Anat Ebgi: Your installation at Herengracht 401, Claustrophobic, involved the belongings of Claus Victor Bock, a German Jew who hid at this location during WWII and returned later in life to reside. The room had been untouched since Bock’s death in 2008. How did you approach your role of interpreting the text and capturing an aura by confronting a Jewish man’s hiding place and subsequent home?

Amie Dicke: I felt that it (the aura) must lie somewhere between the various objects, pieces of furniture, carpets and the hundreds of books in the house. I wanted to make a cover that touched every surface of the interior. When I understood that the room that belonged to Claus Victor Bock was going to be moved and thus changed to let someone new live there, I felt it was the right place to trace. Then I started to learn more about Claus. He wrote a book about his life during the war and hiding at Herengracht 401. This helped to get to know him, but mostly I feel like I got to know him through his belongings. When you spend hours in someone else’s house without them there you are still a guest and it took me some time to become at ease. I had to touch the objects and books, but often felt like he could walk in and catch me being curious (or snoopy.)

AE: The idea of haunting permeates this project and there is a gothic motif that is evident throughout your practice. What is your attraction to the dark side?

AD: The knowledge that things will decay, fall apart, lose their shine and that their colors will fade is what makes them so beautiful, but at the same time it frustrates me. Destruction is the dark side, but at the same time it creates a place for the new. The brutality of randomness is embedded in nature: “The banality of evil.”

AE: How does this project correlate to your previous work that focuses more on fashion, femininity, and your own personal identity?

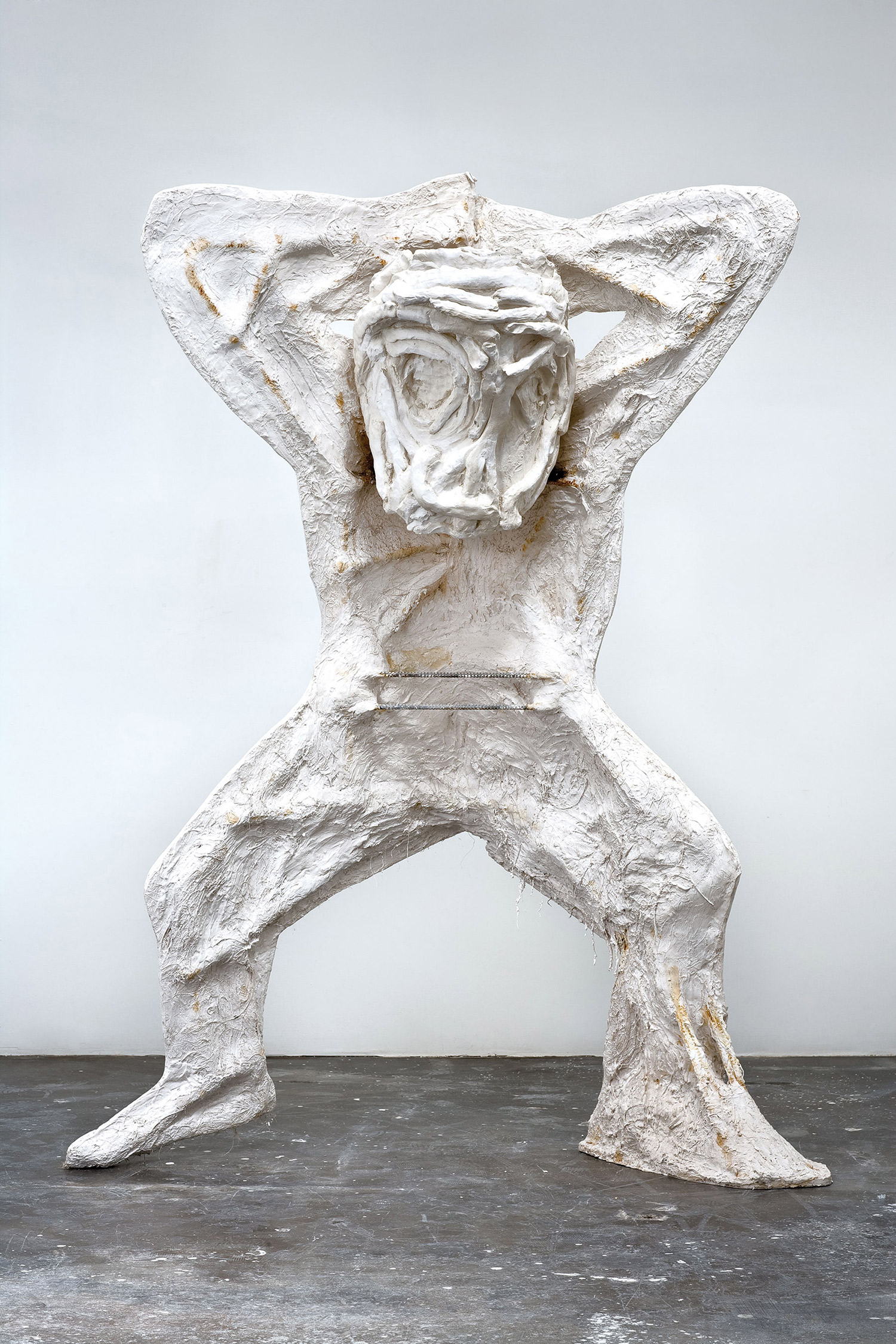

AD: The question of ownership is an apparent theme. Working on Claustrophobic reminded me of the works I made for the exhibition “Private Property” at Peres Projects in 2006 where I tried to confront my own furniture by taping it in black masking tape. The black tape stands for a combination of censorship and protection, keeping the objects (my personal furniture) and the attached memories private. Protection can be very suffocating. This must have been the case also for Claus while hiding. The ‘void’ and ‘emptiness’ are recurring themes, especially if compared to the cutouts, but everything in Bock’s room was the opposite of fashion and femininity — perhaps that is why I was so attracted. The invisible is very important in this project, which reminds me of the “space between my legs” sculptures made of sugar and marzipan. The soft substance echoed the negative curves of my body. An echo is exactly how I would describe the plastic room.