It was a warm, summer evening in New York, and I found myself dining outdoors with a group of artists, mostly young men, who were speaking in a quick, witty clip about an endless stream of tenuously connected things. There was talk of early Black Sabbath albums; John Lurie’s cult TV series Fishing with John; little-known, reclusive painters; and beer. Among the group was the artist Rashid Johnson, who slipped in a reference to a television game show entitled Know Your Heritage. And no one knew the reference but me. It’s not that I had spent that many more hours than everyone else combing the web for odd bits of esoterica; it’s just that I grew up in the same place at the same time as Rashid Johnson and was familiar with the Chicago-based quiz show that aired every Saturday in February — Black History Month — and tested local high school students on their knowledge of black history.

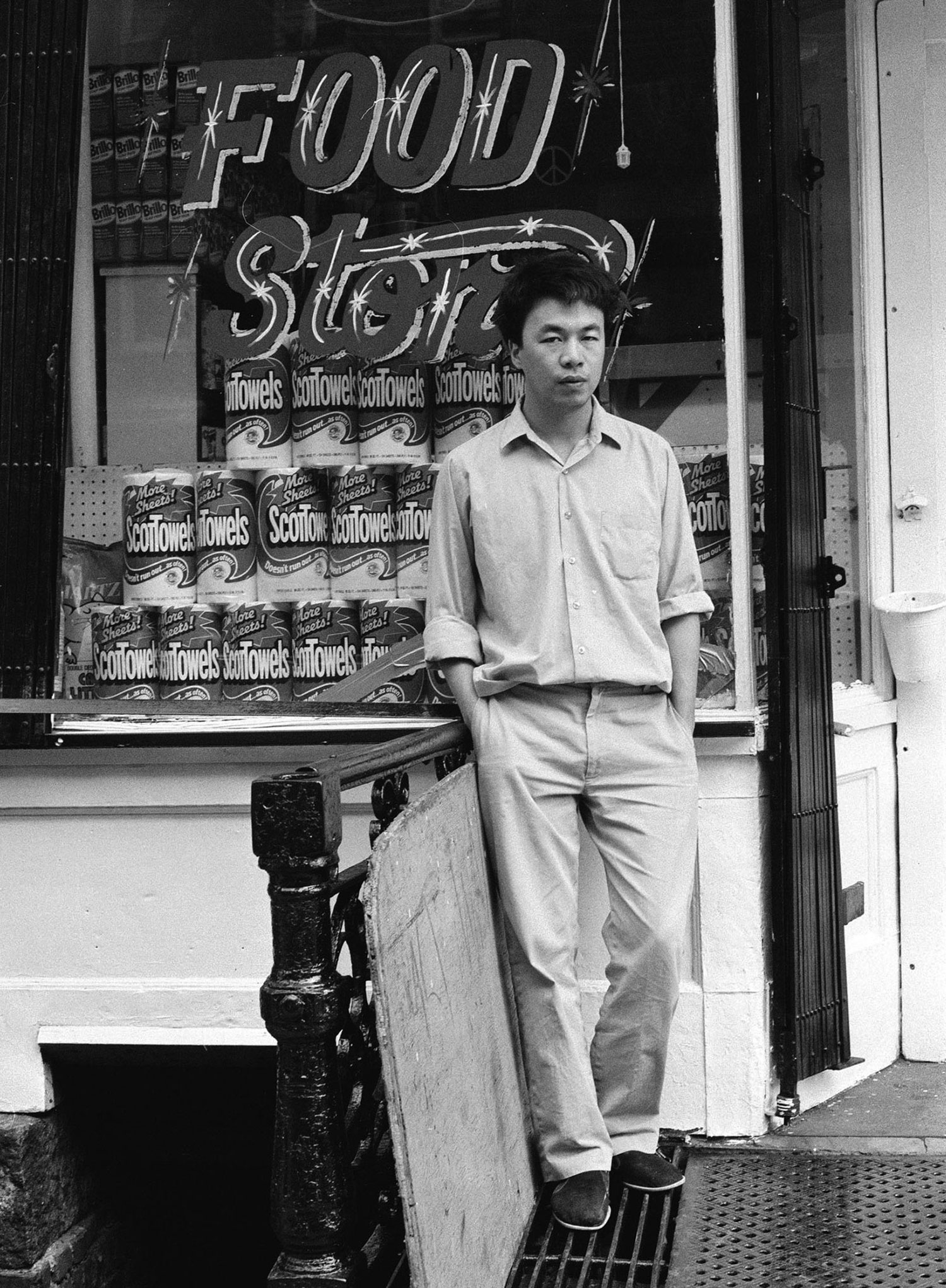

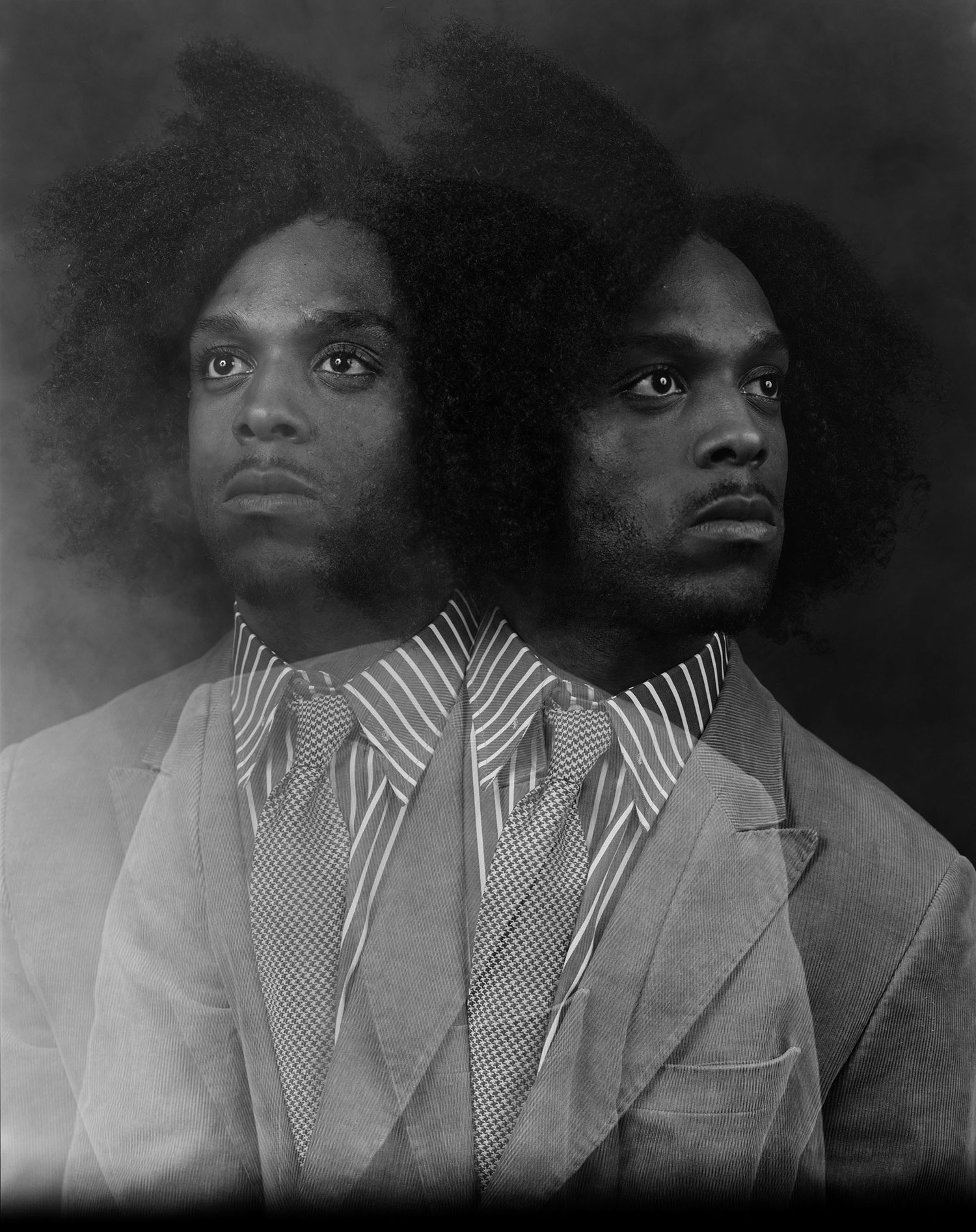

Born in the decade following the Black Power movement, when there was a sense of social urgency for black people to have knowledge of and pride in black achievements in the United States, I knew most answers to the game show questions and took black history for granted as a basic part of my cultural and formal education. I suspect Rashid Johnson — also a post-Black-Power child with a mind ripe for esoterica — knew most of the answers as well. Indeed, Johnson speaks rather openly about his parents’ ’70s-era Afro-centrism leading to his own informal education in black history, and it’s clear that an early engagement with these historical narratives heavily informs Johnson’s interdisciplinary practice. Initially trained in photography in the late ’90s, one of Johnson’s earliest works is a portrait series that features homeless black subjects — a very early gauntlet thrown down to the tradition of who, in terms of race and class, is assumed to be a worthy subject of a fine-art portrait — and later photo series referenced black historical subjects like the very heroes we would be quizzed about on Know Your Heritage such as Thurgood Marshall, Emmett Till and W.E.B. DuBois.

These later series also took on the singular quality of using contemporary subjects such as models, friends or even the artist as stand-ins for these historic figures. In these photos, Johnson goes into a completely subjective mode of representation so that a responsibility toward historical accuracy is kept at arms length and his contemporary community appears equally visible as a subject. By the time Johnson creates the series “New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club,” fantasy and fiction wholly provide conceptual structure for the photographic project, and history is an aesthetic exercise. In all of the photo projects, Johnson often used arcane processing techniques or anachronistic staging to lend the works an “aged” patina. Thus Johnson is seen very early on taking up the symbols, tropes and subject of “history,” only to turn it on its head as a foil for an immediate, contemporary condition. Johnson’s work soon moved into other media, namely text works, sculptural objects and painting, while often returning to photography in many guises. A precocious early sculpture is a John McCracken-esque plexiglas plank filled with the hair product commonly known as “pink lotion.” The joke being that pink lotion, long used to give sheen to black hair, now lent an art object the post-minimalist sheen of a Finish Fetish work. Johnson works fluidly with text, and in 2004 he created Death is Golden by “writing” that phrase in gold spray paint on paper as a literal pun, a wry take on “street art,” and a sly reference to Paul Beatty’s historically possible but implausible anti-hero Gunnar Kaufman, who in the 1996 novel White Boy Shuffle unintentionally advocates mass suicide for black people.

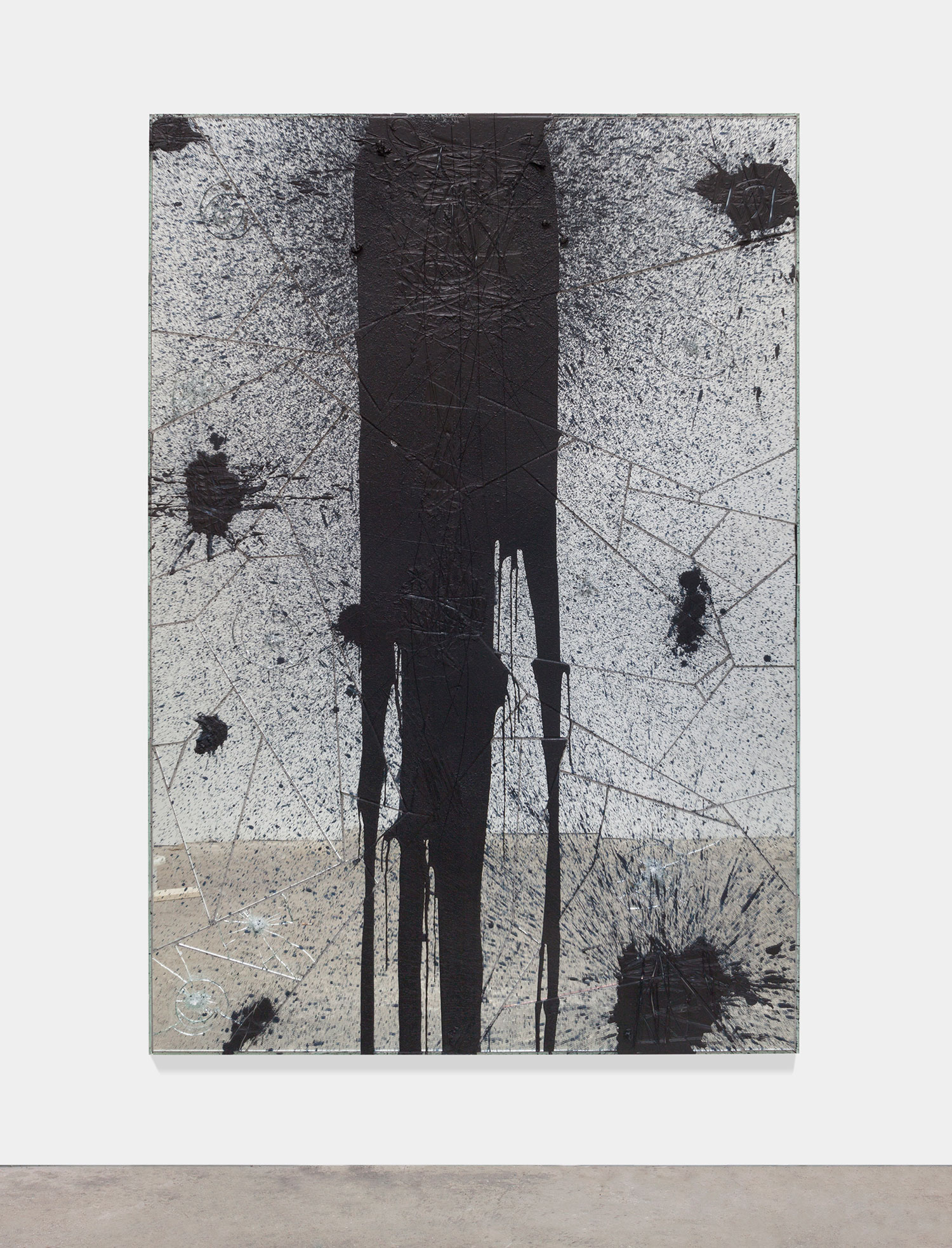

Johnson came into art-world prominence with his “shelves,” post-minimalist sculptural objects that are distinct as their own forms yet also as physical supports for an assemblage of disparate objects such as books, plants, glyphs, albums and incense. In a manner similar to Marcel Broodthaers’s way of using common objects as stand-ins for cultural identity, the shelves feel like fetishes from the Afro-centric late ’70s, when Johnson was born. The shelves are a study in order balanced with chaos. Some shelves are created with cut mirrored glass, adhered in a gridded, tile-like fashion, with the occasional black splotch dripping down the surface. However, the earliest shelves were framed from wood and over-painted with a mixture of black soap and black wax, acting as a painting as well as an assemblage. Painting is a core language for Johnson, who has contended with the traditions of the monochrome and expressionism since his student years. His ongoing “Cosmic Slop” paintings are the technical precursors to the shelves as the first objects to utilize the black soap and wax pigment, a material that conveys Johnson’s painterly gestures — the pouring, pressing and splattering of the pigment — and sometimes his symbolic markings. Materially, the “Cosmic Slop” works are a form of encaustic: a technique created in ancient Egypt that harkens, in more contemporary form, to Jasper Johns’s iconic proto-pop works. Incredibly cryptic, the paintings signal expressionism but also contain ideograms that suggest the channeling of a message from a lost (or future?) civilization whose language we have yet to decode.

All the above works demonstrate how Johnson selects as his sources the history, lore and material culture of black America and wraps them within the form and techniques of art history — much in the same way that David Hammons — whose work Johnson often references — often creates art objects from the material and cultural habits of his Harlem vicinity. Rashid Johnson’s use of historical references are often read as a historical reckoning; at times, Johnson feeds into those slightly activist readings that consider his work an attempt to complicate perceptions of black history and African-American class dynamics. That concern, however, is engendered more by audience reception — a reception already primed by a steady diet of stereotyping, media images and pessimism toward black males. This desire toward complexity is an oft-seen concern among artists of color, and it peaked especially during the heyday of identity politics when Johnson was studying art. That drive toward complexity also follows from an instinctual sense that artworks are somehow competing with mass-media images, possibly because of the easy way in which pop-culture references find their way into fine art practice.

Yet there is something more complex happening on an aesthetic and conceptual level in Johnson’s work that is seen not in the materials and subjects he chooses, but rather in the way he selects and activates those materials. Consider two important things: many of the materials Johnson selects for his objects are books and music created at the key points in his life or intellectual development, and many of the photographic models he chooses are acquaintances. In other words, Johnson’s works speak to his own personal history and identity formation, not a generic black history. But unlike Mary Kelly, say, who used a social “field notes” format as a way of examining one’s personal (read political) life, Johnson’s reflection eschews the master disciplines of science and narrative, and instead revels in fantasy, or else engenders a set of mental associations with objects as in a surrealist game.

Johnson stands on the somewhat dainty shoulders of an artist such as Karen Kilimnik, who brazenly creates sculptures and installations and paintings in which her own sense of self-value and personal narrative begins to intertwine with mass-media culture by way of objects gathered from her personal space. Kilimnik’s work demonstrates how a contemporary artist’s imagination these days tends to be shaped less by primordial drives and more by one’s relationship to an immediate and material culture. The artist then finds oneself in the position to rework these symbols and material over and over again in a continuous process of absorption and discharge that can take on many shapes and forms — or can be formless, as in the case of both Kilimnik’s and Johnson’s abstract works. When faced with an endless stream of references, the key is to avoid neuroses, usually formed, according to Sigmund Freud, when one suppresses key aspects of one’s identity. I doubt Johnson has any true fear of neurosis, but it is no coincidence that he is interested in a character such as Gunnar Kaufman, who is trying to perform multiple conceptions of his self as a black man. However, I also have no doubt that Johnson is aware that Freud’s model of the subconscious was shaped by the psychoanalyst’s interest in ancient history and Egyptology.

Consider “Shelter,” Johnson’s recent exhibition at the South London Gallery, which takes the Freudian couch as a motif — the couch is multiplied, each covered in zebra skins as if to be Africanized, appearing in several configurations and, at last, standing up as if in Oedipal defiance of its psychoanalyst master. In other words, Johnson’s contemporary mélange of images, ideas, gestures, historical references, materials, friends, family, fact and fiction isn’t about craziness. It simply expresses the contemporary condition in which multiple possibilities and references make up the self. Johnson’s gift is his keen ability to read images and symbols on multiple and unexpected levels. Take, for example, the crosshairs that grace the cover of Johnson’s first monograph [Message to Our Folks, exhibition catalogue, MCA, Chicago]. Long seen as a symbol of gun violence, crosshairs mark out a target for a gun’s shooter. It is also part of the logo for Public Enemy — the hardcore rap group who reigned in the late ’80s and early ’90s with a mix of consciousness-raising calls to arms and the zany antics of its hype man Flava Flav. By appropriating that symbol, Johnson places himself squarely in hip hop’s lineage — a black cultural production that was known for its aggressive stance at the height of the culture wars. Yet in the realm of art history — of which Johnson is clearly a student — the target takes on a different register. It is most often associated with Jasper Johns’s proto-pop encaustic paintings, which I already identified as precursors to Johnson’s painting works. Thus Johnson is making a clever pun that synthesizes the complexity of his cultural references — high and low — into a common symbolic language. And, if Johns’s early painting works were an attempt to make icons appear uncanny, then, in today’s moment, we find Johnson attempting to make the uncanny appear plausible and the indecipherable make perfect sense.