Bruno Zhu is a stylist par excellence, that is, one who knows that surfaces cut deep with conspiracy. Never simply superficial nor left unscathed, surface is manifestly outed in Zhu’s “License to Live,” despite applications that imply all looks exactly as it should, as neat as a bow. A background in fashion design informs Zhu’s engagement with the semiotics of presentation and the socioeconomics of cultural production, underpinning projects of punchy formalism and promiscuous intellect within equally idiosyncratic contexts. Sometimes his work rejects the assignation of art entirely.

“License to Live” is, in fact, all display and no filler, or at least no artworks per se. Zhu’s response to Chisenhale Gallery’s commission magnifies the terms of the commission as such. Specifically, as Zhu notes in the supporting literature, the “recoupment” clause stipulates that the institution recover the production costs of said financed commission. Counter-voicing this, Zhu authored a license agreement that specifies guidelines for the exhibition’s design. Introducing a model of commissioning as seriality, whose open circulation knowingly flirts with insatiable “newness,” the license provides Zhu and Chisenhale the possibility of equal remuneration. Such a maneuver makes a joyride of legitimacy and blows a lip-glossed kiss to institutional critique.

A license’s hegemonic textuality must assume compliance from the outset while posturing permission as a kind of mercy. That Zhu plays this dominance like a house of cards allows for sensory gratification, even entertainment, its performative “logic” amplified to sassy totality in his droll command of space. Here, an emphasis on ornament, color, and orientation exacerbates rationality through extravagant, categorical fictioning. Limitations are literalized at the exhibition’s two green doors, entrances that motion a trivial choice which tickles agency. Taking the left (naturally) opens onto one of four interconnected rooms that comprise “License to Live”. Signaling the cardinal points, this room’s walls and the planes of the exhibition’s six doors are each painted shades clarified by the license as: Vermilion (Cinnabar), Scheele’s Green, Naples Yellow, and Cobalt Blue. Artworks in this room must conform to its palette and be displayed upon the surface correspondingly. Such tones are chosen for their indecent histories of extractive manufacture and whose chemical compounds cite the artificiality and toxicity that hued nineteenth-century tastes. Saturating the floor is Perkin’s Mauve – a commercialized tone recognized as one of the first synthetic dyes, created after failed attempts to synthesize antimalarial properties. Orienting the viewer in a coded compass of deceptive pigments, Zhu takes the slippery opticality of surface on a race to the material bottom as visitors, too, must navigate its downward spiral.

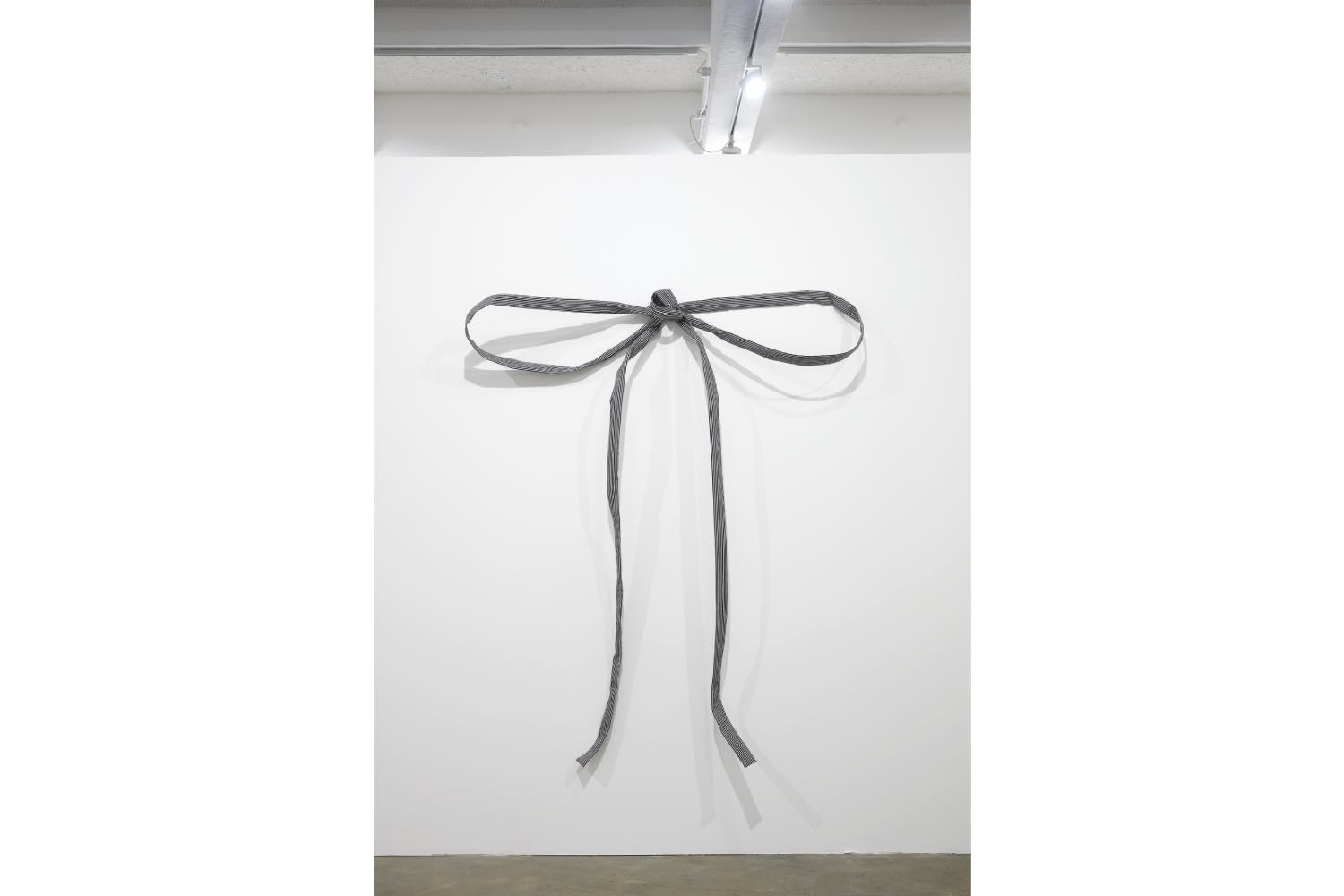

Moving clockwise, the adjacent room houses four conjoined mirrored cabinets, each aperture shaped by the outline of French-suited playing cards: club, diamond, heart, and spade. Per Zhu’s license, objects in this room can only be presented within the confines of the display. These vitrines lack glass defenses and frame nothing, yet their diamondized interiors conflate both subject and object in fetishistic adherence to declarative shininess. Zhu’s cabinets convey his attraction to the elasticity of generic symbols when hollowed of history, in this case as regional markers of social status. That a nuanced understanding of this history is contingent on his generous mediation in the exhibition’s handout compounds the exuberant opacity on severely glitzed display. Flip-flopping from the rarefied to the rudimentary, an elephantine pinstripe bow occupies one wall of the following room. It heralds the ruling that objects can only exist within this space if they are tied with a bow, thereby domesticating any would-be object and codifying the context itself within the ostensible mobility of a gift economy. Here, Zhu’s license effectively italicizes a more complicated discourse of observation and objecthood, circulation, and possession.

The final room is clad in mass-market imitations of stately interior designs — parquet flooring, damask wallpaper, and ceiling decorations — in a room tilted to its side. Climaxing disorientation, artworks must obey the new spatial and gravitational laws of this arrangement, where the floor and ceiling now define opposing walls. Placing imperialist heritage in glitter-penned quotes, these multicentury textures are read against their plasticky grain, plastered like a surplus of Pinterest virtuality. Gone are the days of their origins, yet this lack is embraced by Zhu, its hyperlinked pastiche allowed to free-associate sincerely rather than satirically. Stretched of prestige, the room demonstrates the expressive potential of aphoristic self-fashioning to an absurd extent, dramatizing the difference between styling and stylization. Specifically, how the latter’s efficacy depends on normalized delusions in the excitation and satisfaction of libidinal economies. The room’s maximal aberration skewers the reverence for concretive stylization, exposing its executions as always context specific and always at a cost. How do I know? Because it’s willfully ugly. Because it’s peak gay. Because it screams wannabe. Just as this license makes a commodified spectacle of itself, so too does each design perform its own theatricalization.

Zhu’s study of display is surely one that swoons under the legacy of Derrida’s “parergon” — that which constitutes the very border between things yet is nothing in itself. In a word: dressing. “License to Live” is a study of definition, of how things are defined and by whom. What is most palpable in this ecstatic hermeticism is everything that is lost in its process. The emptiness: if the rationale of parergon is self-elimination, where does that leave us here? “License to Live” is giving me life enough to recognize that what this show really wants is for you to know you’re free to leave.