Valentina Sansone: You attended the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts during the ’90s together with Katarzyna Kozyra and Paweł Althamer.

Later on you collaborated with Paweł Althamer on the video So-called Waves and Other Phenomena of the Mind (2003-04). While watching your video An Eye for an Eye (1998) I noticed a close relationship with Kozyra’s work: the body expresses a state which is also a social condition. Can you tell me something about those years in Warsaw?

Artur Żmijewski: Those years in Warsaw were extremely vibrant and carried a promise of change, and artistic actions had an almost purely political context. The ’90s were a time when the future shape of the Polish society was being determined. Poles emerged from under communism, it seemed, decapitated. Society seemed completely malleable. It seemed every resentment or complex from the past could be reduced to the homo sovieticus formula and removed like a tumor.

At least two important social projects were proposed at the time. The first one was promoted by the democratic opposition community focused around Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland’s leading daily newspaper launched initially for the June 1989 elections. It was a liberal project, promoting a free-market economy and pure capitalism as the main economic mechanism, but combined with cultural conservatism — for example, visual artists were like enemies. People who wanted radical political changes looked at artists as if they were madmen — and yet the radicalism of action, of language, the desire for change were no less intense in art than in politics.

But, of course, it was a kind of tactic — the economic transition was a major shock so, as a compensation, it was necessary to make people believe that the authors of that shock were at least as conservative culturally as the rest of society. Government supported by media introduced the past and started a new economic order. Thousands of people were lost in this new deal — culture, especially visual art, was used as a scapegoat. Art was the reservoir of cultural perversions and scandals that could be vetoed in order to declare one’s own conservatism and to maintain continuity with the people who were victims of economic change — that is, with the majority of polish society.

Yet culture, the artistic world, offered its own social project at the time. It was a project of social development that could have complemented the economic and political projects — the model of social change in this project was transgression — an abrupt, nonlinear advancement. Exactly what was happening in the economy. And culture, with its major social project, fell — sacrificed on the altar of economic transformation. Isn’t it so that culture suggests formative projects to society?

Transgressive artistic behavior is a model of abrupt, nonlinear development, for instance, of civil and cultural liberties.

During those years I studied at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts — together with Paweł Althamer, Katarzyna Kozyra, Jacek Markiewicz, Jacek Adamas, Katarzyna Górna and others. Those were, and are, fascinating people — some of them devoted their lives to art, even though their predisposition wasn’t really artistic. Paweł Althamer, for instance, is a medicine man, a healer, but the therapies he conducts are only possible in the field of freedom designed for art. Katarzyna Kozyra similarly — she is a terrorist, setting off her social bombs, operating so as to cover her tracks from the field of art. But isn’t it a broader phenomenon that people equipped with non-standard skills find a field for their application in art, culture? Their skills refuse to be squeezed into the grid of rational or ethical obligations, such as scholarly methodology or ethical responsibility.

VS: How did you meet Danuta, Dorota, Alina, Giuseppe and the rest of the characters featured in the homonymous series of documentaries [Danuta, Dorota, Halina, 2006 and Aldo, Giuseppe, Salvatore, 2006]? Did you select them on the grounds of their employment or their social class?

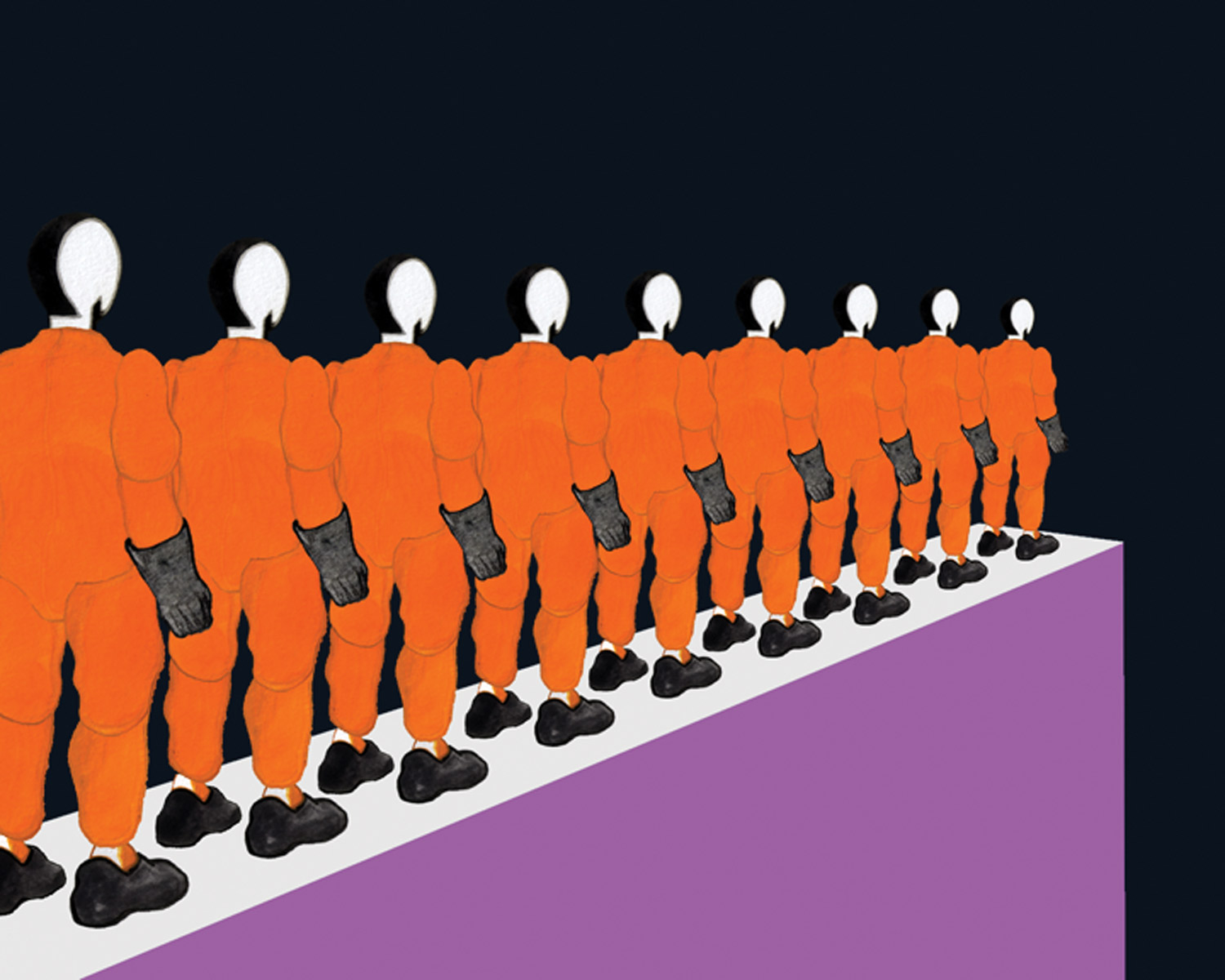

AŻ: I looked for them in places where people work by performing simple physical tasks. At an assembly line, or at a checkout in a supermarket, the actions are extremely repetitive and the days are really the same. It’s fully acceptable to declare in public: “I’m a lesbian, I’m gay or I’m ill with a brain tumor.” Even if you say: “I was a heroin junkie,” members of the middle class are ready for your confession. But what if you are a construction worker or a cleaning lady? What if you are an immigrant worker and you are not educated? That kind of coming out is shameful. So, I met these workers and I tried to persuade them to appear in the film, to show their world — to break the silence. The lower classes, as we know, keep silent to avoid becoming an object of ridicule. But it isn’t their world that’s ridiculous, it’s us, the privileged classes, that dismiss their statements as ridiculous and stupid. But when it came to changing the system — replacing the People’s Poland communist regime with a genuine parliamentary democracy, the front line turned out to be in the shipyards and coal mines. Because the people from there can’t afford to go into self-imposed exile. But when the systems changed, a time of contempt began, and the middle class speaks of those people as of the dim “masses who can’t see further than a piece of sausage.1” So all those invisible lower-class people suddenly appear in this series, in all their degraded beauty, and say, “Here we are, notice us!” Because our world is no longer a good place for producing difference. Difference is an instrument of power. Of course, society is structured by differences, but on the other hand our world suffers from an excess of power, an excess of cynicism, excluding politics, which is based on differences.

VS: In Repetition (2005) you present an experiment that was conducted by Professor Philip Zimbardo at the Stanford University in 1971. Among your films, I think this is the one with the strongest tension. Everything is perfectly defined, starting from the casting. What criteria do you use for the selection of the actors?

AŻ: Yes, it was an extreme experience for all the participants, including for some members of the film crew. For a whole week I slept for two hours a day, lived on coffee alone, didn’t feel hungry. It was a great unknown, we were following a situation that was progressing, but nobody knew where, a dangerous situation — we were on the edge all the time.

Philip Zimbardo produced knowledge I wanted to dispute — the power of his experiment lay in programming us into believing that people put into a position of authority will inevitably be corrupted by it and will become tyrants. That’s how the ’70s US psychological experiment worked. It engraved itself in our minds as a permanent disposition for making always the same, cruel choice — exercising cold, cruel power — it confirmed and cemented the supposition. Such excess of rightness is something you should polemicize in art. Zimbardo in a way put a curse on the experiment of his — he kind of forbade people to repeat it, claiming that would be unethical because people suffer in it. So repeating the experiment, his argument went, would be mean and contrary to psychology’s aim of working ethically towards human welfare. The prohibition, of course, did not prevent the malicious knowledge, malicious software for our minds, produced by the prison experiment, from self-replicating itself. That malicious software needed to be recognized as a virus and treated with a vaccine. For it turned out, following the Abu Ghraib scandal, that people can be not only “ordinarily evil,” but also “ordinarily good.” The cynicism of the science is clear — repeating the Stanford Prison Experiment is forbidden, but the course of events during the experiment and also results of it are part of a basic psychology studies.

I asked psychologists for help when interviewing the volunteers for the experiment — I wanted people who were, say, normal. Average, without any psychological problems, etc. After all, it was supposed to be an experiment on the majority.

VS: In Them, the video you presented at Documenta 12, you put people from different ages and backgrounds together, making them live in a totally anarchist environment. Eventually, everything ends up being destroyed. What were you expecting from this experiment?

AŻ: This wasn’t anarchy — from the very beginning, the participants had accepted the basic rule of democracy — that other people can interfere with the symbolic orders they identify with, with the views they subscribe to, can rewrite them, modify them, even radically alter them. This was done using a language different than usual — instead of words, they used images, the language of visual communication. What may appear as destruction is in fact a means of carrying out a debate, and ultimately results in the removal from the ideological landscape of content or identifications that block development — rigidly defining the boundaries of the participants’ political capacities. So you shouldn’t view the game as being destruction-oriented.

You should view it as a debate, where some arguments collapse under the weight of other ones, and in the end the whole ideological landscape is reset, opening itself to new knowledge. This is an experiment based on unleashing political urges, expressed in a language not of political correctness, but of an ideological subjective truth — confrontation, antagonism. As someone nicely put it, this film is a “thermometer stuck up the Polish society’s ass.” We shouldn’t extinguish this political passion by calling its effects destructive. Instead, we should fuel it by inventing and handing over to people new instruments of political expression, by enfranchising people politically, turning them into political subjects.

VS: During the 5th Berlin Biennale you worked in collaboration with Sławomir Sierakowski. Did you collaborate with other artists in the past?

AŻ: Sure, collaboration is useful. It frees us from the constraint of individualism and amplifies our voice. Because in art, you can only be an individualist — the only acceptable cooperative is the artistic cooperative. The artist is supposed to be a loner, an individualist possessed by his own ego, always manifesting his aversion to the crowd, to things ordinary, to that which the majority shares. On the one hand, this pushes the artist into loneliness, but on the other, it makes his voice stronger.

Because the artist’s voice weighs more than that of the man in the street — in some mysterious way, it equals the voice of the community.

Sławek Sierakowski is a politician, but that collaboration was also useful. We tried to mix the orders of politics and art, science and art, and so on. In politics, you have this element of risk, of the unknown, a sudden decision that creates a new reality. And art is something like that too — every artistic gesture summons some new existence into being. It’s reality forming.

VS: In your “The Applied Social Arts” essay [Neue Berliner Kunstverein exhibition catalogue] you write about when parliament members Witold Tomczak and Halina Nowina-Konopczyna intervened on Maurizio Cattelan’s La Nona Ora. What happened?

AŻ: This essay is an attempt to draw a strategy for an art that has an ambition not only to ask questions, but also to give answers. An art that analyses the impact it makes, that is sometimes selfish and local, and that is interested in dealing with even extremely particular issues. Such an art wants to be a partner for politics and science, not an ornament — it doesn’t want to be but a decoration for the privileged class’s everyday life. The schism has already taken place — a split in art took place somewhere around 1968. That’s when all those tough, absolute avant-garde languages emerged — languages that radically transform art into a germ of a social movement. And art remains today in such germinal form — it can develop into a decoration, or into social, political activism, into a cognitive activity similar to anthropology, or into a social movement. I think the latter scenario would be most interesting. The various isms were precisely attempts to transform art into a social movement. And art on many occasions put itself at the disposal of social movements, such as socialist realism, or post-WWI pacifism — that’s what Cubism or Dadaism were.

Halina Nowina-Konopczyna and Witold Tomczak, right-wing deputies, lifted the stone weighing the pope figure down in the Cattelan sculpture. They acted for ideological reasons, believing the pope figure needed to be “rescued.” It’s interesting how the hard right, which they represented, always at odds with art, learned the strategy of happening and used it. Those people can be our opponents in the game of art, in the game of arguments that art joins by means of images. Generally speaking, that action means that politics reads art and is starting to use it. In a way, those people joined the game — transformed a work of art in the gallery — treated it as an argument in a debate and responded with their own argument. Another move should have come from Maurizio Cattelan. Unfortunately, art proved unprepared for such a debate — everything ended with a media scandal and accusations of vandalism.

VS: Characters who have been important in your career (Andrzej Munk, Marek Edelman, Tadeusz Borowski) are some of the main postwar protagonists of the cultural scene in Poland. I have the feeling that countries such as those of Eastern Europe inherited practices of art that deal with political issues as well as their history. This attitude could be explained as the expression of a social duty, but also as a cathartic process. What are your thoughts on this?

AŻ: I think that in the consumerist democracy people experience catharsis by spending money at the shopping center. The freedom of artistic action is an excess in a democracy in which the individual is molded into a consumer by the united forces of advertising and politics. Advertising is present-day propaganda at politics’ service. Art is on the front line, providing capitalism with its know-how, that is, how to use images in a persuasive manner.

Marek Edelman is one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. I like an anecdote he tells, and which is more than just a wartime story. He and his unit were stuck at some building, the doors and staircases had been barricaded, they were on the second floor. To get them, the Germans had to drill holes in the walls to insert explosives and blow up the whole building. Edelman and his men couldn’t leave the building because it was daytime, they had to wait until dusk, and the Germans kept drilling the holes for the dynamite. There was nothing to do, so Edelman and his men went to sleep. Polish history is always so hectic, so neurotic, there isn’t a moment without fighting in it. In Edelman’s history, there is fighting, but there’s also boredom, sometimes there’s nothing to do. So Edelman and Munk were guys who believed, but only as much as was necessary — and they were never attracted towards sacrifice. I like this kind of calmness and skepticism. It’s a similar case with Borowski, whom the Auschwitz experience taught to stay clear of heroism and sacrifice. In Poland, you always had to do more, much more, because it seemed that otherwise the country would be lost, and that unless a hecatomb took place, there’d be no freedom later. Edelman criticized the murderous economy by saying that you stage an uprising when there’s hope of winning, or when there’s no hope at all, but you don’t risk the lives of the 250,000 people who died in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

The treatment of Eastern Europeans and Jews during WWII, as Borowski wrote as early as the ’50s, was colonial, typical for the methods of colonial expansion. It was Europe’s garbage dump and that’s why the Jews were brought here to be exterminated — because, according to the logic of the Western European rational civilization, you dispose of garbage by taking it to the garbage dump. So if you ask me whether art here has inherited a political entanglement that can’t be separated from the region’s history, my answer is: it has. It has, because every action here used to be politically entangled — there was no break from politics here since at least 1830, the November Uprising. And, as a reservoir of activistic motivations, Poland can offer recipes on both entanglement and engagement.

VS: You once said that “Art is above all a reaction to problems in society, but it’s also an exploration.” What did you mean?

AŻ: Let me answer with a question: don’t we want to get rid of art? To free ourselves of it, to remove it? To clear the excess produced by it: of chaotic strategies, redundant, botched objects? Some part of art is a response to the issues of this society (or these societies), but the majority of it is but a production of absurd objects, idiotic languages. A small amount of meaning resting on an overproduction of meaninglessness. You can also say that art is a social issue in itself. It is, as someone said, an “open wound” in the social body. Perhaps responding to social issues carries the price of producing an excess of nonsense in art — as Grzegorz Kowalski calls it, “art pollution.”

Perhaps art is also a container for an excess of idiocy, for false languages. Perhaps its main goal is not to produce sensible objects, events, ideas and so on, but precisely to annihilate madness, lunacy, cruelty, political idiocy, by turning those into passive objects, into incomprehensible, and thus unthreatening, content.