Although it may be difficult or even unfair to make a true assessment of the real extent of Art & Language’s influence, whether with regard to the field of conceptual art, to the consequences that have resulted from its practice historically, or which continue to occur; or as a theoretical reflection on art criticism and analysis, and on its functionality in the contemporary world. Perhaps not enough time has passed, because these artists continue to conceive, discuss and write their ideas while simultaneously creating works of art and leaning on a natural pedagogical vocation to disseminate their reflections, actions and unique interpretation of art from the position of the actor as well as from the position of the viewer. And yet, without a doubt, we can definitely assess what Art & Language has meant and how it has evolved from its beginnings, as well as how it has interpreted art with regard to the relations linking the concept, language itself and artistic intent. Perhaps this unfinished reflection on their work forms part of the heritage of this group of artists and critics, writers and editors of a magazine that may well be more a journal of fundamental rules and reflections, a manifesto of intentions, than what we conventionally understand to be an art magazine; perhaps because the same magazine is already a work of art or, at the very least, a part of the artistic process. This attempt to break the boundaries of thought and artistic production has always been present in the intentions of these British and American artists. One piece of evidence for this argument is the final line of Sol LeWitt’s collaborative effort in the magazine’s inaugural issue, a collection of 35 sentences: “These sentences comment on art, but are not art.”

Volume 1, Number 1 of Art-Language: The Journal of Conceptual Art was edited in May 1969 by Michael Baldwin, David Bainbridge, Terry Atkinson and Harold Hurrell, who had already been working together for a while, for example in creating a number of conceptual art symbols, such as the Map of Itself (1967). Other collaborators on this first issue included Dan Graham, LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner, whom the founders felt represented some of the clearest stances of conceptual art on both sides of the Atlantic. In the second issue, Joseph Kosuth joined as an editor and the subtitle “The Journal of Conceptual Art” was eliminated forever. The Britons’ and Americans’ different understanding of conceptual art had more to do with the tautological position of the terms than with the practical activity of creating art; a clear example of this can be found in the second issue of 1972, in which Atkinson and Baldwin explain that they “don’t talk about predicates; [they] talk about general terms.” This differed from Kosuth’s position, who felt that he could to a certain extent accept ideological formulas to define a map of tautological messages, and thereby enrich the creation of information. Art & Language had always considered this desirable in any analytical process, whether critical or linked with the creative process. Some time after the group was founded, it was joined by the art critic and historian Charles Harrison and the artist Mel Ramsden, whose strong influence on its impact came precisely with regard to these two aspects. Nevertheless, Art & Language is a mutating creature: many people have contributed ideas to it, and in a certain way this continues today. To get an idea of the ‘creative corpus’ of which Art & Language has always consisted, more than fifty individuals participated in it (to a greater or lesser degree) between 1968 and 1982, with “the sad challenge of confronting the end of critical modernity,” as is written in The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain, 1966-1976. This clearly reflects a certain degree of apathy for the history of conceptual art and a cheeky desire for revenge that buoys an intellectual and ironic spirit even today.

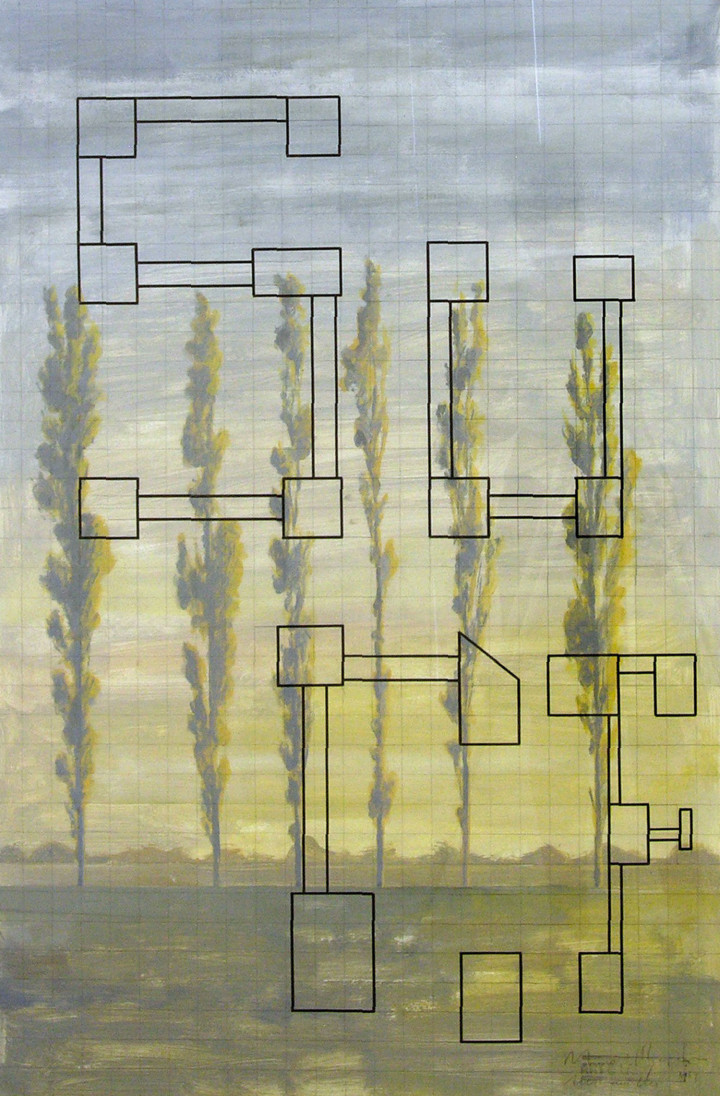

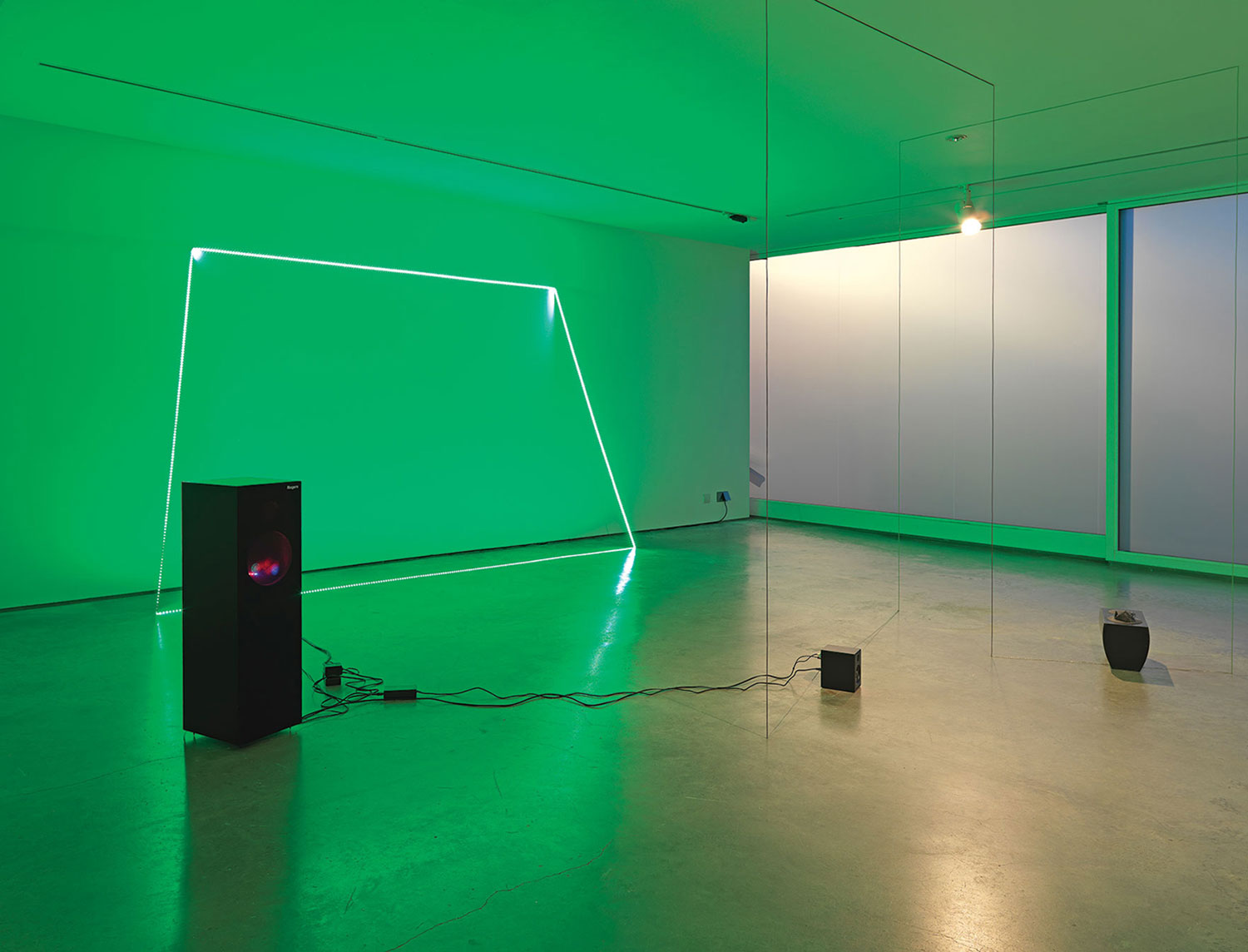

At first, the group was characterized by the reflection on and public dissemination of its principles and lines of thought through the magazine. Then, approximately between 1972 and 1976, Art & Language become linked with the magazine The Fox, and American editors enjoyed remarkable presence and influence. But by 1977, having shrunk to only the artists Baldwin and Ramsden and the art critic Harrison, the group began to view painting as an installation, and therefore as a vehicle for representing their reflections, since from the beginning Art & Language had never really stopped participating in the theoretical debate on the basic theses of artistic practice, modern art and criticism as a basic working objective, or as a crucial goal, even though from that moment on its members focused more on the specific issue of how the critical aspects affected them in the real practice of painting. In this respect, the group’s work has continued to build off these ideas and concerns that go on appearing indistinctly, whether in a magazine or in a gallery or museum setting, using the written word or painting, an object or an installation. And for this reason, Art & Language has broken with the usual boundary separating the artist from the writer. In other words, it has operated as the author of an artistic body of work based on words, such as with Harrison in the critical symposium “Art & Language in Practice,” held at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in 1999, and in the informal conversations that centered around Art & Language’s exhibition at CAC Málaga in 2004.

Even though the heritage that Art & Language has been accumulating takes many forms, not only in terms of conceptual art itself but undoubtedly also in terms of art history and criticism, the most fundamental elements of this heritage are its writings, the dissemination of its thoughts, the duality its members enjoy by being artists and writers at the same time — and by extension the feedback this produces within the artistic process, how this affects them, how they reflect on it and how these thoughts, in turn, can influence artistic practice once again. It is true what John Roberts wrote in “The Black Debt: Art & Language’s Writings” (2005), that the writing of artists has been a truly widespread practice since the end of the 19th century, but then it was almost always linked with intimate reflections on the studio, a kind of logbook in which the artist’s ideas and daily activities were told. However, among the avantguard of the early 20th century, the artist-writer had already turned into a strategic disseminator of his own work, a trendsetter, an expert in the use of writing as an industrial and commercial marketing campaign and a producer of declarations of opinion. This role was claimed and occupied by art criticism around mid-century, which partly negated the artist’s freedom to engage in criticism and theoretical expression with regard to art. At no point do these situations have anything to do with Art & Language’s position that it has always played a role of great public commitment and even acted as a provocative actor between the studio and the institution. Art & Language has leveled harsh criticism at many of its colleagues. It took its stern and ironic steamroller to artists such as Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, Mario Merz, Gilbert & George and James Lee Byars. It even tore to pieces the catalogue texts of artists like Carl Andre and Donald Judd. On minimalists, Art & Language wrote: “Now paintings make the works of the minimalists look like architectural details or simple, disturbingly obtuse works.” Art & Language understood that art could be a form of writing, and that writing constituted both art and itself at the same time. The relation between writing and art was not understood as a relational event, but as an intellectual process in which other contributions from sociology, philosophy and poetry should be accepted (an aspect broadly developed by Weiner as well, though unlike him, Art & Language’s ‘poetry’ was not lyrically minded but the result of an ability to harmonize in the text’s decoding process; its work was especially more poetic in the early years to the extent that it was able to concentrate on fewer idea-words), because the more cultured the writing was, the greater was its ability to generate images and produce art, which would become more systematized as well. There are also those who see a process linked with method in the collective’s manners of writing, practicing and thinking, but its approach is undoubtedly more free-thinking, more individualistic and therefore more linked to an intention to change art. The catalogue of the exhibition at CAC Málaga features a conversation among the three, then-current members of Art & Language in which Baldwin defines the entire grounds of debate for conceptual art when speaking of the options that Art & Language began to glimpse in the late ’60s: “It could lead to a kind of tentative practice that reflects on its own conditions and takes account of language and vocabulary, as well as of the historical nature of the gesture itself.” Needless to say, with this definition Art & Language limits its creative space, and its genuine legacy, in relation with another type of conceptual art that is closer to what is described as institutional theater — and which would take in the ideas raised by Beuys, Buren, Kabakov, etc. — with any current, continuous and generic product that can establish itself or distribute itself within the institution of the artistic circuit and with all that can, in the words of Ramsden, “be set up in the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern.” This option was advocated by art institutions from the late ’70s onward, and especially by curators, because it confirmed the need for their status, but also the need for the mass media because it made the contemporary issues of social and political debate its own, and it requires the public’s camaraderie, involvement, participation and interpretation to a certain extent.

Art & Language does not strive to recover a Greenbergian kind of modernity in its artistic practice, nor does it incorporate Greenberg’s concepts of independence and interiority. On the contrary, Art & Language’s creative processes share a lot in common with the pictorial process, because neither one requires, nor has ever required, an institutional and organic body of criticism or theory to justify itself. However, the degree of freedom that its independence grants it also makes it more insecure, because for a long time and due to many specific ‘sectoral’ interests, it has been argued that art could not be explained and defended with words, and therefore art criticism is vacuous. This undoubtedly limits the field of action, and not just for artists or collectives like Art & Language, which opted for the experimental alternative, a sphere that had previously been the preserve of art critics and the press, but also for those who opt for painting, because many painters feel they need to ‘invent’ a theoretical discourse subsequent to the pictorial process that legitimizes or confers authenticity to their work, thereby certainly distorting the original concept of the painting through the influence of an authoritarian imposition by the art institution. Thus, although Art & Language’s process is close to the painting process in terms of independence, it cannot be generalized openly because its process is based on conversation and debate, understood as a medium of exchange and production that is free of any type of selective hierarchy (although a certain selection of aesthetic aspects linked with the physical properties of objects is obvious), with the exception of minor ones found among conversation, writings, essays, annotations, sketches, papers, drawings, objects and paintings included in a publication or exhibited in an art institution.

In a certain way, Art & Language has felt it has had to invent a terminology that defines the artistic, theoretical and historical terrain in order to bring nuance to its reflections and stake its independence from the tensions and impositions of a hypothetical consensus in the art world: the nervous crisis of modernity to define generic conceptual art as a result of the historically specific movement of this type of art; institutional theater to refer to the aspects of conceptual art that are not based on reflective and theoretical discussion but on stage design; and the emergency conditional, which is without a doubt the term that best defines Art & Language’s stance on art and theory. This is a clever ploy to mislead, an exercise in escape, a scheme or what could even be called a magic trick. The result of Art & Language’s creative process is art just in case anyone thinks that it can only deal with theory, essay or critique, but it is also theory just in case it is identified as art. Therefore, Michael Baldwin, Mel Ramsden and Charles Harrison are artists just in case someone classifies them as theoreticians, and they are theoreticians just in case someone pigeonholes them with the name ‘artist.’ I remember a dinner conversation I once had with them at the Parador de Málaga Gibralfaro Hotel overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. We spoke pleasantly about these issues all night, and the conversation was like a circular loop that continuously sent us back each time a concept seemed too obvious. There was always a door open to nuance, to the philosophical relationship, to the unlimited continuity of the discussion itself, in which we all felt we were participating in a certain way, or at least most of us, and to the spirit and intentions of Art & Language. In a certain respect this is the only way it can be truly understood, this unique type of transitive creative process that is clearly subject to permanent revision, and is therefore always unfinished.