There is an inevitable temptation in the explication of any artwork to resort to the anecdotal — a persistent urge to narrativize the creation of an artist’s work in a personal or moral story. In this justification the anecdotal is dragged into a defense against a possible negation and becomes part of the “why” of the work. But it is the “how,” not the “why,” as Denise Ferreira da Silva writes, that is important in allowing the artist to describe, or be described as, more than a “condition of the world” – that empowers them to express “the condition of their being in the world.”1 You could say the how fills the frame in Akosua Viktoria Adu-Sanyah’s exhibition “Corner Dry Lungs” at the Museum für Moderne Kunst – ZOLLAMT, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

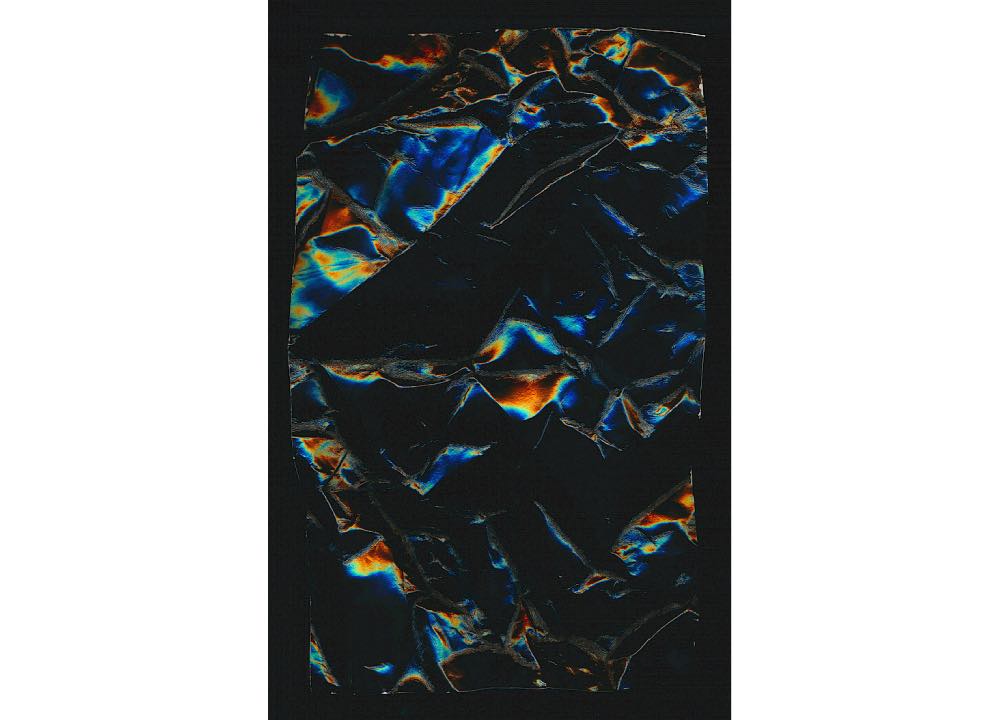

It is complicated to say what the frame of the exhibition is. Is it the photographic paper that receives the image — the ambient light of the space — or is it the space itself, the place where the work of exposing, developing, crumpling, and mounting the paper happens? The works in “Corner Dry Lungs” (there are fifty-six works, titled “lungs” plus a number) are mostly monolithic squares made of two long photographs stapled to some very efficiently elegant frame-like supports. The works were all made in situ, so the space is and suggests itself to be a workplace. The strange chemical smells, low lighting, stains, and standing water create the atmosphere of a tannery or another processing plant. Some of the works, being re-wetted and stretched more tightly than others, look like leather – the edges bitten and torn from stapling — but the majority of the works are shiny crumpled surfaces, having more texturally in common with glass or metal than skin. There are neatly scattered ad hoc tools: wooden boxes for dousing the rolls, palettes with buckets half full of solution.

When I saw the show in early December, the pieces were arranged more or less pragmatically, like in a studio. The supports on which the paper is mounted resemble work tables or very thin slabs leaned against the walls. They were designed to be easily carried by two people, and most of the show is installed at the discretion of the art handlers. During the developing process the photosensitive paper is opened in the space with the lights on and soaked in developer, exposing it directly to the room without any negative or filtering device. This saturates the image through a range of colors to a point of blackness. The photographs are then rinsed without any chemical stop being applied, leaving the process unfinished. The artist worked through the opening and has returned for a number of “activations,” an annoying designation that I understand the need of – how can an artist be present not as a performance? The rearranging and re-activations underline the ongoingness.

I had originally confused the photographs, in pictures on Instagram, for some type of covering; they looked like large glossy trash bags on enormous panels. Texting with Lukas Flygare, who curated the show with Susanne Pfeffer, I imagined there were delicate prints underneath. Encryption in digital communication borrows the terminology of burial – the crypt – to explain how something is hidden, covered over. I was told — and I believe — the show is about mourning. Upon visiting, the first art-historical association I had was of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, a place with deep anecdotal meaning for me. Both in Adu-Sanyah’s installation and Rothko’s chapel there is a complicated quietude, a meditative atmosphere that feels tensely fraught. The work in Frankfurt, though, is somehow more intellectual, more fitting to how we process feeling now, and also fitting to our contemporary art — more analytic. Rothko insists upon and in a way brutishly forces transcendence on us; Adu-Sanyah’s show feels more gently about immanence.

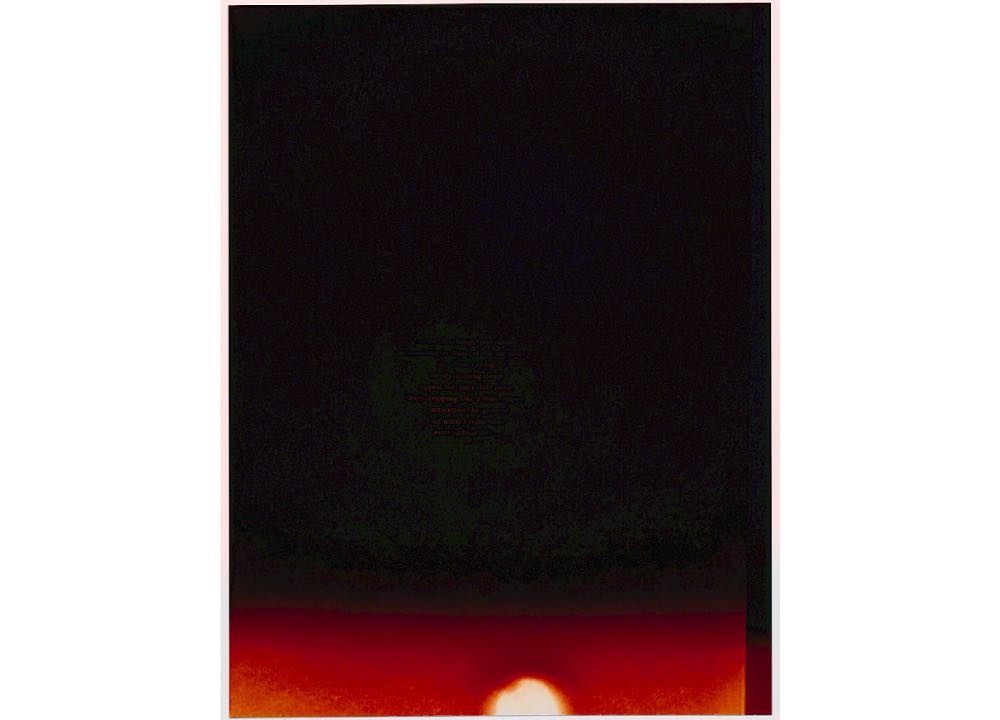

In the lower right-hand corner of the only triptych, Lung 25 (2024), there is the most Pictorialist (read: beautiful or painterly) landscape, a hazy sky full of clouds, the edges silvery with moonlight. Pictorialism was an aesthetic movement stuck dialectically — ChatGPT pointed out to me — between ambitions of immanence and transcendence, the moment when photography sought specifically to express itself as more than a technological medium. Comparatively, the photographs in “Corner Dry Lungs” are paradoxically sparse in the scope of their imaging, merely the overexposure of one space, and immense in the proposition of an existential experience, muddling sense and subject. When I first saw the Rothko Chapel I thought: heaven but no God in it. It was a haunting feeling of transcending into emptiness. Adu-Sanyah’s exhibition is a grounding where light is present with such saturation that it looks like darkness and describes abundance. This is how the works were when I saw them, “already and not yet”2 all that they would be.