To the art world connoisseur, the name André Cadere is largely associated with conceptual art, although he does not rank among its foremost representatives.

This partial lack of recognition is arguably due to Cadere’s persistence in pleading for the integrity of the art object in a period when the work of art was subject to fierce negation. He regarded himself as marginal, a condition he identified with as an émigré coming to the Western world from a communist country, but also as an artist who engaged critically with the boundaries of the art system, refusing to let himself be absorbed by its mechanism.

Cadere’s current reception and the critical writings on his work have taken into consideration the period after his arrival in France, in 1967. Moreover, with very few exceptions, the discussion is largely focused on his activity following the apparition of the Round Bar of Wood in 1972, the object that would render the artist famous internationally. Almost nothing is mentioned of his early period in Romania, as if his personal and artistic narrative had started with the moment of his ‘escape’ to the West. This situation was no doubt generated to a certain extent by the artist himself, as he seldom referred to his Romanian background. The effort of grasping Cadere’s artistic endeavor and personality should take into account his tendency to veil the traces of his former existence and replace it with the newly acquired identity. That is why art critic and historian Jean Pierre Criqui’s comment on the artist’s inclination to control the assessment of his own work seems accurate: “It is obvious that the only work to which Cadere wished to lay full personal claim was done during the period when he conceived his round bar of wood.”1 On the other hand, on at least one occasion Cadere invoked his Eastern origin and termed it a “determination” that better prepared him to face the initial rejection of the art world.2 His self-proclaimed marginality in the Western world was in fact nothing new for André Cadere, for back in his home country he was exemplarily trained for practicing marginality, albeit one of a different kind. As the son of a former diplomat who after the instauration of the communist regime went to prison, Cadere could not pursue an artistic education at the Fine Arts University in Bucharest and did not have access to the state-controlled art galleries.

Despite these difficult circumstances, Cadere was part of an artistic milieu, which included both established artists as well as self-taught ones.3 In their attempt to surpass the dogmas of socialist realism, they turned their attention to abstraction and experimented with a plethora of styles that ranged from surrealism to op art. Cadere showed an early interest in the theory of color4 and took part in underground exhibitions, demonstrating the ability of making visible his paintings in an unfriendly environment.

On the other side of the iron curtain, Cadere experienced another kind of power, that of the art galleries and museums. What sets him apart from other artists commonly associated with institutional critique is that his strategy — and, consequently, the visibility of his work — was neither replaced by theoretical statements nor restricted to a specific place, but rested on the assumption that in order to prove its efficacy the practice should be enacted “each day.”5 Hence, the crucial importance of the concept of mobility that represents the core of his artistic strategy and which allowed him to “question the power of the gallery,”6 striving to achieve independence and autonomy with respect to the art institutions. His daily, solitary and at times repetitive walks (he undertook identical urban promenades at different moments in time),7 always carrying the rounded wooden bar, liberated him from the confines of the gallery space. This nomadic condition also enabled him to test the modes of functioning of the art world — its discourses, practices, people and events —, ceaselessly mapping its territory in order to grasp the state of his own art. As he succinctly put it, “My art is the situation of my work in the art world.”8

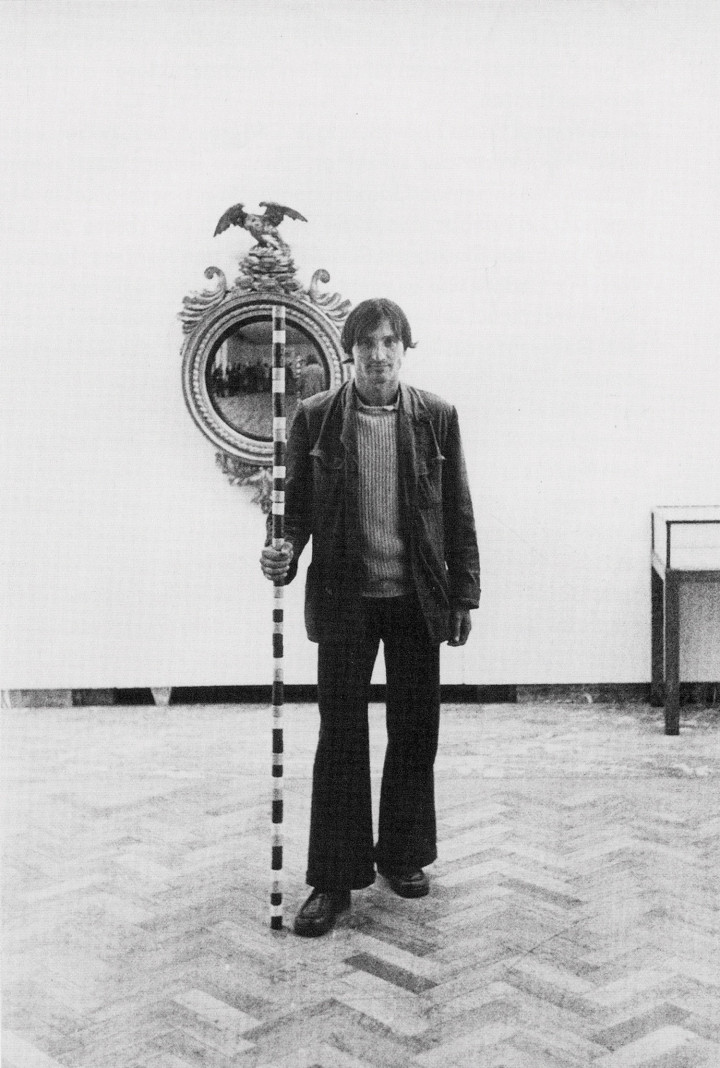

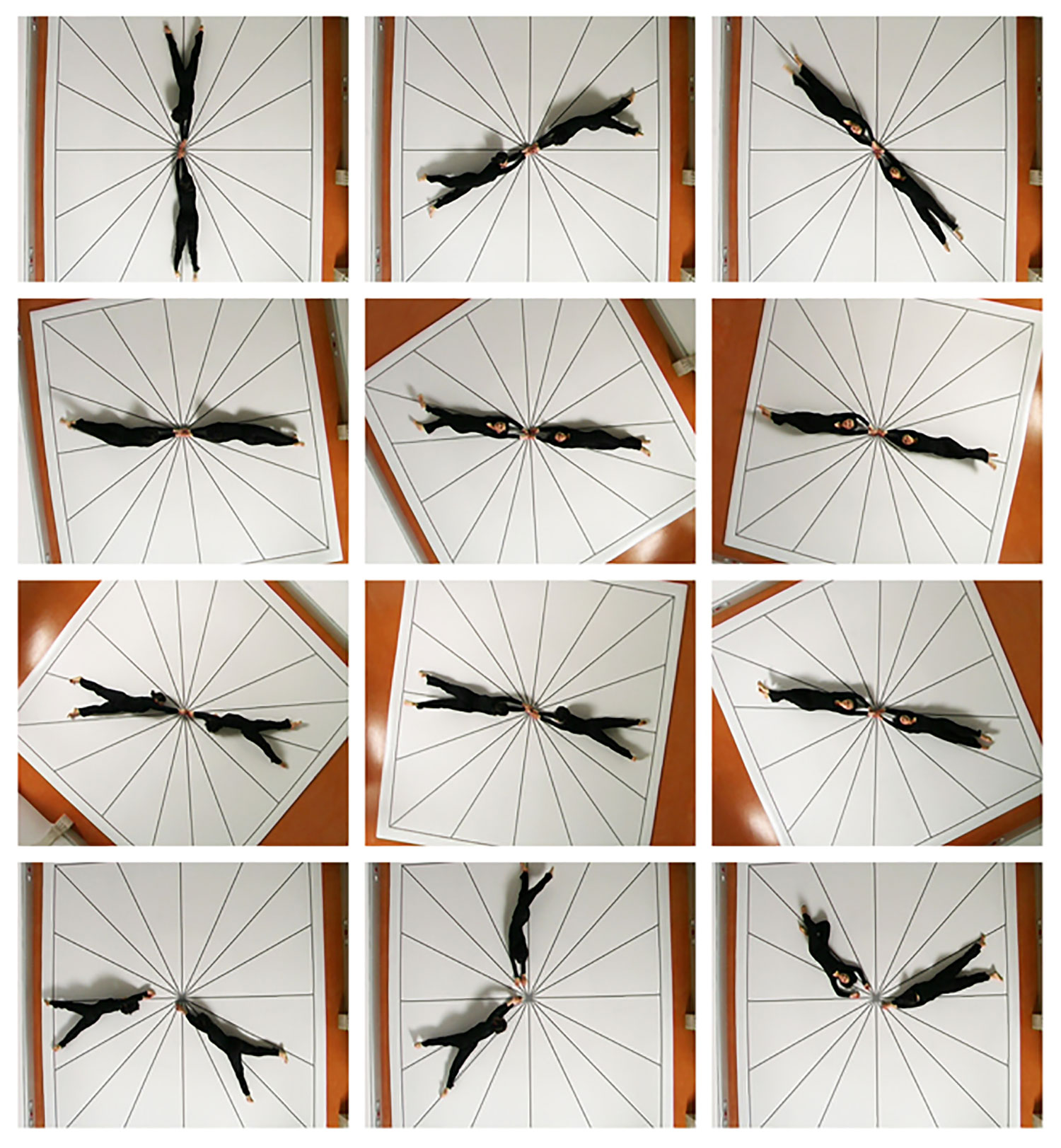

This strategy of movement is understandably not devoid of contradictions. Cadere was well aware that, even though he acted outside the world of the galleries or the museum, he was essentially caught in a dialectics of inside and outside, in a situation of “unstable equilibrium”9 as he named it, which nevertheless provided him with the sole possibility of articulating a critical position towards the art system. The way he chose to challenge the physical space of the gallery was different from that of Daniel Buren (the two artists were involved in professional controversies more than once), in that Cadere was not keen to engage with the specificities of a given site. It was not the architectural determination of a particular institution — that an artist like Buren sought to expose and challenge in Peinture-Sculpture (Painting-Sculpture), his famously censored installation for the Guggenheim Museum in 197110 — that triggered Cadere’s polemical appetite. Nor did he commit himself to an investigation of the unscrupulous alliance of art and capitalism, as Hans Haacke had done successfully. Furthermore, Cadere distanced himself from the phenomenological perception of the exhibition space as advocated by Minimalism, while at the same time criticized the idealistic perfection of its fabricated objects, devoid of all error. His work is undeniably conceptual in the sense that he used a set of pre-established rules to fabricate his wooden bars, which he designated as paintings, and issued certificates to authenticate and sell the pieces. Even if crafted by the artist (and displaying this hand-made character), the making of the bars relied on a system of mathematical permutations that implied a carefully calculated interplay of color and error at the level of the cylindrical segments that made up each piece. The bar was an instrument that instantly signaled its primary function, that of being looked at. The bar could stand anywhere the artist wished to, in any imaginable form of display, conspicuously absent from exhibitions in which Cadere was invited to show it, or irritatingly present during events that did not welcome his participation. The artist shrewdly played with the procedures that regulated the activity of a gallery, staging unofficial ambulatory ‘exhibitions’ that ran parallel with the official programming, mocking the protocols of time and space assigned for conventional exhibitions. “My work does not have anything to do with the architecture, with the style, with the aesthetics of the gallery, but it does have something to do with ‘what a gallery is.’ A gallery is a structure of power. My work has a critical attitude against that power. […] This is what I call the political in my work.”11

The refusal to relinquish his independence and assumed marginality was made manifest, for example, on the occasion of a group exhibition at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels in 1974. Invited to show together with Marcel Broodthaers, Robert Ryman and Dan von Severen, Cadere preferred instead to exhibit only during the opening, wandering around with his bar as in the days when he was a complete outsider.

Attentive reading of Cadere’s letters to Yvon Lambert,12 written before his premature death, suggests that the artist paid increasing attention to the possibility of developing series and constellations composed of large numbers of bars, thus counterbalancing the critical and at times iconoclastic stance of his work with a more ‘classic’ mode of display.

One wonders what direction his work would have taken had he had the time to explore and exhaust the formal and logical possibilities of the mathematical method he devised to perfection. Would he have downplayed the performative character of his work?13 Yet, Cadere’s intentions are not easily predictable, because with him one should always consider the intrusion of error, apt to disrupt the inflexible order of things. Even at the end of his life, he deemed it necessary to stress the importance of his own presence in connection with an exhibition he was planning at the Barry Barker Gallery in London. Unable to go there, he sent instead three photographs to be exhibited in the gallery, showing his “actual situation”:14 him on the sidewalk outside of the hospital with the wooden bar in hand.