Yongwoo Lee: I would like to start by talking about how we both understand contemporary art as a response to social urgencies and critical demands. We’ve worked together a number of times, but we have not thoroughly discussed our goals and socio-political and artistic influences. This might be because we both understand the circumstances we face at home and abroad and thus share an idea of what art is expected to be. Do you ever try to influence society with your art?

Ai Weiwei: It would not be hard to define the role of art in society, as you say. Art is a living entity, and it breathes in and out through society. Art should be able to speak to social urgency and critical demand not because art is political or social but because it is socially vivid and alive. We can’t take the skin of art as real art.

Like artists, those who understand art are rare. The art circle is not big, and it is not expanding to a great extent. I have been trying to find new trends and possibilities by communicating through the Internet. That is how I became “Ai Weiwei,” since it is not quite possible for me to show works in the galleries here in China, and mentioning my name in the newspapers or on the Internet in China is almost impossible. I joke that if someone took a photo of my back and put it on the Chinese website Weibo, they would be identified by the government. I am sure they would. It is very interesting. It becomes a metaphor — you see how today’s society is afraid of images. Why do certain things need to be deleted? So people start to make arguments saying that they do not support me or understand what I am saying, or even care. But they will keep asking: Why can’t this guy be on the Internet? Of course, nobody will answer questions like that, so the question will remain. So I always want to keep in mind the new potential of the Internet, and so far I think it’s very successful. But at the same time, it brings me so much trouble because it’s influential and bigger than me. It starts to hate you and think you’re terrible.

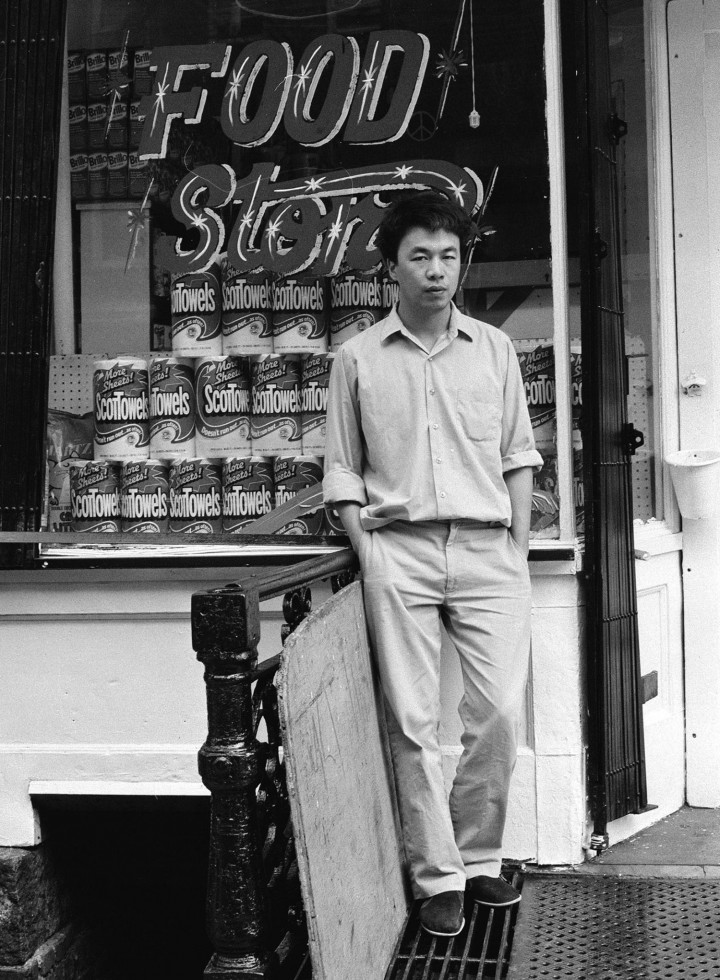

YL: You lived in New York for twelve years, from 1981 to 1993. How did you find China had changed during the twelve years of your absence? How has China changed in the twenty years during which you have been in Beijing?

AW: I think the main differences in Chinese society, in relation to me, have involved a person—his name is Ai Weiwei. He is determined to make a change in society and he has almost realized this. I try to be a real part of the new Internet generation. Yongwoo, we are from a slightly older generation, but we are still a part of the Internet generation. We are making some differences through this very essential exchange of information.

YL: Since your return to China, do you believe that you are making a real change in Chinese society through the Internet? Do you also believe in an electronic democracy?

AW: I try to act on very detailed and specific matters that can easily involve anyone, and in which any belief can be either right or wrong, false or true, real or fake. We spend so much time on the Internet every day, and we see the world start to change. People are freer because they can access information easily. They have a more balanced view and thus can make independent judgments and choices. So all of this is happening, and that’s the change. Another change is that China has become wealthier. This may have produced an unbalanced society in many ways. The environmental issues and corruption scandals have become problematic on every level. Imbalanced wealth destroys education and produces many other issues. Many crises come about through unexpected developments.

YL: What are your thoughts on censorship and the control of information in China? Is it still strict or has it gotten better? Have you ever considered the government’s position?

AW: In China, there are policies that control the flow of information. There’s a big department called the Propaganda Department that belongs to the Party. I realized that neither the media nor individuals could even find the name “Ai Weiwei” or any articles about him. Not even those that criticize me, because the name itself is forbidden. So there are no articles criticizing me, which is very strange. After sixty years of being established in this nation, they have accused me of tax fraud, and these are just simple words, right? If somebody crashes a car or steals something, nobody writes anything about it, but this is considered a major crime. From my example, you can see how cleanly they control the flow of information. The censorship is strong. There are 100,000 or so “internet police” who are online just to delete or twist information. But still China is sending out hundreds of thousands of students to study abroad. Last year they sent nearly 170,000 high school students from private families. In 2005, they only sent 65,000 students to the United States.

YL: Once you told me about your childhood and the relationship you had with your father, Ai Qing, the revered poet, and especially his isolation by the Beijing authorities. Do you think this incident influenced your own relationship with China?

AW: My father studied studio art in Paris. He was a very good artist, and if he had continued he would have been one of the best artists in China. Many artists who were of the same generation as him know he was a good artist. But after he came back home, he was put in jail where he became a poet. So he became a very famous poet. He influenced me; I feel like there are inherited values. They hardened me and engaged me with political struggles since I was born in such a politically turbulent period.

YL: What kinds of political upheavals were there?

AW: I see how wise my father was. He loved art and poetry during a difficult period of his life. I am sure it would have helped him in the most difficult time. This influenced my siblings and me during our childhood. I can also see how he had been able to survive the difficult situation of having to clean public toilets. He was forced to clean public toilets — a lot, not just one. There were about thirty of them in a rural area, a very poor area. I remember it was very messy.

YL: Where was it? In the remote countryside?

AW: It was. He did the job well. In the beginning, we were ashamed of our father’s job, cleaning toilets for 205 days a year. He said to us, “You know, I am sixty years old. I didn’t know who cleaned my toilet before.” He is a man who does his work very well. He had never performed any physical chores before, since he was a scholar. But he made such an effort to make every place so clean, to put dry sand on it, to clean all the corners. He made a very clean, very fresh environment of the toilets. Tissue is a new invention — back then there were no proper materials for people to clean themselves. They couldn’t even use outdated newspapers since Chairman Mao’s slogan was published on the cover. If you had used the newspapers, it would have been considered a counter-revolutionary act. I grew up in a very absurd society. I haven’t discussed my family or my father often — in a way I wanted to cut their narratives off from my own life. When I was arrested, I thought that their stories might still be helping me through dark times and experiences. My father was also in a jail for years and was very outspoken.

YL: That’s an impressive and touching story. Let’s change our subject to art again. Your presence in Europe at the Venice Biennale in 1999 and at Documenta 12 was influential. But Sunflower Seeds at the Tate Modern in 2010 earned such a strong and immediate response. What explanation can you give for this success? Do you consider yourself a famous artist?

AW: I believe I am popular, but I think my popularity is strange. People talk about how popular I am. I read about myself in the papers all the time, but it’s not real to me. I try to stay out of it. When I walk out of the studio I have to check if anyone is following me, and if I take my kid to the park, I think someone might be in the bushes taking photos of me, particularly the secret police. It is absurd. In China, my name cannot be mentioned, but when I walk down the street sometimes young people come and ask to take a photo or they shake hands with me and say they are supporting me. That kind of popularity may exist in Asia to a certain extent, but it is mainly from the States. I often tell the police, “You guys should not do this, because it will make me more famous.” I am too famous, and I am always in the news. I’m supposed to be just an artist, doing my work. I’m not even a good artist. I’m just an artist.

YL: Did you say you are not a good artist? What defines a good artist or a bad artist?

AW: I don’t know what a good artist is. I don’t know if it’s lucky or unlucky this way. I believe that there are all kinds of jobs, activities or practices, but art is the only thing that is everywhere. Art is really able to form a dialogue and connect different parts of society.

I like to play with dense information or stimuli. Playing only one role for me is too narrow. I would like to play different positions. Being aware of the total situation is what made me who I am today. I follow dense information and varied actions.

YL: An interesting aspect of your work is that it has developed as part of architecture and design, for example your collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron to build the stadium and with Norman Foster on the expansion of Beijing’s airport. It was also through architecture and design that our collaboration on the Gwangju Biennale began, where you became co-director of the design segment in 2011 and created the Gwangju Folly Project, co-curated with Seung H-Sang. How did you find our method of working when we teamed up? And how was your first experience directing a biennial?

AW: Norman Foster, for example, I didn’t know very well. I only recorded his project with photographs. But to me that was an important process because nobody does it. When I proposed that I’d like to photograph the whole thing, he was quite surprised. His art is closely related to photographs, and he said it is a good idea. We needed his support to get into those sites because it had military-like security. Each time we went they had to open the door for us; they were really supportive.

Even the stadium, which I did in collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron from start to finish, I’m sure nobody wanted to record. So many opportunities are out there, many things that can be done from any direction. It’s very interesting to me that people always rush in one direction without any care. You know, you don’t have to make an effort; if you can just stand still, you can make progress all the same. You don’t have to rush. But nobody believes that. They all seem to rush in one direction. It’s hard to tell young people this, because education ruins it by saying everyone has to rush and rush and you will get somewhere. The problem is that people have no patience. As Kafka said, impatience is a sin. So when we started designing, I thought it would be better to record the process of building the stadium. The stadium will be seen by everyone, but nobody knows or maybe even cares about how it was built. So we recorded honestly, sending people out to photograph the progress. We came up with a set of… maybe we call them artworks. They are just honest recordings. When you put honesty into art, they call you an activist.

YL: Some have noted that part of your work reflects the artistic purity of the Chinese tradition and its rigorous values, yet it also calls for multiple readings as it references challenging and pressing social issues. How do you see the relationship between these two different aspects of your work?

AW: I think if we consider the different subjects of art, on one hand art is about our memories and on the other it is about our dreams. With our memories we try to figure out who we are and where we come from. With our dreams we try to achieve a state that overcomes what we are not satisfied with today. So contemporary art is not simple; it’s about understanding how we think — our human sensitivity or intelligence — and coming up with some kind of manifesto. You know, every work has a manifesto. I think that’s how I would describe it.

YL: What I meant to say is that many of your works are closely related to the traditions of China, like the porcelain and the furniture.

AW: I am very fascinated by our nation’s behavior. I think that all works of art here are the product of a so-called material culture, its aesthetics and moral stance. It’s fascinating, the life and history of this culture, how its people survived ups and downs, and how different they are from the rest of the world. I think you only learn about something by working with it, so I started collecting works. I started taking them apart and putting them back together, arranging them in new ways to try to interpret them with their own logic but using contemporary forms. Some of my works are quite casual.

YL: At this year’s Venice Biennale you have been invited, together with three other artists, to be part of the German Pavilion curated by Susanne Gaensheimer. Can you tell us about the project?

AW: We are four artists showing in the German pavilion. Not at the actual location, but at the French pavilion. One is German, but the other two are probably not of German nationality. Two artists are photographers, very interesting. The curator asked me to do an installation, so I worked with traditional subjects again and made one large-sized installation, a new work.

YL: I was told that the German and French commissioners have decided to swap their pavilions.

AW: I don’t know very much yet but I think it’s a good idea. I think that using the concept of nationality is somewhat outdated and that national pavilions are an old idea. Maybe they can just appoint a national curator for the organization of the show, but even that may not be necessary.

YL: I understand that you still have travel restrictions. What about the opening of your two upcoming projects? You could send someone to be in charge, such as an assistant or one of your family members.

AW: I will have to think about it. The police won’t allow me to leave the country. I could try to make a bargain with them: “If they allow me to go, I’ll be quiet. If not, I’ll make some noise.”

YL: Alongside the Biennale there is your other project at the Giudecca. Can you tell us about this?

AW: This project is very sensitive. It will be about my detention. Everybody wanted to know what happened to me during my 81 days in custody. I can’t address sensitive issues in the German Pavilion. If I don’t reveal what happened to me, I will have to face many questions. I am preparing six boxes in a church at the Giudecca. Organizers will have to prepare for any challenges that may arise. I can’t reveal more.

YL: What will be the next project we work on together besides the Biennale?

AW: There are a few projects in the United States and Europe that are currently under discussion. They will be clarified soon.