Postponed for six months due to political turmoil last spring, the fifteenth edition of the Biennale of Contemporary African Art in Dakar, titled “The Wake: L’Éveil, Le Sillage, Xàll wi,” presents an ambitious project that urges societal change through art from the African continent and its diaspora. Partially inspired by Christina Sharpe’s book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), the title is intentionally open to multiple and equally valid interpretations. This openness aligns well with the Biennale’s overall curatorial concept, but – at times – would have benefitted from more precise guidance among the fifty-eight artists selected by Salimata Diop, Dak’Art’s artistic director, in close dialogue with curators Kara Blackmore, Marynet J, and Cindy Olohou. Nevertheless, many of the works showcased possess undeniable aesthetic value and meaningfully respond to the chosen theme, the wake.

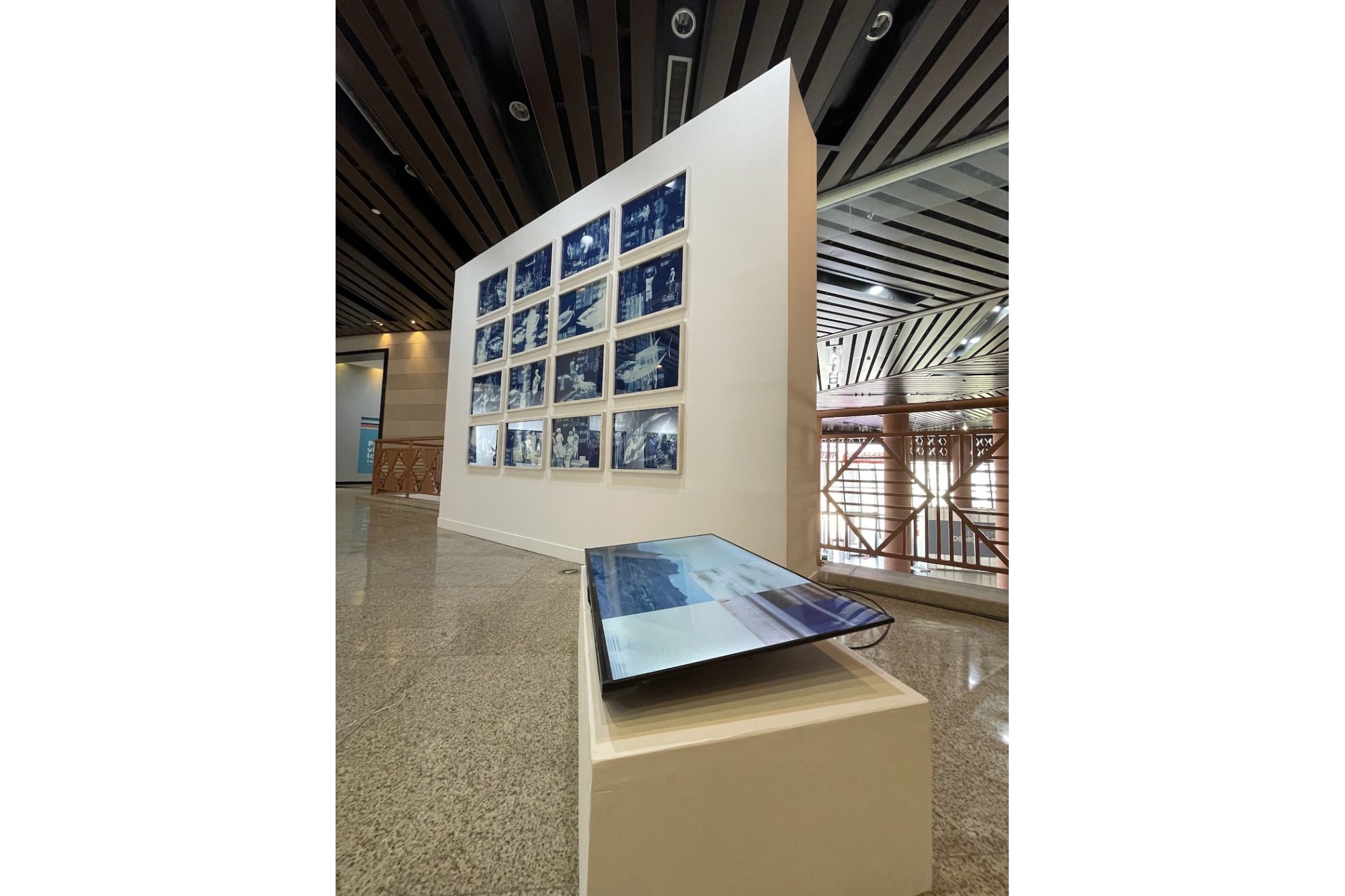

“The Wake: L’Éveil, Le Sillage, Xàll wi” opened in early November across three main venues in Plateau, Dakar’s historic neighborhood and contemporary economic hub: the Ancien Palais de Justice (the Old Courthouse), the Musée des Civilisations Noires, and the Galerie Nationale d’Art (National Art Gallery). This year’s reactivation of the Old Courthouse is a notable initiative. Diop aptly described her curatorial approach as a confrontation with “the Monster Palace,” a process of “metamorphosis.” Curatorial efforts to address the building’s colonial legacy — a burdensome yet significant historical marker — achieved mixed results.

This is true especially for the Haitian American artist Gina Athena Ulysse’s installation For Those Among Us Who Inherited Sacrifice, Rasanblaj! (2024), an assemblage of natural and ceremonial objects installed on the building’s façade. Despite the quality of the work, the curatorial strategy recalls similar gestures seen in other biennials — such as Oscar Murillo’s dirty canvases in front of the main pavilion during the Okwui Enwezor’s Venice Biennale —and risk coming across as an aesthetic escamotage rather than a vigorous effort to take a grievous piece of history into its hands.

Conversely, Nairobi-born artist Wangechi Mutu’s intervention in the former Supreme Court chamber, the symbolic “heart of the beast,” is more impactful. A Palace in Pieces (2024), presented alongside two early 2000s videos, is a site-specific intervention that drew inspiration from the trials and uprisings that had taken place in that room. Her Mountain Mama (2024) — rooted in an Afrofuturist vision of an underwater world — simultaneously embodies an uncanny familiarity and a fairy-tale sensibility as it celebrates feminine figures both ancestral and contemporary — a recurring motif in the exhibition.

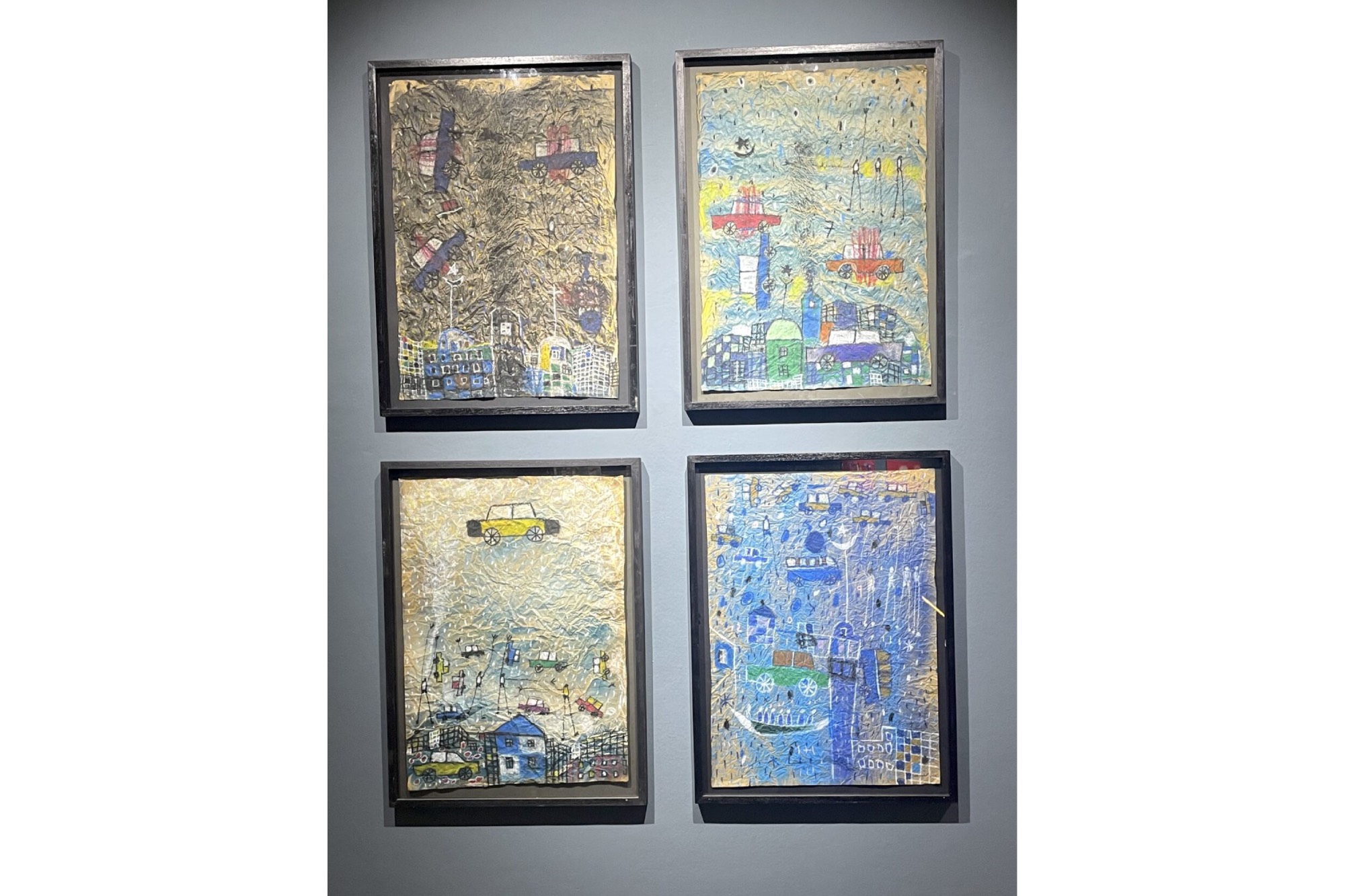

Collaboration with museographer and scenographer Clémence Farrell enhanced the Biennale’s thematic vision of “a journey through an Atlantis that artists have secretly repopulated.” The upper floor of the Old Courthouse, previously clerks’ offices, now features bluish lighting and projections that transform the space. However, assigning most rooms to a single artist detracted from the original curatorial intention of creating a unified, synesthetic experience. The ocean is mainly a remote presence mirrored in the work of a few artists, such as Arébénor Basséne’s Méditez-rat-n’est-rien (2024), a series of eighty-eight abstract paintings in acrylic and natural pigment on paper, which elegantly seal off one of the Old Courthouse’s corridors.

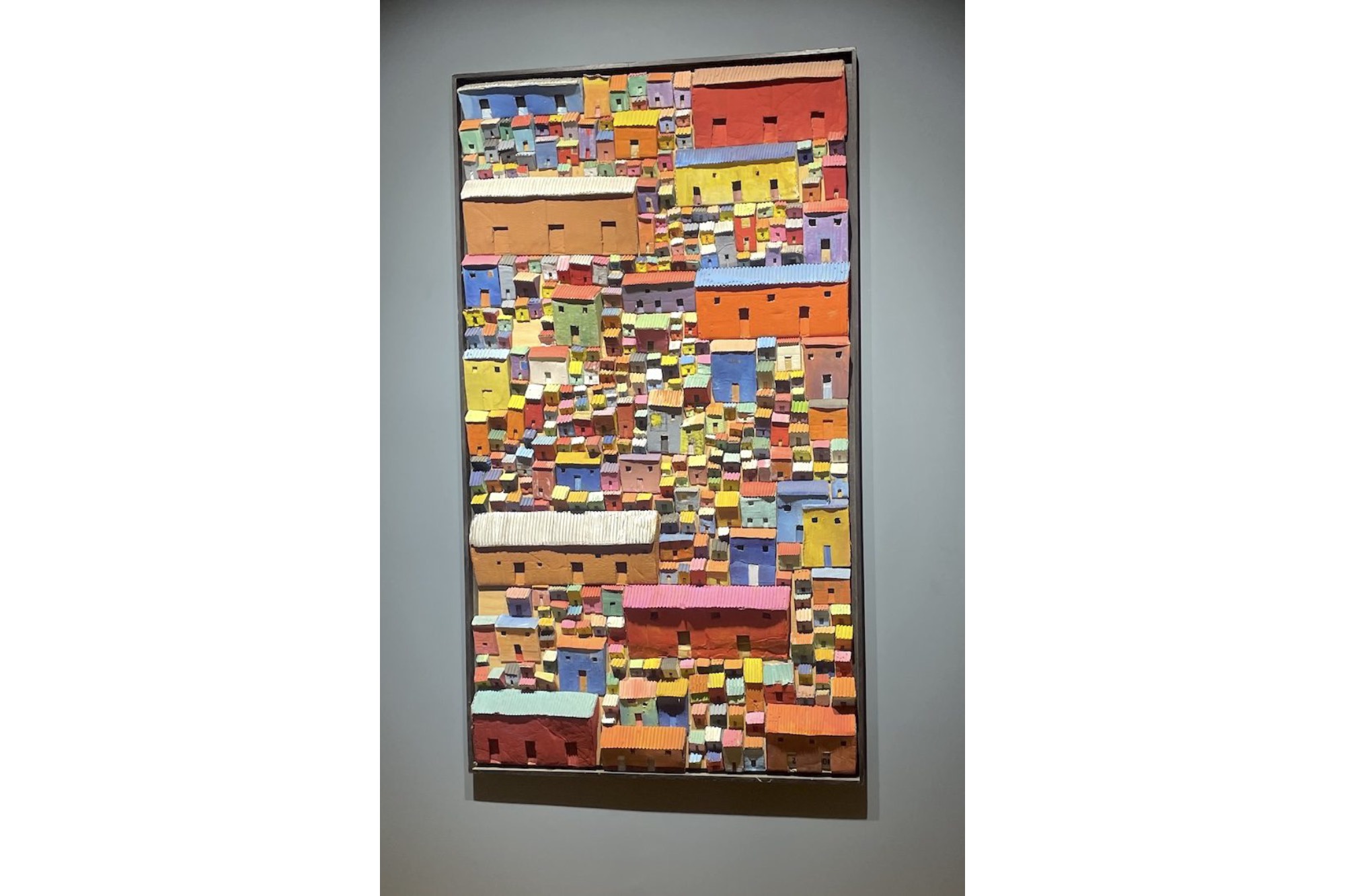

Will anyone exit the confrontation between the “monster” and the fifteenth edition of Dakar Biennale unscathed? The exhibition is articulated in a succession of four chapters: “Swimming in the Wake,” “Dive into the Forest,” “Float in the Cloud,” and “Burn.” Most of the artworks can be appreciated as singular elements, isolated from the rest. Some of the exhibition rooms were dedicated to figurative paintings such as Dior Thiam’s portraits on multilayered diptych, Particles I and Particles II (2023), and Elladj Lincy Deloumeaux’s set of ten pastel and oil paintings, Reflections of Solitude (2024), documenting the male black body in intimate and dream-like poses.

Familiarity with the artists, many of whom have recently participated in major international events like the national participations at the 60th Venice Biennale or Manifesta 15 in Barcelona, enriches the experience. Paris-born artist Marie-Claire Messouma Manlanbien’s embroidered textile pieces, including Mamiwata Water (2023) and her “Maps” series (2018–20), interrogate the relationship between humans and the environment. Odur Ronald’s The Fabric of Identity (2024) requires visitors to stop and decode what is written in his aluminum-made copies of passports from fictional countries hanging from the ceiling.

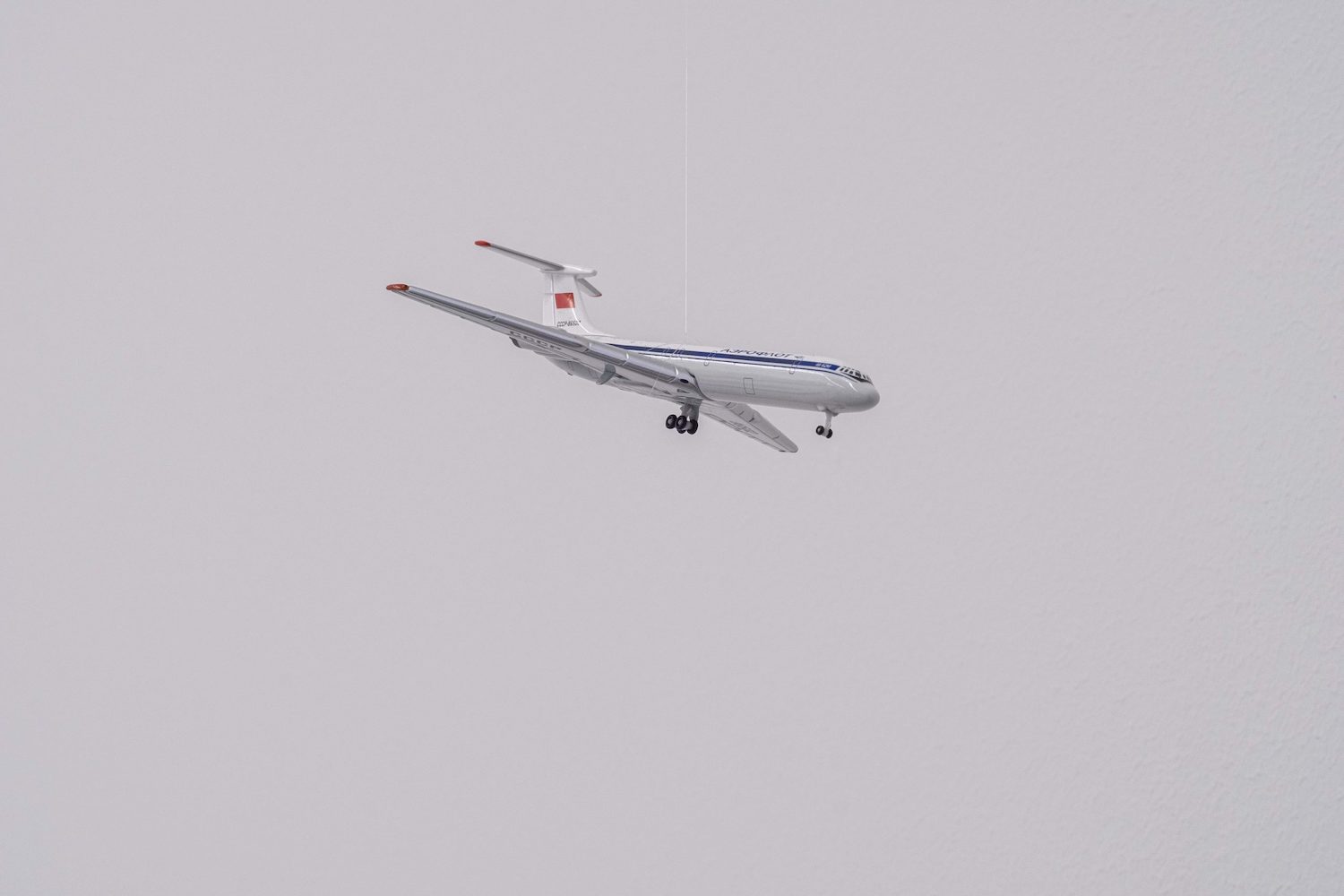

Pleasant surprises include Shivay La Multiple’s site-specific installation In search of the woody fruit (2024) and artist duo Lo-Def Film Factory and Russel Hlongwane’s video installation Dzata: The Institute of Technological Consciousness (2023), both of which look toward parallel, alternatives futures in a playful, ironic manner. Dominican artist Lizette Nin’s multimedia installation We Were Clay in a Red River (2023), which unorthodoxically portrays Black women’s braided hair from above, resonates with Sonia Barrett’s collective project Map-elective (2024) which uses the practice of braiding and deadlocking to sculpt pieces of paper maps into an immersive installation in the Biennale’s courtyard.

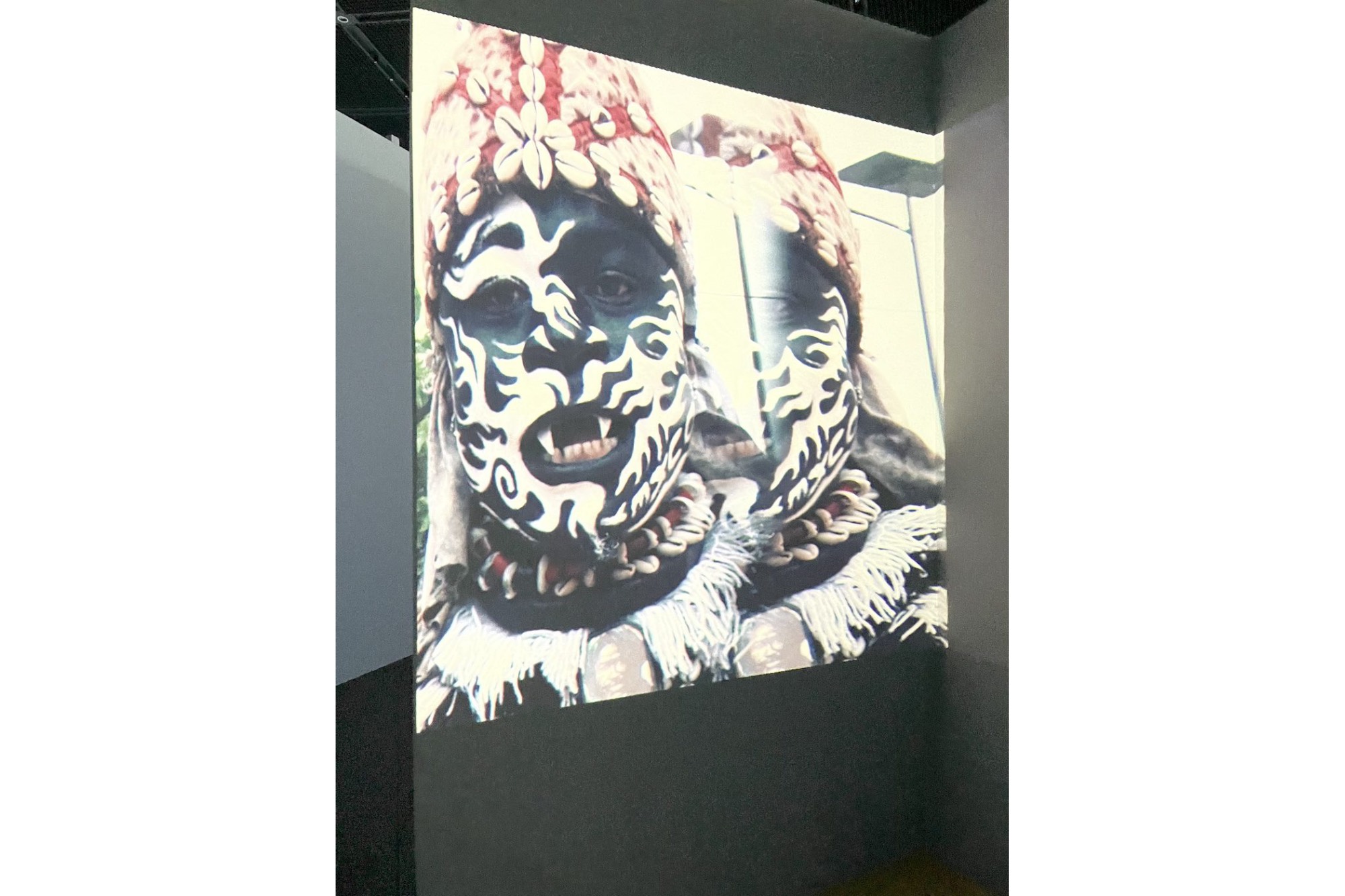

Filmic works also made a strong impression, such as Namibian artist Tuli Mekondjo’s video-performance work Saara Omulaule: Black Saara (2023), which revives Indigenous spirituality and rituals, and Astrid Gonzalez’s short video Hablar a Plantas (2021–22), which exalts Afro-Colombian, nature-based medicine. With its golden chiaroscuro and beautiful but melancholic imagery, Tunisian filmmaker Younes Ben Slimane’s twenty-minute video We Knew How Beautiful They Were, These Islands (2022) successfully illuminates the dark bowels of the monster, the Old Courthouse.

It remains to be seen whether inviting other curators to present concurrent exhibitions effectively enhanced the resources already in place. Although beautifully crafted, the ten-artist group show “We Will Stop When the Earth Roars,” curated by Blackmore, Marynet J, and Olohou, overlaps in many instances with the main exhibition’s themes. On the other hand, the “haptic library,” a room dedicated to rest and study, curated by Archive Ensemble, is an indispensable addition. In the absence of other artworks with more participatory and collective dimensions in the main exhibition, that space contributes to maintaining the Biennale’s temporarily formed but close-knit community.

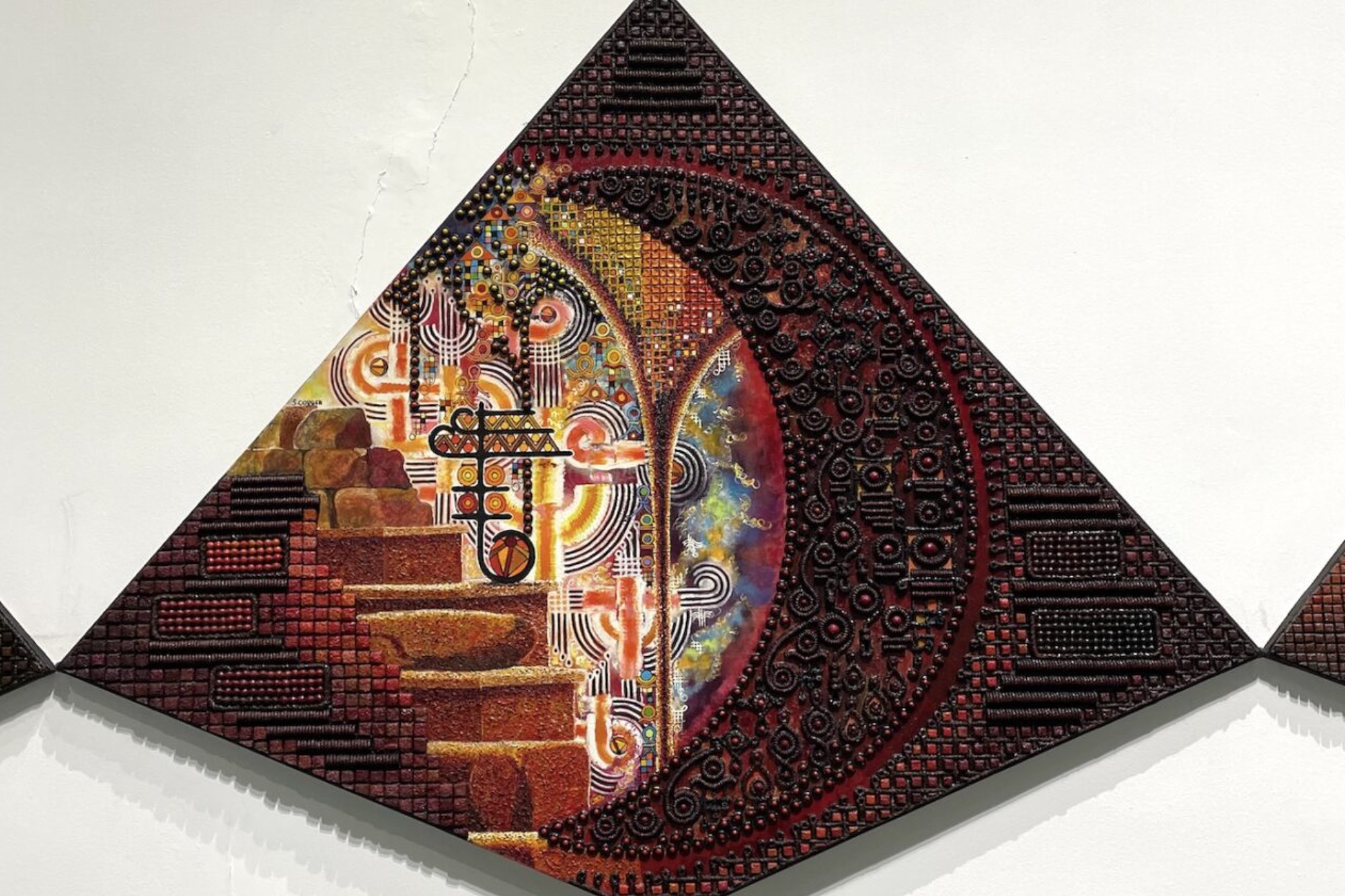

After a brief pause in the library’s improvised living room, my last bit of energy was directed to a pair of exhibitions paying homage to master Senegalese artists Anta Germaine Gaye and the late Mouhamadou N’doye (N’doye Douts), which were distributed between the Old Courthouse and the National Art Gallery, with Salimata Camara and Sylvain Sankalé as the respective curators. Additionally, a quick tour of the Musée des Civilisations Noires felt obligatory, not only because of the three national participants (the US Pavilion, the Senegalese Pavilion, and the Cape Verdean Pavilion) but also to gain a deeper acquaintance with African heritage.

Overall, the vibrancy of the artistic proposals and the original exhibition concept make “The Wake: L’Éveil, Le Sillage, Xàll wi” an exhibition worth visiting. It would be limiting to read the 2024 Dakar Biennale, one of the longest-running state-funded biennials in West Africa, as merely a showcase of the best art from the continent.

“The Wake” is a powerful show that confronts the idiosyncrasies of our times with agility. It engages with Africa as a space defined by people’s sense of belonging rather than territorial confines. Finally, it boldly addresses the scars of global imperialism that still haunt the present, the persistence of which is met with resistance from the artists. This is what the term “wake” came to mean to me after I visited this year’s edition of the Dakar Biennale.