Kader Attia, the artist who co-directed this year’s edition of the Berlin Biennale, has placed repair as a strategy at the center of his own practice, and his artworks often enough make that concept literal. For “Still Present!” he decided to turn it back into a metaphor. Co- curated by Attia, Ana Teixeira Pinto, Đỗ Tường Linh, Marie Helene Pereira, Noam Segal, and Rasha Salti, the exhibition intends to heal the wounds of Western overproduction and — ironically — the profusion of sprawling monumental exhibitions.

Modernity has imposed its regime on all aspects of life, and it has created what the reappearing wall text refers to as a planetary emergency. It is a flawed and failed project that has resulted in multifaceted trauma, be it colonial, ecological, or otherwise. The curation relies on the works to carry this theme, and the pieces require focus and concentration, as if to assert their own seriousness. For example, Les Gorgan (1995–2015), Mathieu Pernot’s series of photographs of a Roma family in France, which culminates in a touching film, is shown in a thoroughfare in the cavernous gallery at KW where few people pause longer than a minute — one of the curatorial decisions that make this venue feel stifling and overcrowded.

A large part of the show leans toward the documentary. At Akademie der Künste, Lamia Joreige’s After the River (2016) portrays Beirut, its complex history and its gentrification. There is also Susan Schuppli’s eerie video series Cold Cases (2021–22) that speaks of indigenous land rights and police violence in North America, or the group DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Research – Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti), who look at Italian fascist architecture in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

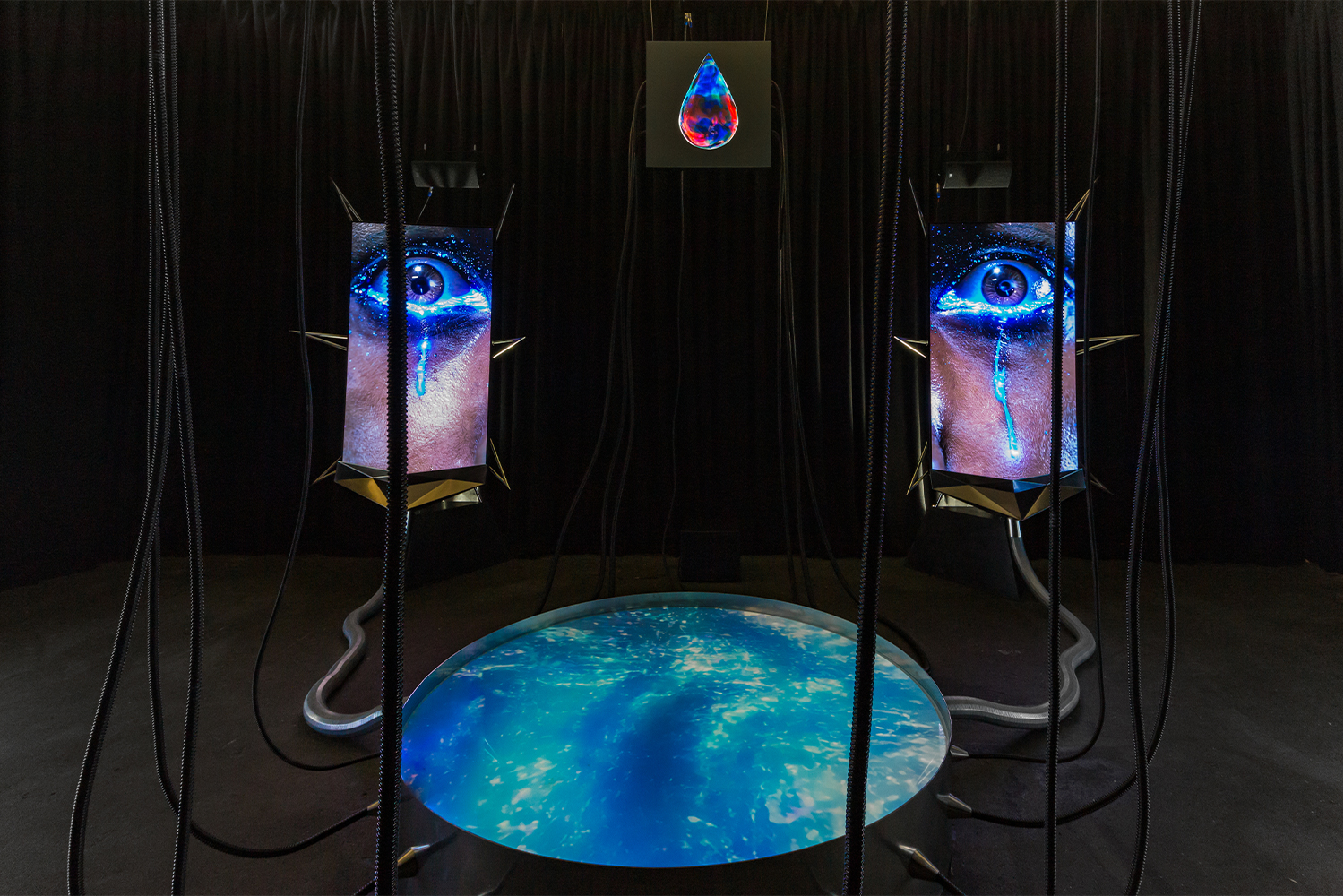

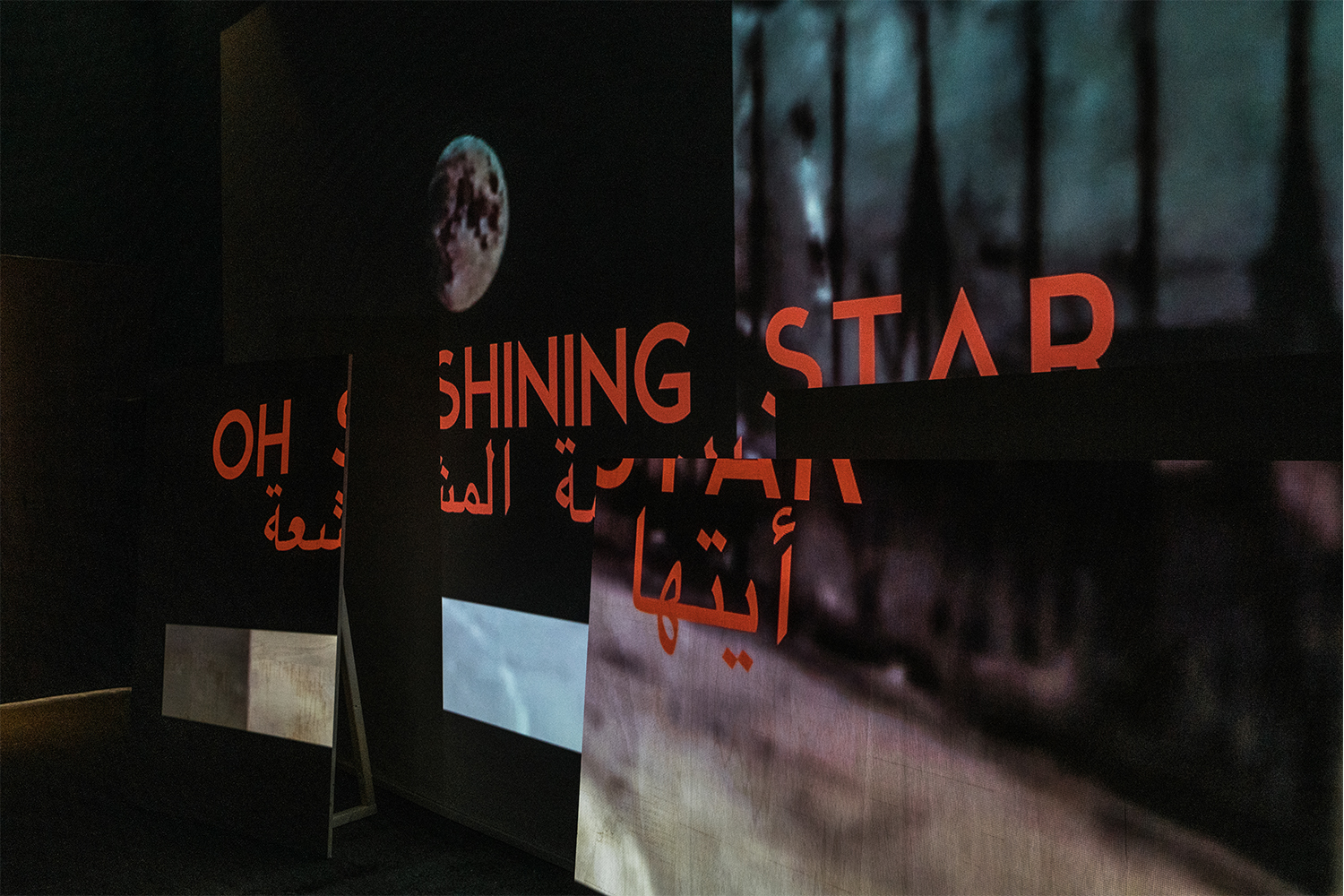

Works that deal with the digital are conspicuously absent from the show, except for Zach Blas’s oddly monumental ten-channel video installation, which occupies an entire room at Hamburger Bahnhof, and the darkly psychedelic The Moon Also Rises (2022) by Yuyan Wang. Both would have been right at home in the DIS- curated 2016 edition of the biennial. This year, after the Real has exerted its revenge in the form of a worldwide virus that forced us to rethink supply chains and the economy, which will never move entirely to the digital sphere, it also comes bursting back into art institutions. In Berlin, it does so in the form of videos that purport to show unmediated reality, often without an authoritative voice-over.

The curatorial statement constructs a uniform modernity as adversary. Many of the works increase the complexity of this antagonism: take Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). The four-channel video speaks about the children of Senegalese s

oldiers who served in the French army in Indochina — a story of hybrid identities and interlacing histories.

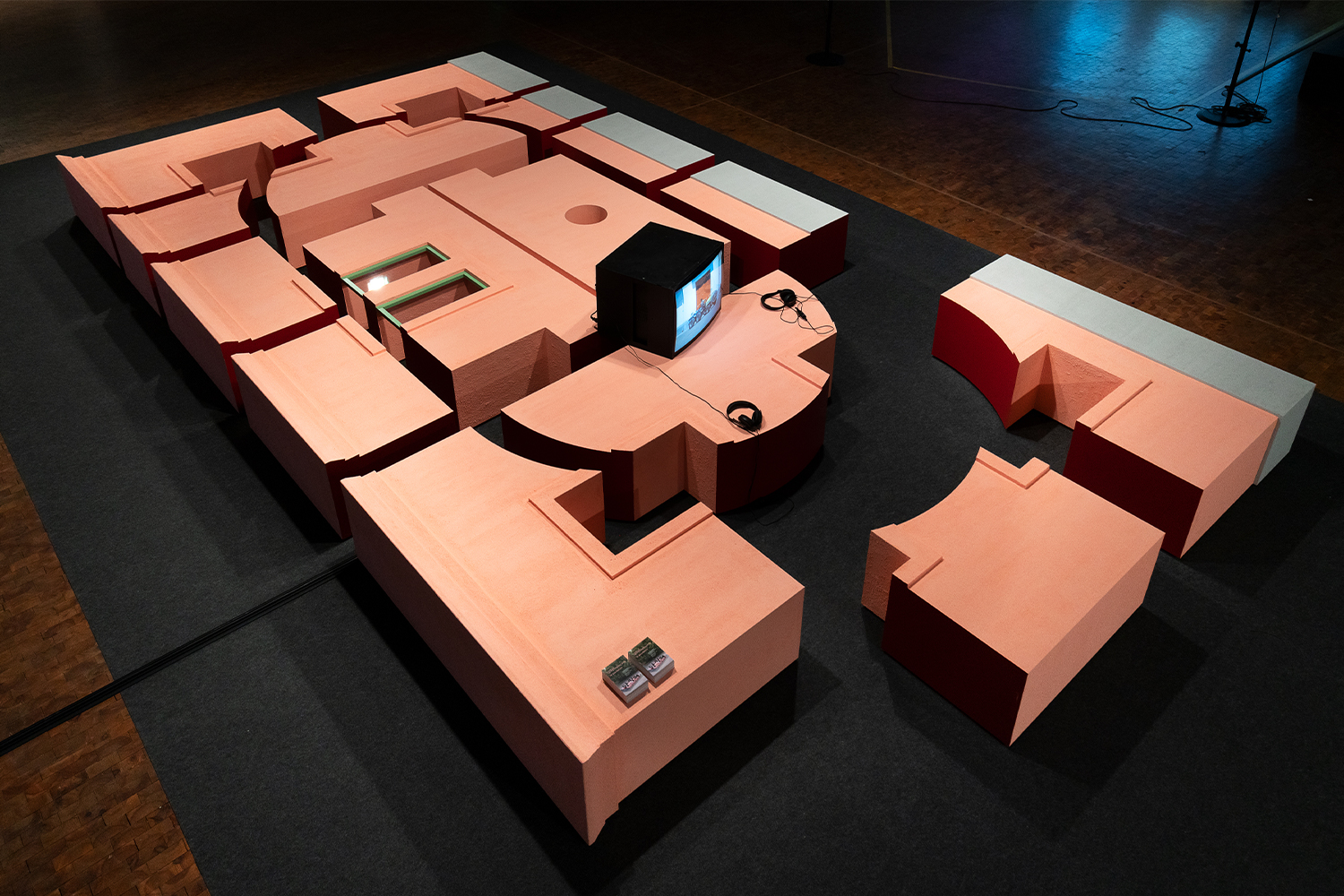

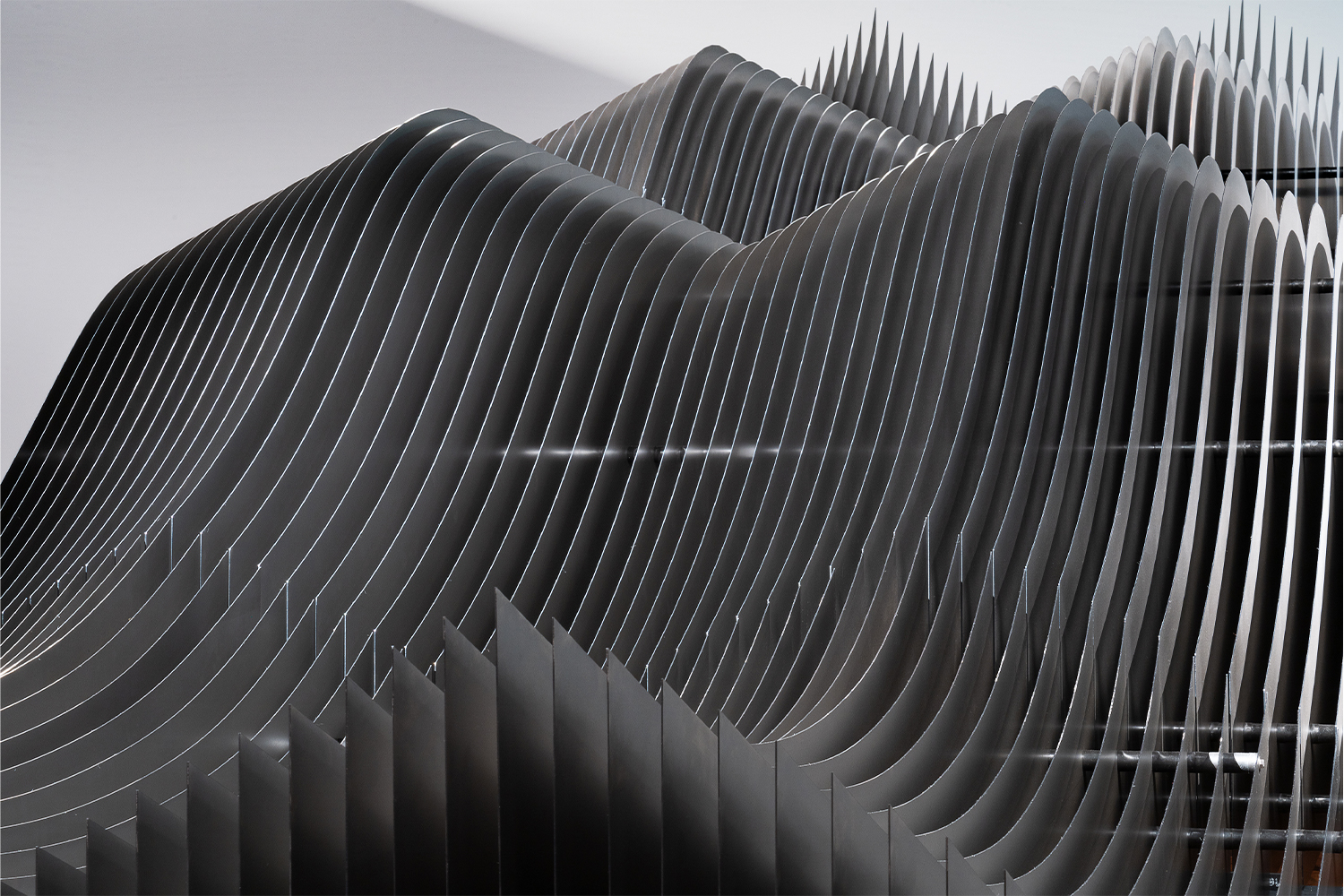

The section near the Brandenburg Gate strays from the documentary. Moses März’s large-scale mind maps, which are suspended from the ceiling, trace postcolonialism in the Eastern Bloc, as well as the way decolonial movements interlace with the work of African-German Enlightenment philosopher Anton Wilhelm Amo. This semantic machine is complicated, granted, but it is self-aware enough to avoid jargon. Instead, the drawings on textile exude a gentle poetry. Next door, Khandakar Ohida’s Dream Your Museum (2022), which perhaps acts as a central piece in this venue, is projected in a lofty hall. The work tells the story of the artist’s uncle, who has amassed objects in his house in India. A young girl keeps asking about the odd and whimsical pieces, and the crisp HD footage leaves room for a surrealist dreaminess, something that is missing in the other venues.

Until a few days before the opening, the list of artists was withheld. Perhaps the gesture was intended to undermine the institutional PR machine — except, of course, the show relies on the institution as a carrier. In the 1990s, the Berlin Biennale served as the prototype of a new kind of exhibition, site-specific and critical, just when the former East-German capital awoke from its post-socialist slumber and was about to claim a place as one of Europe’s cultural centers. Innovation and experimentation put a political and sometimes utopian impetus at the heart of curatorial efforts; some would say curators turned critical theory into a decontextualized asset for a neoliberal art world. Nevertheless, criticality has been wired into the international biennial circuit, and together with cheap real estate, public funding, institutional critique, and relational aesthetics, it fueled a Cambrian explosion of biennials, triennials, and quinquennials in Europe.

The ripples of that explosion are still felt at the Berlin Biennale, and the exhibition sometimes asks the right questions, like: can art mediation be repaired? The answer remains oblique. Not class, says Attia in his curatorial missive, but disappearance of knowledge is responsible for proletarianization. In this biennial, however, between drifting from videos to flowcharts and reading wall texts, the curation risks flattening knowledge production into a continuous vibe, while the criticality circuit is overheating.