In a 2003 letter titled “Dear Editor,” Adrian Piper asks, in various permutations, that no modifier indicating her political identity be amended to her professional title: “Please don’t call me a black artist. / Please don’t call me a black philosopher. […] Please don’t call me a woman artist. / Please don’t call me a woman philosopher…” The demand to be addressed primarily as an individual of infinite difference rather than a representative of various subject positions echoes a sentiment found throughout much of Piper’s art writing and criticism, in which she speaks back to those whose laziness or lack of self-awareness — often emerging from their own unconscious investment in gendered and racialized power structures — leads them to misapprehend her work. Piper’s tireless defense of herself and her artwork from such misapprehension, and her consistent refusal to be relegated to uncomplicated racial categories, demonstrates a desire for space to be made for difference, and for the art world to shift toward organizing principles that are not premised on marginalization. “In my work,” she writes, “I struggle with familiar preconceptions and anciently serviceable labels — ‘black,’ ‘white,’ ‘us,’ ‘them,’ ‘him,’ ‘her,’ ‘you,’ ‘me’ — both because they can be a tool of self-transcendence and because, predictably, I also feel stifled by them.” In 2013, for instance, Piper pulled out of a survey exhibition of black performance art. In her letter to organizer Valerie Cassel Oliver she suggested that rather than the continued segregation of “ethnic” art, efforts be made to build multi-ethnic exhibitions in which a variety of artists and their works could be considered alongside one another.

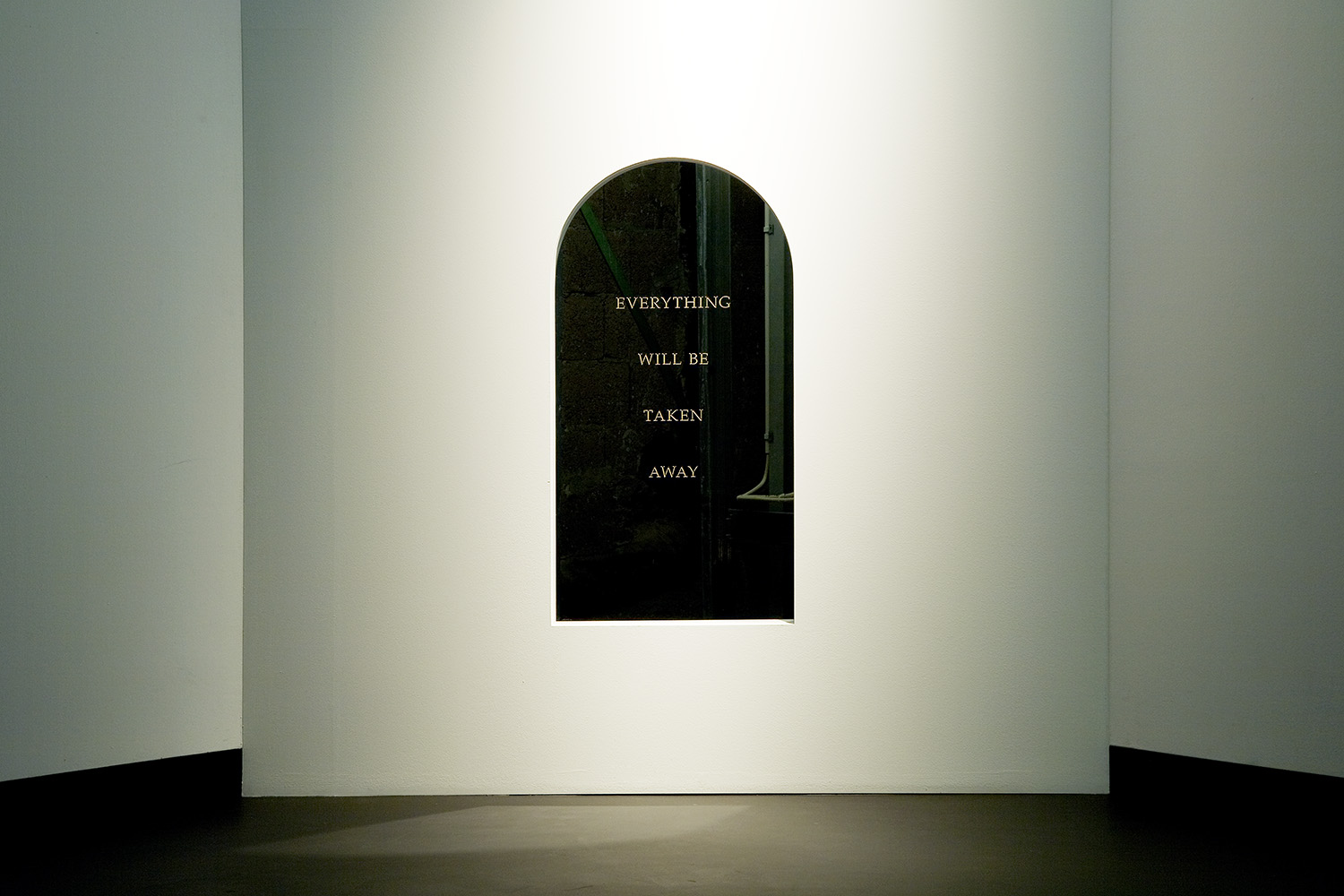

Shortly after she rescinded her participation in that exhibition, Piper presented The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1–3 (2013–17), the installation and participatory group performance that later earned her the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennial. Participants are invited to sign a personal declaration in which each vows: “I will always be too expensive to buy,” “I will always mean what I say,” or “I will always do what I say I am going to do.” The minimal installation of three austere reception desks and attendants is characteristic of Piper’s work. Often her provocations urge readers, participants, and onlookers to confront the scope of their own morality. (Her mixed-media installation Cornered, 1988, is one such subtly incendiary work. The white-passing artist declares herself black, and then calmly explains that most Americans who consider themselves white are five to twenty percent black. “So if I choose to identify myself as black whereas you do not, that’s not just a special, personal fact about me. It’s a fact about us. It’s our problem to solve. So, how do you propose we solve it? What are you going to do?”) It comes as no surprise that Piper appears, professionally at least, to have successfully committed to each of the three contractual clauses in The Probable Trust Registry. Throughout her career the artist has sacrificed greatly to stand for what she believes in, one extreme instance being her refusal to ever return to the US after she found out in 2006 that she was on the government’s suspicious traveler watch list. Her art practice has been a lucid and invaluable contribution to an art world she often strives to hold accountable.

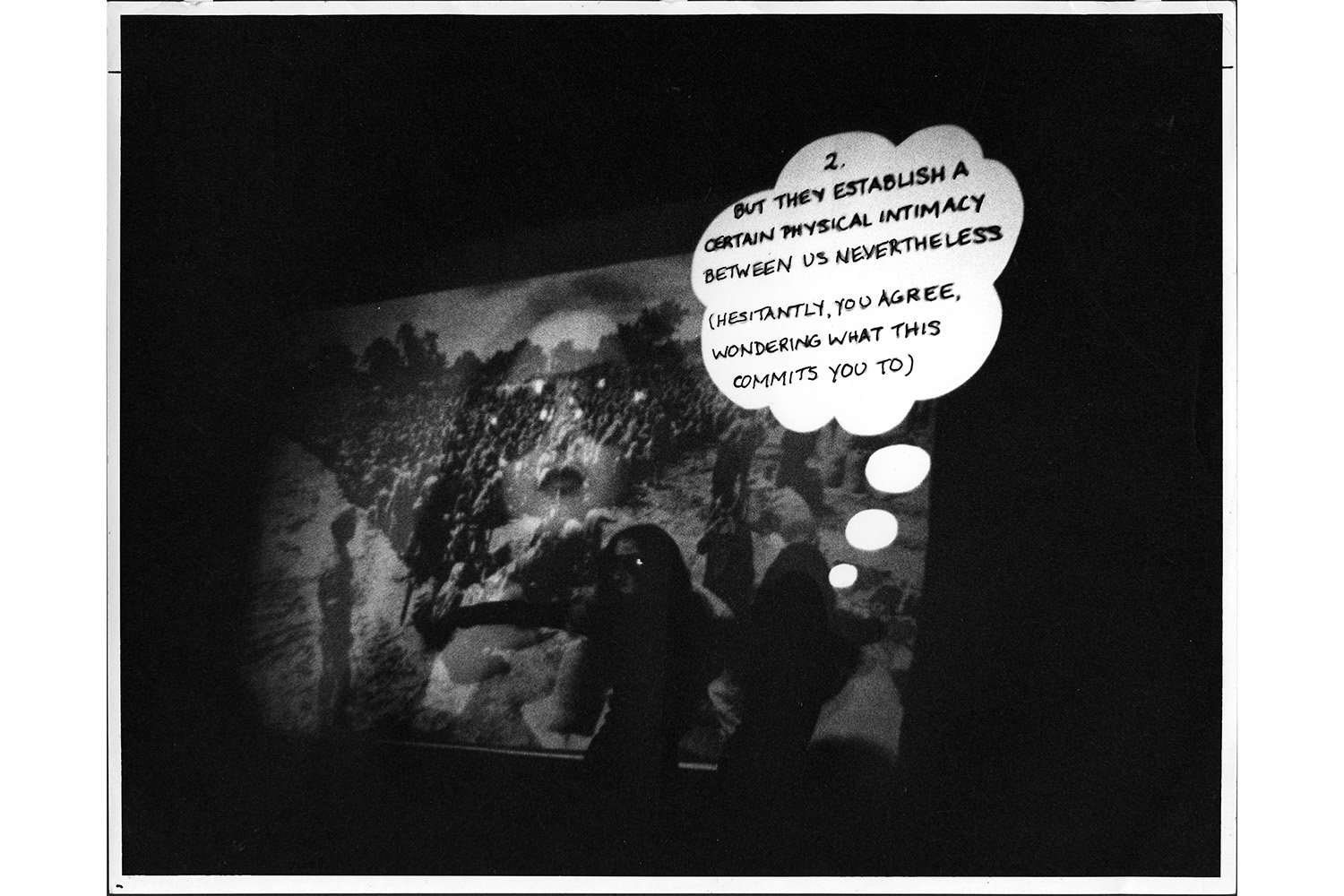

To this end, Piper develops a concept of cultural racism that she differentiates from economic, legal, or social racism. “The varieties of cultural racism are all ways of averting one’s gaze from the immanent specter of the Other,” she writes in her 1988 essay “Ways of Averting One’s Gaze.” Written in the second person, the text includes readers’ imagined retorts in parentheses:

Those of us on the cultural margin face a couple of extra challenges to give your lives drama and excitement. First, there is the challenge of getting those of you there, near the center, in the mainstream, to acknowledge our existence, so we can peaceably obtain resources and get on with our lives in this world we share. [Who, me? Are you talking to me?!] The moment when we stop being invisible to you is a highly rewarding one. [I don’t know what you mean. I’ve always liked black people. And anyway I’m not mainstream either. I’m an outsider, too…]

Here Piper describes the challenges of exclusion, but doesn’t look to inclusion as an antidote. Rather, inclusion produces its own perils. The latter problems occur in the realm of visibility and naming, where those on the art world’s margins, as Piper explains, attempt to “dodge the specious categories by which you try to make us safe and familiar; the linguistic pigeonholes by which you thereby consign us once again to invisibility.”

In the late 1980s and into the ’90s, Piper began to receive increased attention — she was included in more exhibitions, and received more reviews — as a result of the performances and conceptual work she had done over the previous decades as a member of the first generation of conceptual artists. This stereotypical categorization of marginalized artists Piper points to is most visible and explicit in art writing and criticism, and Piper persistently refused the “rampant factual misrepresentation of [her] work” in letters and essays that sought to rectify these misinterpretations. Piper carefully itemizes the use of violent language and rhetoric, which manifests in most cases as unsupported claims and arguments, does not distinguish between the work of art and the artists themselves, and/or is informed by a stereotype associated with the artist’s ability, gender, race, or sexuality. “I was the first and only African American woman artist given serious and sustained recognition by the mainstream art world,” she explained in a letter to the editor of The New York Times. “So I recognized the necessity of this task as part of the price of breaking new ground.”

One of Piper’s most noteworthy efforts to this effect is a 1987 letter to prominent critic Donald Kuspit, first published in Real Life magazine and accompanied by a drawing of the artist being strangled by words and another of the critic’s face on the body of a cockroach. Throughout the eighteen-page letter, Piper cites and systematically responds to Kuspit’s essay, dropped from the catalogue for her retrospective but then published, in a slightly altered version, in Art Criticism, a periodical Kuspit edited. In the letter, Piper breaks down the ways Kuspit uses a psychoanalytical approach to dehumanize her and say her work is the result of personal neurosis. “You are, of course, entitled to your speculations,” Piper offers, “as long as you make clear that that is what they are. But as they stand, most of your remarks are framed as factual statements about my psychological makeup.” Repeatedly quoting Kuspit’s material and responding in turn, the letter is almost conversational: “‘Piper… wants, almost hysterically, every condition for her performance to be just right, including its interpretive aftermath.’ / Donald, this is really very silly. I don’t understand why you’re doing it. Don’t you realize how paranoid all this makes you sound? You don’t need to depict me as a mad housewife in order to ensure the value of your own critical insights.” In calm and measured rejoinders Piper systematically shows that Kuspit’s comments about her work actually say more about his disregard for facts and his general biases than they do about her practice.

Recently arts institutions have increased their focus on marginalized arts practices and made greater public efforts toward inclusion and diversity. The nature of the hierarchies and the structures of the institutions have largely stayed the same, however, and a lot of contemporary criticism still carries the biases and carelessness Piper outlined. The last chapter of Christina Sharpe’s book Monstrous Intimacies, a set of case studies that departs from theorist Saidiya Hartman’s research into the ways in which the afterlife of slavery continues to inform our interpersonal relations, is dedicated to a close analysis of Kara Walker’s work, and the critical responses it has garnered. Sharpe notices the pose of nostalgic innocence adopted by “those (white) (re)viewers of Walker’s work who absent themselves from her dialectical practice while rehearsing a whole catalogue of names and acts for the black characters in the silhouettes.” They only see the black figures and deny or miss the white figures, even while “There is … no plantation romance or plantation slavery without white people, and Walker’s silhouettes contain many diegetically white characters in the black cutouts as well as in the white ground.”

Sharpe also discusses a “vitriolic” 2003 review by Kuspit, who asks what the point is of Walker dredging up the subject of race after “the civil rights surge of the 1960s has passed into history. Prejudice remains — against Asians, Jews, women and gays as well as blacks — and, these days, perhaps most of all against heterosexual white males, but there’s no special pleading on their behalf.” Kuspit, like other critics and viewers, is hard bent on disregarding any aspect of the work that might implicate his own subject position, and this lack of self-awareness maintains hierarchies that are fundamentally premised on blackness being different and Other to the straight, white, male perspective taken to be neutral. As Sharpe concludes, most of the audience reads Walker’s work as being exclusively about black people even though it depicts scenes from the antebellum south, when whites were integral to the system of slavery. By their abject denial of any complicity in the afterlife of slavery, these kinds of approaches contribute to the erasure of whiteness and maintain the structures of white supremacy.

That Kuspit recurs as an example in this essay may seem excessive, but unfortunately his attitude is exemplary in that it characterizes black women’s work and ideas, and Piper’s in particular, as threatening. Their perceived threat lies in their clear, critical reads of art-world economies and pervasive, quotidian racism, both of which are deeply entwined with white supremacy. Jamaican theorist Sylvia Wynter writes that we are conditioned to respond to aesthetics in a way that reinforces the current economic order and its attendant racial hierarchy, and she describes how established critical reading practices support a white, hetero-patriarchal hegemony. According to Wynter, narrative, and its attendant aesthetics, has the power to shape our whole worldview, and has been instrumental over the past five hundred years in determining who is and is not considered to be human. Antiblackness describes the attitudes and behavior of those who believe humanity is reserved for a select few, and who rely for their sense of self on an oppositional Other.

Piper’s criticism and artworks draw attention to the kinds of systems that perpetuate these hypocrisies of inclusion. In the introduction to Out of Order, Out of Sight, two volumes of Piper’s collected writings on meta-art and art criticism, she recounts the numerous times people in the art world were punished for supporting her. The perceived threat of her work, she explains, resulted in these supporters’ loss of “funding, their professional status, their jobs, or their voice in the community.” Piper herself received considerable backlash, not only as an artist but as an academic and philosopher, all of which demonstrate the material repercussions that derive from the perceived threat in her work and her ideas.

What Piper’s practice of responding to misinterpretations of her work makes clear is that within the art world, antiblackness is partly manifest in critical reading practices. In other words, how we see and understand is deeply embedded in our sense of the world and the narratives that reinforce its structuring hierarchies. It follows that the stakes of art and art writing are determined by this relationship between narrative and aesthetics, the stories we tell about the things we see. Along with other decolonial thinkers, Wynter argues that a major paradigm shift will be necessary for the world to change, that this shift can occur if and when we become self-aware of how our ways of looking are rooted in certain hierarchies. In this way, Piper’s work can also provide a certain set of emancipatory tools. Her callouts are a diagnostic of the deep, structuring influence of capitalism and white supremacy on the discourse of contemporary art. By drawing attention to how our entwined positions affect our relations to each other, Piper’s art and writing provide the guidelines for a more just way of seeing and being in the world.