In a display of both bravura and spectacle, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) launched its grand opening last November 5, presenting to the art world what promises to be China’s largest and most comprehensive contemporary art center.

Beijing rarely sees the likes of such a well-heeled crowd, which included contemporary art stars, the ‘hottest’ curators and, naturally, elite friends and associates of the UCCA founders and Belgian collectors Guy and Myriam Ullens. A crucial platform for world-class exhibitions, events, educational and public programs on contemporary art, UCCA is located in the art hub of Beijing’s 798 Arts District and occupies a massive 8000-square-meter former electronics factory that has been sleekly redesigned by French architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte in partnership with local architect Ma Qingyun. The airy, light-filled spaces house three exhibition halls, a library/research center, café, gift shop, auditorium and screening rooms. Despite the fact that supporters Guy and Myriam Ullens are owners of a world-renowned collection of contemporary Chinese art, UCCA has no plans to move the collection to China or to feature a permanent display. This choice against vanity seems wisely intended to stress curatorial independence and emphasize UCCA’s nonprofit status among a sea of commercially run, ethically fraught art spaces in Beijing and China in general.

In a nation of ‘firsts,’ one is never enough. UCCA, the ‘first’ major nonprofit contemporary art center in China, unveiled their sparkling renovation simultaneously with “’85 New Wave,” the ‘first’ historical survey of those explosive and formative years of contemporary art in China.

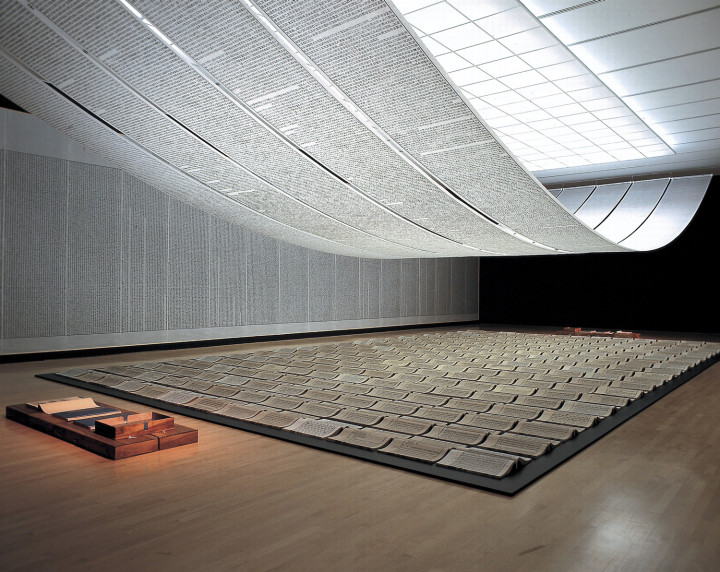

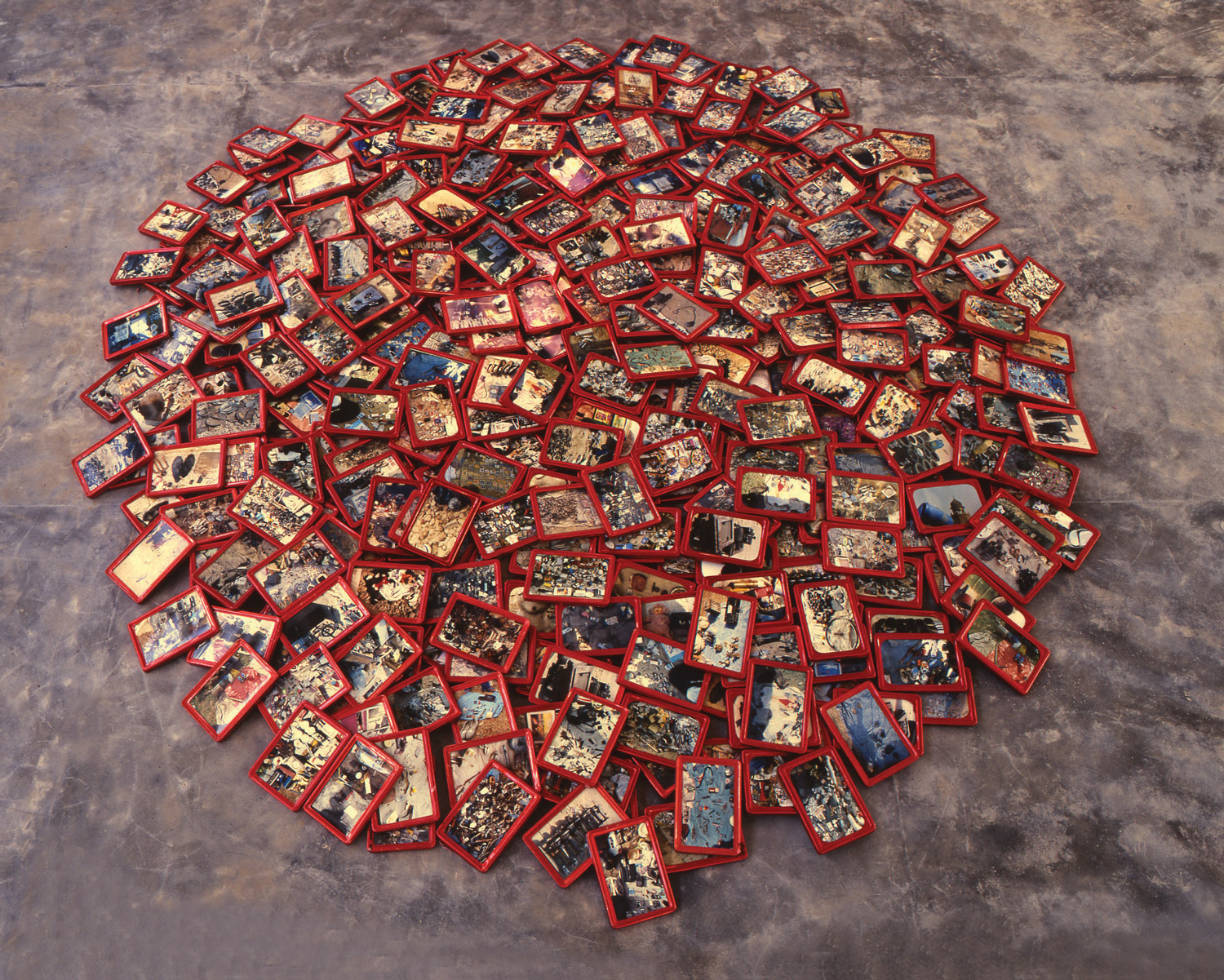

The model of the historical survey exhibition may be an outmoded form, but in the context of China’s current fascination with the market, revisiting the past while embarking into the future is a necessary task. UCCA artistic director and exhibition curator Fei Dawei presented over 100 works by 30 artists borrowed from public and private collections and supported by works in the hands of the Ullens themselves, in a solemn, if somewhat bland attempt to capture the heady idealism and experimentation that defined the era. Stark monochromatic canvases by Shu Qun, Wang Guangyi, Geng Jianyi and Zhang Peili remain fresh; intimate abstract works by Ding Yi and Yu Youhan nicely offset large-scale installations by Wu Shanzhuan and works recreated on-site by Huang Yongping and Gu Dexin (both originally conceived for the 1989 “Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition) are an unusual treat. The rare opportunity to see these works together for the first time might outweigh the notable absences (Ding Fang) and questionable inclusions (Chen Zhen, Yang Jiechang); yet one yearns for a more defined framework through which to access their undisputed significance.

Transported from its messy, vanguard beginnings to a ‘proper’ white-box museum setting, “’85 New Wave” is a landmark show, signaling the tension that goes with the conflicting process of contextualization and canonization of Chinese contemporary art while striving to remain true to the radical and experimental gestures within.