A note to the readers: The author recommends We Don’t Trust You by Future and Metro Boomin as atmospheric listening alongside this article, in honor of the album’s subtle infiltration into the Tiffany Sia cinematic universe via exhibition documentation of “Technical Difficulties.

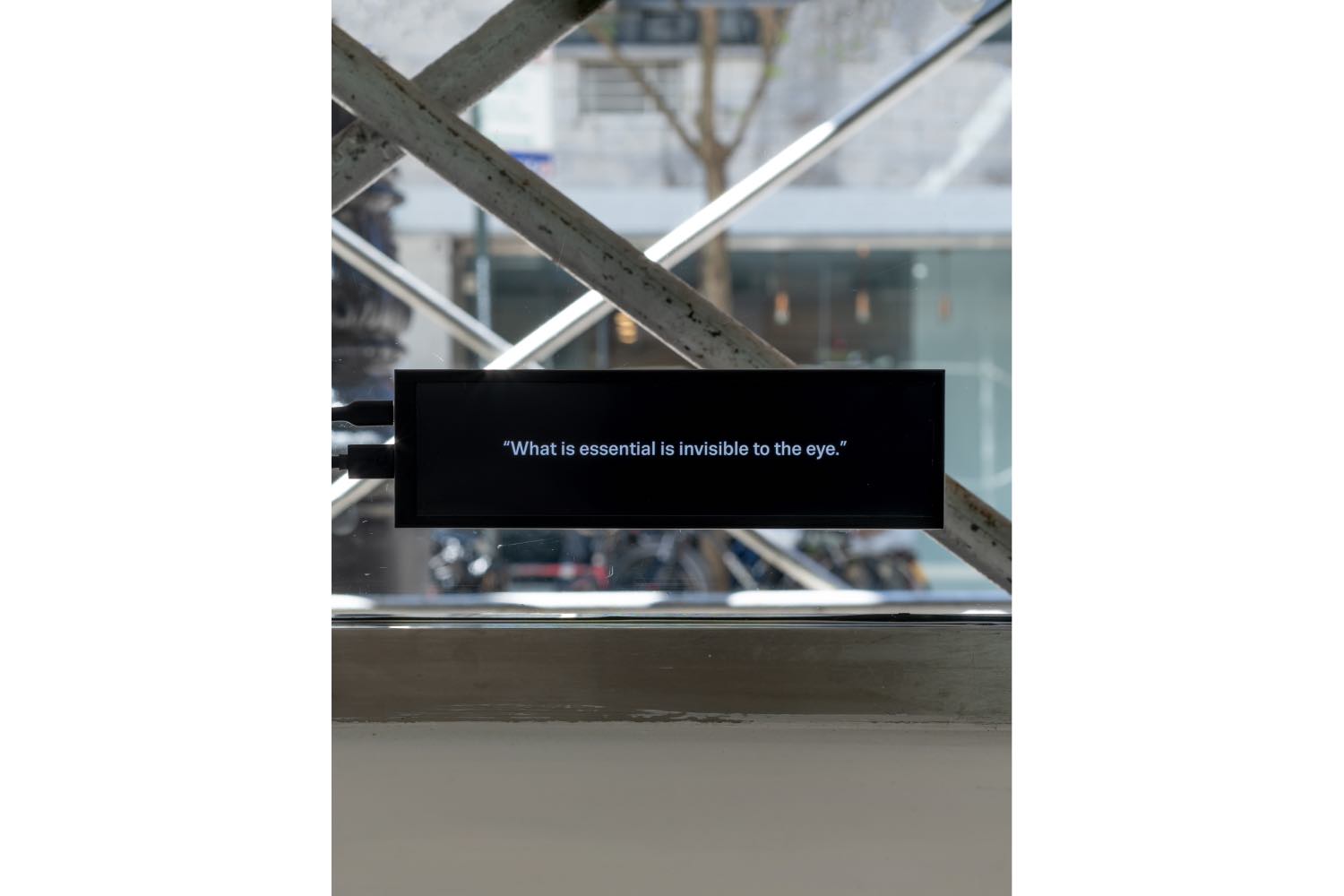

Tiffany Sia’s latest body of work begins with a nonimage. An exterior snapshot of the artist’s 2024 exhibition “Technical Difficulties” at Maxwell Graham, New York, shows only an empty window. While the artist has a reputation for disappearance, the initial formlessness of An Image on Air (2024) amplifies Sia’s invisible ontology of cinema to a new intensity. When its conceit is finally revealed upon entering the gallery, the work invokes Fred Rogers’s 1997 dictum: “What is essential is invisible to the eye… what we see is rarely what is essential.”

Staged as looping flashes of text on a surtitle board mounted inside the gallery’s street-facing window, like a teleprompter or captions for the scene outside, An Image on Air organizes the interior and exterior of the gallery as screened images mediated by the window’s steady frame and glassy surface. The work’s text toggles between historical exposition and first-person descriptions from Marshall McLuhan1 and Fred Rogers2 reflecting on the experience of being broadcast live “on air.” Their comments note the perceived immateriality of the body when rendered as live image: “When you’re on the telephone or on radio or on TV, you don’t have a physical body… You’re a discarnate being.” Through the black box of transmission, to become an image is to become ghostly: disembodied, disidentified, and eternal. By spatially, visually, and phenomenologically restaging the very relations of becoming image, An Image on Air centers the apparatus through which its formlessness is achieved. The body of broadcast is not found in the transmitted image, but in the ancillary infrastructural networks for capturing, transmitting, and receiving images that comprise broadcasting’s invisible vascular system. In so doing, the work resurrects the spectacle of liveness, at once enchanting and sinister, that has been lost in the contemporary era’s screen ubiquity.

The formal lens on media circulation apparent in An Image on Air has been a through line of Sia’s work since the artist’s first institutional solo exhibition, “Slippery When Wet,” at New York’s Artists Space in 2021. The assemblage of work—more an immersive media environment than an exhibition of discrete objets d’art—reenacted atmospheric conditions of technologized visibility and obfuscation in post-2019 Hong Kong. For example, In Plain Sight (2021) arranged small coin-sized stage markers on the floor throughout the gallery, indicating where one would be standing in center frame of surveillance cameras. The subtle Too Wet (2021) visually emulated Hong Kong’s sweltering humidity by modifying windows to appear wet and semi-opaque with condensation. Continuous-feed dot matrix paper, historically used to receive transnational transmissions such as production orders, materialized the paired works The Bastard Scroll (2021) and Bastard Tongue (2021) which, for their visual austerity, made garrulous gestures toward the receipts of history, celluloid film, the visual vernacular of scroll painting, and the affective body of the law. Sia’s commitment to the haptics and materiality of the screened image refuses to let media be misrecognized as the images it delivers.

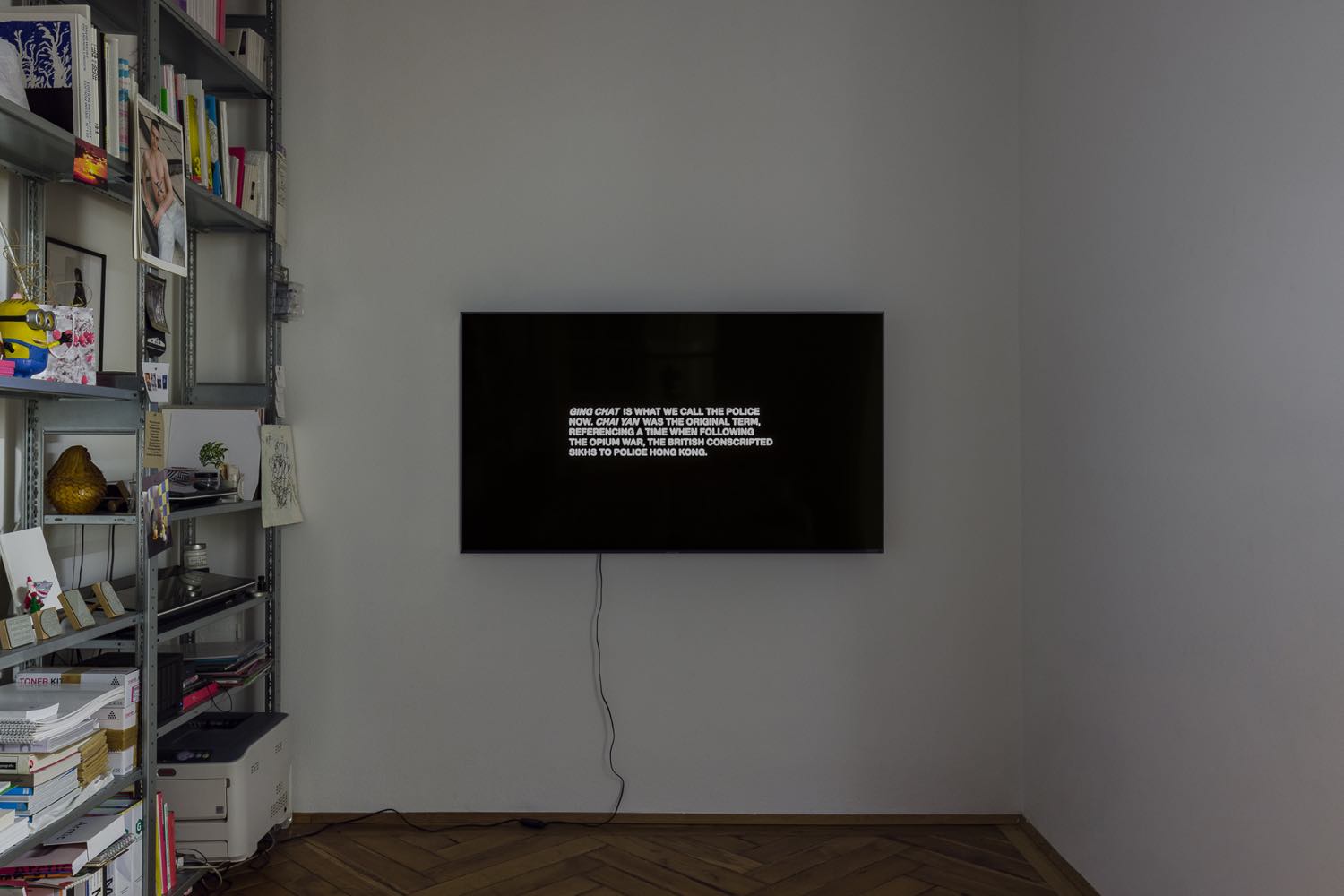

On the opposite side of “Technical Difficulties,” the single-channel video work A Child Already Knows (2024) warns “RECOGNIZABILITY / THEREIN LIES THE RISK OF USE.” The short film—which has been screened cinematically in programs on landscape cinema and unrealizable films—simulates a television flickering with animations from the Shanghai Broadcasting Company during the period between the Sino-Japanese war and the Cultural Revolution intercut by titles recounting a child’s memory of escape southward from Shanghai. Rumbling train sounds texture the account. The familiar content of the cartoons — vegetation changing with the seasons, the hero-villain exploits of anthropomorphized animals — conceal their role as proxy for Sia’s father’s childhood, a memory impossible to return to or reenact, and only partially accessible through oral history. An interstitial “///” periodically connects image fragments, shards of memory, and the artist’s editorial interjections, foregrounding the work’s announcement that “the real film is neither here / nor here / but in its interstices.” While the seduction of text is its promise to contextualize image, Sia’s unyielding “///” reminds us of what remains exiled from record altogether by deflecting attention to the fugitive elsewhere of memory. The work narrates toward a history that never congeals, instead chronicling elisions produced where history’s unruliness exceeds the forms available for its portrayal.

Parallel to the paternal memory of A Child Already Knows, Sia’s earlier work What Rules the Invisible (2022) mobilizes recollections by the artist’s mother as its subversive genesis. The video remixes official narratives of Hong Kong visualized through travelogue footage by weaving it with a subterranean oral history of ghosts, waste, and rituals of domestic life. While the forms of each work at first appear similar — found footage accompanied by personal accounts in text — subtle differences in the implicated publics of each work’s source material (the child’s versus the colonial gaze) and the temporal relations of each historical retelling set the rhymed works apart. If A Child Already Knows is interested in the impossibility of reenactment, What Rules the Invisible explores the distinctions between official and unofficial record, probing for that which is obscured by the tried-and-true image. Private histories relayed by Sia’s mother and oppositional gazes from unwilling ethnographic subjects puncture the film’s tropic images as intertitles, rubbing up against images of public space that travel on the currency of their familiarity. Where faces and bodies blur from the loss of fidelity accrued with circulation, shots of the skyline or junk boats in the harbor remain everlastingly recognizable. A Cantonese folk song closes the film with no translation in what is suggestive of the minor forms of knowledge that remain unscalable and circulate within intimate publics through generational transmission.

Throughout her practice, the tension of Sia’s work lies in the challenge form poses to its own examination. How do you make work about form? What form does it take? In a conversation toward the writing of this piece, Sia shared a screenshot of page 47 of Fred Moten’s Black and Blur (2017), where Moten quotes Glenn Gould, saying, “One must try to invent a form which expresses the limitations of form, which takes as its point of departure the terror of formlessness.” Sia’s 2024 book On and Off-Screen Imaginaries offers to the dialectic of form and formlessness the vocabularies of “elliptical montage” (a poetics of possibility in the intervals between images) and “no place” (places that exist only in imagination or have been rendered unknowable by violent transfiguration), which position her formal strategies in a lineage of what Pavle Levi has theorized as “cinema by other means.”3 Sia’s emphasis on cinema beyond the image — ghostliness, absence, invisibility, interstices, intertitles, accessibility measures, circulation infrastructures, and imaginaries represented or produced therein — wades into formlessness by tracing cinema’s asymptotic relationship to memory. Sia’s work homes in on the economy of disclosure and obfuscation that underlies the very structure of cinema by occupying the ellipses, failures, and refusals of representation. Her work thus takes as its form that ever-narrowing space of desire where memory keels toward a horizon of actuality that can never be reached.

Sia notes that her recent body of work finds a companion text in Wim Wenders’s Alice in the Cities (1974). The film takes the form of a road movie in which Wenders’s self-insert protagonist meanders through the ultimate sameness of small-town America. He steeps in New York’s alienating urbanity before returning to Europe, where he must chaperone a child through the postwar German countryside in search of a familial guardian to take her in. Alice echoes the vulnerability of a child at the whims of adults in their life that is conveyed in A Child Already Knows, as well as the generational alienation caused by historic rupture. Meanwhile, protagonist Philip shares Sia’s suspicion of seemingly easy images: “No image leaves you in peace; they all want something from you.” He repeatedly lays out his Polaroids in sequence, like cinematic frames. At one point on the road, moments of somnolence, television spectatorship, and monotony-induced road hypnotism blur together until our proxy guide begins to close his eyes even while driving. In another moment, narrating his line of vision on the road, Philip remarks, “It’s more like listening than talking.” In these liminal spaces between cities, where Philip and Alice stay on the move, senses fold in on one another, and the direction of image generation and consumption grows confused. That is, as in Sia’s work, the film’s thesis leaks out in its interludes.

Alice in the Cities’ routing of generational memory through landscape rhymes with Sia’s habit of limitless wandering, which the artist scales to sweeping dimensions in A Journey from North to South (2024). For Sia, landscape and geography serve as the medium through which imaginaries of place, nation, and belonging, as well as speculation for extraction and capture, are cathected. Landscape connects personal and collective scales of memory, and endures as a visual vocabulary across diverse traditions, from the inked panoramas of scroll painting to the open terrain of road movies. Landscape is both the object of record and a record itself. It affords multiple views, modes of traversal, and mythologies.

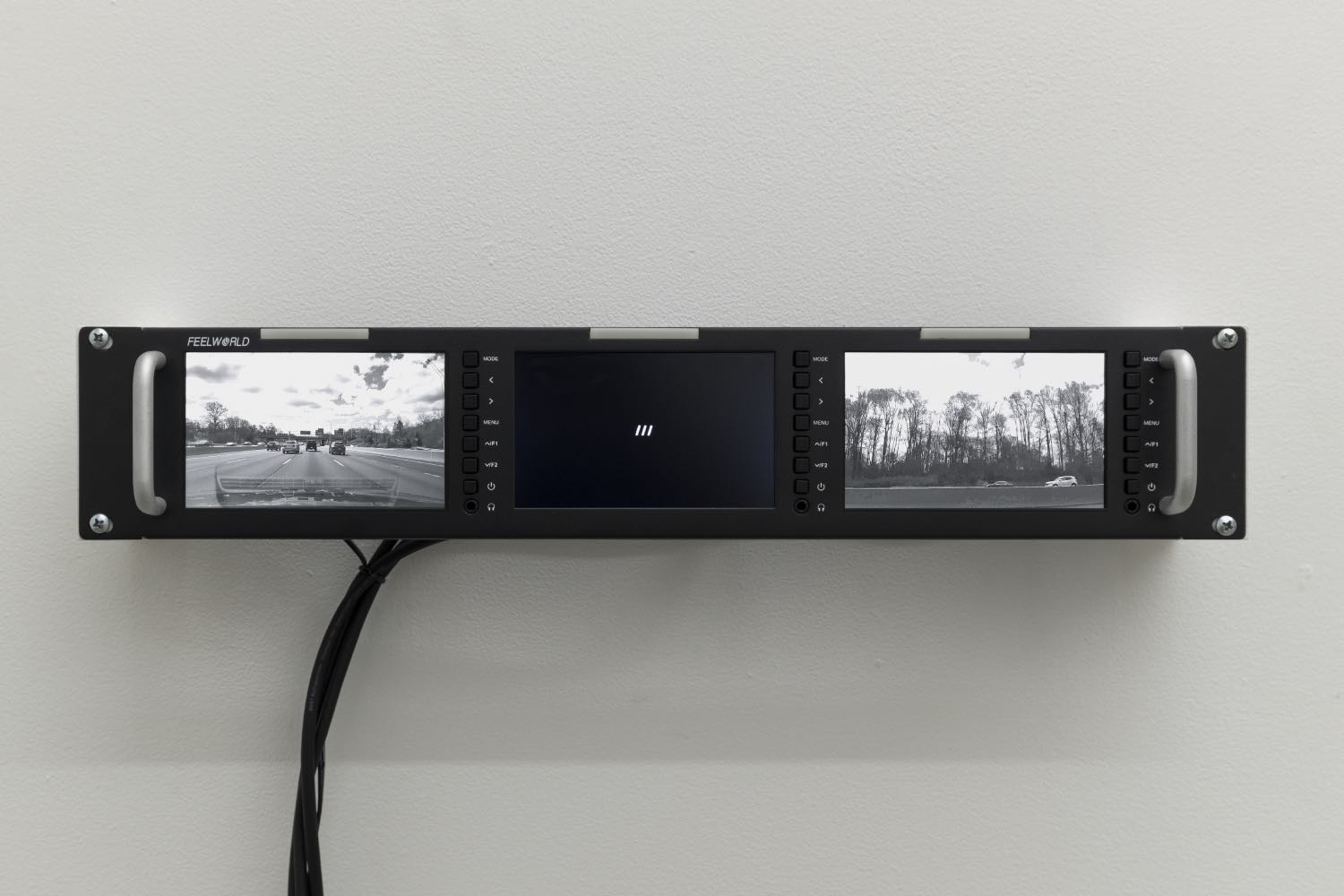

In A Journey from North to South, landscape is the media and media is the landscape of memory. Composed as a video installation on a three-channel rackmount monitor, it shows road footage from two perspectives in black and white separated by the familiar “///” suture. The left screen shows a view out a car’s front windshield, hurtling into the depth of the image, while the right screen displays the side-scrolling view seen from left side of the vehicle, reminiscent of a film strip or scroll painting sliding past. The footage follows the artist’s twenty-two-hour drive from New York to Biloxi, Mississippi on the Gulf Coast, an expedition that reenacts her family’s 1958 escape from Shanghai to Hong Kong. In this sense, the South of Sia’s journey is multiply doubled: the work not only renders the ever-disappearing landscape in dual perspectives, but also configures one southward passage as proxy for another, transposing the Chinese South of generational memory into American Southern geography. Though this other South makes no explicit appearance, the artist’s detour through the Mississippi Delta region, stopping at the Greenville Chinese Cemetery, gestures toward Chinese diasporic affinities linked by shared deltaic topographies: the Pearl River and Mississippi River deltas. If cinema is of the mind anyway, as A Child Already Knows suggests, perhaps the space the work outlines between deltas makes the translation of memory therein affectively possible, even where reenactment remains out of reach.

A Journey from North to South’s physical scale as an installation trades the dramatic sense of a mythic, sprawling landscape one might expect of a road movie for a more subtle sensation that foregrounds the apparatus of encounter. The configuration of the video work for a rackmount monitor suggests a film in production, on the road and forever unfinished, consistent with her practice’s broader interests in exploring the form and infrastructures of media production and circulation. As it proceeds with increasingly staggering endurance, the work becomes defined by an inverse relationship between showing and telling. Through its duration and continuity, the work offers a relentless topographic description, but in doing so, warns against mistaking comprehensiveness for transparency. Despite the duration of footage, the places Sia traverses never truly open up to those passing through. We remain, with Sia, on the road.

Sia’s meditation on landscape, the road movie, and scales of looking come crashing back to form through the sculptural force of her “Antipodes” series (2024). In each iteration, a rearview mirror, suspended roughly at eye level by a long beam from high ceilings, displays twenty-four hours of recorded live-stream video of historically militarized sites in the Pacific such as Okinawa and Kinmen. Here, the rearview mirror stages a personal intimacy with the screened image, gesturing toward the sublimation of surveilling and sentimental gazes. The tonal contrast between the landscapes’ inviting beauty and the viewing apparatus’s machinic coldness only heightens this effect. Dichotomies of liveness and record, past and present, come into tension once more. Indeed, the series title, which refers to parts of the earth diametrically opposite one another, suggests dialectics as a method of analysis while also self-citing a previous work, A Road Movie is Impossible in Hong Kong (2021), which used temporally antipodal positioning as its point of departure.

With its rhythmic returns to select forms, concepts, and histories throughout, Sia’s montagic practice composes a cinematic universe of its own, rich with intertextual self-referencing, spatiotemporal interpolations, and promiscuous blurring of history and memory, imaged and imagined. Through this choreography of oscillation, dis-/reappearance, and reencounter, launched within individual works as well as the meta-narrative of Sia’s broader practice, formlessness as a form in and of itself draws ever so slightly nearer in vision’s peripheries.