Bruno Dunley: When I first started to think about this conversation, it occurred me that a common ground I perceive in both your work is the notion of the boundary of an art object. Both bodies of work seem to exist in a frontier where this boundary is at the same time questioned and demarcated, although in distinctly different ways and with almost antagonistic points of departure.

Paulo Monteiro: When I first saw Adriano’s work, I realized it had some connection with what I do. I did not know exactly what, but it made me think of some works I made back in 1986. That was the year I stopped painting and started doing sculptures. Those works no longer exist, they have been dismantled, but there is still some photographic documentation. I used wood, metal, caulking compound, rubber, which then I nailed together or leaned on the wall. I did it basically with everything I could find.At the time I had in mind a quote by Philip Guston in which he talks about being in his studio and looking at loads of paint on the floor, and he asks himself why it was considered “dead” on the floor but gained life on the canvas. This transition of something dead to something living was interesting to me. I kept thinking: “I’ll do something about it!” And as I did, I asked myself: “Is it already something or not?” So, I think there was something of these boundaries you mentioned, which remains part of my work yet today, because their transient aspect turns them somewhat into a dance: it is a gesture you make and no one else will ever see it again.

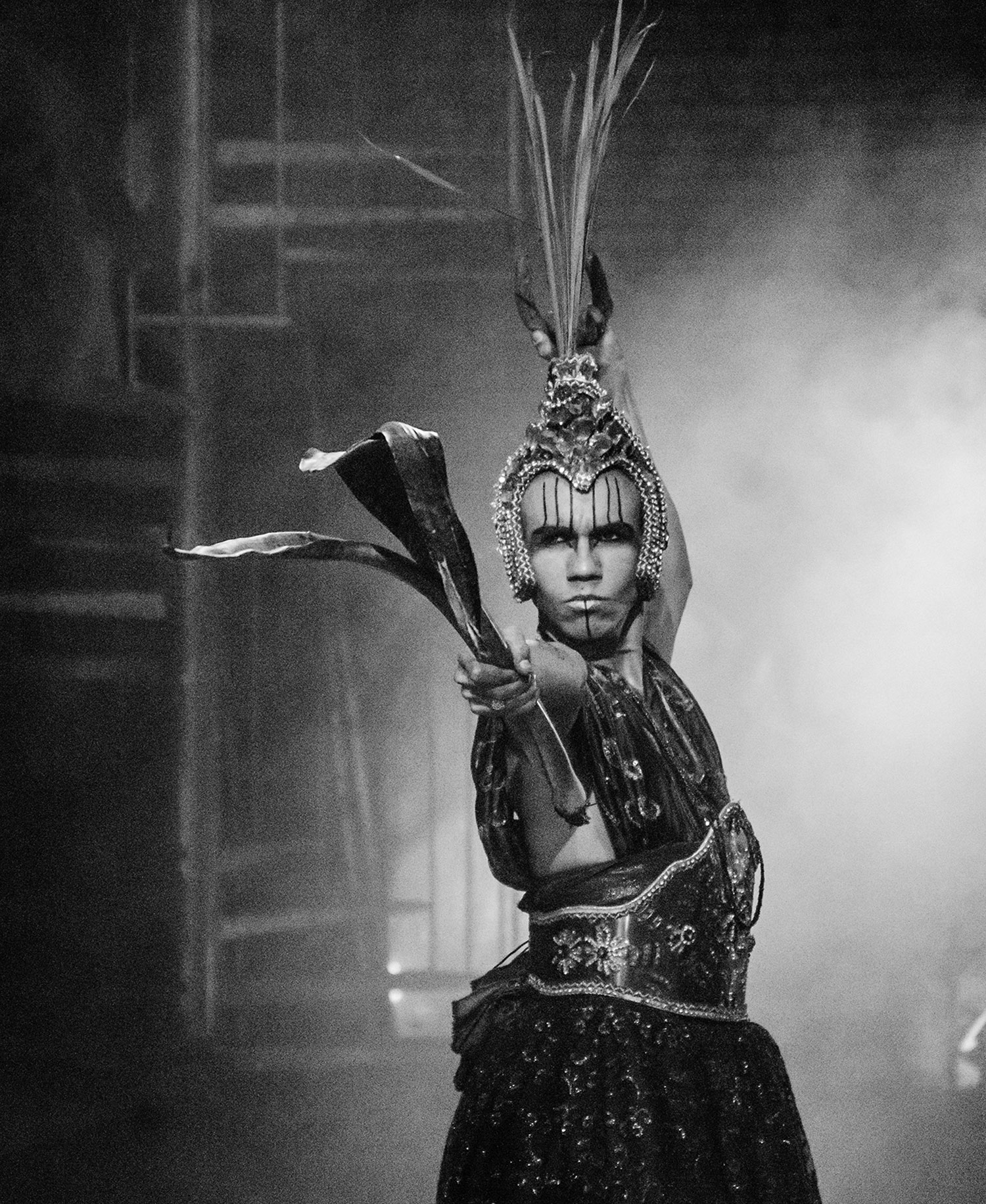

Adriano Costa: I have the impression that dancing must be another common ground between us. You do dance, right?

PM: I do classical ballet classes with my sister, Zélia Monteiro, who is a dancer.

AC: Well, I recall having seen a spectacle by Lucinda Childs that really impressed me. The presentation had a progressive sequence of movements. I see something of that dynamic in my work. Many times, I make works that are destroyed, but after a week or a year, they become something else. I am truly terrified of discarding things. In my studio there are pieces of cropped-out brush strokes that are kept for whatever reason, which might fit in as a solution or departure point at a given moment.

PM: Once I went to the streets holding a sculpture with a loose structure that I wanted to weld. It was a piece of iron with two tips, two barrels, and I wanted to do something with it. I took it to the welding guy and he said: “What are you going to do with this? Is it an antenna? An exhaust pipe?” Then I thought it could actually be an exhaust pipe, indeed. If I gave it to him, what would it be? An exhaust pipe. It really encompasses an ambiguous condition.

BD: When I mention this antagonism in reaching the boundary condition of the art object, as I see in your works, I am not only referring to this aspect in the finished work, but also in its point of departure. In Adriano’s case, the bottom line is accumulation. The work emerges through the articulation of mundane, apparently disposable artifacts that have predefined roles in society, as well as the remains of failed attempts at previous works. These junctions are delicate and often retain a sense of craftsmanship, which reinforces the meaningful, fragile aspect of a human presence while simultaneously activating a perception of strength and assertion when the work is finished.

I have the impression that Adriano’s works are always posing the question: “What is a sculpture? What is an art object?” They do it at the same time they claim autonomy and thoughtfulness in order to exist. This is where I see the idea of the boundary. His works are always struggling to remain alive, walking a tightrope.

AC: Many times, I do things that do not work out, but the issues you mention do exist. I think my subject is art itself, its procedures, whether it is a painting or a sculpture. But for me, to think or analyze the work as a form or object is not enough.

PM: Also because your work travels through other contexts.

BD: Exactly. It reflects the ideological system of values in which it takes part due to its artistic legitimation, its conditions and work divisions, as well as its monetary value. This is so strong in the world we live in that it makes me think that many people go to art exhibitions simply to contemplate money. After all, what are you seeing? What is at stake? I see that in works like Straight from the House of Trophy – Ouro Velho [Old Gold] (2013), and in part of your exhibition “La Commedia dell’Arte,” held this year at Peep-Hole in Milan.

AC: The work in Milan departs from my need to try to figure out my role as a South American artist working in Europe. My bottom line was the illegal work of African immigrants who sell purses, especially products from Italian fashion houses that are considered fetish objects, as well as the work of countless Brazilian transvestites in Italy — some say that up to 70% of prostitutes there come from Brazil. My position in the art system is not actually that different. And I obviously do not mean that sadly; there is a specific humor to my work.

Three works comprised this exhibition: International Division of Labour 1, International Division of Labour 2 and How to be Invisible in High Heels (all 2014). All talk about boundaries that should not be that stiff. I usually panic, for instance, when I read something about “Brazilian art” in the foreign media. This specific division bothers me.

BD: But for me what binds the power of the exhibition’s content is the sign saying “Brazilian wax.” “International division of labor” indeed! We export a waxing model!

AC: Actually, this is one of our most successful products in the entire world.

BD: Back to Monteiro’s work, the bottom line is to build a work whose aspect, in my opinion, questions the boundaries of an art object — basically what it is made of, the raw material. He takes wood, clay, lead, copper or paint, and by articulating them they are tempered. In the lead sculptures, for instance, it’s translated through the traditional features of language itself: weight, tension, materialness and gesture are the protagonists, thus producing an autonomy of thought. In this regard, I notice that the gesture is cardinal in the sculptures, as in the drawings and paintings. Concentrated gestures simultaneously edify fragile aspects. Such gestures convey resistance, the weight of things. This ambiguity of defining and annihilating adds an evocative element of exhaustion to the works. Hence the idea of the boundary once again.

PM: Indeed, I think like that as well, but my gesture is not an expressionist, heroic one. My work does not claim for transcendence or sublimation. It is not idealistic in this sense.

BD: I agree. It is not idealistic because the idea of lyricism does not exist like that. When I talk about gesture in your work, I refer to a remnant of the gesture and its collapse. I think that neither of you make idealistic works. They are rather mundane, more tied to the vulgar aspect of things. The vulgarity of Adriano is different from yours, Paulo, because the material he uses brings along several layers of social usage, function and behavior. You, on the other hand, use iron, lead, leftover paint. A lot is made from the intrinsic properties of materials. It is from the brutality of the matter and the dimension of an “accomplished thing” that the work acquires presence. There is no reverie, but rather a statement of “this was done!” and all the radicalism that suggests.

PM: It is different because, in my work, it is as if there was a shapeless shape. I always use the same construction. There is not much difference or formal variation; it is always a mound, something lengthy or an oval shape.

BD: Besides the inner space of your works, another important dimension is the space you establish when setting up an exhibition. I refer, for instance, to the set you presented in the collective exhibition “Where Were You?” at Lisson Gallery in London.

PM: This might as well be another point of convergence between my work and Adriano’s. When I set up an exhibition, I do not merely take into account the physical result of each work. For this London exhibition, for example, regarding the wall where I placed the reliefs, each work was always in relation to the surrounding space while also preserving its own body and identity. This makes the works themselves and the relationship between them acquire new meaning.

BD: The works incorporate a dimension from outside of their strictly physical boundary.

PM: Exactly. I’m interested in empty spaces and the differences between them. How does the work occupy the surrounding space? This suggests an external dimension to the object without relinquishing its internal dimension.

BD: What do you mean precisely by “internal dimension”? Does it relate to the intimate character of the object?

PM: I’m not sure how to define it, but there are many works of art in which the parts relate to an external space, the surrounding space. In an installation by Carl Andre, for instance, you are outside it and will remain so, but in dialogue with the space of the work. I feel that in Brazilian art this happens a bit differently, in general. In Hélio Oiticica’s works, the Penetrável [Penetrable] (1960s) series or the Nests (1970), for instance, you literally need to enter into it — there is always an internal pulse. This also happens metaphorically, and the titles reinforce this aspect. I do not know why things are like that in Brazilian art — and even in our works, to some extent.

BD: On the other hand, some of Adriano’s works, like Flag (2103), lead me to question identity, the demarcation of territories and power. Such questions are reinforced by the titles of the works, which confer other layers of meaning. In A Place Built to be Destroyed (2102), for instance, the title is pretty meaningful. It is as if part of his work was raised from a wasteland that is, at the same time, the world we live in and also the territory of art, with all that has been done to its boundaries and definitions over the past century. I also see some of this in Nós estamos às moscas [We were left nothing but flies] (2012).

AC: A Place Built to be Destroyed was made with lace, a very common material in handicraft work, which is also widely associated with the feminine universe. The work has these colors — blue, yellow, red — that can lead you directly to Mondrian. But when we think of the role of lace in the world, there is no such thing as this intersection of strong colors. This work has a formal aspect that is a clue, but actually I want to reach something else, which is a perspective of gender and behavioral attitudes.

When you think of the market value of handicraft, it is very low — that is, a work born to be killed. In this world of exchanges it has one of the lowest values. What are the layers of sense you want to be in physical evidence in a work of art? For me, they are countless. I see that in Monteiro’s work as well. That thing you mentioned about the material being fragile and tough at the same time, you know?

PM: I think there is this clue, indeed. Maybe the work of art is only a trail of thought, a junction of both material and immaterial natures, some sort of cerebral act.

AC: In my case, it is quite mundane, and becoming increasingly more so.

BD: But this does not make the work lose its reflexive power and commingle once and for all with the other artifacts of the world. It also mistrusts the totality of this mixture and saves a place to return such capacity to the world in a critical and poetic manner.

AC: In reality, when I say it is mundane, this is actually the place I want to reach.

BD: To go back to the store where you bought the materials?

AC: Totally. I feel like there is a beginning that later leads somewhere else and then returns. What are the possibilities of communication of a work of art in the world?

PM: I think nowadays there is a homogenization between the “objects of the world” and the “objects of art.” This issue concerns us, but I do not perceive much difference between doing paintings, sculptures or wall pieces. I am not worried about the status of the object — whether it is a sculpture, a painting, etc. What I am interested in is this transition of the common object into something “living.” I am interested in transforming a piece of wood, for example, into something that barely looks like a piece of wood.