Andro wekua’s work combines a seductive and terrifying sense of composition, which seems to be walking in its sleep, with a will to present introspection in a way that is both disturbing and precise. The sculpture called Wie heisst Du mein Kind? (What are you called my child?, 2004) shows a well-dressed boy made of wax with his face smeared with a great mark, like cake. As though untouched by this humiliation, the boy is standing upright, defiant and stoical on a tall black plinth. He has wooden wedges under his shoes to prevent him from falling over. Wave Face (2005) shows a pale young woman sitting upright in a black armchair. She is holding a black clay mask in her right hand, in which she is reflected, and in which she is immersing herself. Like the boy, she has been mounted on a massive plinth, a fragile stage made up of dark ceramic tiles, which gives the scene a heroic and dramatic feel. Get Out of My Room (2006) and Wait to Wait (2006) take this form of advanced contemplation even further. In the former, an older boy is sitting indifferently in a room, with his feet on the table and his pictures on the wall. In Wait to Wait he is sitting with his face blackened, crouched over himself, motionless and impassive in a box-like greenhouse behind green, blue and orange panes. The prison-like showcase stands in a room with his own images hanging on the walls, so that if he were to look up he would see only himself.

These installations are set up so that viewers are invited in and excluded at the same time. As in the theater, they are involved in every detail from the outside, lured in and at the same time kept at a distance. They do not know what is happening backstage. Before us we see figures abandoning themselves to retrospection unconditionally, believing that self-absorption protects them from the world, that the outside world cannot harm them because their rich innermost thoughts offer everything they need. The perfect interplay of color, material and composition with which Wekua stages this state of affairs reflects the irresistible attraction of introspection. All this is not to be had without some terror, derived from the knowledge that being absolutely at one with one’s self is to be achieved only at the cost of losing the world, loneliness and the disintegration of the self. That is the story of Narcissus and his ruin.

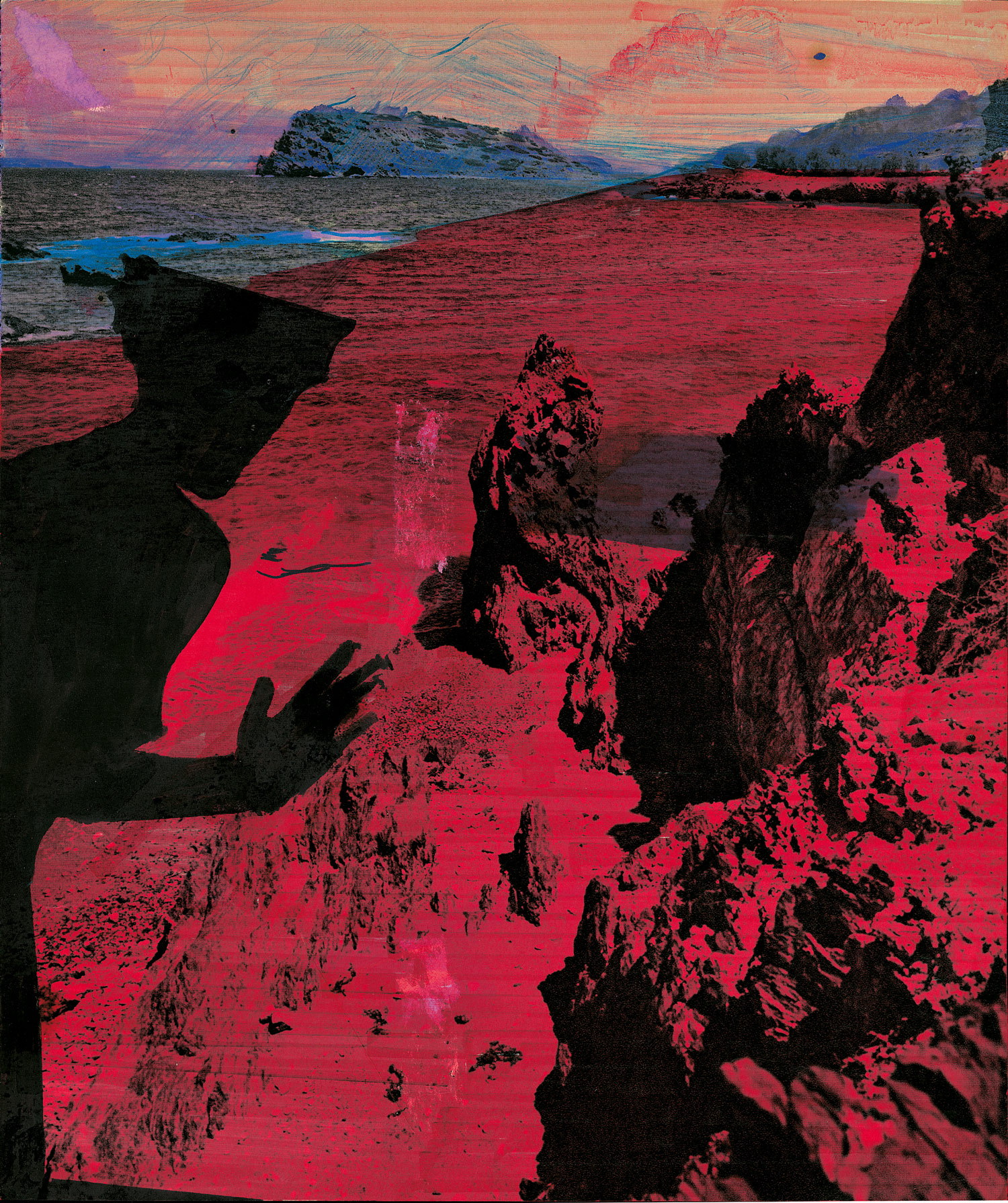

But introspection is more than self-love. It is memory, which can lead to melancholy, turn into obsession, or also heal. Andro Wekua’s drawings, collages, prints and paintings are to be understood as memory images of proud individuals, immersed in themselves. They require the utmost in concentration and in intensity; they are at the same time home and anything but homey. Like other artists of his generation, Andro Wekua is going back to the vocabulary of the classical avant-garde. But abstraction, Surrealism and Bauhaus are not used with a view to a social utopia and emancipation, but privatized, which has resulted in these artists being reproached with romanticizing and aestheticizing. But this overlooks the fact that they consciously accept this ambivalence, that they see it as fundamental and do not feel that it is up to them to resolve this conflict for us. In this way they can be both skeptical and affirmative, because they have replaced the idealized notions of an ‘original’ avant-garde with a mediatized and stylized image. This took shape in film and photography as early as the 1920s, and still determines our understanding of the avant-garde and modernism to a considerable extent. They are harking back to a dandified avant-garde in order to be able to use distance to acquire emotional drama and radicality, artificiality and truth, abstraction and narration. Here it can be that this high awareness of history and the way it is presented can turn into introspection and lead to estrangement. Then we are faced with the kind of cultural narcissism as embodied in words like Mannerism.

It is no secret that any memory, however personal, however distant, is steeped in the present: it is not formulated in the language of the past, but uses the language of the present. Andro Wekua employs formal avant-garde achievements of the kind that are now accepted everywhere in order to construct his images of introspection — achievements of the kind that the avant-garde itself stylized, and that still fuel people’s yearning for the avant-garde. This means that Wekua shapes the object of memory with a language that is itself already rich in memory, that acknowledges itself as artificial and passé. Just as the figures reflect about themselves, memory is also mirrored in itself. That is the temptation, the promise and the terror in Wekua’s pictures.