These days, the most compelling gallery exhibitions in Paris — and believe me, this isn’t always the case — are all about modern and postmodern art. I could mention the museum-quality show of Picabia’s late paintings at Hauser & Wirth, On Kawara’s early works at David Zwirner, and the Sylvie Fleury retrospective at Thaddeus Ropac. Gerard & Kelly’s exhibition “Bardo,” at Marian Goodman, also stands out, even though the references in their work, which uses the resources and approaches of the most contemporary if not conceptual art, are of a more general, formal nature. For anybody who saw their exhibition, it was a particularly exhilarating moment to attend, a few days after its opening at Marian Goodman’s, the public reading of On Kawara’s One Million Years (1999) at Zwirner, to which Gerard & Kelly participated, in the room where were exhibited the four monumental early works. As the time passed, the counting process was gradually incorporated into their bodies, second by second, minute by minute, giving a sense of the indirect yet intense connection between their work and On Kawara’s protocols, illuminating the understanding of one through the other.The work of Gerard & Kelly (Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly) revolves around a postmodernist, quasi-protocol-based choreographic lexicon, which is embodied in visual, filmic, and performative devices. It is based on in-depth archival research about the architecture of emblematic modernist buildings, which in turn become the sites of their experimentation and reflection, incarnated into moving bodies.

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus – “habit-made bodies” as socially constituted – resonates with Gerard & Kelly’s approach, which could therefore be seen as “archive-made bodies” that physically enact the history of the buildings they investigate. Their practice constructs a critical language that is both plastic and neo-choreographic, drawing from queer institutional critique and, more broadly, about the reflection it provides about minority conditions in modern and contemporary societies.

“Bardo” is structured around three bodies of works, with the video E for Eileen (2024) as its pivot piece. Shot at the modernist villa E-1027 overlooking the sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin — designed by Eileen Gray between 1926 and 1929 — the film expands Gerard & Kelly’s lexicon through a fictional device that transcribes and transposes the story of the mythical villa and its protagonists on a narrative and cinematographic level rather than a choreographic one. The video delves into the final days of Eileen Gray before her irrevocable departure from the villa she built for architect and critic Jean Badovici, her lover. The villa’s name, E-1027, encodes their initials: E for Eileen, 10 for J, 2 for B, 7 for G. The film is shot as close as possible to the villa’s architecture, the incandescent originality of its furniture — designed by Gray — the way its inhabitants engage with the space, and the movement of bodies through it. The archival research on which E for Eileen is based, its incarnation in bodies, the film’s intense physicality, the frontal way it is shot, the role assigned to the viewer, are close to Gerard & Kelly’s recurring protocols.

Facing the film projected onto the gallery’s vast basement wall, a convex cork architectural installation — one of Gray’s favorite materials — is placed on the floor. This structure inversely mirrors the partially hollowed-out shape of the villa’s red-and-black solarium, forming a shape into which it could seamlessly fit. By sitting on this complex, dais-like form, visitors become a homothetic element of the film, indirectly participating in Gray’s inner collapse. The solarium, perhaps the climacteric site of this breakdown, serves as a symbolic space, just as it does for the characters in E for Eileen.

The video probes the mysterious, opaque figure of Gray, raising questions that extend beyond her role as a pivotal figure in design and architecture. Exploring the enigma of her departure from the villa — never to return after leaving it to Badovici — E for Eileen raises the metaphysical and existential, though also socially constituted, question of the foundations of an individual person’s relationship to others, and to themselves. It examines the source of humiliation, which appears as the palpable outcome of a process of internalization of an embodied “self-hatred,” and whose victims, as we know, are several generations of the exploited, the inferiorized, the racialized and, more generally, those who deviate, whether voluntarily or not, from the dominant social norms.

Gray herself was such figure: a woman striving to break free from an inferiorized status in the 1920s and, more radically, to live as a free, openly bisexual woman. The video imbues the enigma of her disappearance from the villa with a strange depth that is at once historical, sociological, narrative, and universal, while simultaneously retracing a key moment in the history of architecture and engaging in a formal, aesthetic exploration.

On the wall, Solarium ensoleillé (2025) revisits the motif and color scheme of the solarium at the Villa in a stylized model under glass, made from painted mat board. This work evokes Kurt Schwitters’s Normallbuhue Merz (c. 1925) and is topped with Gray’s Pailla Wall Lamp (1927), which illuminates when the projection is in progress.

A series of light-box works display reworked photographs from Gray’s personal archives. Among them, Souvenir (after a Photograph by Eileen Gray) (2025) features two transparent images, tinted in gouache. One likely depicts the leather Transat armchair designed for E-1027, while the other possibly shows the façade of the villa, highlighting its blue blinds.

The title of the exhibition, “Bardo,” a term from Tibetan Buddhism that refers to “a transitional state between death and rebirth, during which consciousness undergoes profound changes,” embodies the concept of transition or passage. It suggests a state of renewal, which mirrors the evolution of Gerard & Kelly’s work at the time of this exhibition. In this context, the artists take a step away from their earlier approach, partially departing from both the choreography and the usual formal simplicity of their two-dimensional works.

The three-dimensional Glory Hole (2025) draws inspiration from Francesco Pesellino’s painting The Stigmatization of St. Francis (1442–5), housed in the Louvre. Crafted from polyester and gray resin and placed on the floor, the work evokes the queer figure of the 1980s clubber –– an emblem of a population decimated or even sacrificed by AIDS. It symbolically replaces the saint’s head with a disco ball, pierced by a chain that both suspends it and pierces his hand, emitting swirling points of light that illuminate the crypt-like room as if it were a nightclub of the era. The piece exudes a melancholy that also permeates E for Eileen, recalling the nightclub room adorned with disco balls featured at the Centre Pompidou during the artists’ choreographed performance Gay Guerrilla (2023).

Gerard & Kelly’s work leaves nothing to chance, and maintains a process of cross-referencing and recurrence from one work to the next. A quick search reveals that in the early years, disco balls were used to illuminate places such as “a 1912 solarium for tuberculosis patients at the Milwaukee Hospital for the Insane” (David Garber, “Meet Me Under the Disco Ball: A History of Nightlife’s Most Enduring Symbol,” Vice, June 4, 2015), evoking once again the solarium and the existential questions raised by E for Eileen. The posture of the three-dimensional character echoes that of Badovici in the film, who, returning drunk from a party, collapses to the floor to undress — a scene that also recalls their video Modern Living (2019), which stylizes Le Corbusier’s penchant for undressing himself. Like Glory Hole, E for Eileen unfolds in a festive atmosphere that perhaps leads to downfall or sacrifice.

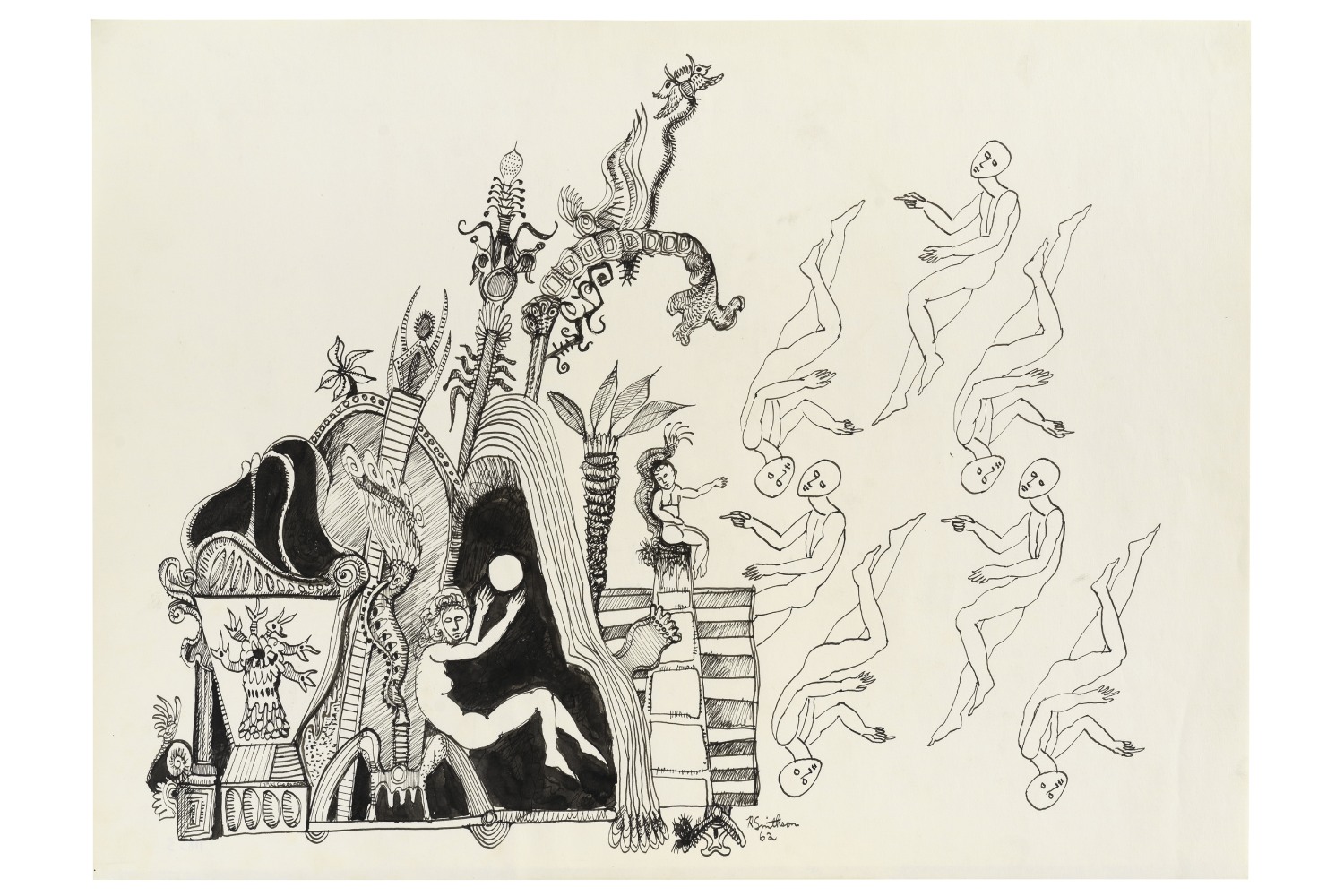

A final series of two-dimensional works, indicated by another Gray’s Pailla Wall Lamp (1927), which illuminates when the projection is in progress, some enhanced with neon, once again reference Gerard & Kelly’s musical and choreographic performance Gay Guerrilla (2023), inspired by Julius Eastman, a Black queer American composer who died young. The “Glyphs” series (2023–2024) — silkscreen and gold leaf monotypes on metallic paper, interwoven with scriptural elements — functions as a choreographic notation system for this work, carrying a subtle Warholian influence reminiscent of his early black-and-white period. Pompidou Pulse (2025), a collection of silkscreened and acrylic figures on canvas accented with red neon, also evokes Gay Guerrilla while adopting a more pop-inspired visual language. The shift introduces a new dimension in Gerard & Kelly’s practice, one that moves further from the physicality of dance and minimalism, and is of an extreme coherence.