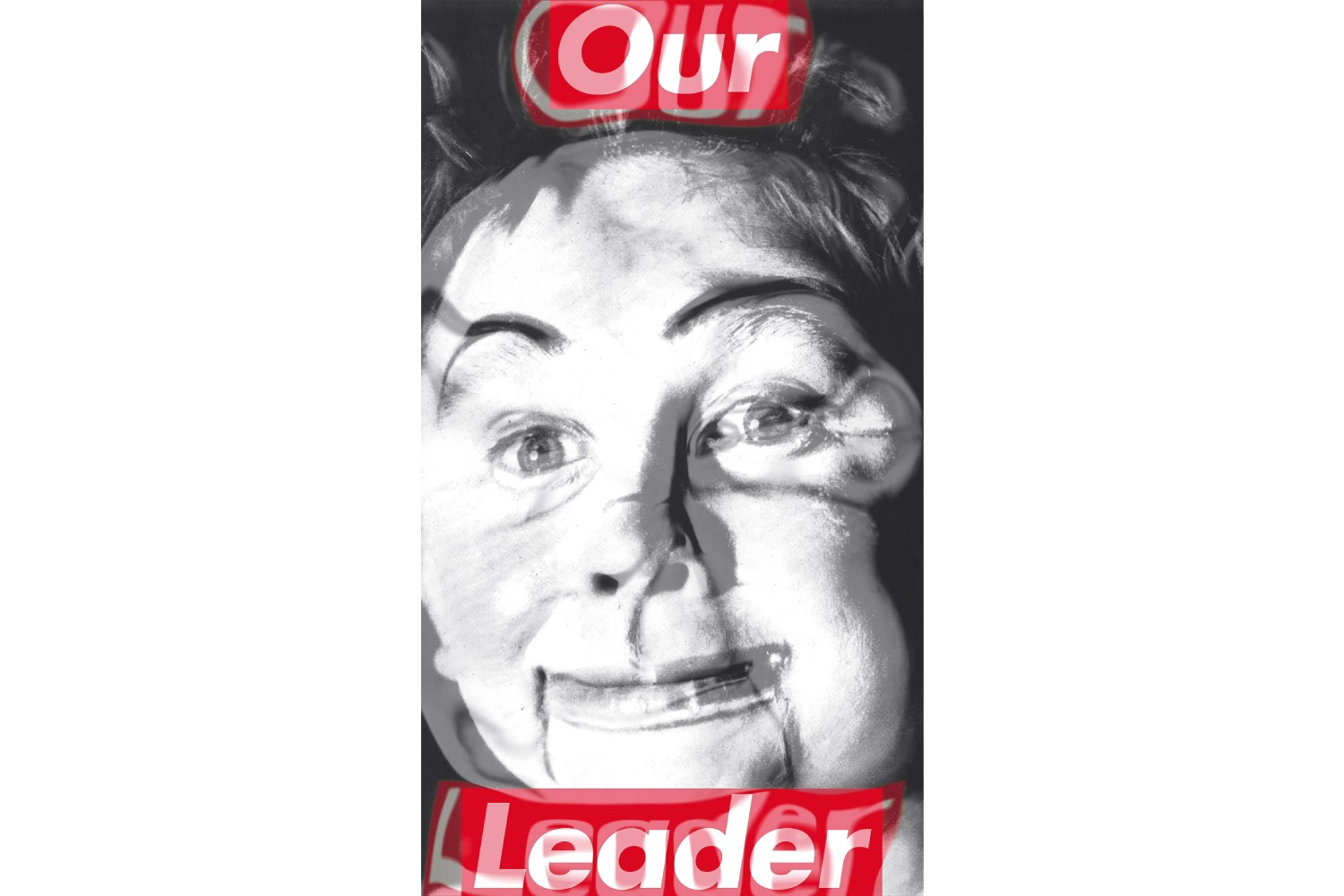

For her current show, “Thinking of You. I mean Me. I mean You,” at the Serpentine in London, Kruger presents recent works including installations, moving-image works, banners, and multiple soundscapes installed throughout the building. Her site-specific work covering the gallery’s first room, Untitled (That’s the way we do it) (2011/2020), comments on digital and commercial appropriations of her work, using imagery of the many derivatives that have appeared in various media since Kruger began gaining traction in the late 1970s.

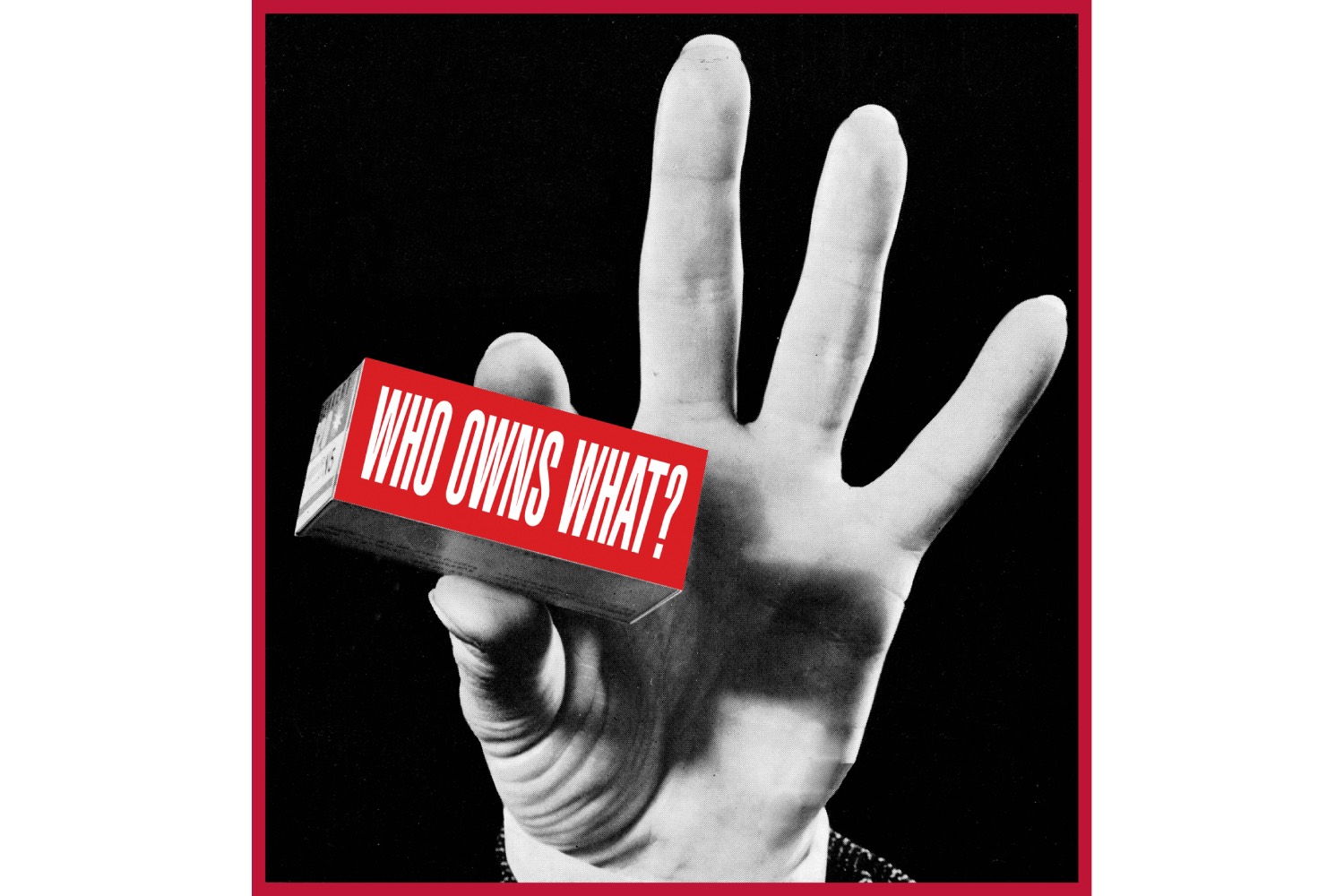

It’s comical and ironic how the very subjects of Kruger’s critique seem to be the ones that step into the honeytrap of internet hypebeast culture. There are myriad examples of this kind of imitation, and American skateboard company Supreme is just one. Their globally recognized logo is the same font and color combination that is used famously by Kruger, and, while the artist acknowledged in The Art Newspaper in 2021, “I think copyrights are euphemisms for corporate control on a certain level,” the instance of this imitation did not go unnoticed. In 2013 she famously referred to Supreme as a “ridiculous clusterfuck of uncool jokers,” and in 2017, as part of the Performa Biennial, Kruger revealed an installation in a skatepark with her signature type interrogating viewers with queries such as “Who owns what?” However, it’s the dissemination of branding that was at issue, and a comment that a critic for The New York Times overheard a young girl remarking at a Kruger exhibition in Chicago, “It’s giving Supreme vibes,” echoes my own sentiments of consumerist recognition. It seems that imitation may not be the sincerest form of flattery.

It’s hard not to feel Kruger anticipated this kind of media dissemination. It’s almost like these imitations were a self- fulfilling prophecy; the more the artist used her specific visual style to comment on our capitalist society’s consumer-heavy nature, the more these imitators seemed to rear their ugly heads. Rather than cast blame, we might admire her prescience. Social identities hold more importance than ever in our age of online media madness and incessant reproduction, while our attention spans are deemed to hold less. In an interview for Musée Magazine in July of 2023, Kruger articulates this perfectly: “The virality of today’s image and info-flow is instantaneous and seemingly never-ending. […] Our online lives can produce pleasure and pain, are both liberatory and shaming, and have the power to remake or end worlds and lives in an instant.” With today’s oversaturated media landscape of celebrities, viral videos, retweets, screenshots, and story sharing, Kruger’s honest combinations of text and images feel more relevant than ever.