Ali Banisadr wakes up pretty early, goes for a run in Central Park, comes home, answers e-mails, reads the newspaper, catches up on research, writes down his ideas then goes to the studio. When he is in the studio he enters a new dimension that is based on the dialogue between him and the painting. He tries to really listen to what the painting is asking for. Once the relationship begins, time disappears. And if this occurs, it means he had a successful day in the studio.

Ali Banisadr likes poetry. This is not a coincidence. Beside the obvious connection between his work’s musical and lyrical tone, there is a deeper subtext regarding the artist’s attempt to question language. Among all written forms, poetry probably has the strongest potential to surpass its intended function. The artist does the same with the language of painting, of which he has great mastery. Once the initial observation of the painting is surpassed, a new kind of comprehension comes in, clarifying — paradoxically — how what we are looking at is an example of something that tried to convey a meaning and at the same time tried to refuse it. “It happened and it never did” — exactly like the title of one of his shows.

Ali Banisadr paints a combination of his own memories and Persian mythology. For example: Marco Polo’s discredited story of the Hashshashin, a militaristic sect whose members were drugged and made to believe that the gardens behind their mountaintop fortress were actually heaven, where obedience might be rewarded by short visits, replete with feasting and vestal virgins. Influenced by Persian miniatures — small, intricately rendered illustrations similar to illuminated manuscripts — Banisadr’s canvas unfurls like an ancient map, a spatially skewed terrain of detailed activity. Throughout, angular shapes suggesting topsy-turvy architecture provoke a disorienting sense of wonder. Out-of-scale figures are formed from indulgent dabs, and exotic fauna and pools evolve from luscious smears and layered washes. Rendered in the gold and blue associated with European religious painting, Banisadr bathes his scene of earthly pleasures in a divine glow, ignited by bombardments in the distance.

Ali Banisadr has always had this urge to combine everything together, to be able to concentrate everything in one place and have it somehow make sense. This is something that has been present since he was a little kid. He often feels overwhelmed by all the things that are going on in his head, and the work becomes his way of putting them on a surface and trying to understand them. That being said, the way he works has now reached a stage where it begins to communicate more comprehensively. In 2006 he began to make charcoal drawings based on the sounds of explosions, thus bringing auditory elements into the work and letting his subconscious take over. After this, he started to compose his paintings in an auditory way, which felt very organic and visceral.

Ali Banisadr often goes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where, coincidentally, his work is on view among his favorite artists. He calls the Museum his second home. There, he is able to dig into art history and find different things based on what he needs at the time, from Persian to Mughal miniature paintings, from Egyptian sculptures to Japanese prints, from European Renaissance paintings to cinema, from the visual experience of Claude Monet to the obsessive brushstroke of Vincent van Gogh. However, the artists who have influenced him the most are Willem de Kooning, Diego Velázquez, Gerhard Richter, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hieronymus Bosch and Tintoretto.

Ali Banisadr conceives most of his works with the lack of a center. Scattered, diffuse, dispersed, the characters animating his large-scale paintings are continuously undermining the necessity of a focus. For him, seeing and non-seeing are connected both to motion and to the imaginings of the mind. In his imagination, things are always in a state of flux, and so the resulting images are based on fragments from different places, which are combined until they become encyclopedic hybrids. Unlike many of his contemporaries who conform to traditional Western painting conventions, Banisadr refutes the idea that a painting needs a central focus. He wants the entire painting to be the focus; every part should matter. He also wants to capture non-static elements like sound, to turn what he hears emanating from his landscapes into something visual. Often these elements emerge as ghost-like figures. Banisadr draws inspiration from the meticulous paintings of northern European artists. Although these western sources are important, equally significant for him are Persian miniatures of the 15th and 16th centuries — especially in terms of how he builds up the ground of his painting and deals with space. He has an acute awareness of the role of the invisible.

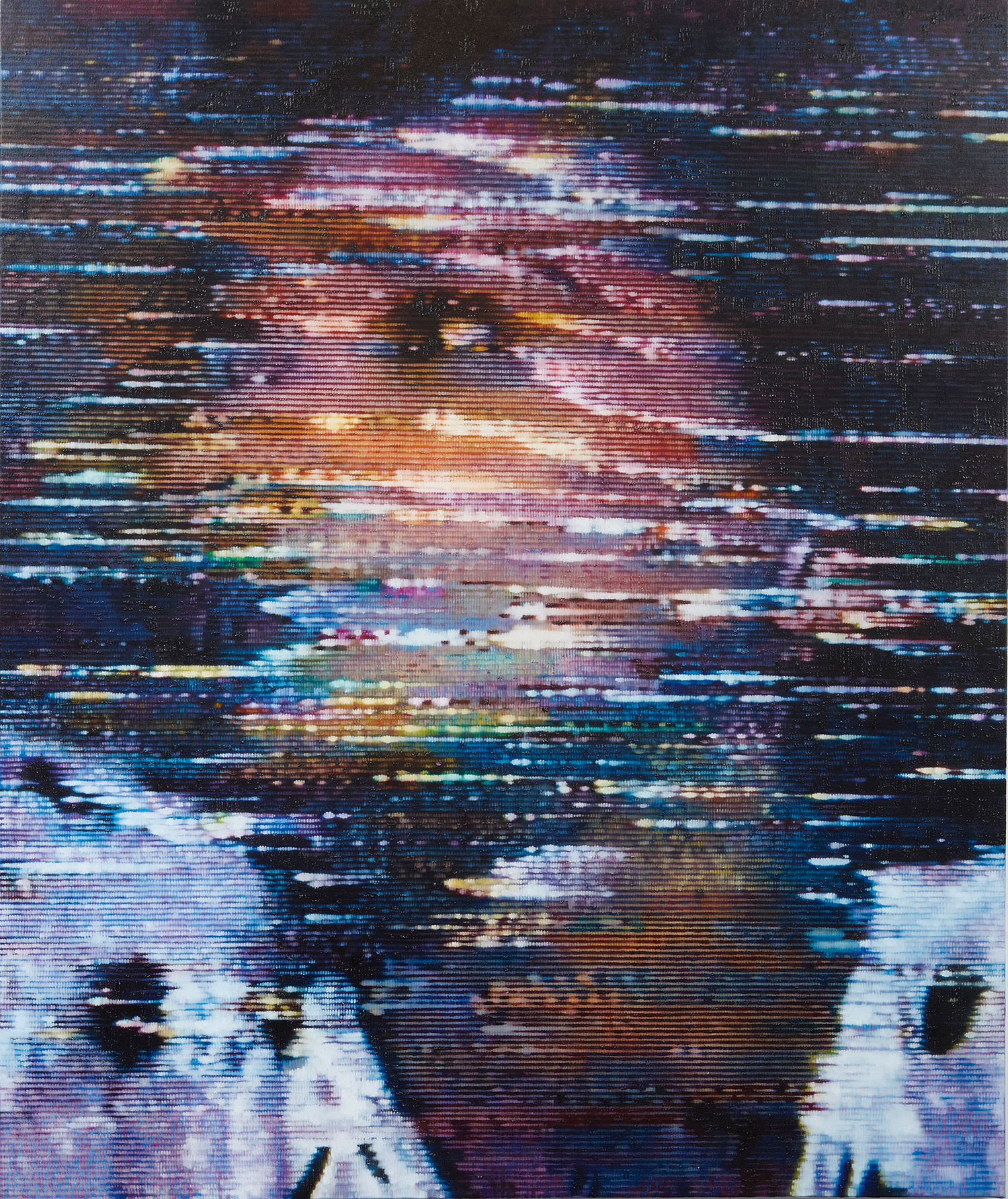

Ali Banisadr agrees that photographing his work is very challenging. When you look at it in reproduction you may think that it is an abstract painting, but once it is viewed in person you realize that there is a whole world in there that needs time to unveil itself. He has had many studio visits where people who did not know his work had a completely different idea of what the work was like until they saw it in person.

Ali Banisadr can be compared to Hieronymus Bosch. His portentous scenes are spellbinding in their finite description. From a distance, the intensely busy surfaces appear to be rendered in microcosmic detail, yet when viewed close up, recognition dissolves into a frenzy of sensitive and compacted brushwork. Banisadr handles paint with a sentient physicality; his extravagant textures and vibrant tones visually translate the experience of taste, smell and especially sonic fields of cacophonous rhythm. He thinks the comparison with Bosch is more about what Bosch was dealing with in his time. In other words, you can see the universal value in Bosch’s work, and you can still find the work’s message relevant today. Banisadr wants his work to function in a similar way.

Ali Banisadr keeps in his studio a Persian copy of The Adventures of Tin Tin, of which he has been a voracious reader since his childhood. He read the stories in Persian over and over again, and he could not get enough of the adventures that took Tin Tin to different parts of the world. He realized at a young age that, like Tin Tin, he too wanted to travel and see the world. He wanted to be always be searching for something, trying to solve a conspiracy. Tin Tin is still his hero, and traveling — whether it is physical travel or mental travel in the studio — is a very important part of his practice.

Ali Banisadr sees the narrative in his work as something developed out of painting. When he starts a dialogue with the painting, the figures begin to create a story of their own — they begin to speak to each other. His figures are archetypes; each represents many different things: a combination of personal history, art history and the history of our century. Banisadr likes when one thing can represent many things at once. Also, the narrative requires that the viewer participate in completing the story. The painting establishes a fifty/fifty relationship, asking viewers to use their own imagination to make sense of it, not unlike a Rorschach test. The artist is interested in seeing what the viewer sees in his paintings, regardless of whether the personal interpretation is close to the artist’s real intention.

Ali Banisadr comes originally from Tehran, but moved to America when he was a child; his works are influenced by his experiences as a refugee from the Iran-Iraq war, and his approach to abstraction evokes displacement, memory, nostalgia and violence. His fantastical landscapes, rich in aromatic colors, convey a fairytale orientalism that is both majestic and medieval. The use of color comes in a very intuitive way, driven by the mood of the day and the organic preponderance of one color over another. While working on a painting where blue is predominant, he might imagine the next one to be black, and so on. Amid his lush surfaces, splendor gives way to embellished anarchy and carnage as onslaughts of painterly gestures replicate the chaos of an attack. The fractured background, reminiscent of stained glass, is inspired by his recollection of the sound of shattering windows during bombings. This synesthetic connection between auditory memory and visualization is consistent throughout his work.

Ali Banisadr compares his work to a carnival parade. A lot of his work deals with costumes, masks, hiding behind your identity. In fact, many people told him to go and see the carnival in Venice. Growing up in Iran — during the Islamic revolution and the eight-year war — and then moving to the US, to the opposite side, gave him the ability to think about East and West and to maintain a kind of civil war in his head. To see both sides, which is reflected in his work by the oscillations between abstraction and figuration, detail and background, has become instrumental for his practice. Banisadr has nurtured an exceptional state of mind that can be described as the possibility of seeing both sides of a coin at the same time. The figures in his paintings can be seen as gatekeepers of systems: cultures, eras and religions.

Ali Banisadr pushes the boundaries of what we understand as painting. His work is not merely poetic; it is, indeed, pure poetry. Banisadr invites viewers into a universe that is as quiet as it is chaotic. His paintings, often rendered with oil paint applied to linen canvas, are lyrical to a degree that sometimes you forget the hints of figuration he injects into the composition; you want to simply follow the rhythm and free your spirit from any kind of constraint set by the rules of representation. In his explosive, exuberant canvases it is hard to pinpoint the exact nature of the action, but there is a lot of it, all compellingly allusive. His titles always suggest political machinations that merge fact and fiction. With their amassing of so many small marks and strokes in a palette variously fiery or verdant, his paintings are riotous and chaotic, creating scenes of what could be either paradise or a battlefield.