Connecting and collating people, things and information in a practice that often extends beyond the creation of discreet art objects, Heman Chong (b. 1977, Malaysia; lives in Singapore) uses the structures of language to talk about the idea of content. He does this through the production of individual artworks, but also through his work as a curator and writer — although such distinctions between artist, curator and writer can distract from the complexity of Chong’s purview, as his collaborations can take on many forms, regardless of the role he is invited to play. Chong rarely performs the part of cultural producer straightforwardly; he is generally ‘all of the above’ at any given occasion. Therefore, his activities don’t sit comfortably within the delineated categories that typically comprise the distribution of content. Books, exhibitions, institutions, paintings — all are vehicles for content whose structures come under Chong’s scrutiny.

In projects such as a collaboratively written novel, a video of web links, a fully functioning bookstore, public programs organized for institutions, or paintings of book covers, Chong carefully dissects and aggregates information, letting associations run wild. He presents partial threads of communication, disperses authorship and creates situations. The initial data for his works often originates elsewhere; existing content is transformed under his manipulations and then transformed again.

An early example is the collective book Philip. In 2006, Chong, along with Leif Magne Tangen, initiated a collaborative fiction-writing workshop at Project Arts Centre in Dublin. Together with other artists, curators and writers, such as Mark Aerial Waller, Cosmin Costinas and Rosemary Heather, among others, Chong embarked on the composition of a science-fiction novel. During intensive sessions spanning seven days, the group discussed, wrote and produced the small book. Not quite an exquisite corpse, Philip, named after the cult science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, turns fiction writing into an efficient collaborative labor. Even though each author brings a unique perspective and prose style to the novel, Philip is oddly coherent. It isn’t the best literature, but it’s pretty good. Is this evidence that the solitary genius of the writer is overblown? Creating a product that could also be convincingly produced under the semblance of a bureaucratic structure, Philip predates the self-publishing that now takes place in the e-book era — with runaway hit books composed by amateurs — but presciently anticipates the diminishing elitism of the author in contemporary publishing. As a collaboratively created artwork, Philip lives as a book and an artwork. It is both shown in exhibitions and read as a book. Like most of the projects that comprise Chong’s practice, there are multiple modes of presentation and possible interpretations to be found in a single proposition.

This multivalent logic continues in Chong’s 2012 work LEM1 (A Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Store), a fully functioning secondhand bookstore with outposts in London and Sharjah. In this case, the structure of the shop becomes the artwork, the books part of its composition. Sold for less than what they are worth, the books enter into a direct cycle of exchange between visitors. The organizing science fiction genre is important to the conception of the store, but it also simply functions as an exercise in genre. The shop’s focus touches on the distinctions between popular and specialized genres, expertise and taste. The project works to level discrepancies between aficionados of a field such as science fiction and that of contemporary art, as two particular audiences are merged into one setting. Further, the patrons of the bookshop who are seeking out science fiction literature must enter a commercial gallery space to peruse or purchase books. By opposing the conventions of these two sites and audiences, Chong diminishes their dissimilarity as locations of cultural consumption.

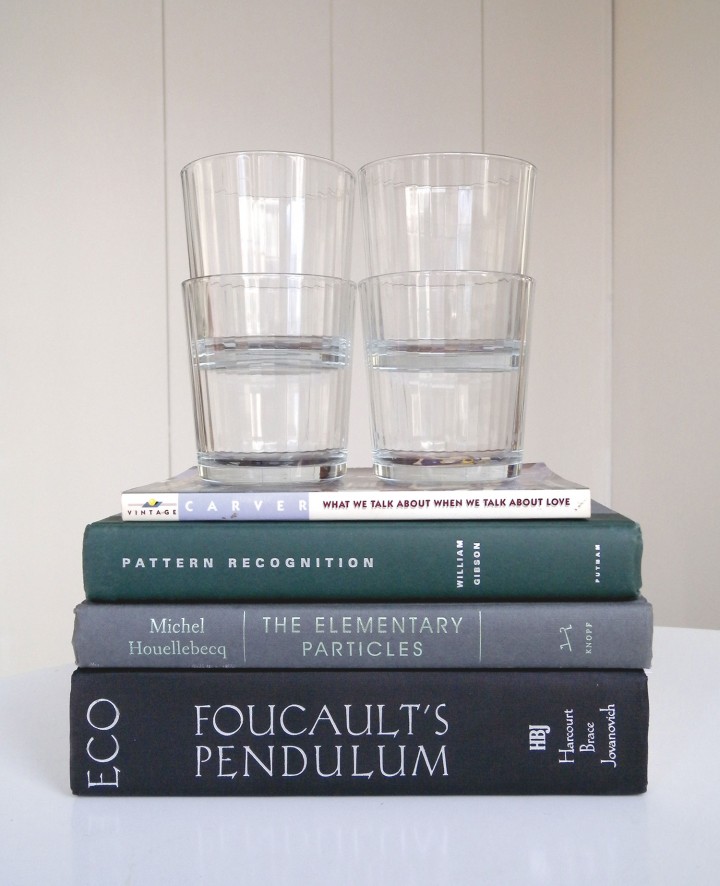

The conventions of genres are essential. By breaking them down, Chong reveals assumptions about the production and distribution of cultural content. In his series of Cover (Versions) (2009–ongoing), Chong has simply made paintings with book titles. Creating redesigned covers of sorts, Chong poses questions about the forms of paintings and books. Sans text, the paintings are abstract, playing with the history of abstraction and covering a range of international styles and art-historical moments. They are legible as paintings on canvas, yet the titles of the books — One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Possibility of an Island, Ulysses, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle — are recognizable as important literature, also spanning continents and moments of historical significance. Authorship is stretched in this project, as the book titles carry the names of their authors below them. They are works attributed to Chong that are also “signed” with the names of the writers referenced on the face of the painting. The combination of text and painting makes it so that the works are neither: the titles reference book covers, which they are not, and the paint on canvas fluctuates between art and design. This dangerous combination makes the paintings operate in an uncomfortably liminal space; they are technically paintings, but they extend into a conversation of books as objects, painting as design, design as art, and the imbalanced relationships between text and image.

The paintings without the text might be good as standalone paintings, or maybe they are just passable, but they are primarily decipherable through the prism of language. The painting slips into the realm of design, flirting closely with the historically radical and political motives behind abstraction’s turn to the decorative. The text then becomes a caption for the painting, an instruction for its reading. Not totally relegated to the background, the painting can also inform the content of book to which the title refers. Yet the text in its entirety is also absent from the work; Chong not only empties out painting, but also literature as potentially decorative, i.e. displayed or engaged to signify intelligence. By putting painting into conversation with book covers, the modes of packaging and presenting books, as well as art, become central. The market appeal of book covers, meant to evoke something about the content, but also be attractive to the consumer, ignites a critical commentary about contemporary art production and abstraction in painting. Chong asks us to examine the differences between the two forms, their production and distribution, in a cultural marketplace perhaps not as divergent as we might imagine. With Version (Covers), it is difficult to avoid evoking the overused adage: you can’t judge a book by its cover. Which in this case, raises questions regarding judgment and taste in contemporary culture.

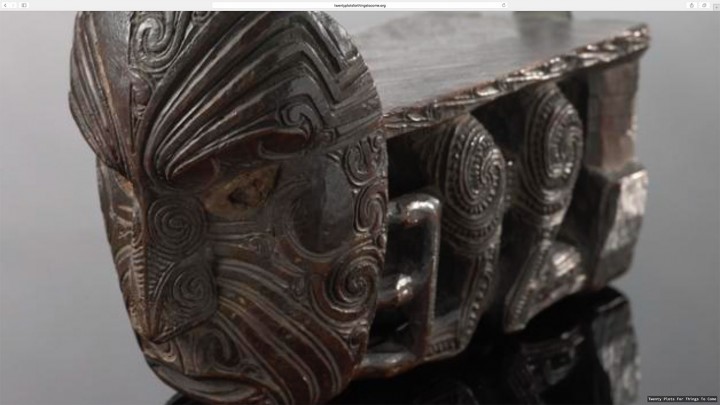

Continuing to examine structures for the presentation of cultural content as information, Chong has culled the online archives of numerous museum databases for a collaborative video made with artist Anthony Marcellini. Twenty Plots for Things to Come (2013) was made by creating an aggregate of around one thousand images: the video is comprised of links to the particular page selected, newly displaying them as images without their original context. The artists will not update the links for the video, so that over time, the video will be increasingly populated with dead links, revealing the impermanency of the web and functioning as a disappearing portrait of a part of the web during the time the work was made. Twenty disparate dystopian narratives composed by the artists accompany this streaming collection of museum-made images. As in much of Chong’s work, the video can be experienced in multiple sites: it is available online, existing as a potentially unending artwork available on the media that it is derived from, but it can also be viewed in a physical space in an exhibition context. Even though the work is composed of museum-made images, Chong and Marcellini don’t privilege the physicality of institutional space.

The amount of information in Twenty Plots becomes disjointed and overwhelming. This portrait of virtual noise is contrasted with the places that house objects of antiquity and perceived importance: places where histories are created and kept. In Twenty Plots, one of the narratives laments the stupidity of the human race over the opposition surrounding gay marriage. It’s just one example of a moment within an archival continuum, impossible to grasp in its entirety. The work is aware of its datedness and the shifting functionality of databases with the emergence of digital tools. That the links disappear speaks to the impermanence of the purported legacy-building intentions of brick-and-mortar institutions — or at least in their online forays. The work captures these early impulses to make everything and anything accessible.

The deconstruction of institutional language also occurs in Chong’s commission for the Asia Pacific Triennial 7 in Brisbane, Australia. Charged with working with the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art’s archive, Chong doesn’t represent digestible information, but presents the impossibility of easily consumed facts and figures. Anecdotes, narrative and tidbits of history dissolve into an audio loop of 85,000 terms and phrases that Chong perceived as being commonly used to define art made in the massive region of Asia and the Pacific. Instead of choosing source material for culling terms, Chong asked museum employees to send him the texts they were reading, adding institutional topicality to the research. Visitors encountered a room filled with red light, with an entrance broken through the drywall. Inside this sinister opening, a woman’s voice could be heard reciting words like: paradise, underdeveloped and overpopulated. The abstraction of language creates an unsettling effect. The tedium of an institution’s archive turns into a work of unclear origins or conclusiveness. Something relatively banal, like the archives of a museum, becomes content fueling a post-apocalyptic chamber. Without knowing the origin of the audio, we might wonder what these terms, adjectives and qualifiers refer to, reaching an intentionally exaggerated space of fantasy that reaches far beyond the realities of local art production, but also emphasizing the persistent exoticization of language used to describe the arts in the region.

The exploration of vessels of cultural expression continues in a recent exhibition by Chong this year at the Art Sonje Center in Seoul, Korea. “Never, A Dull Moment” is inspired by a short story that Chong wanted to write about a non-profit space going through a mid-life crisis. With lines in the gallery guide such as: I can’t do this any longer, it typed a Whatsapp message to a commercial gallery, with whom it had been having an on/off affair with. Don’t be silly, the gallery replied. Take a beach vacation, get drunk on cocktails and everything will be fine. Can you come over now, I miss you, the space typed. No, I am sorry I can’t, the gallery replied, I have an opening tonight, remember?

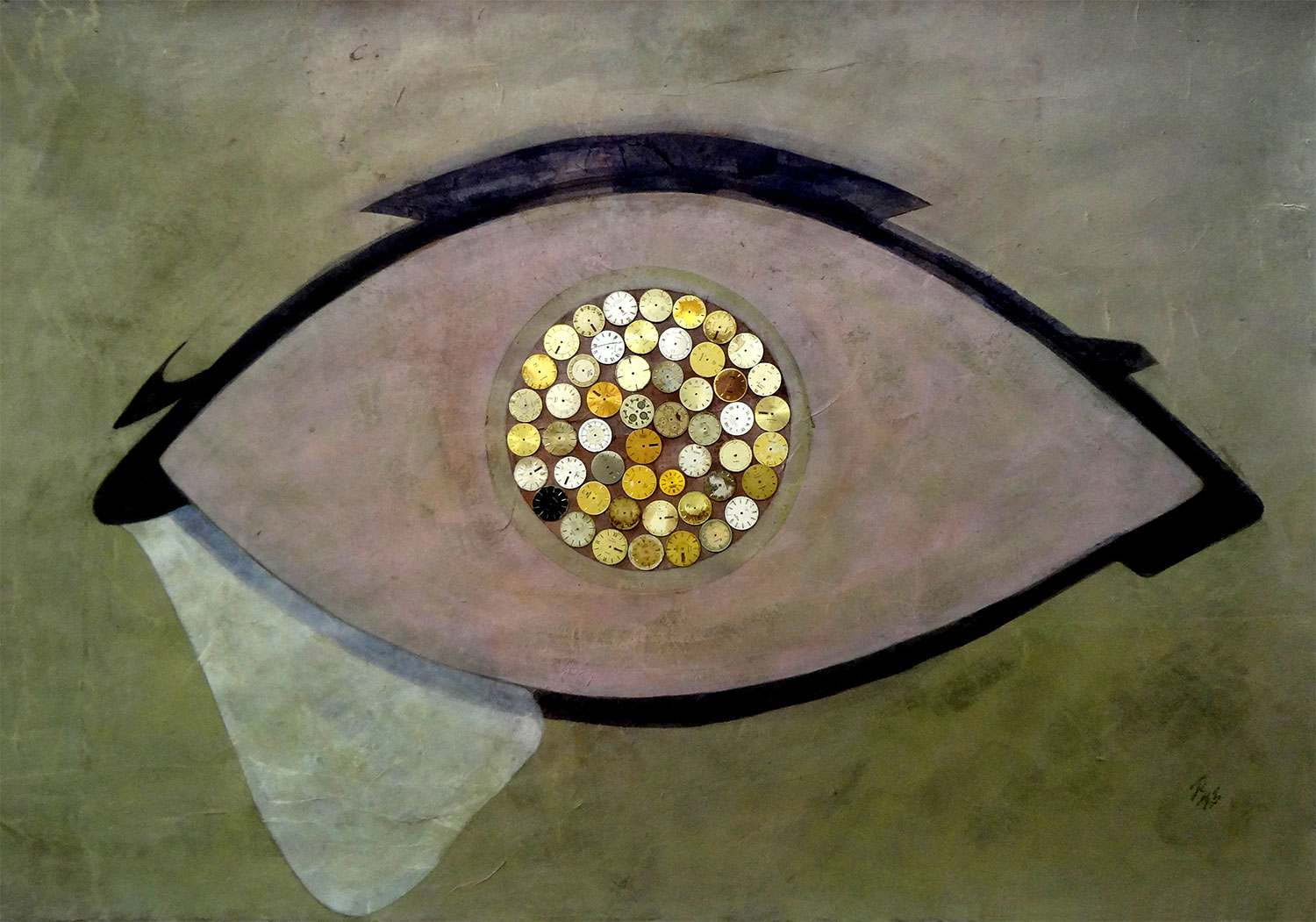

The narrative accompanying the exhibition explores the shifting dynamics between different exhibition spaces, a reconfigured story that Chong incorporates into the objects on view. Here, tellingly, the non-profit is increasingly in crisis, while the gallery is depicted as a cool distant lover too busy for the needy non-profit. Works in the show fold in modes for viewing contemporary art. Noting that guests to openings often mingle outside smoking instead of lingering in the interior space of the exhibition, Chong has created a new work composed of two ashtrays, effectively creating a smoking corner called Smoke gets in (your eyes), eliminating the need to leave the show. An older work, Until the End of the World (Paused) (2008), plays the 1991 Wim Wenders’ science-fiction film until the first person enters the exhibition, marking the moment when the film will be paused. The film then becomes a still within the space for the duration of the day. This work is contingent on attendance to the show, further incorporating the habits of viewers into the show. Boiling Point is another new work that features two identical pots filled with water that eventually come to a boil, suggesting a cycle of constant maintenance (boiling, evaporating, refilling). Within, You Remain is a work comprised of the debris and trash from the de-installation of the previous exhibition, and an ongoing instruction to the staff not to clean the floor. Witnessing the usually disposed of scraps from the previous show, visitors are reminded of the continuous turnover in the space; they are also tacitly invited to collaborate, as visitors reposition the trash through their movements.

This exhibition, like much of Chong’s work, incorporates the structures and conventions of contemporary art viewing and reception, combining them with popular narrative forms like film and novels. The removal or reordering of information becomes part of a sinister drama. The back cover of Philip reads: Meanwhile, listening to disaster reports on Channel 23Ω, Cassandra has a vision — a new world glimpsed through a tear in the fabric of reality. Will there be Rapture or Revolution? And does history, like all stories, ultimately have an end? These questions extend through Chong’s oeuvre; the narrative devices he employs to tease out assumptions and latent aspects of culture industries point to “a tear in the fabric of reality.” We are left to wonder whether these are just new fictions that the artist has created, or if there is more truth to them.