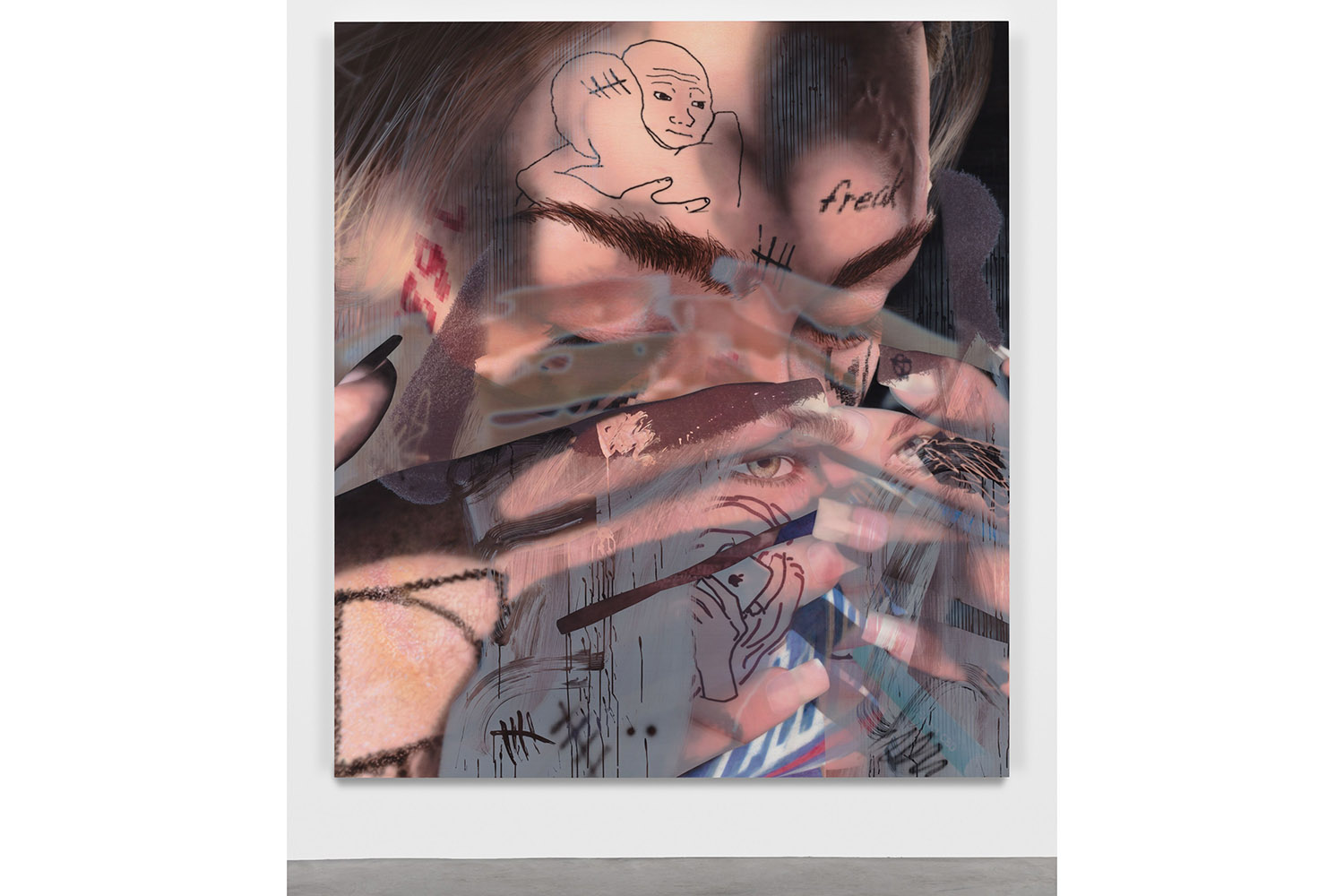

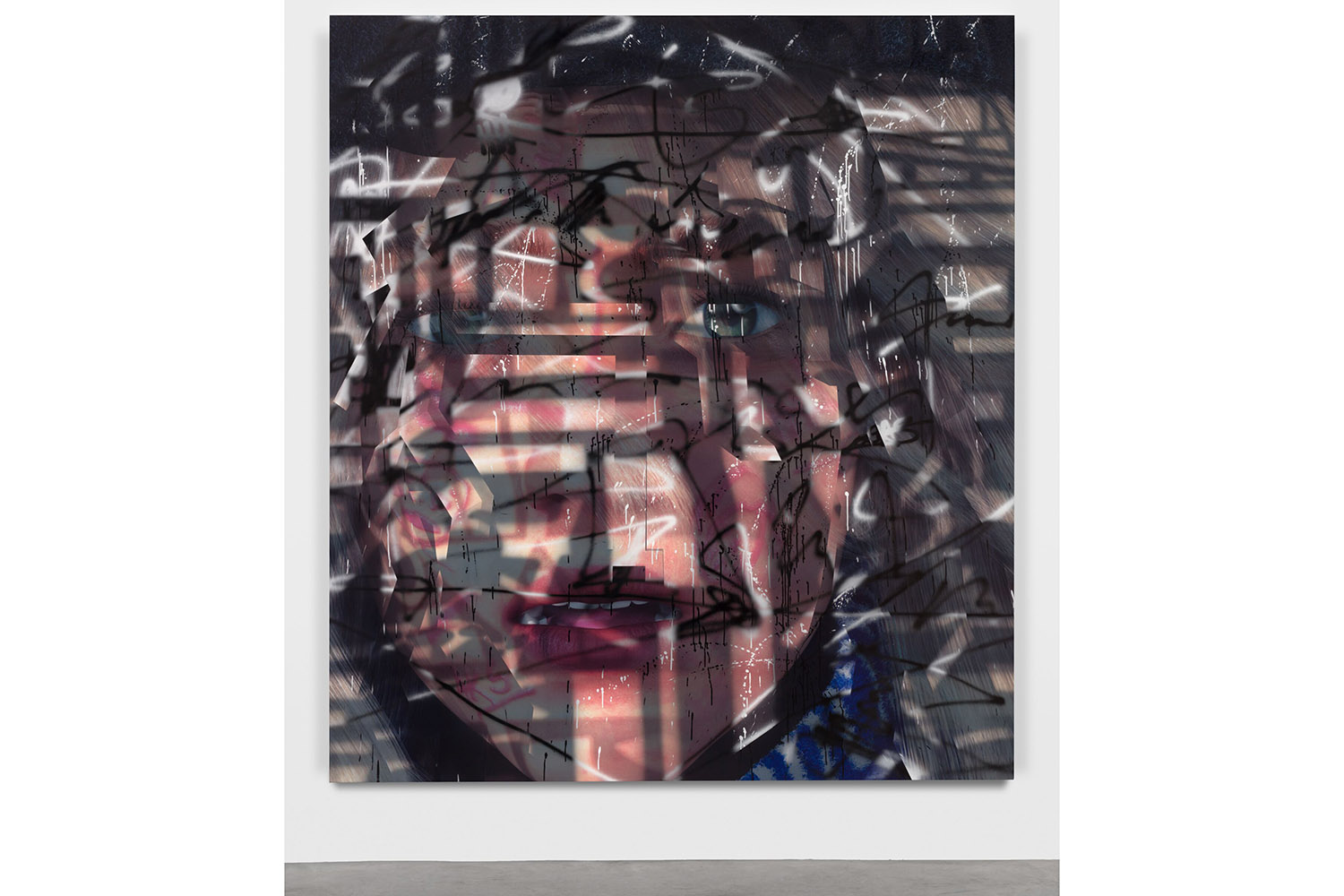

Transfixed by a trio of Avery Singer works under the diffused glow of the Frieze Los Angeles tent, I was somehow reminded of a minor essay by art historian T. J. Clark, titled “Modernism, Postmodernism, and Steam.” It always struck me as a funny piece of writing — more speculative than resolved — even when I first encountered it in the early 2000s while thumbing through an issue of October dedicated to the lofty theme of “obsolescence.” In it, Clark attempts to make sense of the unfamiliar and unruly threads of art contemporaneous to his moment through the dreams of a now-defunct modernism. It’s an odd, anachronistic impulse he traces through the visual motif of steam, somehow linking the ghostly face projections of Tony Oursler’s video installation Influence Machine (2000) to the contemplative visage in Édouard Manet’s The Railway (1873) and even throwing in Picasso’s 1927 Face as an odd missing link. Definitely a stretch, this strange genealogy — faces and steam — nevertheless resonated with the works before me, in particular the aptly titled Heir (2020), a monumental rendering of a woman’s face that could vaguely resemble the artist’s, here dissolving into, emerging out of, or maybe just suspended within a dense cloud of gestures, marks, and cyphers.

For Clark, steam provided a shorthand for the technological revolution that had reshaped the visual possibilities of the nineteenth century. As he notes: “Steam was what initially made the machine world possible. It was the middle term in mankind’s great reconstruction of Nature. Steam is power and possibility, but very soon it is also antiquated — a figure of nostalgia, for a future, for a sense of futurity — that the modern age had at the beginning but could never make come to pass.”1

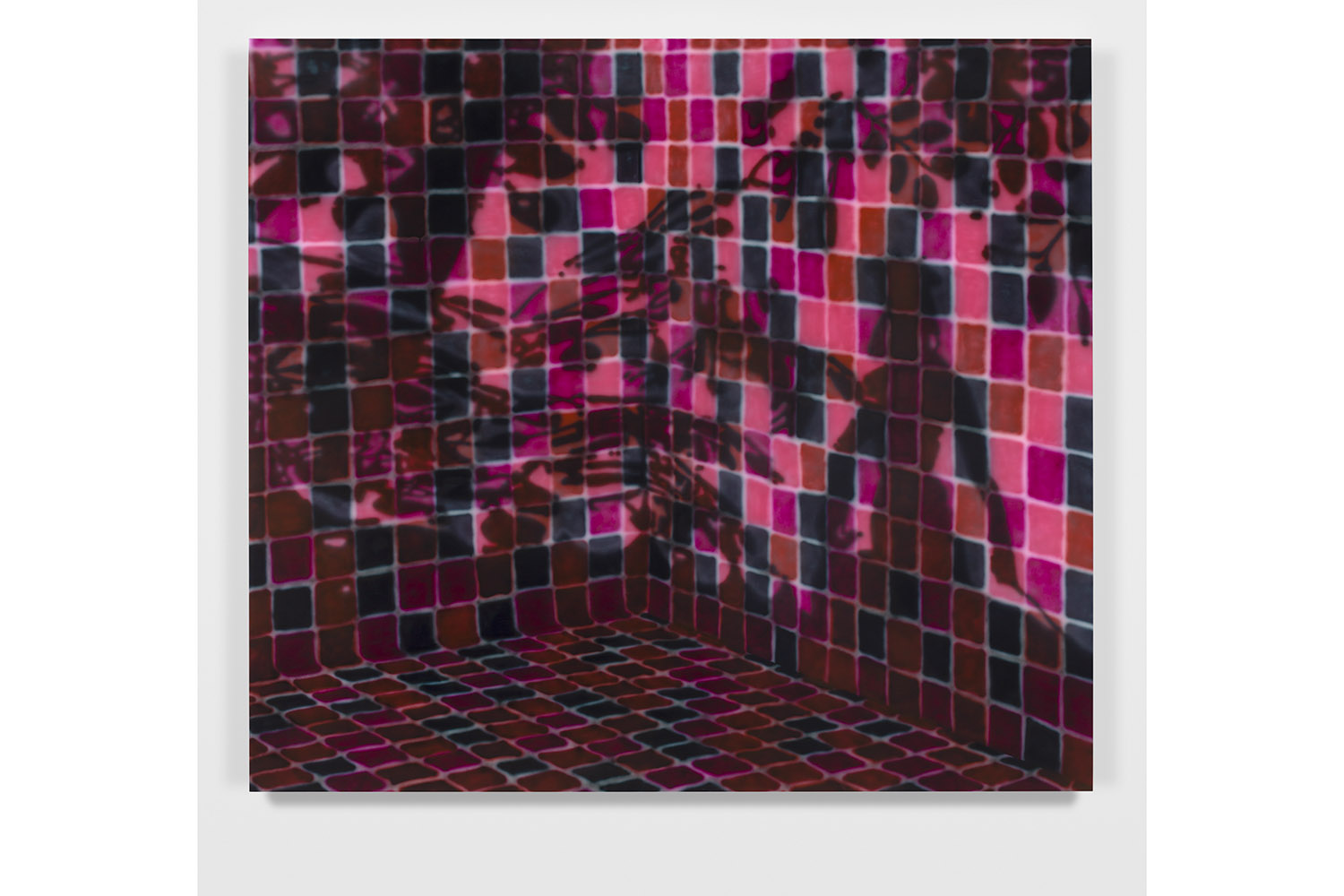

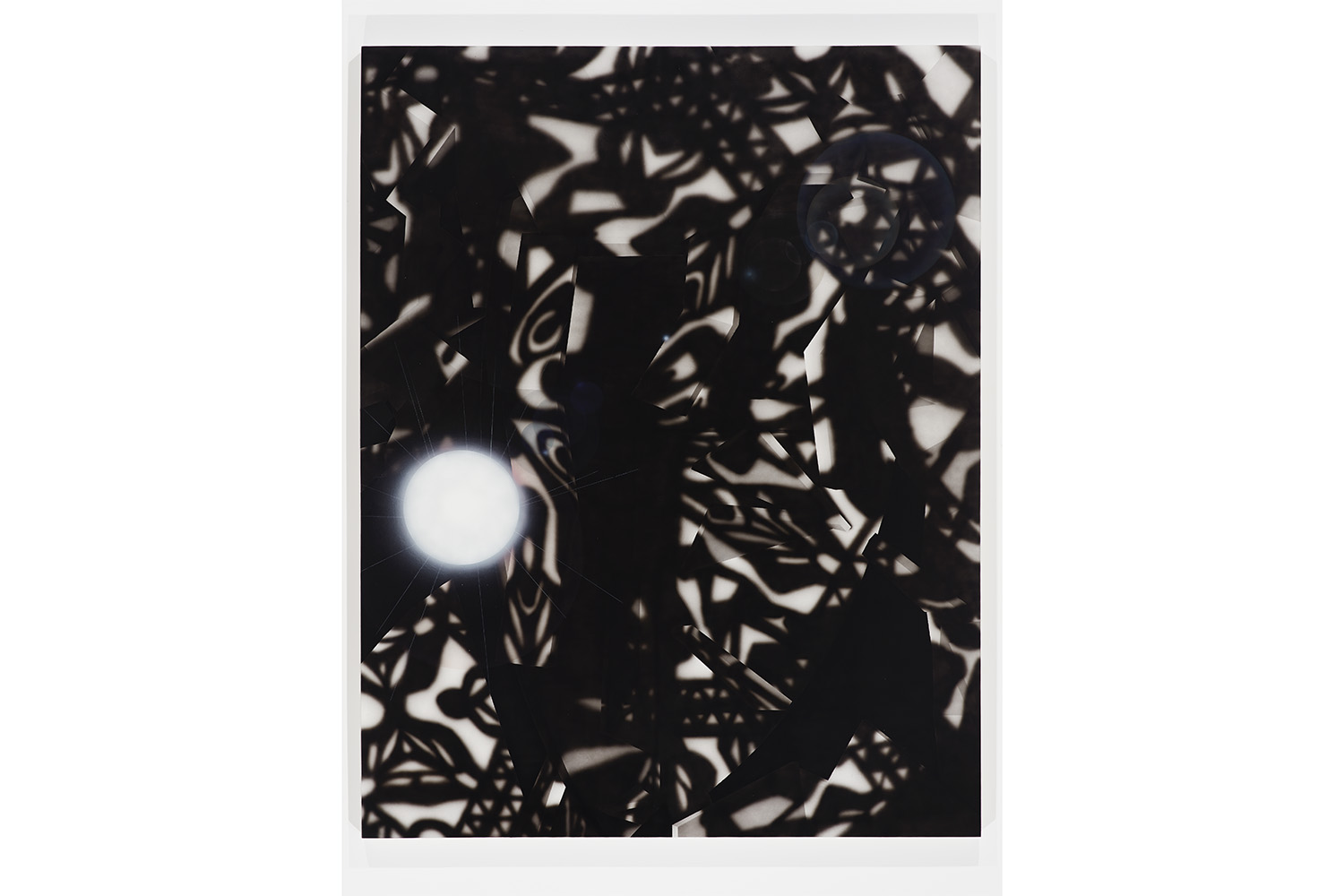

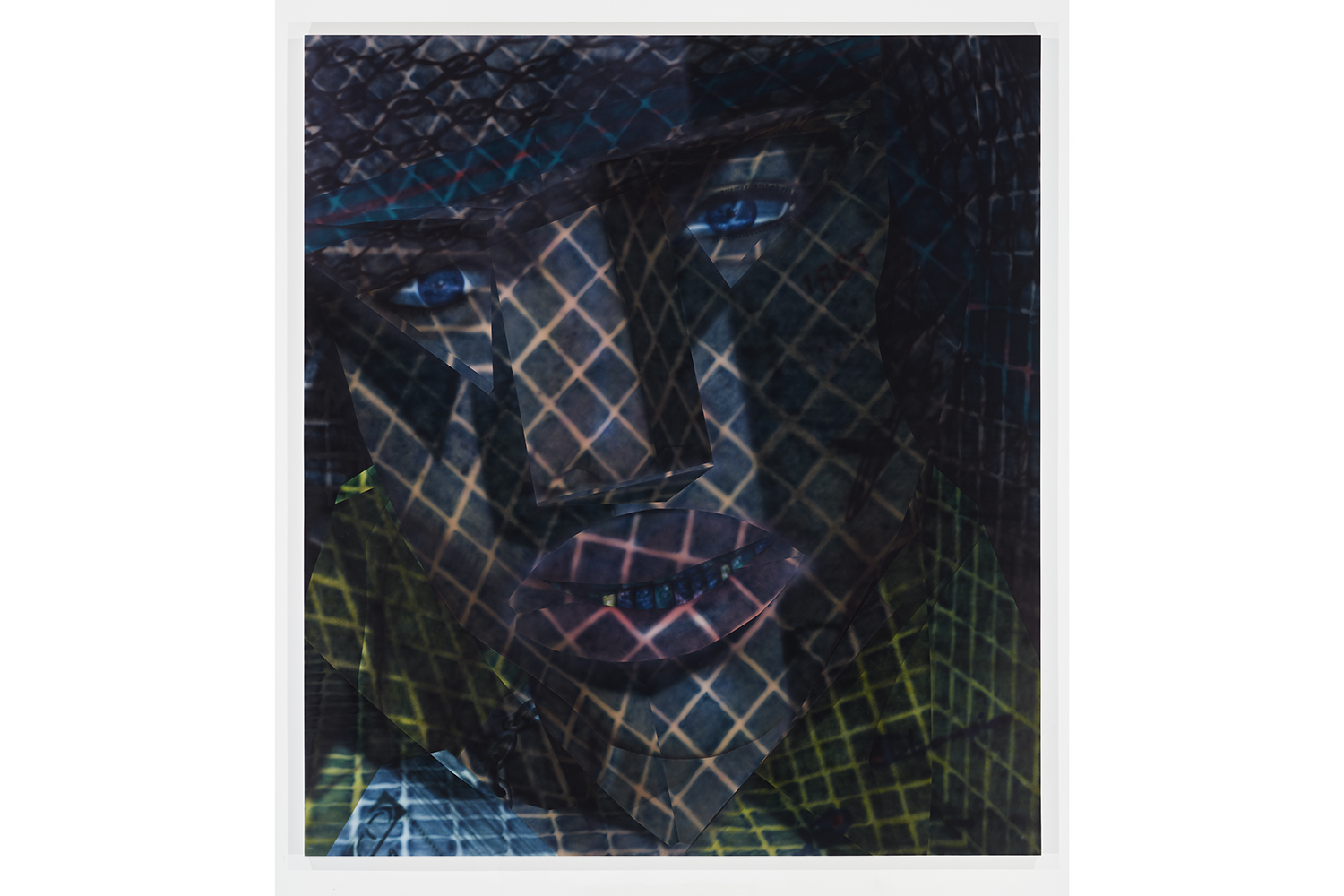

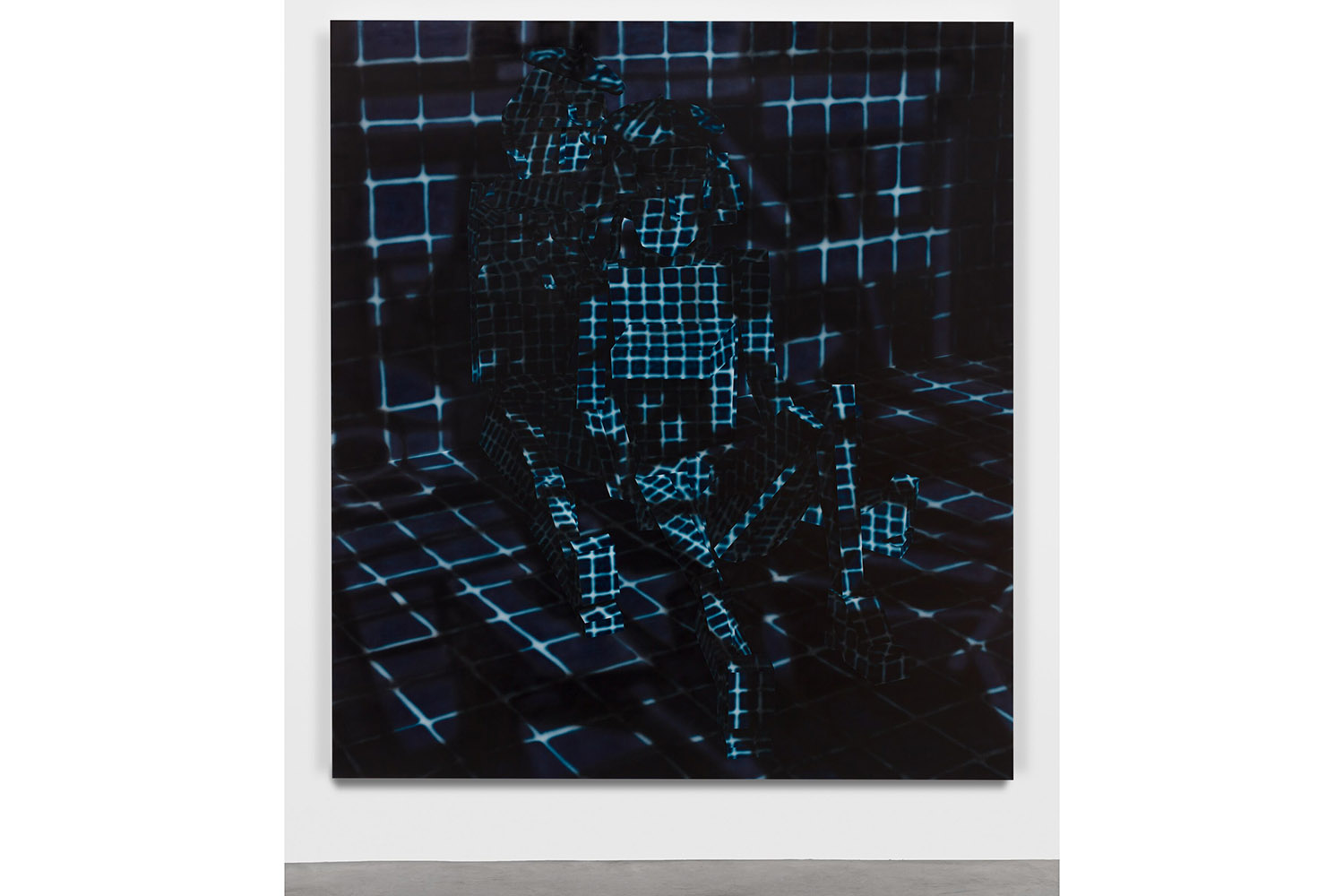

Contemplating Singer’s handiwork amid the din of the present-day arcade that is an art fair, it occurred to me that steam might also be a technological marker for her as well. The motif had become increasingly prominent in recent work, beginning around 2016 and solidified with paintings like Sensory Deprivation Tank (Dangling Feet), 2018, and Sensory Deprivation Tank (Empty), 2018 – both included in the group exhibition “Bubble Revision” at Miguel Abreu Gallery in New York – which depicted her signature Tron-like glowing grids as if viewed through steamy glass panes (complete with trompe l’oeil streaks and drips). The first variation features blocky forms reminiscent of platform shoes, while the second offers up a more uninterrupted view as if gazing at bathroom tiles through a foggy shower stall. More dramatically, there’s Self Portrait (Summer 2018), 2018 — a larger-than-life depiction of the artist doodling with her index finger on the steamed up veil that separates her from the viewer. This work was included as part of a larger grouping in the 58th Venice Biennale.

The unsettling nature of these compositions is hard to pin down — their strange frontality, the indulgence in illusionism, the expanded field of referents (I thought I detect a few surprising if unintentional winks to Marilyn Minter). One thing is certain: as a group they elaborate the almost cartoony, Cartesian space of her earlier Google SketchUp works with something much more disorienting, indeterminate, and diffuse; it’s almost as if all spatial coordinates have been simultaneously dispersed and compressed onto a single, claustrophobic surface.

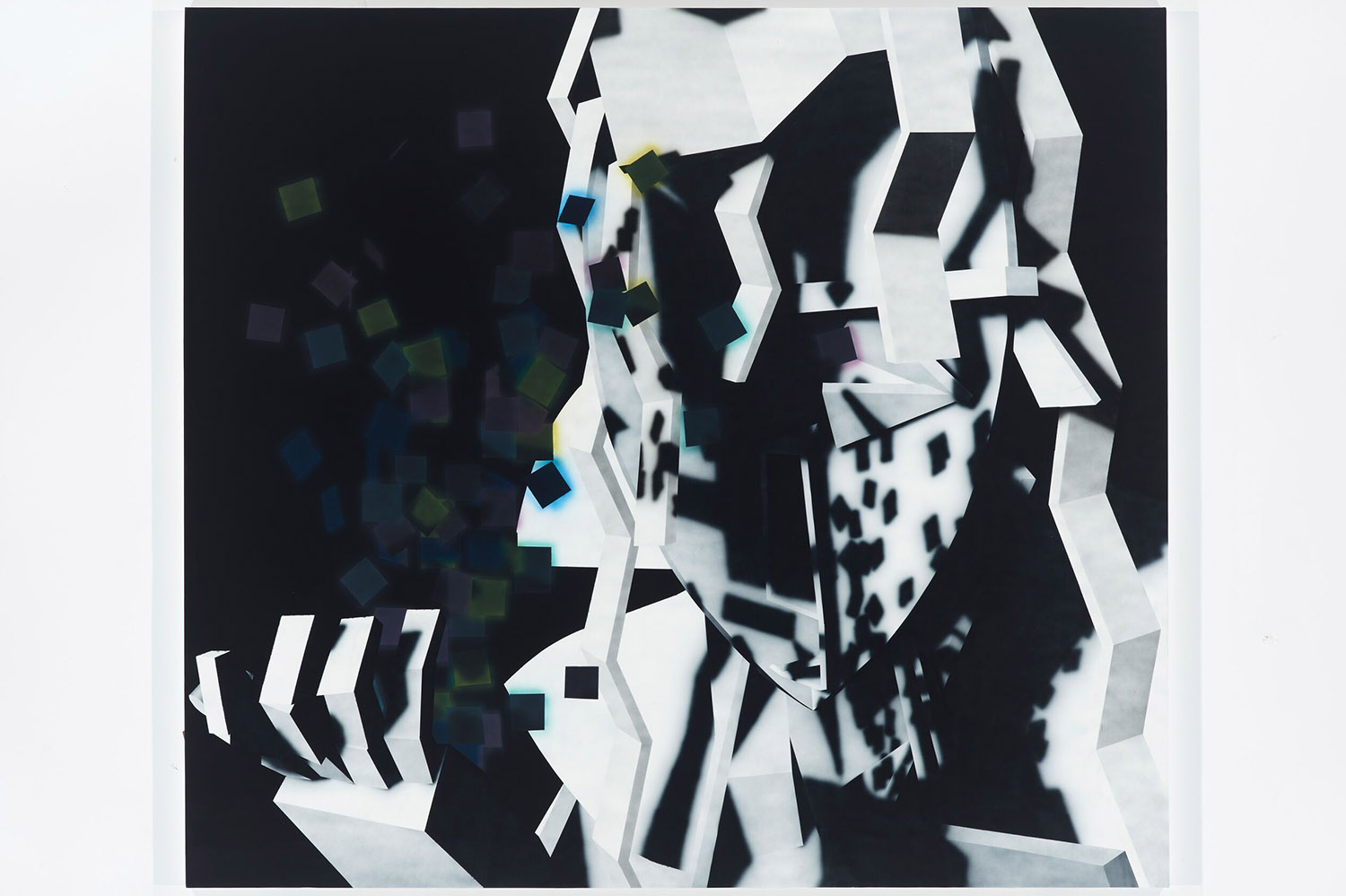

As it turns out, these pieces do bridge the divide between two distinct modes for producing an image — pursued as part of Singer’s larger project of extending “the ways in which artists have removed the hand from painting using technology.”2 The first of these most followers of Singer’s practice will be familiar with: her fortuitous turn to the free 3-D modeling software Google SketchUp, a favorite of many architecture students who use it for preliminary plans. With it, she generated the armatures for compositions populated by rudimentary forms and figures evocative of the digital technologies of the late 1980s and 1990s. Deployed onto a scale once reserved for history paintings, these cubist scenarios provided a radical new way for mapping painterly space in the wake of digital visualization, while at the same time (and somewhat paradoxically) indulging in a type of pictorial nostalgia. After all, at the time of their making, these paintings were already memorials for a visual regime that had long been overtaken by much more sophisticated techniques.

Furthermore, if the computer-based origins of these paintings offered a seductive “hands-free” effect, their realization was anything but. The labor-intensive process required numerous hours of fastidious prepping, including painstakingly tracing the source projection, taping up blocky contours as well as filling them in, layer by layer, with hand-airbrushing, a commercial technique whose uncanny smoothness reads as automated but remains tethered to the movements of a singular body — slight of hand in service of its own effacement. The depicted motifs of bohemian art-historical clichés — many borrowed from the nineteenth century — underscore this intrinsic tension, or more accurately they stage it: the push and pull between an internal pictorial drive and the modes available to making it visible.

Around 2016, something shifted as Singer, through her ongoing research, encountered a commercial airbrush printer, whose most common application was transferring logos onto airplanes. -As its hokey moniker suggests, the Michelangelo Art/Robo readily offered up a more distanced mechanism for image production, whose virtuosity inhered in the very impartiality of its technique. It is a wonder worthy of its namesake, who himself dazzled and unsettled with his painterly prowess. As Vasari mythologizes: “During his stay in Rome, [Michelangelo] made such progress in art that his conceptions were marvelous, and he executed difficulties with the utmost ease, frightening those who were not accustomed to seeing such things.”3

Implicit in this Vasari micro-drama is the idea that vision must evolve and sync up not only to what it sees but also to new forms of seeing. I wonder if some of this was on Singer’s mind when she produced the first works employing the Michelangelo Art/Robo for “Sailor,” her 2016 solo exhibition at Vienna Secession. Seemingly liberated from the exigencies of the hand, these pieces turn, somewhat uncharacteristically, to abstraction, summoning that old bastion of twentieth century modernism, the grid. It appears in numerous iterations, including a glitched-out field, a pixelated expanse of magenta punctuated by cellular dots, and what might be conduit schematics. One tableau in particular maps out a dotted matrix folded upon its phantom shadow, punctuated by seemingly arbitrary blurs of color that could resemble brush strokes or any other sort of painterly mark. On the surface, this sets up a stiff kind of epistemological drama: the grid versus the index, order versus contingency, the technocratic versus the handmade.

Of course, this maps out so neatly that it almost feels like a straw man or, better yet, a punch line. The fact that the painterly haunts a mode of production that could at last be divorced from it makes it all the more so. The joke, as I see it, is that the hand is there all along, just harnessed in alternate capacities, its indices mutated into marks yet unnamed — but also the joke that we might still need the memory of the painterly to process a painting as painting. How ironic is that? Viewed long enough, the brittleness of these oppositions become all the more apparent, their contours as clunky as SketchUp humanoids. Perhaps to pit the hand against the technological as a formative opposition today is its own kind of nostalgia — a projection that disavows the fact that they’re already inextricably and irrevocably linked.

This becomes all the more apparent when you realize that Singer’s deployment of the grid inverts the usual art-historical fable, or at least Rosalind Krauss’s version of it.4 Rather than an emblem of the autotelic in art, a turning away from the mimetic, Singer’s grids are rendered as stubbornly so. They point to all the ways, modes, and filters that define our common lived experience. Far from an ideal Euclidean digital haven, hers is a messier engagement with the material modes through which we attempt to visualize this horizon — and continuously fall short. This is a process that is not fixed but always in flux, dispersing, reconstituting, approaching solid form but also receding from it much like a cloud or — you guessed it — steam.

For me, the complex spatiality of the works produced after “Sailor” offer an analog for this generative instability. They do not set up oppositions, but rather indulge in their dispersal and dissolution. The hand is there all along creating painterly marks as effect, but also inventing new ones, including the veiled or fogged up filter that is realized by carefully applying thin layers of liquid rubber. This very manual build up of the surface both enhances and pushes against what could be perceived as purely mechanical but also sabotages easy distinctions. Perhaps this is why the hand also persists as motif: the artist’s index finger in Self-Portrait interchangeable with the index finger of the mouse hovering over a hyperlink as in Reputation Dereliction On Demolition Island, 2018. The point is that they’re one and the same — or to think of their distinction is no longer a fruitful avenue of inquiry.

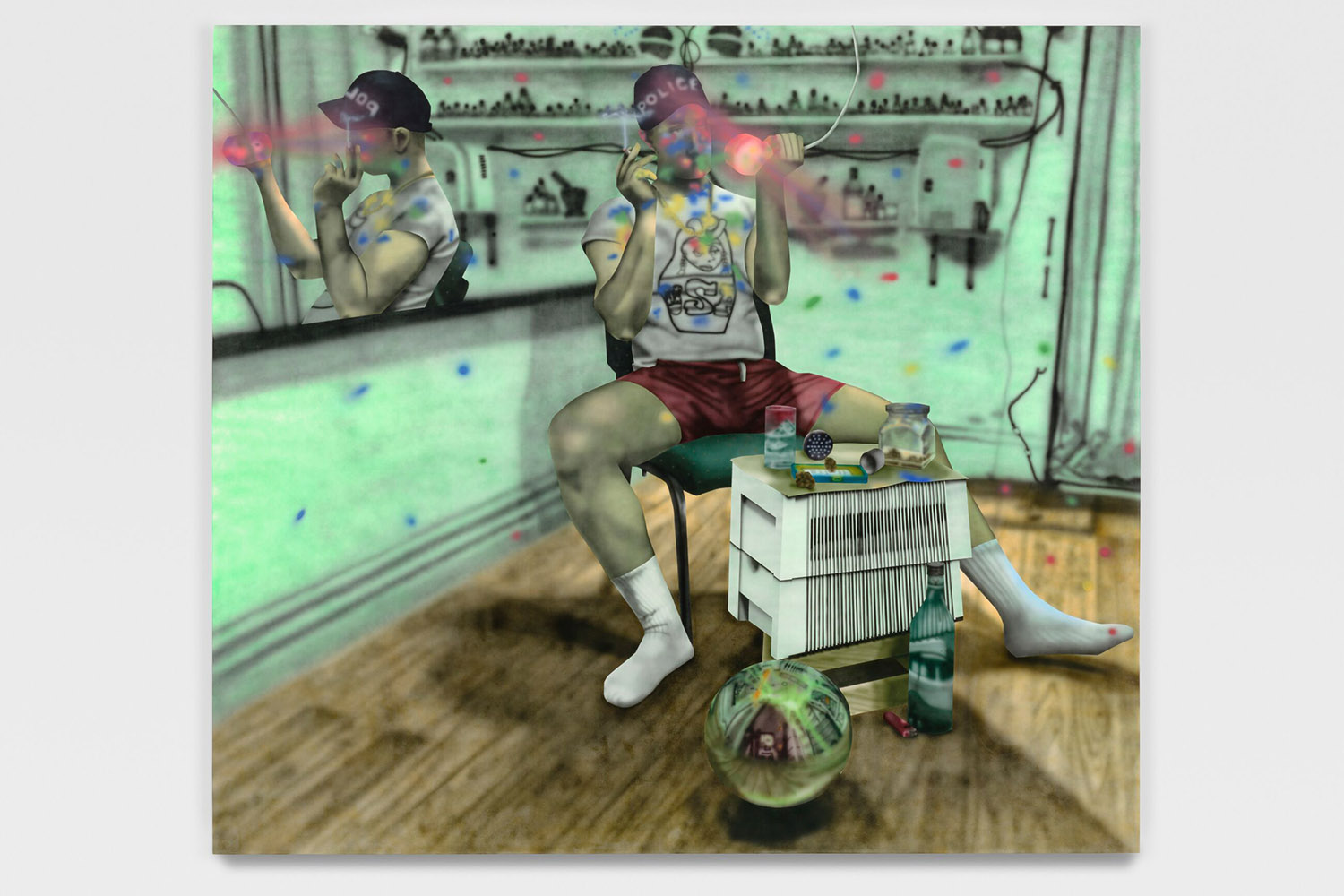

As Clark concludes, the crux of modernism (or at least his steamy version) was not in its endgame but in the questioning that drove it: “Painting in modernism was a means of investigation: it was a way of discovering what it took to make a painting within its limits and put pressure on the deep structure of belief of its own historical moment.”5 Singer’s harnessing of painting extends this questioning to our moment, and she embarks on it with humor and self-parody, offering up a new type of paradigm that I can’t quite wrap my head around yet. This is part of the charm of a painting like Jordan (2020). In it, the artist sits at the foreground (easily identified by her beret) heroically clutching a wine bottle in each hand and surrounded by the efforts of her making. These include not only a vast array of discernable marks and systems, but also phantom doppelgangers — perhaps previous incarnations or discarded avatars each exhausted by their respective plight or simply wiped out from a night of partying — who’s to say? If androids dream of electric sheep, it might be for the same reason that post-analog painters dream of painting without the hand. But then again, at this juncture, that might no longer matter.