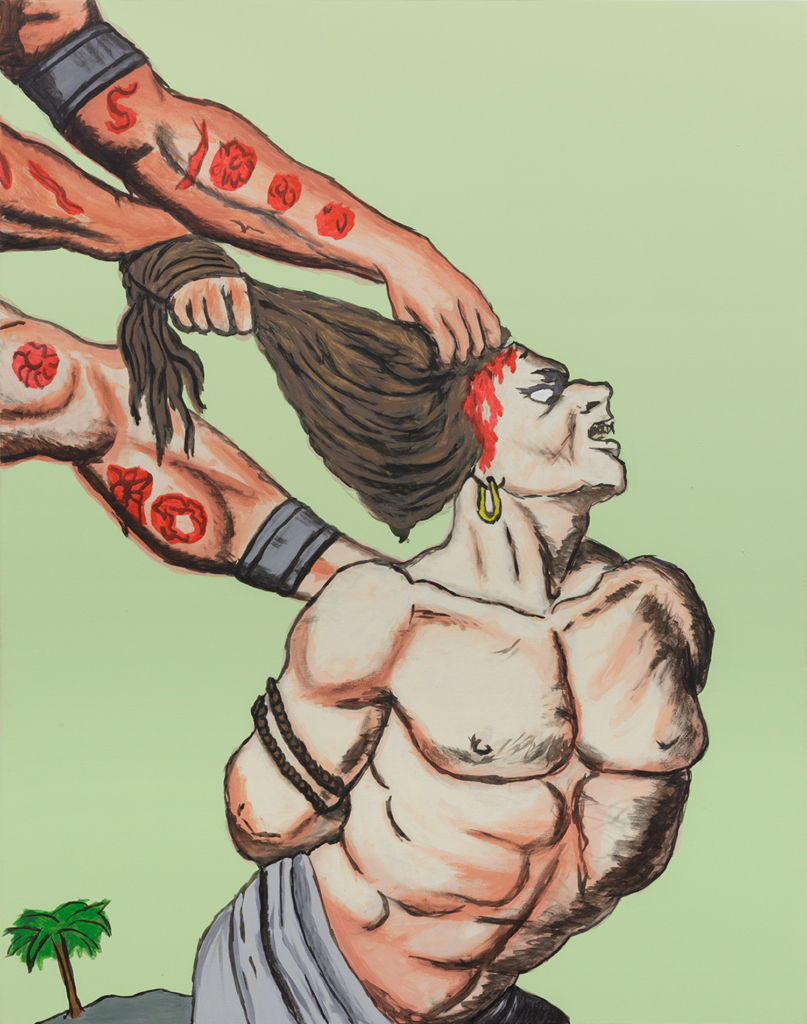

Antek Walczak advances the medium of painting as a kind of machine through which social, economic, political, and technological systems are ground down and assembled anew. Borrowing from the languages of communication networks, software engineering, and cybernetics, his work allegorizes the social, institutional, and economic networks that facilitate and regulate the production and reception of art, posing the question of how painting belongs to a network, but also how art itself is a system. Despite this inquiry into the logic of systems, Walczak seeks out and tugs at incongruous threads, resulting in a body of coexisting sentiments — sardonic yet sincere, aloof yet aware, brash yet introspective. However, Walczak, whose career dates to the mid-1990s, only came to painting within the past decade, having spent the previous sixteen years working predominantly as a member of the collective Bernadette Corporation.Since its formation in 1994, Bernadette Corporation has consistently eschewed painting in favor of a multifaceted approach to artmaking that encompasses fashion, photography, film, sculpture, installation, poetry, and publications. The group’s interest in the destabilization of individual artistic authorship, cross-pollination within the culture industry, and a politicized disruption of the networks in which art is expected to function have proven immensely influential. Though Bernadette Corporation has collaborated with an array of artists, Bernadette Van-Huy, John Kelsey, and Walczak were its principal members until the latter parted ways with the group in 2012. Walczak is assumed to have been heavily involved with the outfit’s published endeavors, such as its fashion magazine, Made in USA (1999–2001). During this same period Walczak produced a number of self-authored videos, suggesting the possibility that he was responsible for the filming and editing of Bernadette Corporation’s lauded video works, such as The BC Corporate Story (1997), Hell Frozen Over (2000), and Get Rid of Yourself (2003), though it is of course impossible to determine exactly who did what.

All this is to say that with such a comprehensive history of working outside painting, it is rather surprising that Walczak’s solo practice, since departing Bernadette Corporation, has been almost exclusively committed to the medium. In order to properly unpack Walczak’s work of the past decade, it would appear necessary to first interpret this turn to painting after a sustained period of abstention. Certain contemporaries of Walczak who are similarly interested in financial systems and social networks — Simon Denny and Katja Novitskova immediately spring to mind — shun painting in favor of appropriating the corporate aesthetics native to their subjects of critique. Walczak addressed his distaste for such overt emulation when in 2015 he offered, “By simply making art that is not a painting, seventy-five percent of concept is already delivered on the plate as gesture and statement. Add to that any kind of out-of-art-world factor like a social science or two, some agriculture, animal husbandry, or gene splicing, and your art concept hits the ground running.”2 While apparently shedding light on his reasons for exiting a collective that never engaged painting, Walczak also stressed the Sisyphean challenge to painting’s vitality. As everyone knows, painting requires a conceptual remapping within its own parameters, yet it also frequently “finds itself most fully only where it is most deeply in question.”3

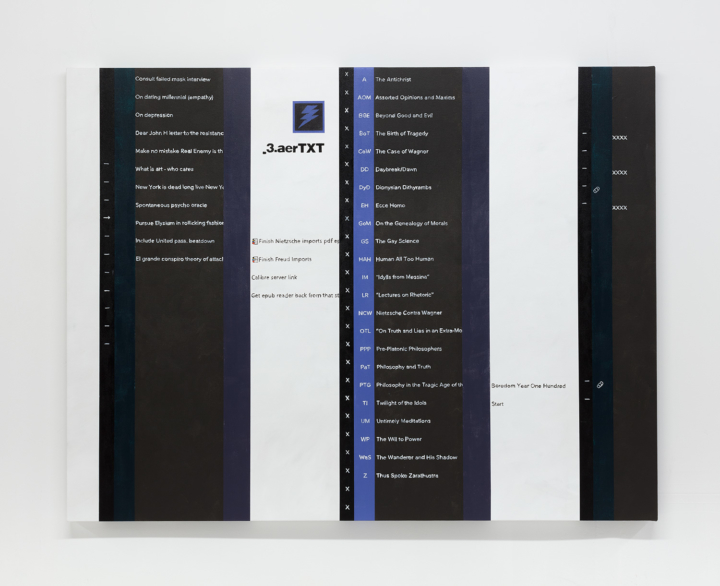

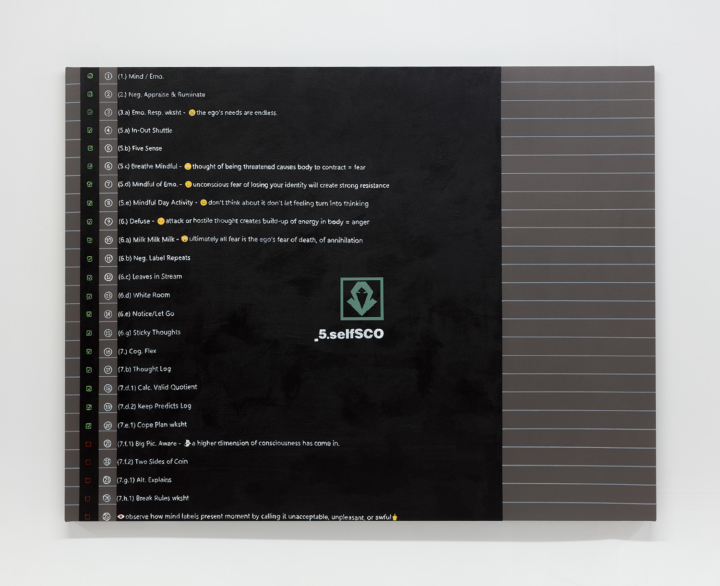

Both of these ideas were clearly in mind when Walczak embarked upon his 2010 solo exhibition “Empire State of Machine Mind,” the artist’s first determined foray into painting. Housed at Real Fine Arts in Brooklyn, the exhibition consisted of four large white canvases on top of which appeared black letters, darting arrows, and not a few distended ovals. Resembling a game-play diagram gone haywire, the compositions were in fact lyrics plucked from Jay-Z’s 2009 hit “Empire State of Mind” spelled out using the Lempel-Ziv-Welch data compression algorithm. The resulting compositions appeared as though they had been screen-printed but were in fact traditionally brushed with acrylic. A premeditated index of physical labor, this trace of the hand could come off as a gambit intended to increase value, but ultimately functions as a synapse between machinic and haptic fronts — where the rigidity of a digital network meets a pliable body. More to the point, Jay-Z’s hymn to New York City’s fabled capacity for social and economic transcendence provided the perfect conduit for Walczak to model how painting acts as a vessel for the social and intellectual networks that undergird its production — the compression of the social context of the New York art world into what David Joselit and Isabelle Graw have referred to as “the networked painted object.” In the end it’s all about who you know. Success that stems from networking is one thing, but making art about this activity is quite another. Other painters, such as Jana Euler and Mathieu Malouf, use the material constructs of painting to stress the social imperatives of the art world. But whereas Euler and Malouf point out the existence of such a network, Walczak foregrounds the conditions of participating within it. Indeed, he takes up the baggage of “networked” painting to hold up an antagonistic mirror to it, calling to mind the shortcomings and problems inherent to such an exercise — including his own complicity in doing just the same.

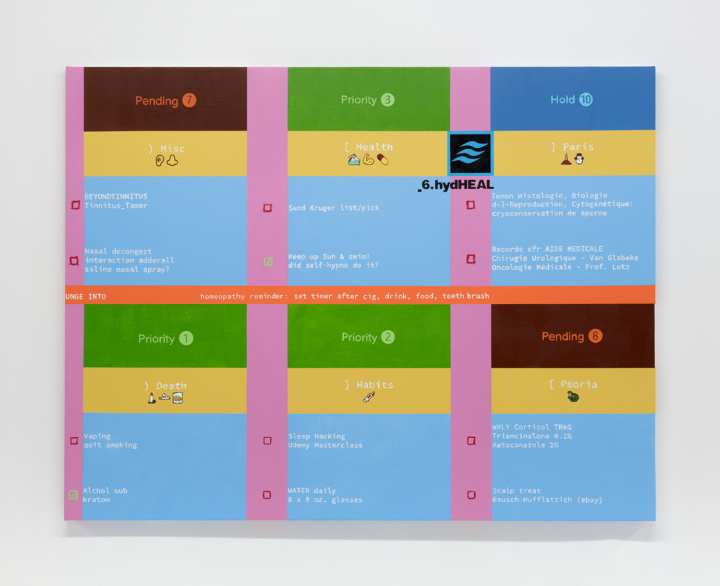

For obvious reasons, many artists avoid acknowledging in their work the clandestine mechanisms of wealth, its influence and the validation it imparts in contemporary art. Whereas certain artists call attention to the networked nature of the art world to broadcast their success, Walczak frequently wields his art to foreground the frustration and exhaustion of maintaining currency within such fickle webs. The artist’s 2013 solo exhibition, “New Transbohemian States,” again at Real Fine Arts, found him ensnaring himself within these matters more overtly than ever before. The series took the form of monochromatically grounded, uniformly sized square paintings of state-transition diagrams, a type of blueprint frequently used in software engineering. In Walczak’s paintings, these each took the shape of a familiar Disney or Warner Bros. cartoon character — Mickey Mouse, Woody Woodpecker, et al. Tightly installed along just two of the gallery’s four walls, their colors flickered against one another like a structuralist film. The connect-the-dot-like diagrams of numbers and arrows have a single word inserted between each number so that they blossom into full sentences. They also offer a choose-your-own-adventure kind of reading. For example, in Greed (2013), whose composition takes the form of Donald Duck, number one can go in any of three directions: sequentially linking to two, forming the phrase “I want to be a contemporary artist”; splitting off to three, which leads the viewer to “I want all integrity by being the critical artist”; or jumping to ten to come up with “what constitutes my institutional value.” Effectively these texts forge a road map of the artist’s simultaneous compulsion to operate within and vexation toward the system of art, pushing the conflicting stances of self-implication, sincerity, and mockery to a cathartic edge, revealing their author by turns competitive, revelatory, smug, trite, and downtrodden.

If these consecutive Real Fine Arts shows were diagrammatic pantomimes of the trials and tribulations of the networked artist, Walczak’s subsequent shows, “The Lead Years” (2012) and “Kompromat” (2017) at Mexico City’s House of Gaga, displaced such introspection in favor of highlighting the currency of metal. “The Lead Years” was comprised of eight lead panels onto which spam emails were silk-screened. New Order fans will immediately link their visual language to the cover art of the group’s 1986 album Brotherhood (one of the works shares that very title). These variously sized and formatted texts were culled from Walczak’s junk mail from 2007–08, covering the period before and after the beginning of the global financial crisis. All are in the service of phishing schemes in the guise of investment opportunities, brandishing statements such as “Gold investors find a safe haven as the US dollar continues to drop throughout 2007” (Storm, 2012), and peppered with baiting phrases like “Don’t miss it” (Saturn, 2012) or “just click on the icon below this text” (Titanic, 2012). These spammed texts come to us in the form of painting situated on the poisonous substrate of lead, suggesting the “toxic” nature of art and technological systems alike. Indeed, Walczak’s panels, again acting as agents for concepts and realities outside the art object, suggest that the content of the spam text is less important than what it says about content circulation and financial systems as well as our parallel dependence upon and wariness of technology. Much in the same manner as the “Machine Mind” and “New Transbohemian” paintings, these works were serially installed ruminations on a single theme, varying little in terms of individual composition yet acting as a durational sequence that forged formal relationships and linguistic meaning within the movement from one end to the other, evoking the cinematic technique of montage. In fact, Walczak’s use of montage in the context of painting reveals the clearest correlations with his former, filmic practice, suggesting that painting, for him, is perhaps a finite enterprise — a planned obsolescence. In addition to underscoring our terrifyingly vulnerable position in relation to technological and economic circumstances beyond our control, “The Lead Years” saw Walczak dabbling in astrological significations. As he wrote in the press release, the “alchemical symbol for lead is the same as for the planet Saturn.”4 If in 2012 Walczak metaphorically raised the value of lead to that of gold under the foreboding presence of Saturn, he foretold his confrontation with “Venus, mother of Libra, whose symbol denotes copper.”5

Accordingly, Walczak fulfilled this fate by staging “Kompromat” at the same venue five years later. Although the exhibition was not exclusively dedicated to copper, the side of Venus that speaks “of our self worth, money, banks” was nevertheless manifest in three paintings executed on copper substrates.6 Atop their shimmering surfaces Walczak silkscreened images of hundred-dollar bills with transparent ink and then corroded the surfaces with various chemicals and exposure to the sun, inescapably calling to mind both Andy Warhol’s early “Dollar Bill” and late “Oxidation” paintings. While the titan of twentieth-century Pop was undeniably obsessed with cold hard cash, Walczak conjures the notion that art, like money, benefits from circulation, particularly in our age of electronic exchange and crypto currencies.

As we have seen in his canvas, lead, and copper works, Walczak clearly exploits painting as a means of working through technological systems, social networks, and the omnipresent forces of capitalism. Yet he also appears distrustful of painting’s ability to properly channel these ideas outside the realm of art. To this end, Walczak seems less interested in theoretically parlaying painting’s limits than utilizing the medium both allegorically and ironically: allegorical in that he is using an existing medium to address matters external to it; ironic in the acknowledgement of its self-imposed “impossibility.”

It is perhaps with these thoughts in mind that in early 2016 Walczak mounted an exhibition of non-painted, professionally produced works at Dominique Lévy in New York. These hexagonally shaped dye sublimation prints on metal were installed in groups of three, resembling chemical formulas or honeycombs. Each computer-generated composition is populated with gaming icons (rooks, knights, hearts, clubs, swords, dice, “eject button” arrows, etc.) that coexist on a segmented monochromatic plane, creating visually differentiated but conceptually linked constellations. The layouts were designed utilizing a digital mosaic-patterning technique that allows random content population within any given field, resulting in splayed and overlapping imagery recalling early video games.

Later that year Walczak produced a second iteration of the series at Jenny’s in Los Angeles titled “Neanderthal Interface Guidelines.” This was comprised of thirty-six works installed on a single wall in a tessellated rhythm. As before, these works also made use of digital shorthand language (signs, glyphs, and symbols). Their use here is emblematic of the continuing evaporation of written language in favor of a universal, egalitarian approach to the sign. Prolonged viewing of the segmented hexagonal formats allows the viewer to perceive two different compositional geometries and to vacillate between them: a flattened hexagon and a cube. The former makes for immediate legibility of the two-dimensional glyphs, while the latter allows the flat figures to float in imaginary three-dimensional space. Toggling between the two produces a kind of gestalt image that makes for enthralling viewing. Unlike the East Coast manifestation of the series, the pattern of symbols here are printed across multiple panels, making the thirty-six-part installation in effect a single, undulating artwork, flowing from deep blue at the upper left (Ocean, all works 2016) to a mustard yellow at the lower right (Crater). The titles allude to natural phenomena (Fjord; Delta) or specific geographic locations (Dasht-e Lut; Sibillini Mountains), mirroring the way tech repeatedly evokes nature, such as Mac’s successive operating systems — Yosemite, El Capitan, Sierra, and Mojave. Though the press release for “Neanderthal Interface Guidelines” repeats the artist’s apparent frustrations with uncritical “trending” artistic production, it also drives home that Walczak is creating a legible critique — a caustic screenshot — of those very propensities. For ultimately systemic critique is at the very heart of Walczak’s work — that is, until he renders it obsolete.