“Pictures” is the title I gave to an exhibition, organized for Artists Space in New York City in the fall of 1977, presenting the work of a group of young artists who use recognizable images about pictures. I chose the word “pictures” in an attempt to convey not only this most salient aspect of the work, but also important ambiguities of it. As is typical of what has come to be called postmodernism, this new work does not respect the integrity of, nor address itself to the essential properties of any particular medium. It makes use of photographs, film, video and performance, as well as traditional modes of painting, drawing and sculpture. Picture, in colloquial usage, is also non-specific: a picture book might be a book of photographs or drawings; a film is sometimes called a picture show or a moving picture; and in common parlance a painting, drawing or print is often called simply a picture. Equally important, on a more theoretical level, picture, in its verb form, can refer to a mental process as well as the production of an aesthetic object. By using this term, I therefore wish to avoid references to mediums, as if they were ontological categories, and to aesthetic styles, as if art were somehow exterior to those activities which produce instances of it. In all of its usages, of course, picture carries the notion of representation, of copy. Implicit in the concept picture is that it is a picture ‘of’. Yet, in modern culture, the relationship of the picture to what is pictured has been obscured. Because the relationship of a mechanically or electronically produced picture to what is pictured is unquestioned (it is, after all, simply a trace, and is therefore one-to-one), it has been supplanted by an infinitude of indistinguishable copies, and the notion of an original is lost. We are left, therefore, with an experience that must remain, and in any case chooses to remain, with the picture itself.

This is the experience that is to be found in the work of a group of young artists currently active in New York. For them there is no question of a picture functioning as a transcription of the real. Representation is understood as the only possibility of grasping the world around us; it is not, therefore, relegated to a relationship to reality that is either secondary or transcendent; and it does not achieve signification in relation to what is represented, but only in relation to other representation. Representation has returned in this art not in the familiar guise of realism, which seeks to resemble a prior existence, but as an autonomous function that might be described as representation as such. It is representation freed from the tyranny of the represented. What these pictures show, present, depict, picture is only what is always already another picture. And if it may then seem that we are just twice removed from reality, from the source or origin, then it must be countered that everything in this work conspires against ever locating an origin, either within the work or exterior to it.

It should perhaps be made clear that these artists are, for the most part, picture-users rather than picture-makers. Their activity involves the selection and presentation of images from the culture at large. But they subvert the standard signifying function of those pictures, tied to their captions, their commentaries, their narrative sequences — tied, that is, to the illusion that they are directing transparent to a particular signified. What these artists provide is the possibility of readings that the culture which produces these pictures seeks to foreclose, readings whose multiplicity would contravene an ideology of the signified.

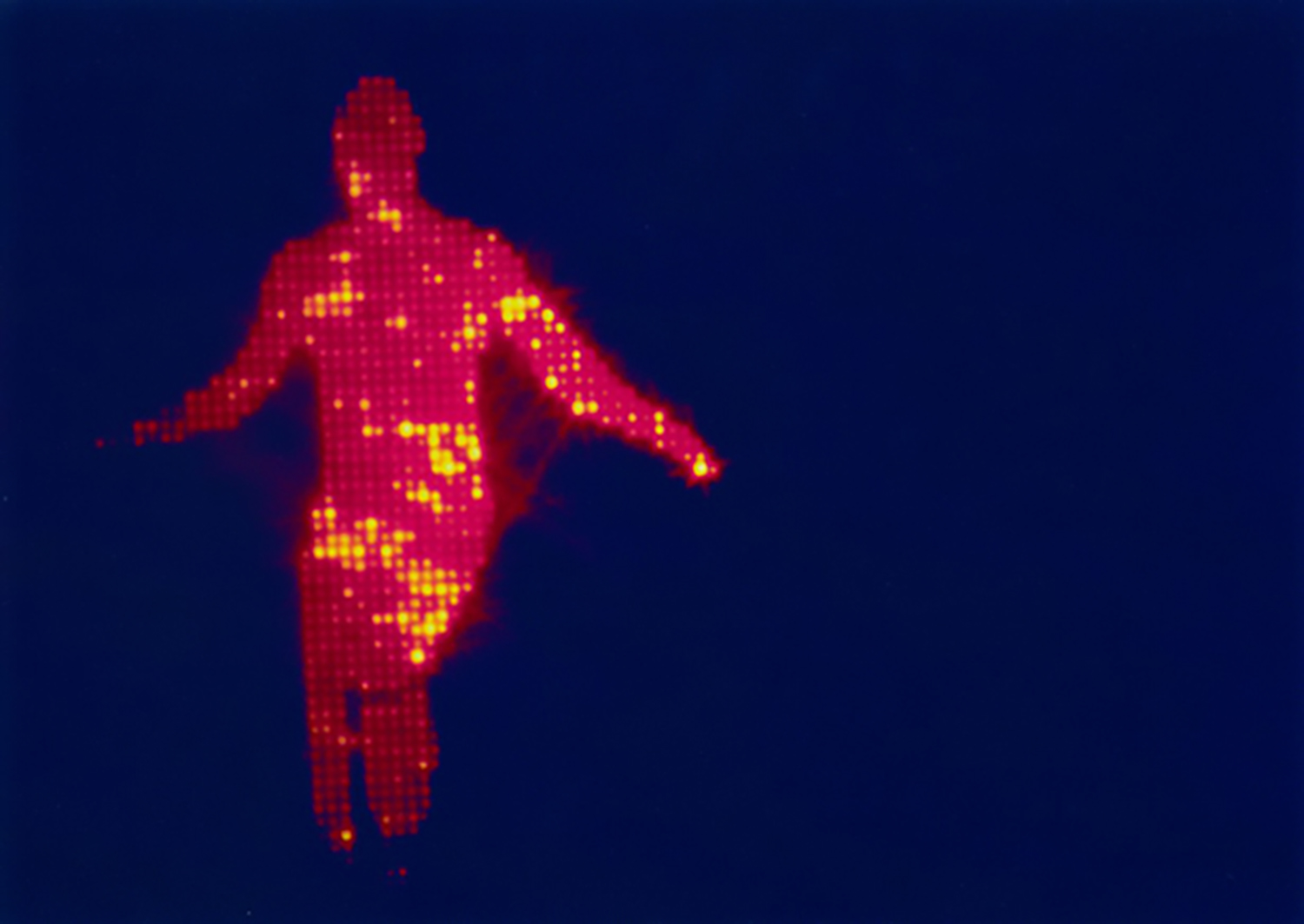

Here are a few examples: for his film The Jump (1978), Jack Goldstein used a shot of a dive from a high board. This stock super-8 footage was submitted to various processes of mechanical transformation, primarily rotoscoping, but also filtering and color printing. The resultant image is a sparkling red, silhouetted figure seen against a dark, blank field. This figure — sometimes discernable as a diver, sometimes simply a shimmering shape — leaps, somersaults, plunges and disappears. This happens very quickly, after which there is a pause and it is repeated (the film is shown as a loop, so that the repetition is potentially endless). But the expectation established in the repetition of the diver’s action is never satisfied. It always manages to take us by surprise and then to disappear before we really comprehend it. The picture is therefore illusive in a number of ways: by erasing the surrounding context of the live footage, Goldstein isolates and heightens the presence of the diver only to deprive him of any specificity. And in the performance of the dive, the figure slips in and out of legibility, as if it existed on the threshold that gives to signification.

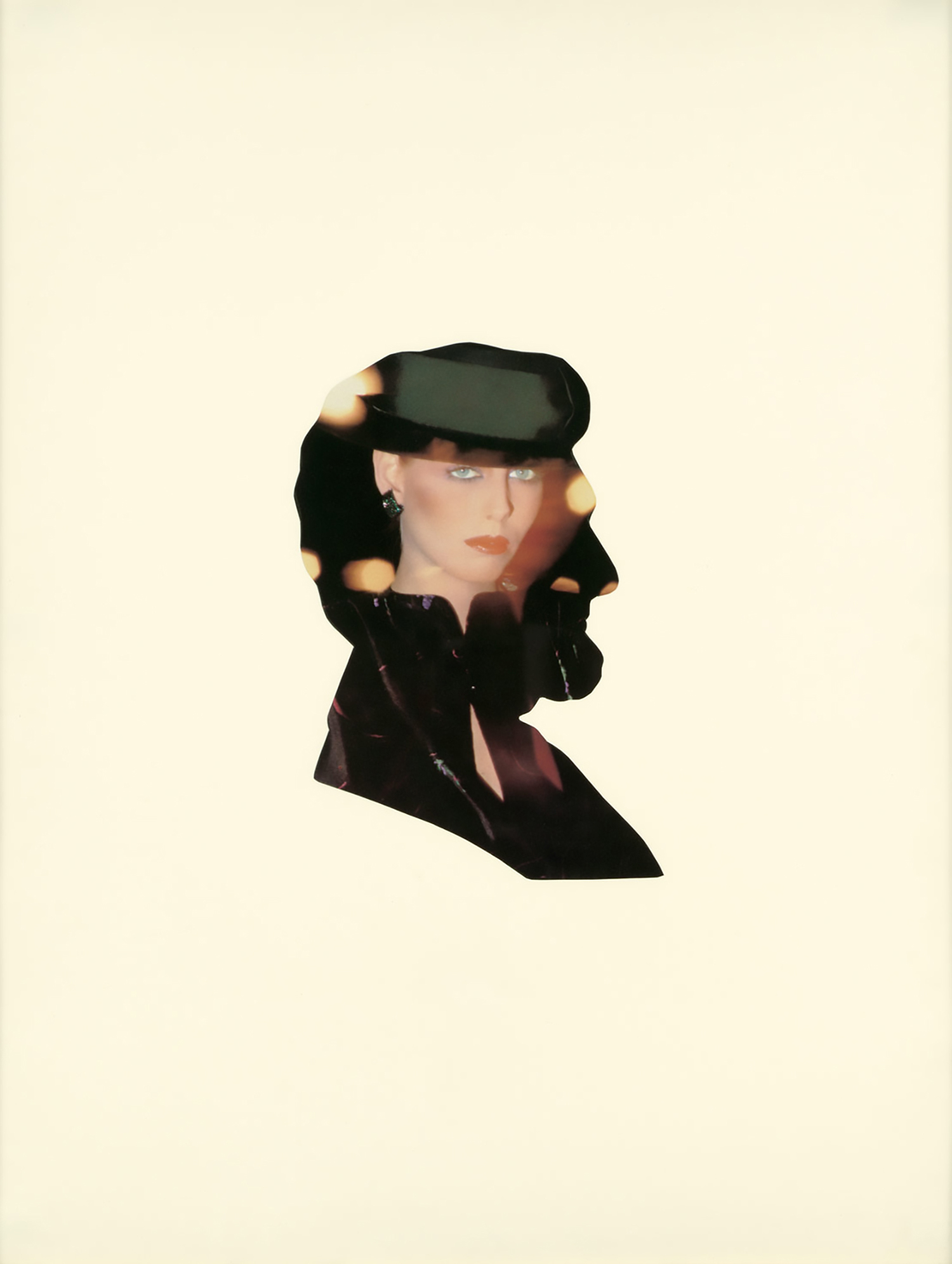

Sherrie Levine completed a series of works (“President” series, 1979) in which photographs of a mother and child, taken from a fashion magazine, are cropped according to the emblematic silhouettes of three American presidents: Washington, Lincoln and Kennedy. Through this rather simple gesture, she discloses a reading of these images through or as each other. Although technically related to the juxtapositions upon which surrealism depends, the shock of Levine’s pictures doesn’t rely on paradox. Her images, of a thoroughly mythologized status, are poignant precisely because they seem so rightfully, so naturally to belong together. There is in them a world simultaneously promised and denied. One could say that this is work that takes the “American dream” seriously because it has entrapped us all in a great melodrama of yearning.

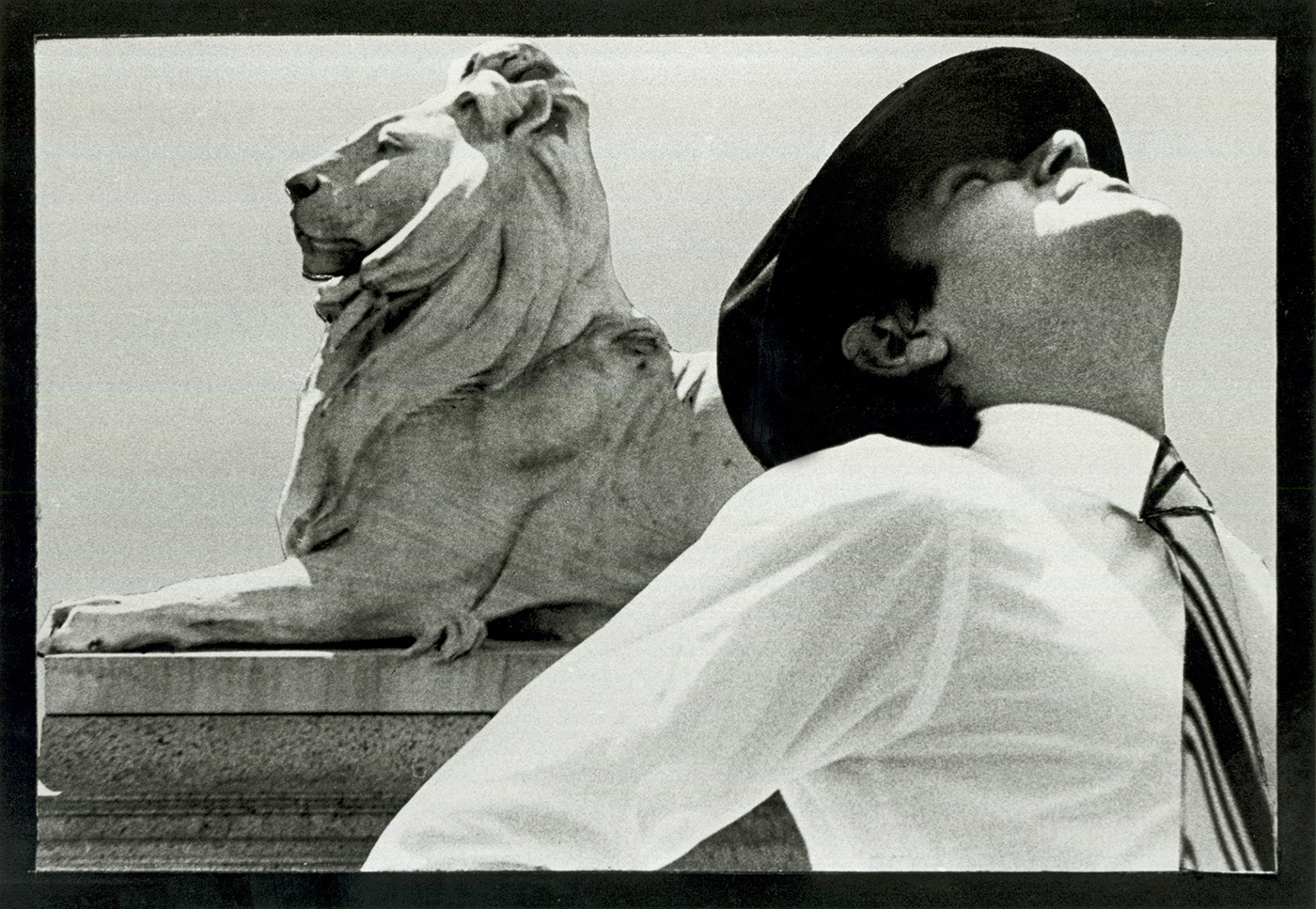

The central image in a performance by Robert Longo entitled Sound of Distance of a Good Man (1978) was a film showing the upper quarter of a man’s arched body, his head thrown back in convulsion. The posture registers a quick, jerky motion, and is contrasted to the frozen immobility of the statue of a lion. But what the spectators saw as that film unwound was only that image, i.e. only a still picture. To describe the genesis of this still image is, however, to involve us in a scenario that is utterly labyrinthine: the movie camera was trained on a montaged photograph, one of whose elements is the man. This figure is a composite of several shots of someone posed and dressed in imitation of a sculptural relief Longo made earlier the same year, that relief itself copied from a newspaper reproduction that was a fragment of a film-still from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Der Amerikanische Soldat (The American Soldier) (1970).

One cannot, of course, know this elaborate process looking at the performance, any more than one can see the super-8 footage from which Goldstein rotoscoped The Jump. What one sees is only the result, a picture whose manipulation of temporality and the ways temporality is figured in a static image, become a metaphor for the duration of that process.

Troy Brauntuch’s work uses pictures that have, from a traditional perspective, the most highly charged cultural load: pictures of the Third Reich. But these images — drawings by Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer, photographs of the Nuremberg Rally and Trials, etc. — are of an extremely opaque quality; they are fragmentary, blurred, banal, meaningless. Reproduced in book after book recounting the Nazi horrors, they are strangely mute about its magnitude. Brauntuch’s work is about the profound and irreducible distance that separates us from that history. Using commercial printing techniques and refined presentational values (framing and placement are as crucial to Brauntuch as the character of the images themselves), he fixes the distance recorded in those pictures forever in an aesthetic object.

The processes involved are, like Longo’s extravagant manipulations to get from a film still to a still film, feverish, futile attempts to make those images render up their secrets, the significations that humanist culture has told us they hold. And the resultant works are records of a failure to do so, of the duration of a gaze that has been fixed on those images, and its ultimate resignation.

There is about all of the manipulations of pictures in the works described a highly obsessional quality, a performance of a futile activity that seeks to uncover meanings that are said to reside in images but do not. But in the processes of acting out that obsession, other kinds of meanings are produced. Unlike the use of ‘found images’ in earlier modernist art (in Robert Rauschenberg, for example), the presentation of pictures in this work is less involved with formal transformations than with processes that must be called temporal. Not only do they involve time spent, time lavished, but they are about time, the time of reading (of a fixed stare), about the time of memory, and about those emotions which are fundamentally temporal: longing, nostalgia, presentment, anxiety, expectation, dread.

from Flash Art n°88-89, 1978