– Eliel Jones

Eliel Jones: When we recently met in your studio, about a month or so ahead of your show at Camden Art Centre, one of the first things that we spoke about was heartache. Even though I didn’t know much about what you were working on or what you were going to be doing for the exhibition, the experience of heartache was palpably at the center of your thinking and doing. That was the initial impetus for wanting to have this conversation with you, perhaps a little selfishly, as I also have been feeling a need to deal with heartache; which, contrary to popular belief, isn’t just a conversation about love, but also about how this world can sometimes fall so short, and make us feel so low.

Adam Farah: When you came into the studio I had already been occupying it as part of a residency for about six months, and just before I started, in December last year, I had just come out of a romantic situation with someone. I don’t call it a break up, because we were never “officially together” or anything, but I would call it the transitioning of a relationship from a romantic one to something else that for a long time felt very unclear and non-mutual, for me anyway! And for whatever reason it was one of the most challenging things that I’ve ever experienced. It was such a hard place to be in that I just thought… actually, maybe I didn’t think, I just intuitively used the residency and the studio as a place to work through all of my feelings, and to think about what was going to hold me through the process of “healing.” In this sense, the show at Camden Art Centre naturally became about this mourning process.

To me it makes a lot of sense that I used the residency and this show in that way because the thing that got me into doing art in the first place was when my mom died, which was also a moment of heartache and mourning.

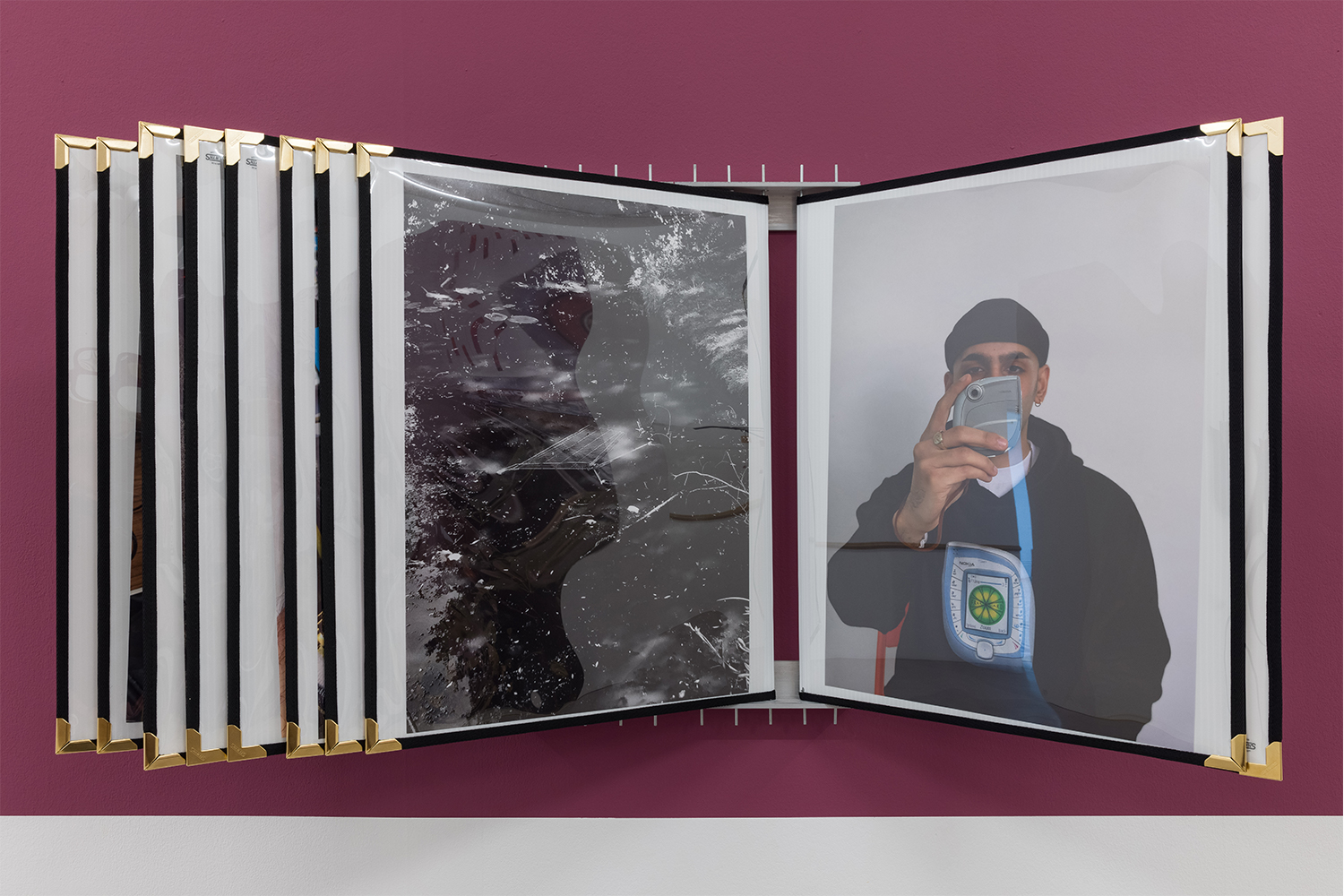

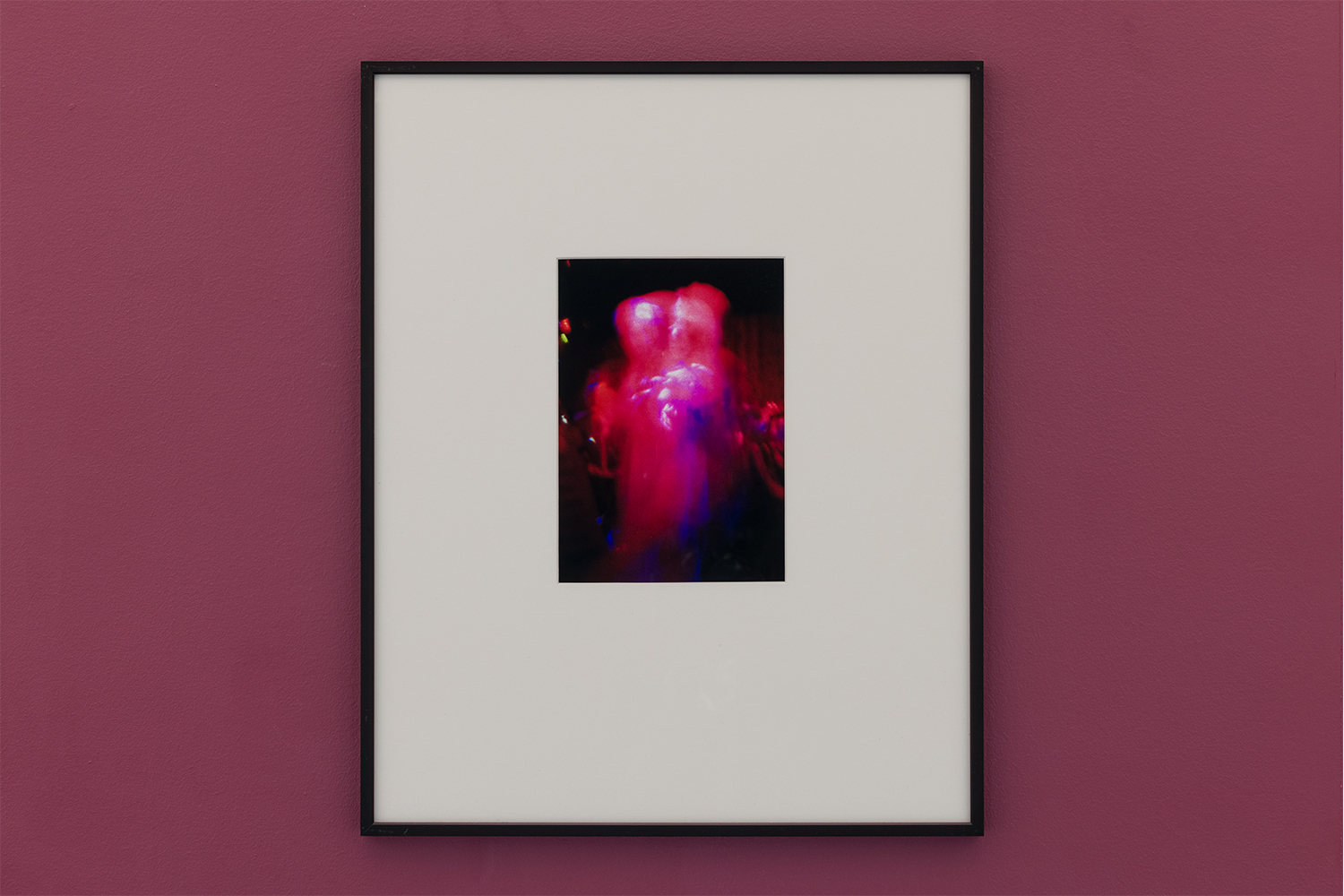

EJ: Both times that I’ve been at the exhibition I have definitely felt your desire to hold and be held; in the affective sense, but also very practically and formally, almost as if you’ve created a kind of waiting room. There’s a very palpable movement of time and feeling in the space, which seeps in and out of the artworks in various ways. Some of these objects are static or frozen and others are infinitely looped, which similarly renders them stuck or locked within a particular run of life or a moment. T1M£ (The Endz Portorbital Alchemical Mix) (all works 2021) demonstrates both states. For this work, you’ve installed a cream carpet on part of the floor, and you’ve covered it with a sheet of plastic, ensuring that its value and cleanliness will forever be preserved. On top of the carpet, you’ve placed a round steel fountain spewing KA Sparkling Black Grape drink, which is mesmerizing to look at as it creates a feeling that the supply never ends. In close proximity to these objects is the work titled My mum died too early to teach me about love and relationships, so I’m trying to learn something from the music I remember her listening to when I saw her crying — or at least connect to her spirit so we can share our heartache. The title is beautiful and beyond explanation, but the work consists of a five-disc CD Tower playing some of your mum’s most listened to albums, and in the background is a large-scale print of the fountain at Brent Cross Shopping Center in North West London. It feels important to describe some of these connections across artworks and their various temporalities — including the dated audio technology, which is present through other images and devices in the show — because it provides just a small viewpoint into the touching generosity that you offer us in this exhibition, which is infused with remnants of a personal past that seems to remain heavily present for you today.

AF: I wanted the exhibition to be a shrine to various moments, places, and people in my life, or that’s one way I wanted to look at it. There was something about time and mourning that was happening to me and that I wanted to bring into the exhibition, but also to create a space that people could “tune out” in – or perhaps that I could “tune out” in, seeing that I’m the number one visitor. I also like that you describe it as a waiting room, because that is literally what I feel I have been in these past months; I’ve been in this weird waiting room in my life. This period of the relationship transitioning that I referred to earlier triggered so much within me and my past, and I was telling myself, “Adam you really need to sit down and work on these things, but not how you think you’ve dealt with them previously; you need to sit down and work on them even if you feel that you’re hitting rock bottom, you need to sit with that. Even if you feel that you’re going crazy, maybe it’s time to actually run with that for a bit,” you know?

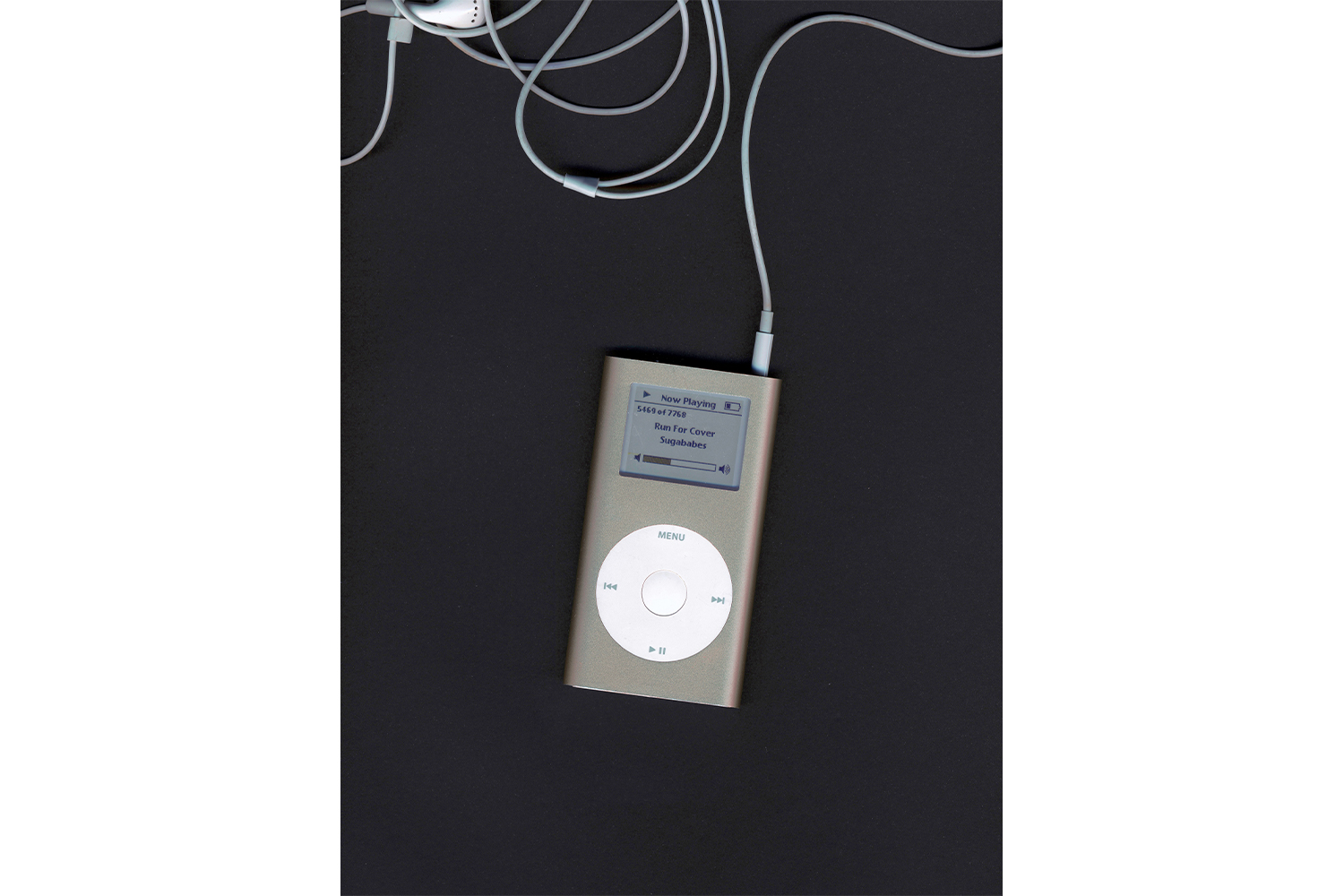

A lot of people came up to me at the opening and said that the show felt very nostalgic, which I’m just like, “ok.” It’s funny that people get that, and how can I say that it wasn’t my intention? When there is so much that could seem nostalgic, but it actually wasn’t. Maybe what I’m trying to say is that the reason why these things are there is because my relationship to time is different, just like it is for every single individual. And for me, I’m still working though those times; all these years later, I’m still working through these objects. Which is why they have such an affective charge for me, particularly the audio devices. When I go to the market and I pick up some of these devices, they just have this weird resonance with me because… maybe it’s a bit sad to say, but I haven’t necessarily gotten over some of the trauma or stuff from all those years ago, and maybe that is a bit of what nostalgia is as well.

EJ: I think it’s significant that you connect the use of these objects and their relevance or importance in your life with past trauma, which is less about a sentimental relationship to material than about the experience of an object and what that recalls or invokes, as well as its user experience.

AF: Yes, I mean all of these objects represent different moments of my life, which I feel like I am still trying to work through; especially the period of me being at school — one of the most stressful and traumatic periods of my life, which I’m still working through as an adult now. On the flip side of that, the devices also represent the good parts of these times as well. When we had them in school so much of the sociality and creativity there revolved around these devices. We just got them and we were figuring out how to make the most of them — like the Nokia phones and the PSPs (PlayStation Portable). There was a lot of sharing going on, using Bluetooth to share songs with each other or videos and stuff. I always say that the best creative community that I’ve ever had were my peers in secondary school. It was the most radical time for creativity in my life — at least at the level of communal creativity — and maybe there’s a part of me that misses that a little bit. These devices also symbolize markers in time, and just how rapidly things moved within a certain period when everything accelerated so quickly, both in regards to technology and capitalism as well. I often think about how that also affected us socially and emotionally, and about how we didn’t really have time to catch up with ourselves in that regard and properly process the formative things we were experiencing. Perhaps every generation feels like this, but I do think we had to grow up very quickly and accept it as being fine.

EJ: It’s true, a lot of these devices disappeared very quickly; or not quite disappeared, but their alternatives and replacements came around very quickly, bringing with them a level of social and political change that I do think has been historically unprecedented. There is a lot that can be said on this, but the loss or diminishing of social interactions feels relevant to bring up, because all of our connections now are so heavily mediated by devices. At one point the technology available required our presence as a means of facilitating a conversation or an interaction. You mentioned Bluetooth — I mean, Bluetooth only worked if you were less than a few meters apart from someone! These devices necessitated presence and togetherness in ways that, whether virtually or IRL, the space of sociality was still premised on real human interaction and exchange. It’s sad to think that “progress” was seen as the lessening of that desire or need; but also unsurprising, as the capitalist, neoliberal machine depends on us becoming increasingly more individual and unconcerned with — and for — each other.

AF: Definitely. It was also very much about streamlining and professionalizing interactions and communication practices, because these technologies were still very awkward for a long time. For instance, think about recording the radio onto cassette tapes; that was a very awkward endeavor! So people who were doing that were artists really.

EJ: This idea of artistry or craft that you allude to is also based on the device’s need for human input. These objects asked us to do something with them, rather than already being fully programmed to do those things for us. It’s completely antithetical to today’s premise of algorithm technology, where devices already know or very quickly can learn everything you’d like them to do based on a set of principles, patterns, and behaviors.

AF: Yes, I do worry about that in relation to our capability to pursue our own true desires, and to create real friendships and all different types of human connections. You used to make the effort to make a mixtape for a loved one or someone you had a crush on for instance. Now Spotify does that automatically for you; but Spotify will never be able to truly empathize with the love you have for another person!

EJ: I actually not so long ago made a CD mixtape for my parents in an attempt to emotionally and sonically come out to them. I had already come out years before but somehow I was still feeling very frustrated about not being really that comfortable with myself around them in all my sticky queerness. I think music was able to express my feelings very directly, and when I was a teen we bonded over it, even if with a little bit of shame. They didn’t really end up playing the CD while I was visiting them and I got really upset, so this simple playlist ended up becoming a bit of a burden that I still hold on to till this day.

AF: I 100% get that. Maybe you should play it as part of the installation at Camden.

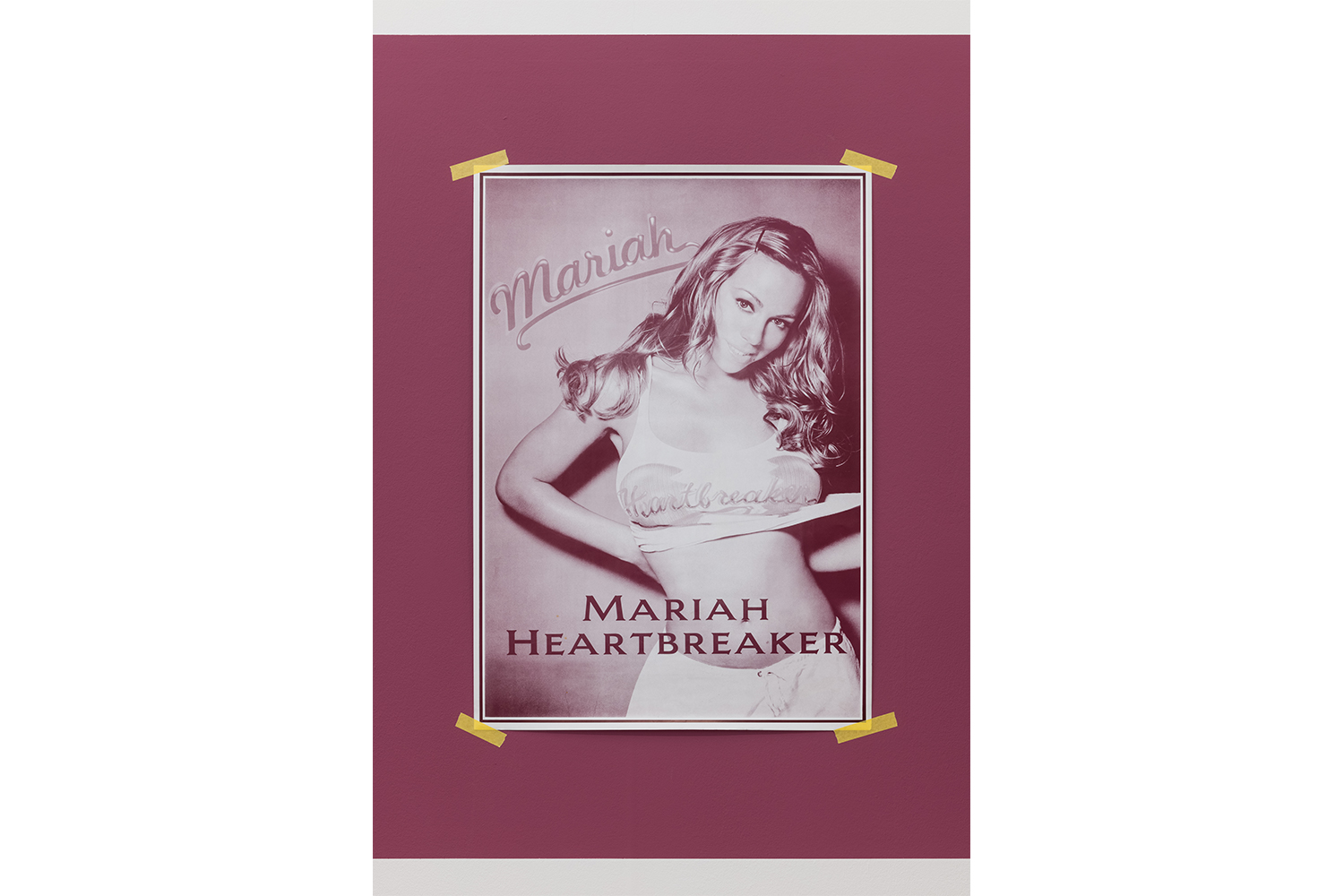

EJ: [Laughs] Ok! Another time that I tried “camping it up” with my family was by doing a lip-sync performance of Mariah Carey’s I Want to Know What Love Is (my usual karaoke go-to song). That was perhaps a more successful attempt at being more comfortable with my family and my queerness, but it only worked because I was pretty drunk.

AF: Sometimes you have to force it a bit!

EJ: Yes, I think that was the idea. Mariah is also very present in your show at Camden, alongside other divas. How did you come to introduce these pop artists into your practice?

AF: When I went to art school I quickly realized that I was in this really rigid environment in terms of how culture is thought about, in that I started to see that there were these very hierarchical judgments on art and culture, to the point where people who had genuinely influenced me — like Mariah, Janet, Madonna, and Whitney — were just seen as these really shit pop singers who weren’t true artists of integrity. This was at the time of the height of the post-internet movement as well, and that was adding to it because people would use pop references in this very ironic holier-than-thou sense. I remember feeling frustrated about this, but I was too young and not “learned” enough to be able to express why exactly that was frustrating me — why this very ironic, very agnostic scene and environment wasn’t vibing with me. It was ultimately because that’s not where I came from. I came from this very spiritual and soulful environment. Let’s forget this thing about belief, because it’s not about that. I mean, I was still working through my religious beliefs when I was in art school, and that was a complete “no no” as a conversation, even more so than Mariah! So I ended up rebelling against it and leaning into the sincerity of it all. At the time I read this pretty formative book called Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste by Carl Wilson. The whole premise of the book is him talking about why he hates Celine Dion so much. And within it he delves into all of these things about taste and how a lot is informed by different class, racial, and gendered positions, which I think it’s really important to acknowledge. When I was at art school everything was being taught through the lens of that “white-male-straight intellectual objectivity,” which wasn’t very helpful for me.

EJ: It probably wasn’t very helpful for anyone!

AF: Exactly. So I started to play around with that, and asked myself: What are my philosophies? What are my theories? And where do they come from? Because I always said that, for me, a theory is just dwelling on a way of being, or a way of living. So I was dwelling on those things present within my life, and that’s why I like to flippantly call things theories, like “Bluetooth theory” or “Mariah’s theorizations around the moment.” And besides that, nobody can deny that — even if you think that pop music is shit — Mariah is one of the best pop songwriters ever. She’s an amazing poet and creator of imagery, and I wanted to lean into that in this period with this show as well because I always had this discomfort about being called an artist anyway, so I started to call myself a visual poet. I’ve always found it funny that you make art and then automatically everyone wants you to explain it with words. Nobody asks the poet to explain their poetry with more words; people often sit with it a bit more before they ask someone what it is about!

EJ: You mentioned sincerity earlier, but this is also about honesty (both of which are qualities that are often missing in a lot of contemporary art, perhaps even frowned upon?). The reason why I love a lot of pop music is because of its ability to speak in very direct ways from the experience of the personal to the universal. You can insert your own heartbreak, your own pain, your own process of mourning, your own joy into these songs, in a way that they actually can become about yourself and other people simultaneously. In this way it’s perhaps one of the most accessible and far-reaching forms of expressions out there. I can’t think of many other things that facilitate that type of personal engagement, and I think your show at Camden is both a celebration of that but also an actualizing of its potential in the context of your own life.

AF: For sure. And that’s what Carl Wilson writes about in his book. He goes and talks to all these Celine Dion fans and they’re all saying how she helps them get through something, or she’s been there when they got married, or at a funeral when someone died. How can you deny the experience of millions of people? Those are real human experiences, no matter how cringe you might think it is! So maybe stop being so judgmental.

EJ: I think the judging has a lot to do with feelings, and how we as a society legitimize experiencing them in the first place — particularly what gets given a green light in terms of what is a valid way of experiencing a feeling or not. It’s also about whether it’s deemed genuine or worthy — whether something feels “real” or not to someone — and all too often there is a lack of recognition and respect towards the fact that we all have different ways and reasons for feeling things. It probably also ends up coming down to a deeper problem with empathy and solidarity.

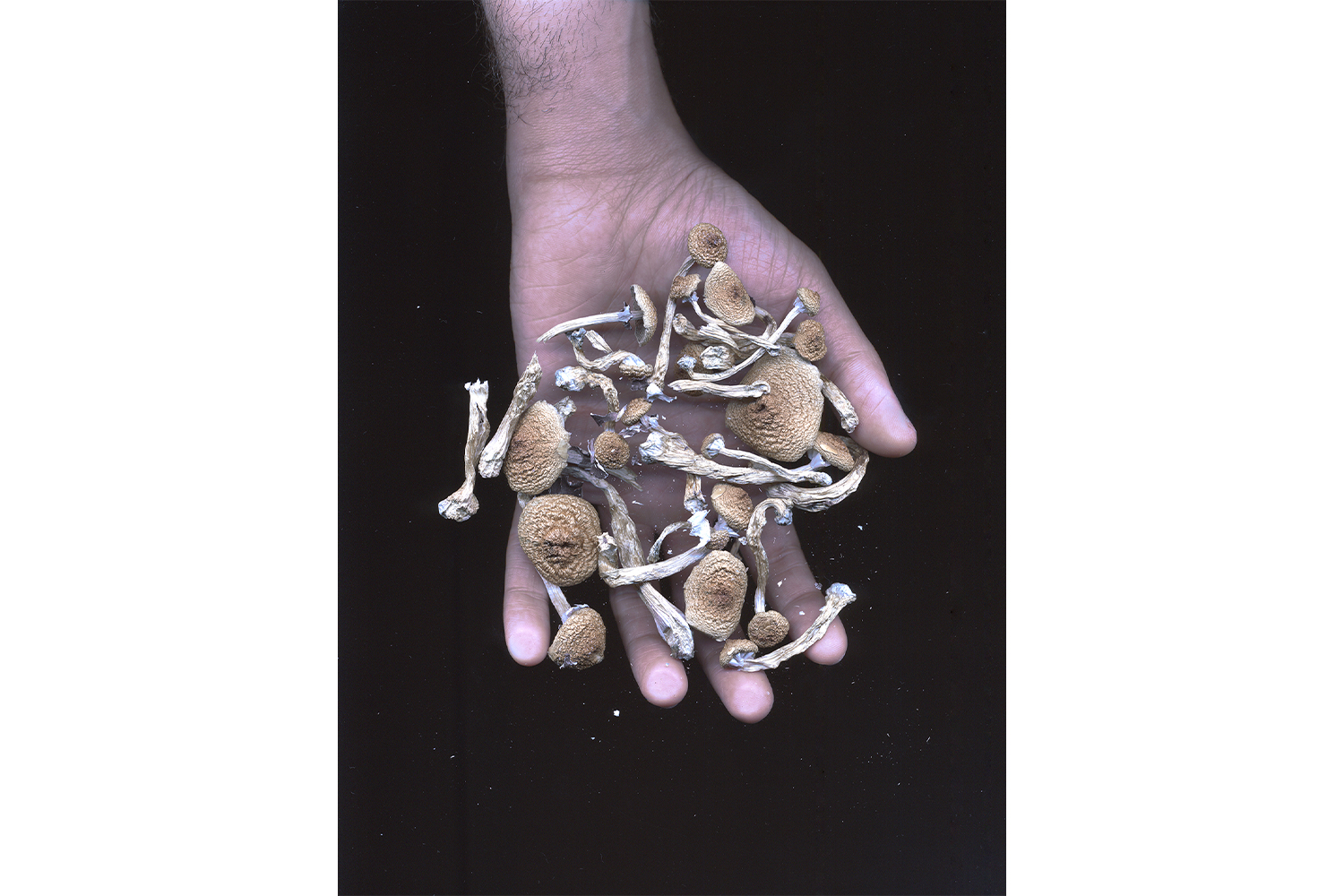

AF: It’s also about this weird judgment that comes from these so-called markers of intellect. For me I just went down this route because I’ve always acknowledged that there are different forms of intelligence. During this period I’ve been trying to lean into my soulful or spiritual intelligence, and that’s probably where my use of mushrooms has come in. One of the most noticeable effects that I’ve realized that microdosing has on me is that it does make everything way more poetic. Even the way that I speak starts to become more poetic when I’ve taken a microdose. I had this really big trip of six grams somewhat recently and there was a part of the trip when I was completely flipping out and I was super emotional, vulnerable and scared. I called my friend Christopher who is a poet, and I was talking to them whilst I was in the middle of this trip, and I told them: “I’ve called you because you speak like the mushrooms.” They’re a poet, so I thought that maybe they would understand what I was going through, because poetry is this kind of dis-identification with things, with our experience of the world around us. And that is what the mushrooms do; they help you dis-identify with all the binary structures of so-called reality, to the point where everything is just this poetic universe in all of its lightness and darkness, in all of its good and evil and its seriousness and goofiness. The way the mushrooms teach you is by showing you that you really don’t know as much as you think you do. And we all need to realize that at some point, because it’s where real growth can happen.