London waits for an Andreas Gursky exhibition and then two come along at once. This spring twelve new works by the German photographer are on display: nine hanging in Jay Jopling’s monolithic White Cube in Mason’s Yard, with the remaining three forming an inaugural show at Sprüth Magers’s new gallery on Grafton Street.

Gursky’s latest pin-sharp wide-shots explore his now-familiar thematic dichotomies of macro and micro; individual and mass; photographic documentation and abstract formalism.

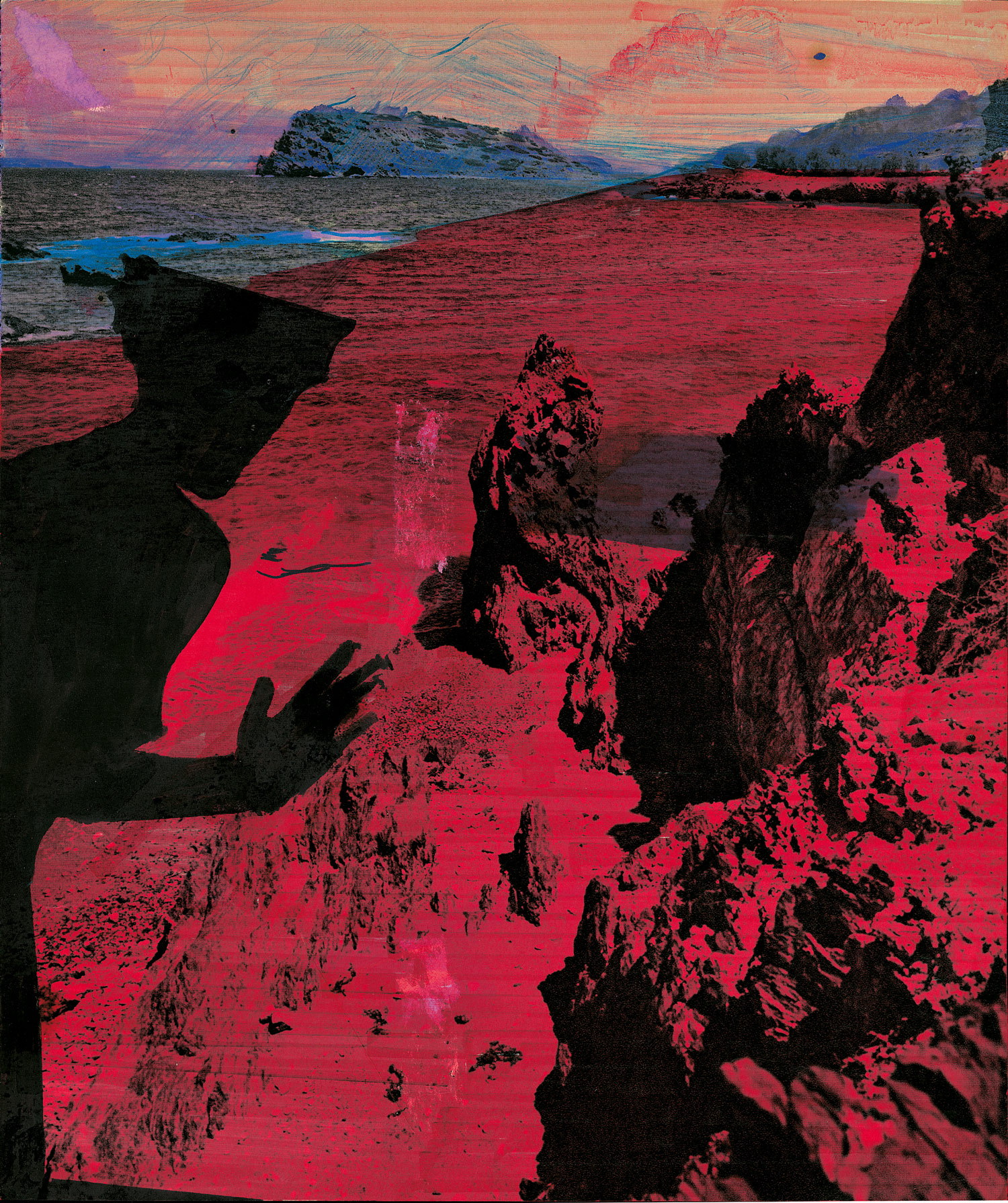

Brazil, France, Germany, Monaco, Turkey, Bahrain, China, Japan — Gursky has scoured the planet for spectacular sites and the resulting images are as arresting as anything in his oeuvre. Japan’s Super-K underground water tank appears in Kamiokande as a dazzling gold sci-fi cavern; two small boats reveal its mind-bending scale. In Bahrain I and II, tarmac zig-zags across desert sand, creating contemporary near-abstractions reminiscent of painters Frank Nitsche and Dirk Skreber. But perhaps Gursky’s most intriguing geographic venture is to the ‘outpost of tyranny’ in George W. Bush’s “axis of evil”: North Korea.

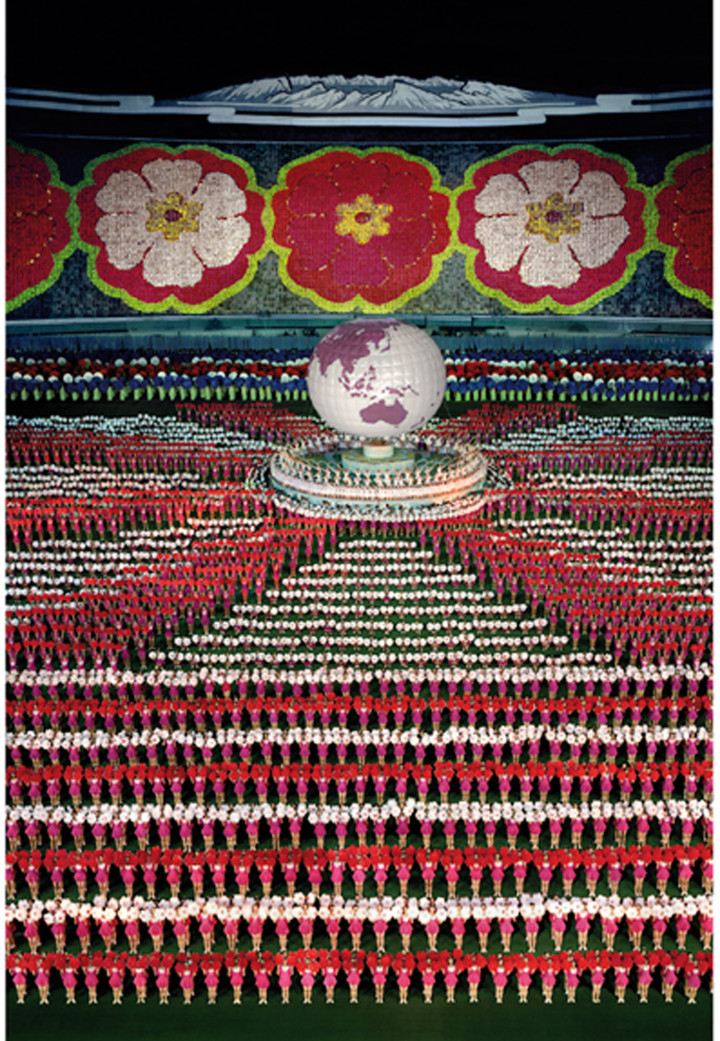

Despite recently agreeing to disable its nuclear facilities, North Korea remains synonymous with secretive political (mis)conduct, excessive militarism, widespread poverty and a damning human-rights record. It is also known for its celebrations of the late communist leader Kim Il-sung in the Arirang Festival ‘mass games’— stadium performances involving 50,000 gymnasts and soldiers, backdropped by an equal number of schoolchildren holding colored panels in the air to form an enormous human video wall. Each child is a well-rehearsed pixel.

Gursky has photographed the Arirang Festival in a series titled “Pyongyang,” becoming appropriator and documenter of a self-contained performance, and this changes everything. Previously his images of humanity have revealed how we are unconsciously formed by certain patterns and collective activities. Arirang short-circuits this because the participants know that they are performing a spectacle of mass configuration; the only difference is that Gursky explores the representation of scale, while Arirang performs scale itself. Nothing is revealed by photographing Arirang from a high vantage point, because the performance is directed toward the same bird’s-eye view that Gursky pictures it from. Nor does his medium capture what is most compelling about the event — its movement.

But this is not to say that the “Pyongyang” pictures fail. They may be among Gursky’s most interesting photographs, precisely because of the push-pull between author and subject matter. Two models of artistic practice are present in the work: Arirang epitomizing communist culture with its kitsch militarism and emphasis on group dynamics over individual prowess; and Gursky emerging as the individualistic artist under capitalism, single-handedly authoring his vision and submitting it to the market.

Thus it seems apt that the “Pyongyang” photographs show people facing the camera. How would Gursky’s art appear to them? Would it be loaded with dubious cultural associations, as their ‘mass games’ are for us? In charting the culture of our increasingly global society, Gursky raises such questions, relativizing the role of his own work in the world that he depicts.