During Art Basel Paris this year, the big deal in the city was the return of the fair to the Nave of the Grand Palais, after two editions in the ephemeral structure designed by Jean-Michel Wilmotte. Even for those familiar, like me, with Paris and this iconic building — with its emblematic glass roof, originally built for the 1900 Universal Exhibition and renovated several times — strolling through the fully restored Grand Palais, with all its original architectural features reinstated, was a pretty exciting experience. It seemed like everyone was thrilled to be there. Under the direction of Clément Delépine, this third edition of Art Basel Paris (formerly Paris+ by Art Basel) was more than generously decked out with important, even museum-quality works, mostly contemporary but also modern. Surprisingly, the stands were generally restrained, even minimally curated, including the emerging galleries on the upper floor – a sign of a return to sobriety.

This new trend toward sobriety also set the tone for the extensive program of Parisian exhibitions during Art Basel.

At the Petit Palais, “Vanitas,” a solo show by Jesse Darling, winner of the 2023 Turner Prize, combined under the stucco ceilings the reprise of the austere metal crowd barrier distortions that were exhibited for the Turner show, stemming from a reflection on power and its ephemeral nature, and the reactivation of the large-scale installation Still Life (2017–ongoing). Scattered throughout the entire exhibition space, twenty glass structures on plinths, echoing the shapes of display cases from the history of exhibitions at Petit Palais, enclosed bouquets of flowers in vases, becoming the site both of their display and of their accelerated decomposition.

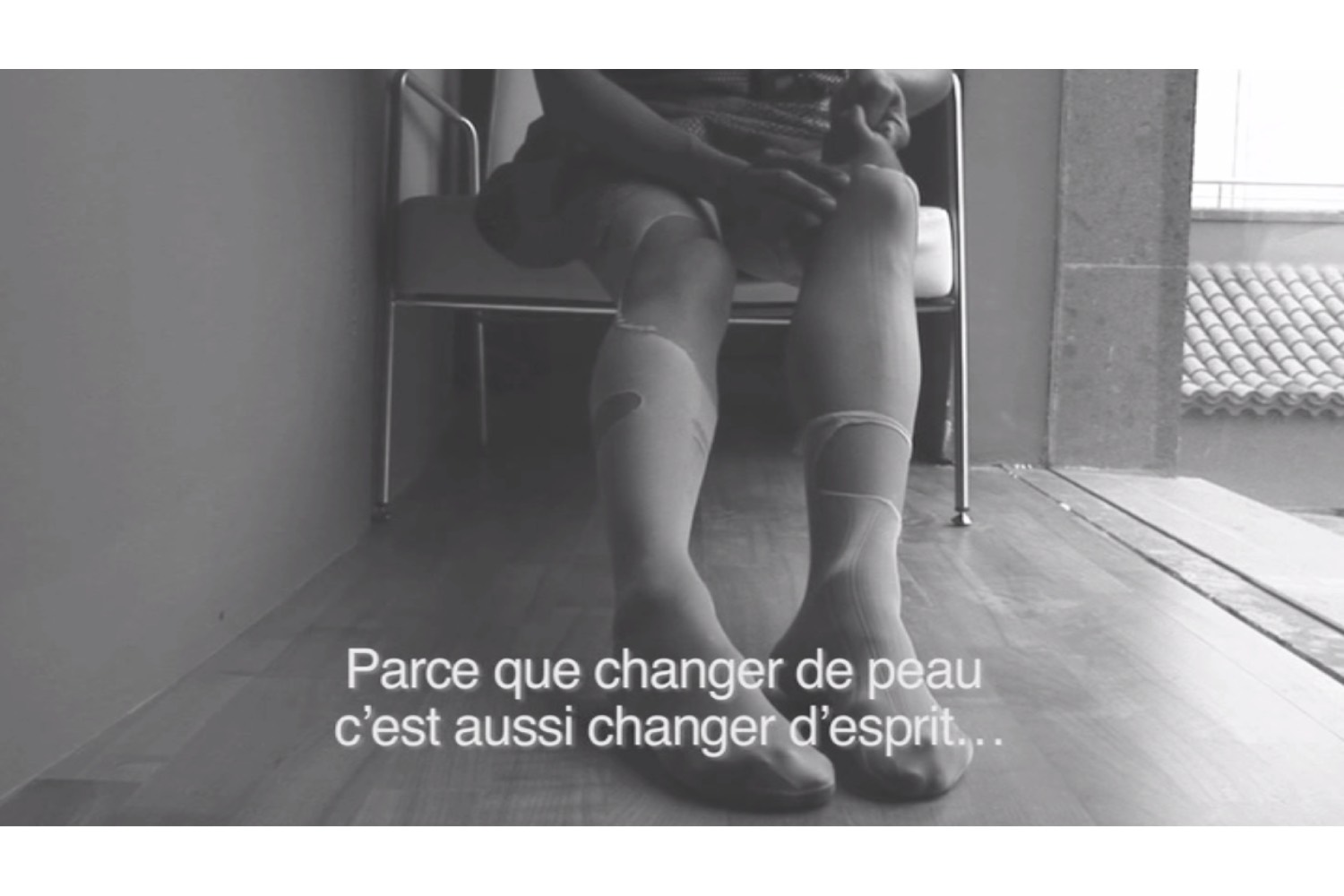

Further west, at Palais d’Iena — a monumental modernist concrete utopia built in the 1930s — “Tales and Tellers” offered a mysterious hybridization of art and fashion. Conceived by Goshka Macuga and Elvira Dyangani Ose (curator and director of Barcelona’s MACBA) for Miu Miu, the show featured a selection of video works and filmic devices by female artists including Miranda July, Alice Rohrwacher, Meriem Bennani, Shuang Li, Cécile B. Evans, and Agnès Varda, all commissioned by the brand since 2011. Displayed within sculptural installations, the videos were partially reenacted by performers dressed in Miu Miu, who then paraded among the audience, blurring the boundaries between spectators, performers and models, art and fashion.

Inside the ornate baroque chapel of the Petits-Augustins at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Jean-Charles de Quillacq’s installation A Real Boy (2024) sprawled across the space. Made from poverist materials like polystyrene, denim, bread, cigarette butts, and car coolant, the work featured casts of male body parts, reprising a major exhibition by the artist at Marcelle Alix gallery in 2023.

These relatively sober public exhibitions during Art Basel Paris focused on hyper-contemporary art and were complemented by a program of conversations at Petit Palais, along with a series of installations scattered around the city’s emblematic sites – such as Carsten Höller’s three-meter-high Giant Triple Mushroom (2024) at Place Vendôme and a series of sculptural works in the Palais Royal Gardens. These offerings would have been enough to nourish any visitor, but there were also, as usual, a vast array of exhibitions to explore in Parisian institutions (many on view until January) and dozens of alternative fairs to discover.

From Paris Internationale, celebrating its tenth anniversary, to “The Salon” by NADA & The Community (the first edition of a formula initiated by The Community), to Asia Now, partially curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, and OFFSCREEN, which this year dedicated a vast room in the emblematic Grand Garage Haussmann to the work of Chantal Ackerman and featured an installation by Alfredo Jaar – the quality of these shows was exceptional, while others were blooming.

As an antidote to the concepts of art fairs and commodification, “Total,” a critical installation by Martine Syms curated by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel at Lafayette Anticipations, offers a profound philosophical and political reflection on these issues, as well as on the experience of Black and queer women in the United States. Spanning almost the entire building, the show echoes the structure of a department store, presenting both key works by Syms in a retrospective approach and multiples presented on stands as if they were “goodies” that visitors can purchase directly for modest prices, sparking a reflection on the value of art and its commercialization. e exhibition features photographic works like Studio Wall (2024), a life-size wallpaper- canvas reproduction of Syms’s studio desk in LA, augmented with post-its and stickers, and video installations such as Lesson XXV (2017), a performative work that plays on a small screen embedded in a T-shirt message (a rack of these garments is on sale nearby) in which, in a political gesture, Syms sprays her face with milk. All one hundred and eight works from the series “Lessons I-CLXXX” (2014–18) are also displayed in an installation.

This “total” exhibition can be read at another layer of philosophical reflection, as it is also conceived both as a film set and a surveillance device: visitors are filmed as they stroll through the space, mirroring their experience in public spaces. In a control room on the top floor, they can contemplate the live images they are a part of – images that will eventually become elements of a future work.

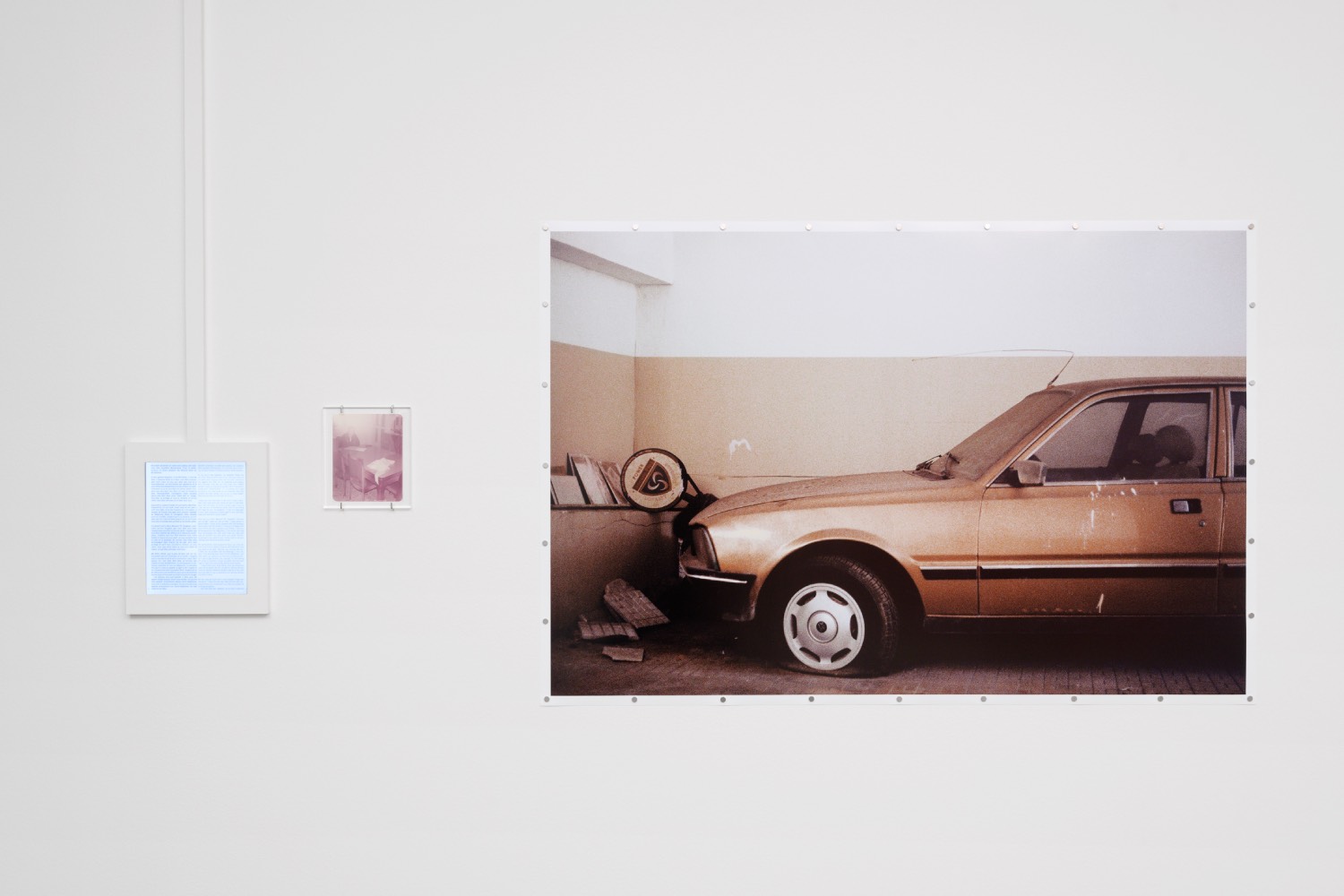

Also at Lafayette Anticipations, Mohamad Abdouni’s short exhibition “Soft Skills” explores queerness in the Middle East through an introspective journey into the archives of his Lebanese childhood. The installation includes a series of plants rising on pedestals or expanding on walls, saxifrage-like. They include in their rhizome photographic and three-dimensional works drawn from these archives, which fill-in their unspoken dimension with fictional elements developed by AI and new technologies, creating non-existent images in which queerness can be exhibited.

As Centre Pompidou prepares to close for five years of renovation, it presents a similarly sober program of contemporary art, alongside its extensive “Surréalisme” exhibition, organized in a spiral around the original manuscript of André Breton’s Manifesto (1924), as well as the museum’s always outstanding collection display.

Under the ideogrammatic title mù (the gaze), the exhibition “Chine, une nouvelle génération d’artistes” showcases works by twenty-one emerging Chinese artists, co-organized with the West Bund Museum. Alongside some pieces already well known in Europe, such as Lu Yang’s video DOKU The Self (2022) and Chen Fei’s The Road to Success (2023–24), the works, and their distribution within the space, suggest a radical newness.

A series of acrylics on canvas by Cui Jie, which evoke architectural elements and break down the image schematically, is mounted directly onto Diplomatic Species (2024) – a large wall covered in printed paper reprising pattern of a Chinese industrial silk from the 1960s, adorned with a rectangular excavation reminiscent of Dong’an Park. Yu Ji’s vertical sculptures incorporate diverse materials like soap, concrete, and stainless steel, while Colour Box (2023), by Wan Yang, sculpturally assembles several elements of small-format 3D-printed photosensitive resin grids, each cell being filled with colored oil paint.

The Marcel Duchamp Prize, which showcases the work of four shortlisted artists each year at the Pompidou, devotes its first room to an installation by Gaëlle Choisne, the 2024 winner, which condenses her different practices. On the floor is Ruches Creoles Garden in Normandie (2024), a cork path dyed black and inlaid with fine gold chains, upon which sits five sculptural elements, each containing a video shown on a small glazed ceramic screen. On the wall, Safe Space for a passing history–Ère du verseau 99999 (2024) is a series of large-scale paintings on wood panels that Choisne calls “scrap-paintings” (a nod to “scrapbooks”), as they are enhanced by printed photographic elements and collected or handmade objects, some in ceramic. The other nominated artists — Abdelkader Benchamma, Detanico/Lain, and Noémie Goudal — also present large-scale installations.

But perhaps the most exciting aspect of the Pompidou’s contemporary program is its comprehensive Apichatpong Weerasethakul retrospective, “Des lumières et des ombres,” conceived as an extension of “Surrealisme,” of which the artist claims to be a contemporary heir. Curated by Marcella Lista, it offers a thrilling response to the recurring question of how to show video works in an exhibition setting, playing on the architecture of the Atelier Brancusi, which has been exceptionally emptied and plunged entirely into darkness. Inside the studio’s central architectural structure, Solarium (2023) is projected onto a double-sided glass screen, with the recurring figure of an eye — a nod to Surrealist iconography — invading the entire space. Ten silent shorts from the “Video Diaries” series (2002–22) are projected onto the painted-in-black bottom wall of the studio, with very small screens, while Seeing Circles (2022) is shown on two circular screens, arranged into a column evoking a sculpture reminiscence of Brancusi’s. The exhibition is accompanied by an extensive retrospective and talks in the Centre Pompidou cinemas.

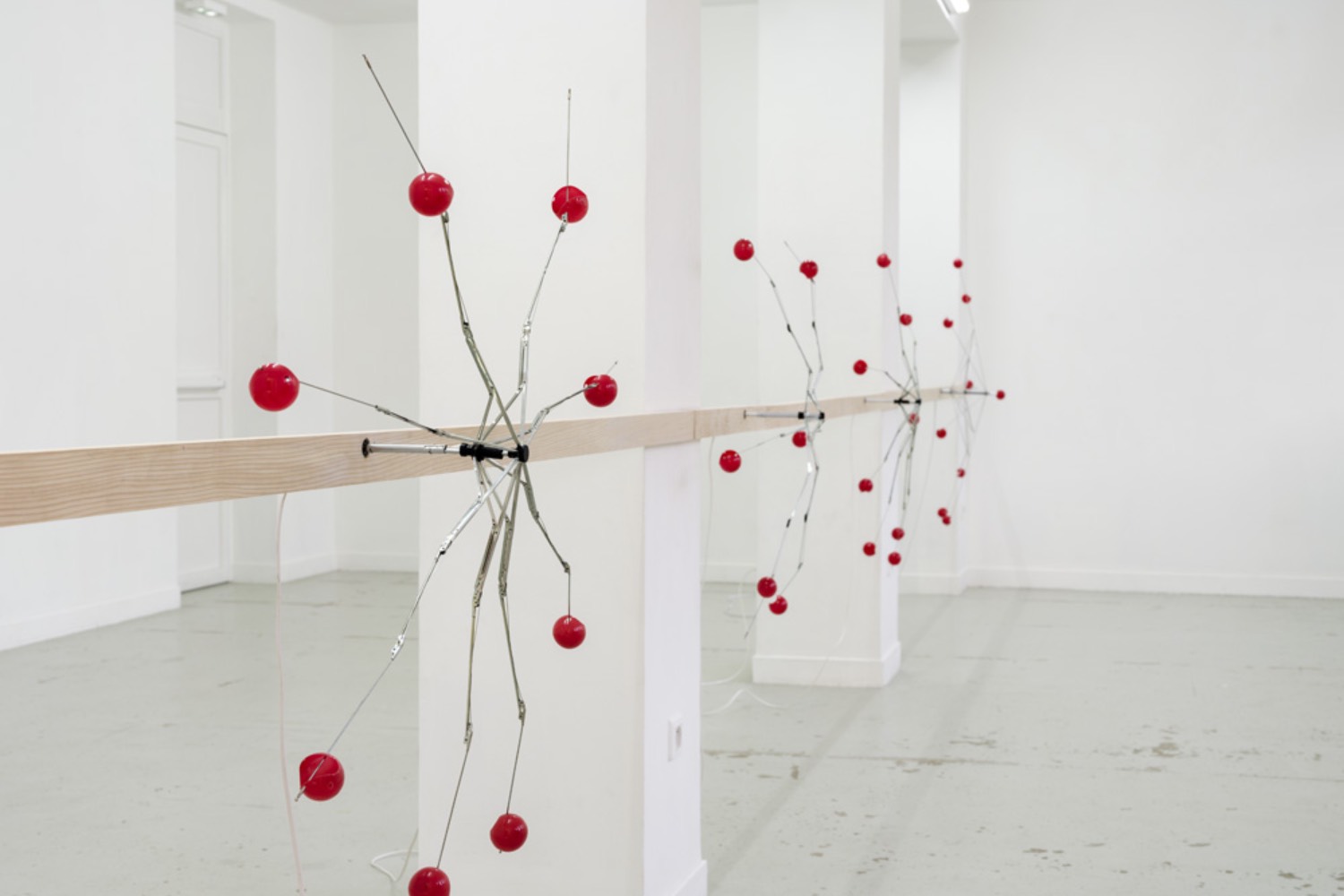

Also at the Pompidou, “Art contemporain en Lituanie de 1960 à nos jours,” curated by Alicia Knock, offers a brief, hard-hitting panorama of the contemporary Lithuanian art scene. Among its highlights is The Return of Sweetness (2018), a major work by Pakui Hardware, who represented Lithuania at the sixtieth Venice Biennale. Composed of glass, textile, latex, and steel wire, the work is suspended at both ends. The show includes notable pictorial pieces, and it resonates with the retrospective devoted to the emblematic Lithuanian Op artist Kazys Varnelis (1917–2010), whose Convex plus Concave (1971), a canvas with regular patterns evoking scales, has been a source of inspiration for many artists.

At the Bourse de Commerce, a few strides from there, the sumptuous “Arte Povera,” curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, is one of the largest exhibitions devoted to this key historical artistic movement, with almost 250 works from its thirteen main artists. Spreading into the entire space, its intense curation proposes a maximalist reinterpretation of Arte Povera, articulated around the idea of the baroque and accumulation, that evokes certain moments of Turin’s “Deposito d’Arte Presente” (Warehouse for Present-Day Art, ca. 1968), several views of which are reproduced in the catalogue. The result is a joyful re-reading that is more philosophical and phenomenological, if not esoteric, than political, far removed from its combative, Celantian dimension. In this way the exhibition emphasizes the tension between these two formal and conceptual poles that coexist within this historic movement [see also my extensive review, in Italian, in Flash Art Italia].

“Atomic Age,” a rich exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, stands out as one of the few current shows in Paris not to be influenced by sobriety. Its opulence is delightful, and it offers a vast collection of works. The show is articulated around the representation of an “atomic age” synonymous with both modernity as it was seen in the 1960s as well as destruction. Some pieces, particularly those from Japanese artists, are rarely seen in Europe: these include a set of para-photographic works by Kawani Hiroshi from 1964, on loan from Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art; a video by Motoharu Jonouchi (1964) featuring Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono; and Tetsumi Kudo’s large-scale installation Grafted Garden/Pollution-Cultivation-Nouvelle Écologie (1970/71). This piece, which anticipates much of Kudo’s later work, depicts a garden deformed by the use of nuclear power, in which plastic flowers, parts of a male mannequin stuck on rods, light bulbs, grids, and gloves are assembled on a bed of earth.

The exhibition also includes works by major artists like Sigmar Polke, Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, Bruce Conner, General Idea, Francis Bacon, and Jim Shaw, among others, offering a wealth of discoveries and rediscoveries.

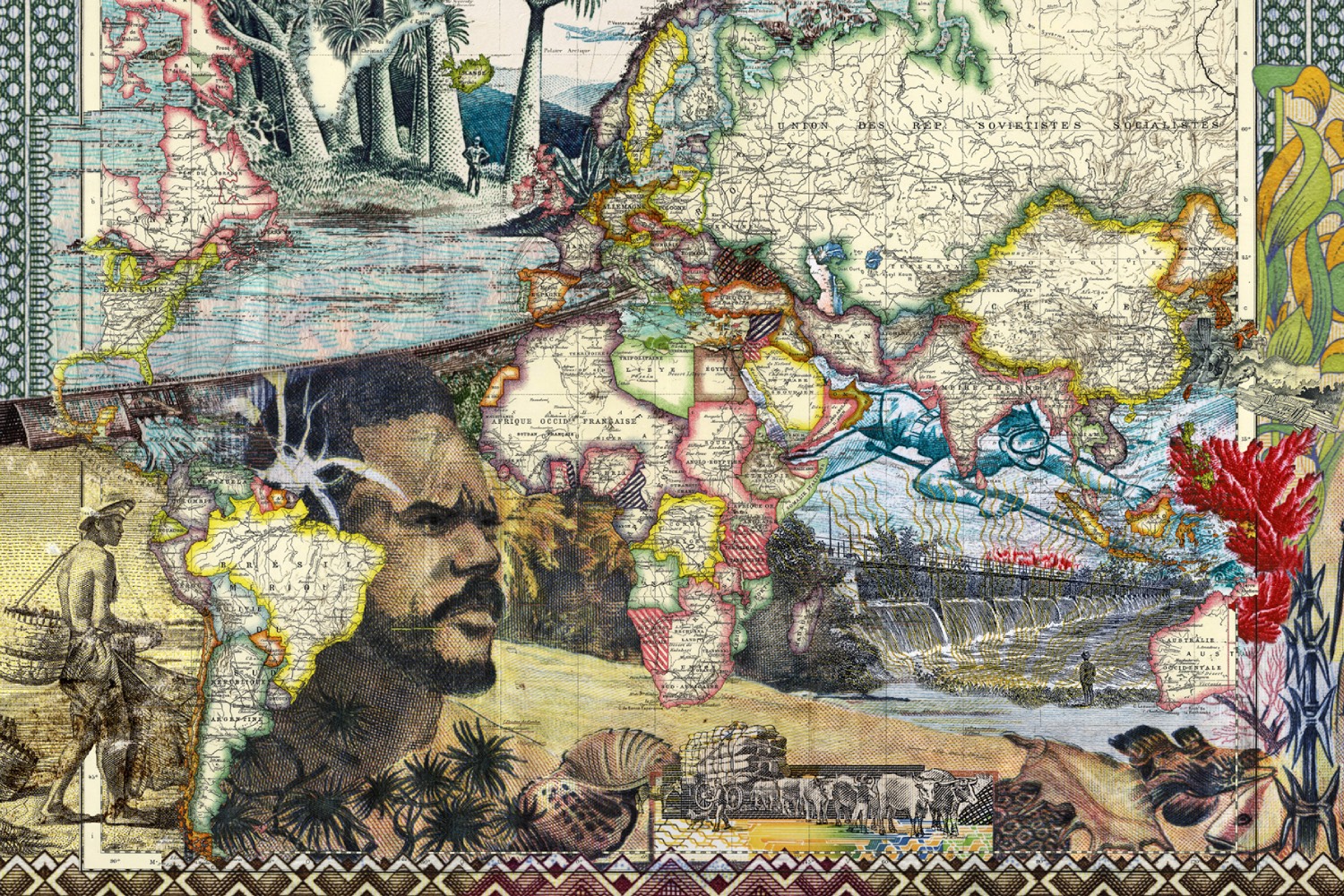

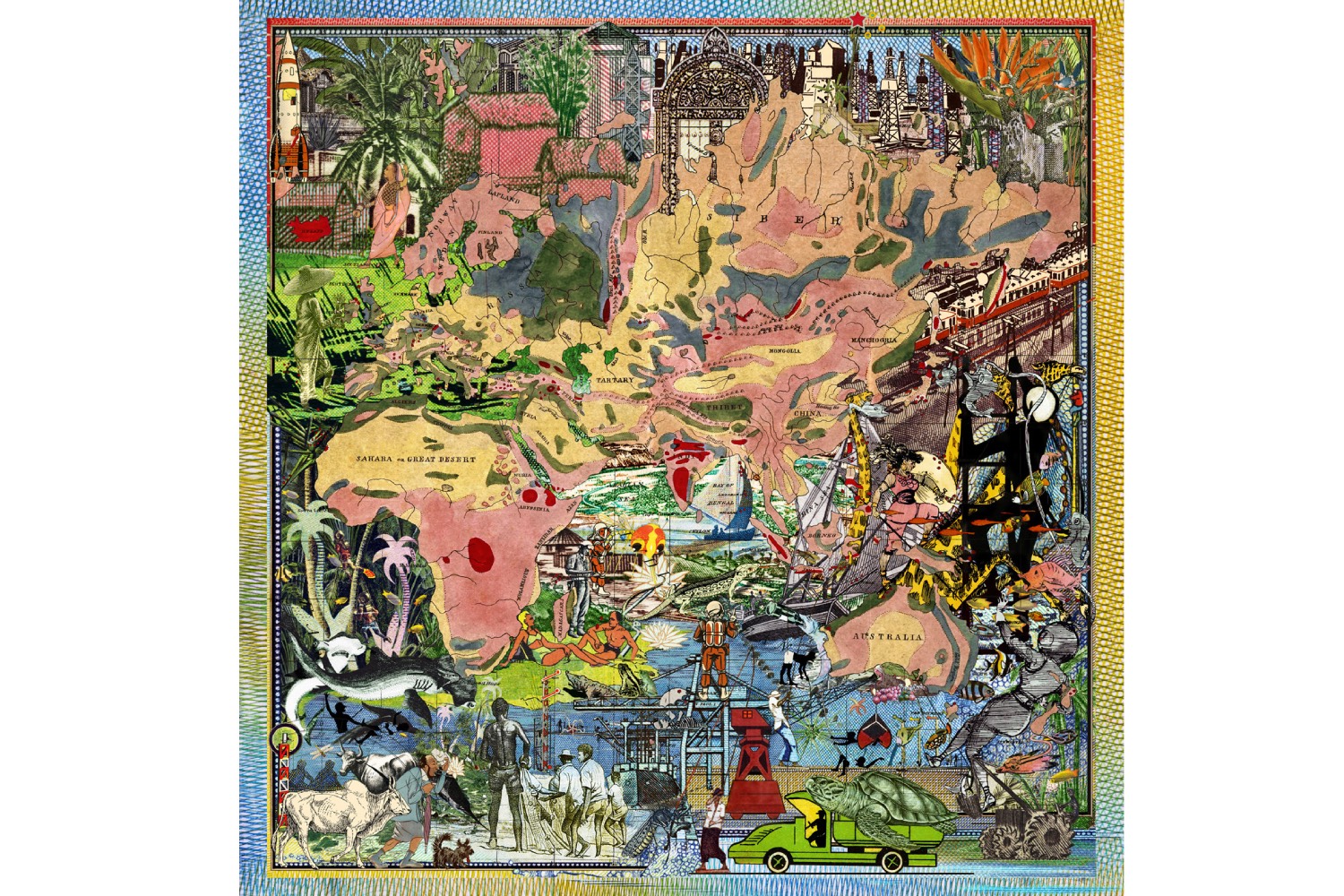

At Palais de Tokyo, the ethical and ecological sobriety of the first season of exhibitions entirely conceived under the directorship of Guillaume Désanges forms a highly homogeneous whole, placed under the sign of “invisible tremors” and “absent figures.”Stretching across the sixty-meter curve of the building’s main hall, a large digital collage by Malala Andrialavidrazana, forming a retrospective of her work, is curated by François Piron. This is followed by a brief exhibition by Barbara Chase-Riboud – one of the eight current shows dedicated to the artist in Paris. Here, it brings together a series of abstract black vertical bronzes with a memorial dimension from the “Standing Black Woman of Venice” series (1969–2020), along with the “White Drawings” series (1973–2023) that are works on paper embroidered with white threads.

The vibrant group show “Tituba, qui pour nous protéger?” — an allusion to the title of the novel Moi, Tituba, sorcière noire de Salem (1986) by the recently deceased Maryse Condé — presents a range of works by young female artists from the African and Caribbean diaspora, including Rhea Dillon, Abigail Lucien, and Inès di Folco Jemni.

Meanwhile “Praesentia,” a retrospective of Myriam Mihindou’s subtle works co-curated by Daria de Beauvais and Marie Cozette, features, alongside a large group of two-dimensional works, a series of installations and some videos that recreate performative works. The exhibition will later travel to the CRAC Sète.

This year, the 25th Fondation Pernod-Ricard prize was exceptionally awarded to all seven artists featured in the exhibition “All the Messages Are Emotional” (a work by each one will enter the Centre Pompidou collections). The first room shows works from Clémentine Adou’s “Boxes” series (2021–ongoing). These large cardboard boxes used to pack consumer products, then meticulously painted and varnished or covered with aluminum leaf by the artist, deliberately obtrude the space with their monumentality, resetting the visitor’s relationship to the pictorial work, that in turn becomes three-dimensional and penetrable or habitable. The Purple Chamber (2024), a large installation by Paul Maheke, who currently has a solo show at Galerie Sultana in Paris, superimposes transparent fabric, as an evanescent curtain, emblematic of his work, over spectral, surrealistic drawings, faced by luminous globes on the floor.

At Fondation Louis Vuitton, Tom Wesselmann’s exhibition situates his work within the context of the Pop and Dada movements.

Notable, too, is the compact yet meaningful exhibition dedicated to Corita Kent at the Collège des Bernardines, as well as the typically French “Compléments sous contrainte—Ou-X-po (Ouvroirs de créations potentielles)” at the Sorbonne, the exciting shows by Ingrid Luche (Air de Paris), Myriam Cahn (Jocelyn Wolff), and Pauline Bastard (22m48) at Komunuma — a major cluster of galleries that has been together for the past five years in Pantin, just outside Paris – and much more.

At the opposite end of the urban spectrum, the ongoing revitalization of the Matignon Saint Honoré district is still coming into focus. Galleria Continua opened a new venue designed by Jean Nouvel; Galerie Mitterrand pre-opened a 250-square-meter location, far from the confidential space initially envisaged; Sotheby’s moved into its spectacular new atrium space under the art deco glass roof of the former Galerie Bernheim-Jeune; and most of the galleries have formed an association.

One could mention many more of the shows on view in today’s bubbling Parisian artistic scene, such as museum-quality exhibitions in galleries featuring Arte Povera artists — such as Tornabuoni and Continua — Surrealist ones, throughout Saint-Germain des-Prés — or the more recent and contemporary ones, such as Bertrand Lamarche’s solo show (Galerie Jerome Poggi), which combines models of imaginary architectural structures with videos; Laura Gozlan’s exhibition “Liminalities” (Galerie Valeria Cetraro); and many more, exhausting the crazy visitor who plans to try to see nearly everything in this gargantuan program.

Anyway, as I then thought, the shift from the gigantism of 2022 to the sobriety of 2024 has been quite a ride, in keeping with the trend of ever-more-worrisome international news – particularly as I write this paragraph on Tuesday, November 5, 2024, at 8 p.m.