Erika Verzutti’s solo show “The Life of Sculpture” at LUMA Arles, curated during her residency from May to July 2024, is a compelling exploration of the life cycle of sculpture as both a material and conceptual identity. Her works, rooted in her Brazilian heritage and deeply engaged with texture and materiality, reflect an ongoing dialogue between sculpture, history, and the organic world. The residency provided Verzutti with an opportunity to produce a new body of work and develop an ambitious film project that explores the lives of sculptures once they are finished – the moment they become autonomous beings, capable of communicating beyond the artist’s original intentions.

The show itself is a dynamic mix of bronze and concrete sculptures, as well as three-dimensional wall works that embrace a colorful palette. Verzutti’s sculptures are layered with visual references to organic forms — fruits, eggs, body parts — creating a surreal world that toes the line between figuration and abstraction. These forms also reference a wide range of influences, from modern art to Brazilian architecture, often embedding playful nods that can verge on the erotic. In the show at LUMA, these organic forms are set against the backdrop of Verzutti’s characteristic use of newspaper, encapsulated in resin, which acts as both a material and conceptual boundary.

Notable pieces in the exhibition are Homeopatia and News (2024) and Crisis of Sculpture (2024), two horizontal sculptures resting on newspapers encased in resin, evoking a sense of suspended time. The use of resin creates a watery effect, as if the sculptures and the news they rest upon are submerged, muted by layers of transparent material. For the artist, newspapers carry both a personal and societal weight –– an element of everyday reality, frozen in a moment of time and distanced from its immediate content. As she explains, newspapers are often a source of anxiety, yet when caged, inside resin in this case, they become distant echoes, their muteness reflecting a form of protection or avoidance of the overwhelming flood of information.

Her relationship with newspaper is visceral. As she puts it, they are things we are “supposed to know” but often wish to escape. The resin casing, therefore, serves to isolate and mute, creating a barrier between the viewer and the world beyond, a symbol of Verzutti’s desire to distance herself from external noise. In the cemetery sculpture Cemetery of Starts (2024), newspapers reappear alongside other objects with personal significance that were otherwise rejected during the creative process. These “cemeteries” become a place of rest and reflection, a final home for failed or discarded attempts that nonetheless carry emotional or historical weight. The matches in one cemetery sculpture, for instance, were kept by the artist for years, despite their uselessness as functional objects. They, along with other relics, are given a new life in this funerary setting, symbolizing both the artist’s process of letting go and her reconnection with materials from the past.

One of the most poignant aspects of Verzutti’s work is her insistence on allowing materials to speak for themselves. Her approach is refreshingly non-conceptual. She doesn’t begin with an idea to communicate but instead lets the materiality of the work guide her. The time spent with these objects is critical –– without it, she asserts, “nothing happens.” There’s a certain intimacy in her process, a deep relationship between the artist and the object that unfolds over time, leading to spontaneous decisions and adjustments. In her studio, everything happens at its own pace; the sculptures emerge as they wish, with Verzutti guiding but never fully controlling the outcome.

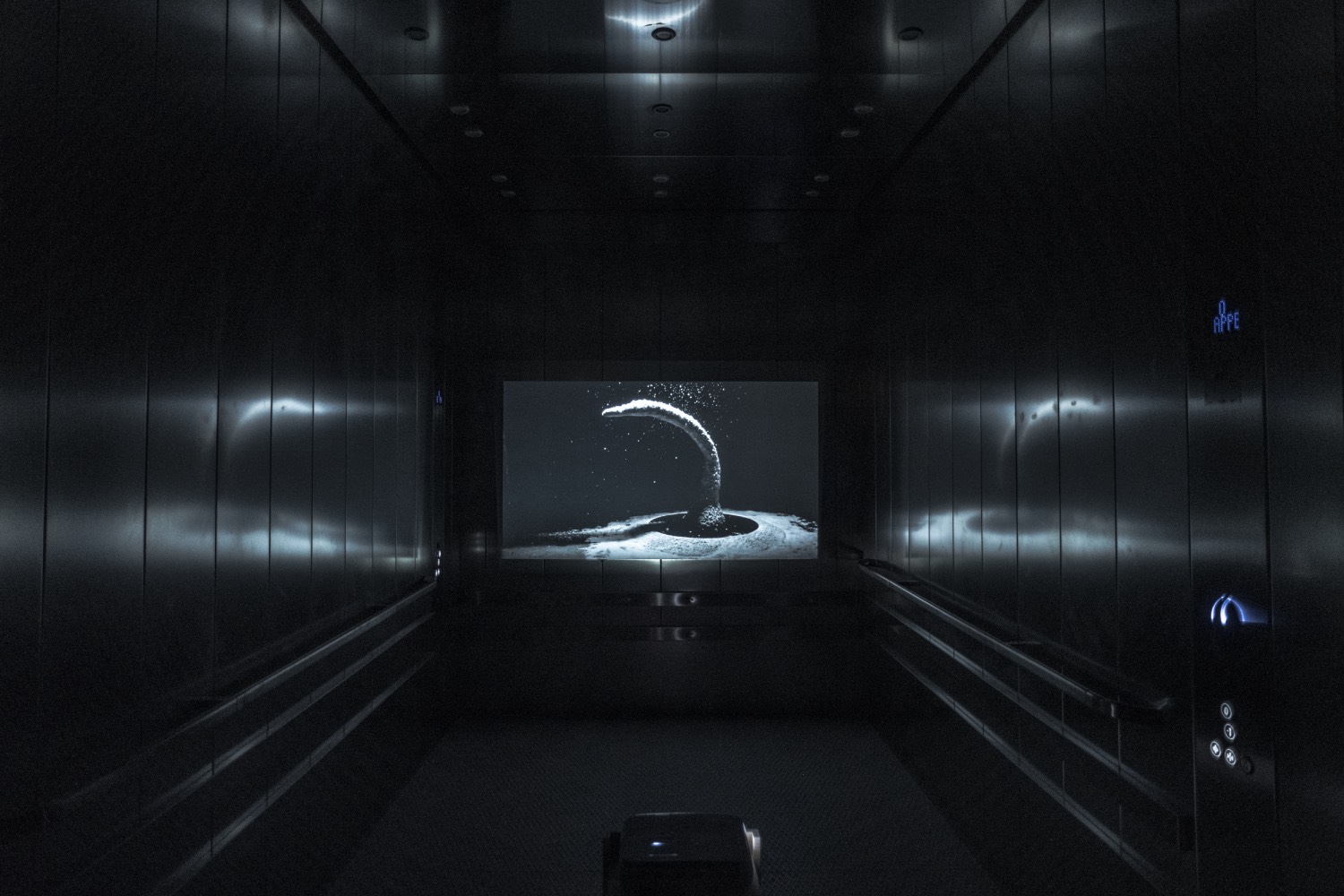

The show at LUMA embodies this process of emergence. The space resembles an artist’s studio –– a place where works in progress coexist with finished pieces, and where ideas flow freely, unbound by rigid definitions of completion. The sculptures exist in a state of becoming, and this resonates deeply with the overarching theme of her film project The Life of Sculptures (2016–24). Filmed in collaboration with Brazilian director Joana Luz, it explores the autonomy of sculptures, showing them as living entities, with desires, stories, and futures of their own. Verzutti wants to strip away the human element from the film, focusing solely on the sculptures and allowing them to occupy the narrative space fully.

In “The Life of Sculptures,” it becomes clear that, for Verzutti, sculpture is more than just a static object. It has its own life, its own presence, and its own way of interacting with the world. Each piece in the exhibition feels alive, imbued with an aura of time and care that transcends mere artistic creation. This interplay between the organic and the sculptural, the completed and the in-progress, forms a reflection on the nature of artistic process itself. Balancing playfulness and seriousness, Verzutti invites viewers into her world – one where materials live, speak, and evolve long after the artist’s hand has left them.