In 1970, the American architecture and video collective Ant Farm advertised their distinctly countercultural services as “air buildings, nomadic visions” in the “unclassifieds” section of Domebook One, a do-it-yourself dome-building manual. On the facing page was an image of a fifty-by-fifty-foot pillow they were experimenting with for a planned event called the Mt. Fuji Rock Festival.1 As with Ant Farm’s earlier one-hundred-by-one-hundred-foot inflatable, this pillow was conceived as a key piece of environmental equipment with which Ant Farm could test out the rapid deployment possibilities of a dispersed “instant” urbanism premised on “the evolving lifestyle associated with the rock festival.”2 Although the event did not go ahead, this pillow would have another life as a prop for ecology and alternative architecture events, put to work during their “Demonstration Tour” in spring 1970, and would in turn come to be conceived as one component of a wider technical infrastructure that might serve as a technology of survival for new climate extremes. The notion of global warming per se was not yet present in environmental activism circa 1970. Yet I return to Ant Farm’s media-savvy deployment of inflatables as tools to raise environmental awareness as a reminder that images matter, that they can operate to shift conceptual and material dispositions regarding the environment. At least in the right hands….

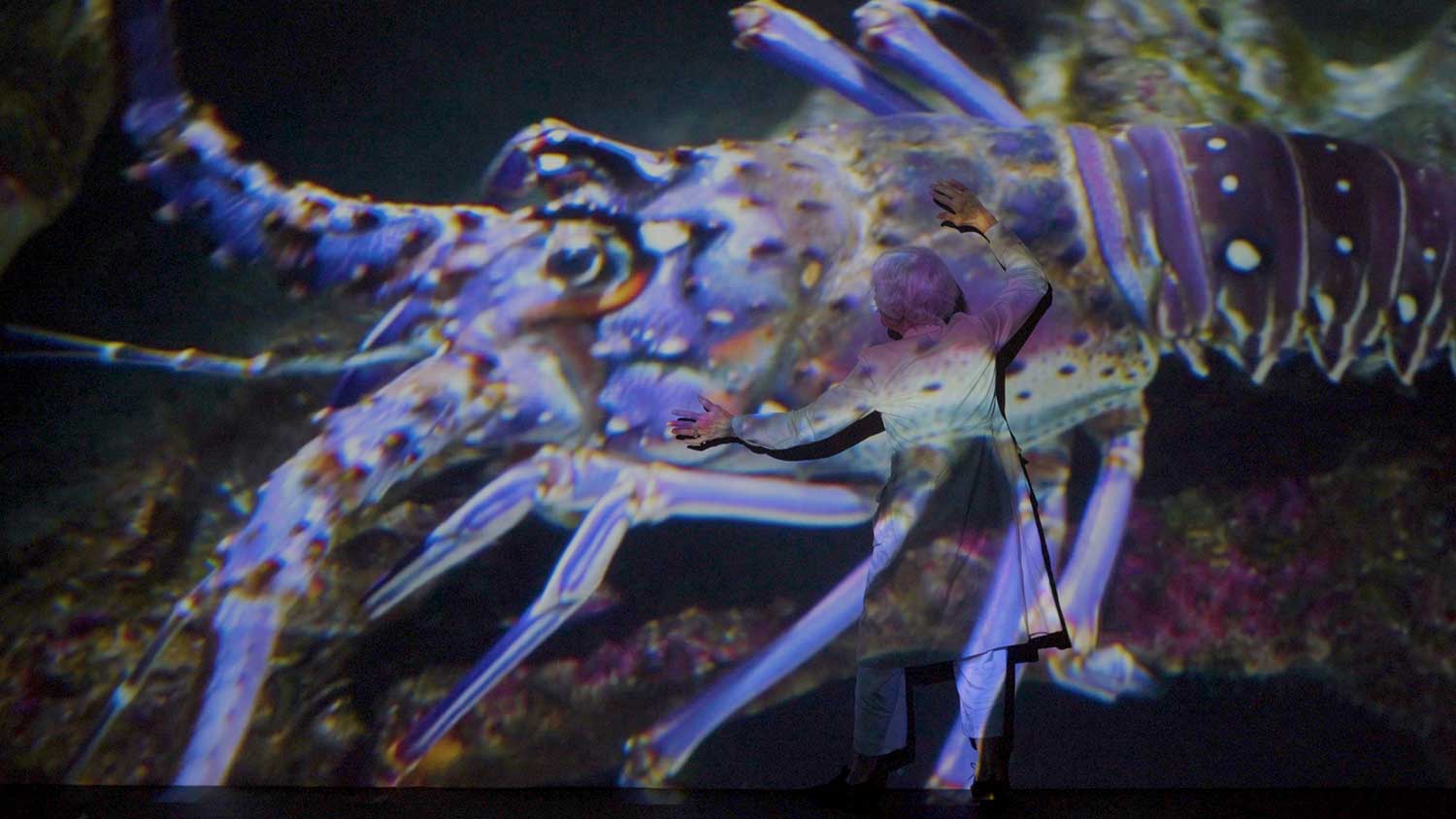

Ant Farm’s spring 1970 “traveling show of inflatable structures and environmental information circus”3 included an Earth People’s Park ecology event and the Air Emergency performance for Earth Day at the University of California, Berkeley, both in April. Dressed in lab coats and gas masks, and with the pillow referred to as the Clean Air Pod (or CAP 1500), Ant Farm staged Air Emergency as a savvy piece of “media theater,” “pollution art,” or “life art” that wryly captured the escalating sense of the destruction and militarization of the environment. A result of having studied the civil defense graphics and fallout shelters of the 1950s, Air Emergency was a “survival event” in which those who didn’t seek shelter from pollution by entering CAP 1500 were told that they would die within fifteen minutes from an “air failure.” Small yellow circles were attached to “victims” remaining outside, who were informed that the circles were “sensors which can be monitored by a Human Resources Satellite which is tracking your final movements.”4 Ant Farm had become an Office of Air Emergency Mobilization, a broadcast service dedicated not simply to escalating the rhetoric of impending doom but to taking their brand of “eco-tripping” back to the media.

The group also attended the International Design Conference in Aspen in June as part of a countercultural contingent that radically destabilized the identity of this long-standing modernist institution. IDCA 70 adopted the title “Environment by Design,” but its commitment to ecological concerns remained for many younger participants inscribed not only within the ideological limits of an outdated institution and its conception of environmental activism, but confined within an equally outdated presentation format that precluded interaction and feedback. A documentary film by Eli Noyes and Claudia Weill made this evident: cutting back and forth between the multiple camps, the film reveals the disjunction or “generation gap” to be all but unbridgeable, despite attempts to bridge it through the official inclusion of environmental groups and a “black caucus” as well as via counter-attempts to infiltrate the conference’s main tent with theatricalized hippie culture.5

Ant Farm’s mode of presentation, by contrast, repeatedly sought to push the limits of existing formats. “Categorized as lectures, ecology events, environmental alternative displays, or art,” the group explained, “Ant Farm projects are, in reality, always treated as response information exchanges.”6 Many of Ant Farm’s events with inflatables, including that at the rock festival Altamont, were recorded in Pneumad Popstars (1969/70), a mesmerizing 16mm film shot by Kelley Gloger, which gives some sense not only of the fluid and amorphous environment the early inflatables gave rise to, but of the wonderment and almost ecstatic pleasure they elicited from people participating in these unscripted performances.7

(Industrial) Production in the Desert

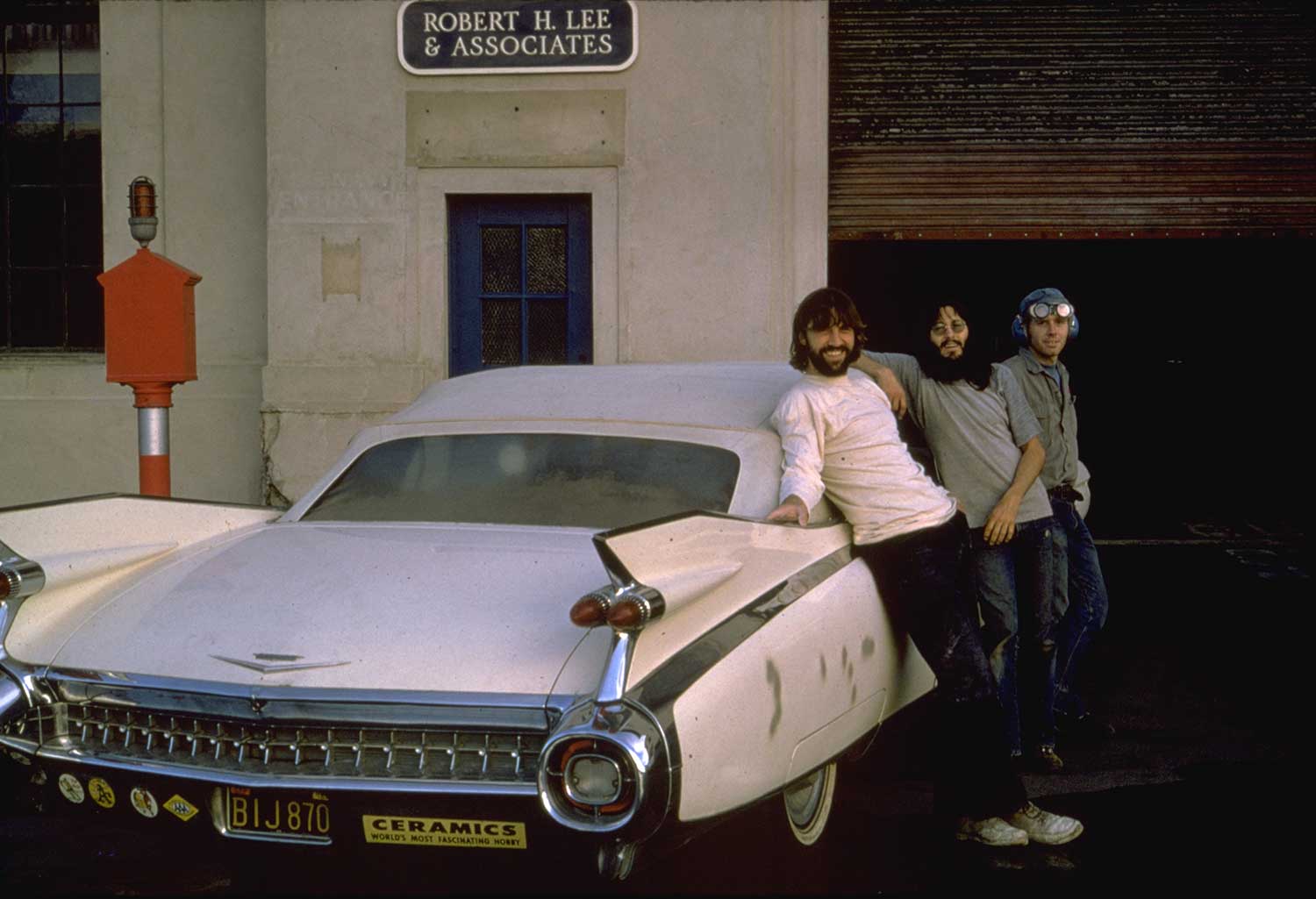

Toward the end of their experimentation with pillow-shaped inflatables, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog Stewart Brand commissioned Ant Farm to provide a mobile facility for the production of an edition of the Whole Earth Catalog Supplement. Armed with portable equipment — a fifty-by-fifty-foot inflatable, two geodesic domes, an Airstream trailer, IBM Selectric Composer, Polaroid MP-3 Camera, and a massive fifteen-kilowatt generator — the production team, along with Ant Farm members Doug Hall, Andy Shapiro, and Curtis Schreier, headed to the Saline desert, west of Death Valley, where winter temperatures rise to 106 degrees — an extreme environment imagined to be on the horizon of possibility. “Production in the Desert,” an account of the event and its experimental infrastructure, appeared in the January 1971 Whole Earth Catalog. Its epigraph read, “Workers of the world, disperse.”8 Like geodesic domes, the inflatable participated not only in an architectural or urban fantasy but also in a social, environmental, and geopolitical one. The success of the Whole Earth Catalog had arisen in part from a countercultural dispersal or exodus from the city, a continuation of what Leo Marx identified as a long-standing anti-urban, and distinctly American, “pastoral impulse.”9 Picking up on the growing search for alternative lifestyles, the publication had fueled do-it-yourself ideals of access to tools and information and other strategies for withdrawing from normative lifestyles and capitalist modes of consumption and waste. In the comfortable setting of Menlo Park, Brand founded the Catalog venture in 1968 as an entrepreneurial service for that dispersed (whole earth– and ecology-identified) community as well as for “weekend drop-outs” desiring to be part of it.10

Ant Farm produced their own, distinctly more ironic, DIY manual soon after, launching the Inflatocookbook in 1971. In reviewing Inflatocookbook, Robert Greenway noted that Ant Farm’s “nomadicry” offered the “presumption” of an “aesthetic environment to go with their work towards a surviving environment.” He also pointed to what seemed to him a contradiction. “True, inflatables are liberating,” he conceded, “but they are also desperately hooked to the umbilicale [sic] cord which is connected to Con-Edison, etc.”11 Life off the grid was understood by many to be the only real means of escape from what was widely referred to as “the system.” But while it remained “hooked up,” Ant Farm’s work was not seamlessly integrated into that system. If avowedly charmed by figures like R. Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan — both of whom ultimately maintained an uncritical relation to the technical infrastructure of the mainstream administrative and political system — Ant Farm would come to articulate a different type of relation to what Eisenhower famously designated the military-industrial complex. Although attempting to operate with high-end technologies, their work departed from the unquestioning naturalization of technology characteristic of Fuller and McLuhan. Ant Farm identified with the countercultural ethos of dropping out, and searched for an architecture and environment appropriate to this form of refusal. Yet their practice would remain not only “on the grid” (even if entirely sympathetic to solar energy) but very much engaged with new technologies — not to reinforce the emergent techniques of power to which technological inventions would in part give rise under the auspices of their economic and military potentials (think surveillance and tracking, rapid deployment units, and the expanding use of petrochemical products as new materials for everything from fertilizers to weapons), but in order to understand their very manner of operation and to forge prospects for alternative uses of that same technology.

In the desert, Ant Farm inflated their fifty-by-fifty-foot clear vinyl pillow and placed another lightly inflated, slightly translucent pillow on top, hoping to control air temperatures inside. Designs for this “double pillow” appear in Schreier’s notebook T13, along with detailed calculations for his PVC dome that served as a darkroom.12 To avoid uplift, the pneumatic structure was anchored to the ground by a massive net made of eight-thousand-pound strapping, with 3/8-inch chain attached to “dead men” — large logs buried several feet beneath the ground. Despite these precautions, the attempt to tie the structure down failed after a few weeks, when a cable snapped from the tension caused by high winds — another environmental hazard familiar from extreme climates. Production activities quickly migrated into the campers, domes, and Airstream trailers, and the pace of the work on the publication picked up.13 Insulation problems in the inflatable — stifling heat when the sun was out, freezing as soon as a cloud came by — led one member of the Supplement team to hang “heat lamps from the ceiling which ascended and descended with variation in pillow pressure,” almost burning the vinyl base in an act of self-immolation as the structure periodically deflated.

That Ant Farm’s project for the Whole Earth Catalog was understood as a departure from the constraints of architecture and its normative institutional or disciplinary function was noted in “Production in the Desert.” “Naturally,” Brand announced, “we imagine ourselves helping to liberate other publications, schools, projects, all you wall-bound souls.” But his response was not entirely positive. “My love-hate relationship with inflatables is in full bloom here,” he went on. “They’re trippy, cheap, light, imaginative space, not architecture at all.” To which he added: “They’re terrible to work in. The blazing redundant surfaces disorient. One wallows in space.”14 This wallowing and fluid sense of disorientation was, of course, central to the psychedelic aesthetic logic of the work. As Ant Farm explained in Inflatocookbook:

In case you hadn’t figured out a reason or excuse, why to build inflatables becomes obvious as soon as you get people inside. The freedom and instability of an environment where the walls are constantly becoming the ceilings and the ceiling the floor and the door is rolling around the ceiling somewhere releases a lot of energy that is usually confined by the xyz planes of the normal box-room. The new-dimensional space becomes more or less whatever people decide it is — a temple, a funhouse, a suffocation torture device, a pleasure dome.15

Cast as a decoupling of relations between form and program, inflatables produced an environment all but hostile to conventional use, and one that, as Brand lamented, rendered climate palpable. This was an architecture hoping to overcome not only traditional semantic and formal associations but, to reiterate, normative social and institutional relations. Environmentally, Brand had concluded, perhaps ultimately missing the point, “What an inflatable is best at is protecting you from gentle rain, not a problem here.”16

If the disorienting, interactive pneumatic structure was difficult to produce a print catalog in, it had other useful qualities, as Ant Farm (like Brand) understood very well. Opening with a photograph of the glowing, transparent plastic pillow set against a massive mountain range in the California desert, and ending with an image of the site returned to its pristine condition a few weeks later, the article in the Whole Earth Catalog offered seductive images of the inflatable environment and the distinctly ludic sensibility it seemed to elicit. The use of products of the petrochemical industry would soon come increasingly under question, both for their toxic effects on people and the environment and for their role in the US-led war in Vietnam. But the image of an emancipated environmental condition facilitated by inflatables and captured in photographs involved at the time a carefully crafted and powerful visual rhetoric, especially when broadcast through the media. The event was in fact not simply recorded in print media; Brand himself made a Super-8 film depicting the sense of mobility and of intensive group interaction or collaboration that went into not only the catalog but also the work (and play) environment.17

Intermedia

That Ant Farm understood inflatables less as a form of shelter than as one channel in a multimedia environment or event was repeatedly indicated in Inflatocookbook. The section dedicated to color and materials addressed the issue of using projected light: “Frosted poly is best for rear projection, white for front projection.” Inflatocookbook included, furthermore, events like Air Emergency and Globe City Today, the latter a one-night show at the Sausalito Art Center. In the center of the gallery space was a thirty-foot weather balloon “with a long tube entrance and squeeze-through hot lips at either end,” along with another inflatable inside of which was a waterbed. To these were added not only quivering mirrors known as “Garden of Delights” and a gyrating kinetic art piece called “Electric Love,” but also a “video network picture phone” described as “a dynamite invisible environment between the inside [of the balloon] and the outside.”[18] Likewise, along with designs for inflatables and systems such as an air-supply deck, we find in Schreier’s notebooks detailed designs for media equipment such as the AMMO-KLIP Projector Slide Feed. Ant Farm’s expanded conception of architecture was evident again in their presentation of the World’s Largest Snake, a project submitted to Design Quarterly’s “Conceptual Architecture” issue. Complete with a Media Van plug-in, “ultra-sonic media blasts,” and programmed areas such as oil massage, cloud, and “snake rattle & roll room,” the vinyl-tex-skinned snake inflatable, as the disjointed accompanying text read, “eats videoscreens [and] a 5 man crew, explores limits, blows up buildings, destroy Fat City, build real©ity. Solar energy, dreams, enviroyesterday, mobile tomorrow.”[19]

But perhaps more important to the direction of Ant Farm’s work even than these multichannel performances with inflatables are three other, if distinctly interconnected and collaborative, trajectories that also appear in the final pages of Inflatocookbook: Truckstop Network, the Media Van, and the turn to video as another medium for research into and potential broadcast about the environment — or perhaps more properly put, the expanded conception of what environment might mean in an electronic age.